The battle is notable for several reasons. First, it was a complete and final victory, ending any threat from the Spanish naval forces involved. All major Spanish ships were destroyed or captured, without any significant damage occurring to the American Forces.

Secondly, technically no Americans lost their lives in the battle (two American deaths did indirectly occur which may be attributable to the battle), though the lives of many Spaniards were lost. The result is that Americans look at the victory as a "bloodless" battle, whereas the Spanish obviously do not.

Thirdly, the American attack was very daring and dangerous, based on what the Americans knew at the time, but not as risky when looked at in hindsight. Many world powers, who were not aware of the American naval build-up over the past decade and a half, considered the United States Asiatic Squadron to be little or no threat to the Spanish naval forces. The Americans also over-rated the Spanish navy's ability and determination to fight, and many authorities considered the fleet to be sailing into a veritable deathtrap. In addition to the naval forces, many Spanish gun batteries existed in the fortifications around Manila Bay. These guns alone should have been enough armament to destroy the American squadron.

Lastly, the American Asiatic Squadron was not sufficiently supplied with ammunition for wartime service and the nearest site for resupply was California, seven thousand miles away!

By far, the most notable aspect of the battle was that, as a result of this battle, the United States became a recognized world power overnight. The U.S. Navy had been a subject of derision internationally for years. The United States had begun to change that with the advent of its new steel navy, but, in a time when a country's military was rated according to the strength of its navy, this was the first time that the ability of both the U.S. warships and their well-trained crews were shown to be an important world force.

The main objectives of the Spaniards were to defend the Philippine outpost of the Spanish Empire against the American forces, save the honor of the nation by fighting an honorable fight, and allow as many of its crewmen to survive as possible. The thought of actually defeating the American Asiatic Squadron with the Spanish forces available was not considered a realistic objective.

It consisted of the USS OLYMPIA, a cruiser; USS BOSTON, a small cruiser; USS PETREL, a gunboat; and the USS MONOCACY, a paddle wheel steamer. This fleet was not formidable. The MONOCACY was only fit for river service. The largest vessel, the OLYMPIA, was fairly new, but was not "state of the art" and could not compete in firepower with the newer U.S. Navy battleships, such as the OREGON. Dewey discovered another very serious concern - his squadron did not have even a peacetime allotment of ammunition, and war could be approaching.

The major Spanish landholding in the Pacific was the Philippine Islands, and it was here where Dewey could expect to find the Spanish fleet. A search for information revealed that no U.S. naval vessels had visited the islands in twenty-two years, so there were no modern official intelligence reports available! Still, commerce did continue and this was one major source of information as to the state of the Philippines defenses. Another source of information in Manila was U.S. Consul Williams, who stayed on in Manila until he last moment, though subject to death threats. Dewey, while in Hong Kong had Lt. Upham of the OLYMPIA dress in civilian clothes and spook around vessels arriving from the Philippines, talking to their crews, etc. Upham was able to give Dewey valuable and up-to-date intelligence based on the interviews he conducted, including that the Spanish were claiming to have mined the entrance to the Bay. Lastly, Dewey had an American businessman acquaintance who periodically visited the Philippines when special information was needed by Dewey on a certain intelligence items. This man's identity has been lost to history. In short, Dewey was able to gain fairly accurate intelligence on conditions as they existed in the Philippines.

Dewey immediately began acting to rectify the problems of lack of ammunition as he had the lack of intelligence information. His ammunition, a dangerous cargo which commercial shipping companies would not haul, was to be shipped via the USS CHARLESTON. This vessel, however, was undergoing repairs which would not be completed for six months. The commodore found that the USS CONCORD was being fitted out to be sent to the Asiatic Squadron. He obtained orders for this vessel to carry a portion of the needed ammunition. He reinforced the urgency of this order by personally visiting the navy yard and convincing the authorities to pack as much ammunition as possible aboard the vessel. He explained that additional space could be saved if the vessel stopped at Honolulu for resupply rather than carrying enough stores for shipboard use for the entire journey. Also, he recommended purchasing some supplies in Japan, rather than taking up space with them for the long voyage. In this way, he had about half of the available ammunition sent to the Asiatic Squadron. The remainder was sent to Honolulu via the sloop USS MOHICAN and then transferred to the USS BALTIMORE. The BALTIMORE was being sent at the last hour to reinforce Dewey. The ammunition from this vessel was finally distributed to the other vessels only the night before the squadron steamed out of Mirs Bay for the Philippines! In spite of these efforts, at the Battle of Manila Bay, the squadron's magazines were only sixty per cent filled.

Dewey's force continued to grow. The USS RALEIGH was sent the squadron, and the U.S. Revenue Cutter McCULLOCH, which happened to be in the area, was ordered to join Dewey also. Lastly, the squadron gained the NANSHAN and the ZAFIRO as support vessels which were merchant vessels purchased outright. These vessels were maintained officially as merchant vessels and cleared for trade through Guam. This move would allow Dewey a way to purchase supplies after war broke out and neutrality laws would forbid the selling of wartime allotments of supplies to vessels of war.

As the tension between the United States and Spain grew, Dewey prepared his fleet. The men were drilled. The ships were mechanically reviewed to get them in best working condition possible. Dewey's planning and efficiency is well demonstrated by the late arrival of the BALTIMORE. Within forty-eight hours, she was placed in an awaiting drydock, her bottom cleaned of the speed-stealing barnacles, and she was completely repainted in wartime gray, just in time to join in the expedition to Manila.

With the declaration of war, Dewey moved his ships out of neutral Hong Kong to Mirs Bay, about 30 miles away. While at Mirs Bay, the squadron received a small gift. Reputedly, one of the lookouts spotted something floating on the water surface a few miles away. It was investigated and found to be several lighters of coal. Dewey put the coal to use. Later it was found that the coal was a gift from one of the Hong Kong merchants for the American fleet. From Mirs Bay, the squadron left for the Philippines and destiny. Dewey, however makes no note of this event in his report.

The Spanish were preparing for action too. They had attempted to fortify their position by taking guns from their vessels and placing them in positions at critical locations along the shore. The VELASCO was being overhauled, her boilers and steering gear removed, so her guns were considered to be more useful in the fortifications. Some of the GENERAL LEZO's battery and the port-side guns of the DON ANTONIO DE ULLOA were also removed. Orders were given for the fortification of Subic Bay, and the entrances to both it and Manila Bay were to be mined. Several vessels were sunk in the eastern entrance to Subic Bay to block passage by that route.

On April 25, 1898, Admiral Montojo took his squadron, consisting of the REINA CRISTINA, DON JUAN DE AUSTRIA, ISLA DE CUBA, ISLA DE LUZON, CASTILLA, MARQUES DEL DUERO from Manila Bay and headed for Subic Bay. The CASTILLA, already unable to maneuver on her own, was leaking badly through her propeller bearings. The leak was stopped by using cement, which rendered her engines completely useless. Upon arriving, he found that the four 15 cm (5.9') guns which were to have been installed in a fortified position were still lying on the beach. The mines which had been laid were of doubtful condition and could not be relied upon.

Both Dewey and Montojo recognized that the best location for the defending squadron was Subic Bay from a tactical standpoint. Even after Montojo arrived in Subic Bay, he hoped that there was still time to fortify the necessary positions. However, on April 28, Montojo learned that Dewey's squadron was on it way to the Philippines, and that the Americans knew that Subic Bay was defenseless. Faced with no time to fortify, and knowing that if his ships were lost - something Montojo considered a strong possibility - the crew would drown in the deep waters of Subic Bay. Montojo ordered the squadron back to Manila Bay.

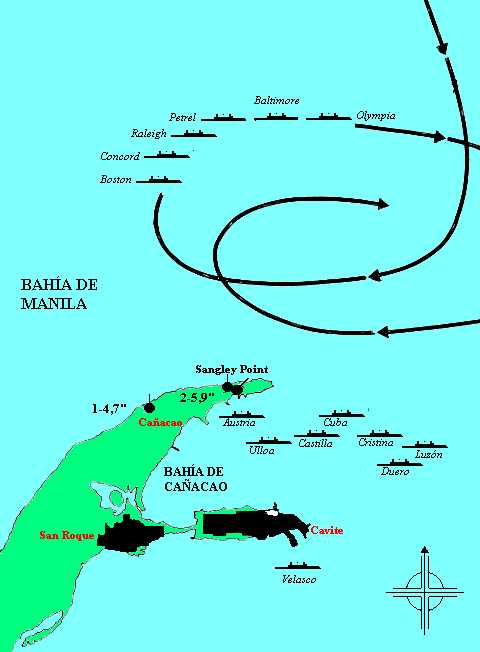

The Spanish admiral decided that returning the squadron to the anchorage at Manila, which was surrounded by many batteries and fortifications, would be unwise, since this would invite the destruction of the city itself by the guns of the enemy's squadron. Manila was home to the families of his crew and many other non-combatants. Instead, he opted for the shallow waters off Cavite's Sangley Point. Here he could combine the gunfire from his vessels with that of the batteries of Sangley Point and Ulloa. Also, in this location, if his ships went down, they would settle into the bottom of the Bay while still allowing major portions of the vessels to remain above water. His men would be able to get to shore and rescue themselves. Montojo had lighters loaded with sand brought over to be placed in front of the CASTILLA to protect the wooden vessel. Preparation continued as the sound of gunfire at the entrance to Manila Bay announced the arrival of Dewey's Asiatic Squadron.

Aboard the American vessels, last minute preparations continued. The ships' crews continued throwing anything made of wood overboard, since the danger from splintering and fire was very serious. On board the McCULLOCH, virtually all of the mess tables were tossed into the water, leaving the crew eating off the deck for a long time after the battle. The same was true of almost all of the ships except for the OLYMPIA. Dewey, wisely or unwisely, left much of the wood intact, simply covering it with canvas and splinter netting. Many of the items to which the OLYMPIA's crew had direct access, were, however, thrown overboard. Sand was sprinkled on the decks for traction in battle.

There were two major channels which led into Manila Bay - Boca Chica and Boca Grande. Boca Chica was the main shipping route, however it was narrower and more heavily defended by shore batteries than Boca Grande. Boca Grande which, according to recent reports (suspected to be part of a Spanish disinformation campaign), was said to be dangerously rocky. Dewey believed the water to be deep in this area. Reports were also heard that this entrance to Manila Bay was mined. Dewey also discounted the rumors of mines stating the the report was probably untrue, and if it was true, that the Spanish did not have the capability to mine in deep water. Also, the Commodore believed that the mines, if placed, would deteriorate rapidly in the trpoical waters. Later, based on captured Spanish officers and records, indications were that Dewey was wrong in that the channel was mined. The mines, however, must have deteriorated, as Dewey's vessels, as well as subsequent visitors, reported no damage from mines.

The Asiatic Squadron steamed into Boca Grande at about 11:00

P.M. The men were at their guns, and the situation was very tense. All

lights were out, except for one veiled stern light on each ship, to enable

the vessels to follow one another. The men knew of the rumors of mines,

of the reported shoals, and of Spanish shore batteries. They expected to

meet a squadron ready for battle. They also knew that they were low on

ammunition and seven thousand miles from resupply. What they did not know

was the Dewey had also underestimated the number of Spanish vessels present.

The vessels, with OLYMPIA in the lead and NANSHAN and ZAFIRO bringing up the rear, steamed past the little island of El Fraile. The island had a battery of guns taken from the GENERAL LEZO. When almost all of the American vessels were past El Fraile, flames shot from the McCULLOCH's funnel as some soot caught fire briefly. She had been supplied with Australian coal which did not burn as cleanly as the Welsh coal provided for the other vessels in the Squadron. McCULLOCH had experienced periodic flare-ups as the coal soot burned in her funnel. The battery on the island saw the most recent flame and opened up, sending a shot between the RALEIGH and the PETREL. The BOSTON, McCULLOCH, RALEIGH and CONCORD returned fire, and the battery fell silent. It has never been explained why the El Fraile battery did not put up more of a fight or fire earlier. The American vessels were plainly visible in spite of the darkness. Some claimed that there were not enough men present to man the fort's guns.

The gunfire from the El Fraile skirmish was heard in Manila. Montojo knew what it meant. At 2:00 a.m., he received a telegram confirming that the Americans had passed El Fraile. He notified army commanders, ordered all artillery loaded, and sent all soldiers and sailors to their battle stations. The Spanish waited. They had already removed masts, yards and boats to avoid splintering from the projectiles of the American guns, a major source of injury.

The Asiatic Squadron set off across Manila Bay with a goal of arriving at Manila, where Dewey expected to find the Spanish Fleet, at dawn. To meet this schedule, the squadron slowed to four knots. The men were given a chance to catch some sleep at their guns, if the tension of the situation would allow it. The crews on board the vessel saw flares, beacons, rocket and fires dot the shoreline as their movements were tracked. The Commodore sent signals to his squadron using his ardois lights....secrecy was no longer a possibility.

At 4:00 A.M., Montojo signaled his forces to prepare for action. At this same moment, coffee was being served to the men of the American squadron. At 4:45 A.M., the crew of the DON JUAN DE AUSTRIA spotted the American Squadron. Sending the NANSHAN, ZAFIRO under protection of the McCULLOCH to a safer location in the bay, the Americans headed directly for Manila, where they expected the Spanish warships to be. This was a logical location since the strong shore batteries would greatly augment the firepower of the Spanish vessels. Not seeing anything but merchant vessels in the anchorage, the American vessels turned toward Cavite. At 5:05 A.M., the guns of the three of the Manila batteries opened fire. Only the BOSTON and CONCORD replied, since the limited ammunition was to be used against the Spanish fleet and not the forts. Montojo had the REINA CRISTINA slip its cables and begin to move. To clear his path, he ordered several mines, which could have been a hazard to his ships, blown. Their explosions were spotted by the American crewmen. Dewey misinterpreted the reason for the reason for the explosion of the mines, commenting "Evidently the Spaniards are already rattled." The Squadron moved ahead in battle order - OLYMPIA, followed by BALTIMORE, RALEIGH, PETREL, CONCORD, and BOSTON at two hundred yard intervals.

The

Americans finally spotted the Spanish vessels in their Cavite anchorage

between Sangley Point and Las Pinas. At 5:15 a.m. the guns of the Cavite

fortifications and the Spanish fleet opened fire. Dewey had his ships hold

their fire until 5:40 A.M. Then, standing on the vessel's open bridge,

he quietly told the OLYMPIA's captain, "You may fire when ready, Gridley."

The OLYMPIA's forward eight inch turret fired. The other ships of the column

followed suit. The Americans kept the Spanish vessels off their port bow

during their initial attack, since this allowed the maximum number of guns

on each ship to fire.

Though it was not obvious to the Americans, who noted that the damage to the Spanish vessels must not have been too great since the fire from their vessels did not slacken, destruction came quickly to the Spanish fleet. Montojo commented that the first three ships seemed to direct their fire mainly on his flagship, REINA CRISTINA. Soon a shot hit her forecastle, put the crews of four rapid fire guns out of action, shattering the mast, and injuring the helmsman, who had to be replaced. Another shell set flew into the vessel's orlop deck, starting a fire which was rapidly put under control.

The American ships came in as close as they thought the depth of the water would allow, first passing the Spanish position from west to east, and then countermarching east to west. Five passes were made along the two and a half mile course by the Asiatic Squadron at a speed of six to eight knots.

Suddenly, around 7:30 A.M., Commodore Dewey had a rude awakening.

Captain

Gridley relayed a report that the vessel was down to only fifteen rounds

of ammunition for each five inch gun. The five inch guns were the OLYMPIA's

most effective gun, since they could fire much more quickly than the 8"

turret guns. Fifteen rounds of ammunition could, under rapid fire condition,

be expended in two minutes! Realizing that running out of ammunition could

spell the end of his squadron, and not being able to determine the extent

of the damage to the Spanish vessels amidst the smoke of battle, Dewey

decided to withdraw to redistribute ammunition and assess the entire situation.

To avoid having the Spanish realize his plight and give them additional

reason to hold out longer, the commodore had the signal sent to his squadron

that the ships were breaking off to allow the men time for breakfast. The

men greeted this with consternation. It was later noted in the American

press as an example of the nonchalance the Americans exhibited in the battle

by stopping in the middle for a bite to eat, while still within range of

the enemy's guns in their fortifications.

Very quickly, though, it was found that the report was in error. Instead, only fifteen rounds per five inch gun had been expended. This indicated that the men were showing unusual restraint by firing only after taking time to aim, and trying to make every shot count. A call went out for the commanders of the ships of the squadron to report their damage, casualties and ammunition status. The men, somewhat confused by this turn of events, ate and rested. The engine room crewscame up on deck to get away from the stifling heat below decks and survey the carnage which was becoming evident from the direction of the Spanish fleet.

During the morning's battle, twice the OLYMPIA believed it was under attack from small torpedo boats. One of these it sunk, the other was run aground. Torpedoes were greatly feared weapons, because, with them a small vessel could conceivably sink a large vessel. However, the Spanish reports make no report of these attacks, and it now appears that these vessels, military or civilian, were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time and were not torpedo boats.

Twice, near the end of the battle's morning phase, Spanish men-of-war had made attempts to close on the American squadron. First, the DON JUAN DE AUSTRIA attempted to charge the OLYMPIA. The heavy gunfire of the fleet had forced her to abandon the effort. Shortly after this action, the Spanish Flagship, REINA CRISTINA also tried to close on the OLYMPIA, possibly to try to ram her. While making this attempt that the REINA CRISTINA's steering gear was detroyed as she again became the focus of the galling fire of the American squadron.

Unbeknownst to the Americans, the Spanish fleet was already defeated when Dewey "broke for breakfast." Very close to the end of the morning's phase of the battle, the REINA CRISTINA was hit by a number of projectiles. In addition to the shot that destroyed her steering gear, another shot, sadly, hit her in the area that was being used as a hospital, killing many already wounded men. One shot fatally hit a stern ammunition handling room, hampering further steering attempts, and resulting in the flooding of the nearby magazines. Fire broke out elsewhere while the broadside guns continued firing, though only one gunner and one seaman remained unhurt and able to work the guns. Half of her crew was out of action, and seven officers were lost. Montojo ordered the vessel scuttled, and tried to save his men.

The Spanish admiral transferred his flag to the ISLA DE CUBA. Now, in the lull of the American "breakfast break" he could survey the damage. The DON ANTONIO DE ULLOA had been sunk, and half of her crew and her commander were put out of action. Some of her remaining crew may have stayed aboard refusing to abandon her. The CASTILLA had been set afire in the action and riddled with shot. She was abandoned and sunk, with a loss of 23 men killed and 80 wounded. The ISLA DE LUZON had three guns dismounted, while the MARQUES DEL DUERO was "sadly cut up."

Montojo ordered the remainder of the fleet, those that could still maneuver, to retreat back into Bacoor Bay, fight on as long as possible, and then scuttle the ships before surrendering.

Dewey's guncrews had found their marks, in spite of actually hitting their targets only about one to two percent of the time. This hit rate was low, but not unusual in the period. . In fact, it was higher than the American hit rate at the later naval Battle of Santiago, a fact attributable to the Spanish vessels being generally stationary targetsThe Spanish, of course, hit their targets much less than the Americans.

Meanwhile, the reports from Dewey's subordinates began to arrive aboard the OLYMPIA. The information was shocking. In spite of what seemed to be a strong Spanish barrage, there were no lives lost aboard the American vessels. Two officers and seven men were injured, most only slightly. Eight of the injuries were from a single hit on the BALTIMORE, with the remaining injury occurring aboard the BOSTON.

By 11:16 A.M., the lull was over. The Asiatic Squadron went back

on the attack. It was now evident to the Americans that the Spanish fleet

was ablaze and sinking. The BALTIMORE led the attack the second time, switching

places in line with the flagship. She had been sent to intercept a vessel

which turned out to be a merchant vessel, and was closer in to the enemy.

As the remainder of the fleet was considerably behind her, the BALTIMORE

requested and obtained permission to shell the Canacao Battery and Fort

Sangley. The spirited exchange went on for ten minutes, with the Canacao

and then Fort Sangley being silenced.

As the American ships got within range, some reports indicate that the crew that remained aboard the DON ANTONIO DE ULLOA, already a wreck, may have opened fire. Whether this was indeed fire or merely the "cooking off" of ammunition is not clear. However, she was answered by the fleet, and savagely raked. The Spanish crew, if they were still on board, won the respect of the Americans for their bravery, and must have finally decided to abandon ship.

The Asiatic Squadron received orders from the flagship to break ranks. The CONCORD was ordered to destroy the beached ISLA DE MINDANAO, mail steamer thought by the Americans to be a transport. The PETREL, because of her shallow draft, was ordered to perform the risky duty of proceeding into the shallow waters of Cavite to capture or fire any vessels there. After a few shots from her six inch guns, the forces on Cavite itself surrendered. The PETREL also captured the transport MANILA and several smaller vessels.

The American losses were minor, consisting of nine men injured. In addition, Captain Gridley of the OLYMPIA, already gravely ill, would pass away about a month after the battle, his condition worsened by his hours spent in the hot conning tower aboard OLYMPIA that morning. Chief Engineer Randall of the McCULLOCH had passed away from a heart attack as the squadron entered Manila Bay, but may be considered a casualty of the battle also, since his conditon may have been the result of the tension of the moment and the heat of the engine rooms.

The Spanish losses were much higher. Admiral Montojo reported a loss of 381 men killed and wounded as a result of the battle.

However, the Battle was over. The Spanish vessels had been destroyed. Though the guns of the fortifications around Manila still had the power to sink the American squadron, the threat of a return bombardment of the city kept the guns silent. That evening, the USFS OLYMPIA Brass Band serenaded the crowds of people teeming along the Manila waterfront with a selection of music including many Spanish numbers, punctuated by continued explosions of ammunition aboard the still-burning Spanish vessels. It was an strange end to a strange day.

OLYMPIA - (5870 tons, four 8" guns, ten

5" guns, 21 secondary rapid fire guns, six torpedo tubes, 381 men)

BALTIMORE - (4413 tons, four 8" guns,

six 6" guns, 8 secondary rapid fire guns, 328 men)

RALEIGH - (3213 tons, one 6" gun, two

5" guns, 12 secondary rapid fire guns, 2 torpedoes, 252 men)

BOSTON - (3000 tons, two 8" guns, six 6"

guns, 6 secondary rapid fire guns, 230 men)

CONCORD - (1710 tons, six 6" guns, 6 secondary

rapid fire guns, 155 men)

PETREL - (892 tons, four 6" guns, 3secondary

rapid fire guns, 110 men)

McCULLOCH - (exchanged fire with Battle

on El Fraile Island, otherwise not engaged, 1280 tons, 4 secondary rapid

fire guns, 68 men)

NANSHAN - (not engaged, unarmed)

ZAFIRO - (not engaged, unarmed)

The Spanish order of battle was as follows:

REINA CRISTINA - (3520 tons, six

6.2" guns , 13 secondary rapid fire guns, 5 torpedo tubes, 352 men)

CASTILLA - (3260 tons, four 5" guns,

two 4.7" guns, 14 secondary rapid fire guns, 2 torpedo tubes, 349 men)

ISLA DE CUBA - (1045 tons, four 4.7"

guns, 4 secondary rapid fire guns, 2 torpedo tubes, 156 men)

ISLA DE LUZON - (1045 tons, four 4.7"

guns, 4 secondary rapid fire guns, 2 torpedo tubes, 156 men)

DON ANTONIO DE ULLOA - (1160 tons,

four 4.7" guns, 6 secondary rapid fire guns, 159 men, one of her guns were

removed to Sangley Point)

DON JUAN DE AUSTRIA - (1159 tons,

four 4.7" guns, 8 secondary rapid fire guns, 2 torpedo tubes, 179 men)

MARQUES DEL DUERO - (500 tons,

one 6.2 inch gun, two 4.7" guns, 96 men)

GENERAL LEZO (not engaged, 520 tons, two 4.7" guns which were apparently

removed to El Fraile Island, 2 secondary rapid fire guns, 1 torpedo tube,

115 men)

VELASCO (not engaged, 1152 tons, three 5.9" guns which were apparently

removed to Caballo Island, 4 secondary rapid fire guns, 145 men)

EL CANO (not engaged, 560 tons, three 4.7"

guns, three secondary rapid fire guns, 1 torpedo tube, 115 men) In fact,

though the Americans reported this vessel as being EL CANO, EL CANO was

not present. This was probably EL COREO.

ARGOS (not engaged,

508 tons, one 3.5 " gun, 87 men)

MANILA (transport, not engaged, 1900 tons, 2 secondary rapid fire

guns, 77 men)

In addition, the Spanish had approximately 20 additional small gunboats operating the Philippines, but none of these vessels were engaged (QUIROS, VILLALOBOS, MANITENO, MARIVELES,MINDORO, PANAY, ALBAY,CALAMIANES, LEYTE, ARAYAT, BALUSAN, CALLAO, PAMPANGA, PARAGUA, SAMAR, BASCO, GARDOQUI, OTALORA, BARCELO, URDANETA, CEBU, GEN. ALAVA).

Captain Charles V. Gridley of the OLYMPIA - Gridley was already in poor health at the time of the battle. He could have been relieved of duty, but asked to be allowed to stay on. The stress of the battle and the excessive heat in his battle station in the OLYMPIA's conning tower (an armored steel cylinder with a slit in it to view the action outside) were too much for him. After the battle he was sent home. Gridley left aboard the ZAFIRO, escorted by the CONCORD. He died on board the S.S. COPTIC in Kobe, Japan on June 5, 1898, on his way home. Scarcely a month had passed since the battle.

Chief Engineer Randall of the McCULLOCH - Randall died of a heart attack as the vessels passed El Fraile Island while heading into battle, probably a result of the combination of the stress of the moment, and the intense heat in the vessel's engine room.

Below is the official list of injuries to the American forces at the Battle of Manila Bay.

U.S.S. BALTIMORE

Case No. 1 - Lacerated wound of upper lip by fragment of rotating band. Also wounds of right foot, in one of which there was a fracture of the fifth metatarsal bone extending into general synovial sac. Patient discharged to duty, entirely recovered, June 10. On the list forty days.

Case No. 2 - Lacerated wound (1 3/4 inches long) just below sternoclavicular joint. Healed by first intention. Discharged to duty May 7. On the list six days.

Case No. 3 - Compound fracture of the left leg in upper third from a fall while carrying an 8-inch shell, the point entering the inner side of leg and splintering inner border of tibia. Discharged to duty, entirely recovered, June 7. On the list thirty-seven days.

Case No. 4 - Contusion and concussion. Was knocked down by the windage of a 4.7-inch shell. Face badly bruised, and unconscious for one-half hour. Discharged to duty May 7. On sick list six days.

Case No. 5 - Wound of left leg from splinter. Not admitted to sick list.

Case No. 6 - Wound of left forearm. Contusion of left sternomastoid and rupture of left tympanic membrane. Not admitted to sick list.

Case No. 7 - Wound of right foot and abrasion of face from splinters. Not admitted to sick list.

Case No. 8 - Contusion over sternum and abrasion side of face. Not admitted to sick list.

U.S.S. BOSTON

Case No. 1 - Punctured wound of right cheek from flying splinter.

Not admitted to sick list.

Clerk of Joint Committee on Printing, The Abridgement of the Message from the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1899, Vol II, p. 1292.

The Cyclorama Company, Battle of Manila. (Philadelphia, 1899)

Dewey, George, Autobiography of George Dewey (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987, originally published in 1913 by Charles Scribner's Sons, New York) ISBN 0-87021-028-9.

Ellicott, John M., Lt., U.S.N.; "Effect of Gun-Fire, Battle of Manila Bay, May 1, 1898," Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute, Vol. #90, No.2, 1899.

Ellicott, John M., Lt., U.S.N.; "The Naval Battle of Manila", Proceedings of the U.S. Naval Institute, Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute, Vol. #95, No.3, 1900.

Healy, Laurin Hall, and Luis Kutner, The Admiral. (Chicago: Ziff Davis Publishing Co., 1944).

Jeffers, H. Paul, Colonel Roosevelt: Theodore Roosevelt Goes to War, 1897-1898. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996).

McSherry, Jack L., CQM, Ret'd., Things We Remember, Printed privately, 1966.

Millis, Walter, The Martial Spirit. (Cambridge: The Riverside Press, 1931).

Poncet, Jose, "The Use of Mines by the Spanish Navy, The Spanish American War Centennial Website (http://www.spanam.simplenet.com/Spanishmines.htm)

Sargent, Commander Nathan, U.S.N.; Admiral Dewey and the Manila Campaign. (Washington D.C.: Naval Historical Foundation, 1947).

Spector, Ronald, Admiral of the New Empire : the Life and Career of George Dewey. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974).

Young, L. S.; The Cruise Book of the U.S. Flagship OLYMPIA, 1895-1899.