By all accounts, young Dewey was a mischievous, high-spirited boy. In 1852, when George was fifteen, his father enrolled him in Norwich University, a military school on the Connecticut River across from Hanover, New Hampshire. He remained there two years, adding greatly to his reputation as a practical jokester. In 1854, received an appointment to the Naval Academy at Annapolis. The conventional four-year course had just been introduced in 1851 and the cadet corps was quite small, averaging about one hundred "Acting Midshipmen". Normally only about half the class, and sometimes considerably less than half, remained to receive their commissions at the end of four years. In George's class, only fifteen of the sixty men who entered as "plebes" remained to graduate. Dewey must have felt considerable pleasure and relief when, on June 18, 1858, he and his fourteen remaining classmates received their diplomas and their commissions. Through considerable application and effort Dewey had risen to fifth in his class, an achievement he attributed to his talent for mathematics and languages.

Following graduation, George was ordered to report immediately to the USS WABASH, a new steam frigate which was to be flagship of the Mediterranean Squadron. The WABASH left Hampton Roads on July 22, 1858, and returned to Brooklyn Navy Yard seventeen months later. Her cruise was quite unremarkable, but in the course of it, George developed an affection for the Mediterranean and its ports. After two more short cruises, Dewey returned to the Academy in January, 1861, to sit for his Lieutenant's examination. He passed out third in his class and received his commission in April, 1861. He was on leave in Montpelier when word of the surrender of Fort Sumter reached Vermont. A few days later, he was on his way to war.

The ship in which Dewey was to serve for the next two years was the old steam frigate MISSISSIPPI, a side-wheel paddler. Dewey joined the ship at Boston on May 10, 1861, and a few days later she was on her way south to join the Union blockade in the Gulf of Mexico. For several weeks after her arrival, MISSISSIPPI remained at Key West, Florida as temporary flagship of the blockading squadron, until she was relieved by the frigate COLORADO. In July, she took up station off Mobile Bay and later off the Mississippi River delta as a rather ineffective addition to the blockade squadron. In early 1862 at only twenty-five years of age, Dewey became the executive officer of the MISSISSIPPI. The vessel participated in the Battle of New Orleans on April 24-25, 1862.

For Dewey, the months after the capture of New Orleans were an anticlimax, the MISSISSIPPI was anchored off the city as a guard ship. In the spring of 1863, she was ordered up the Mississippi River to join Admiral David Farragut below Port Hudson, Louisiana. During the Battle of Port Hudson on the night of March 14, the MISSISSIPPI ran onto a mud bank, where she caught fire and was abandoned. After a few weeks ashore in New Orleans, Dewey was made executive officer of the MONONGAHELA, which was now serving as Admiral Farragut's flagship. It was aboard this vessel, in July, 1863, that he had the closest call of his career. A Confederate shell exploded on the ship's quarter deck killing the captain and four other officers but leaving Dewey unscathed. The end of the war found him a Lieutenant Commander, serving as executive officer of the sloop-of-war KEARSARGE on the European Station. At twenty-eight, he had served as executive officer of no less than six ships and participated in four major campaigns, as well as numerous spells of patrol and blockade duty. While stationed in Portsmouth, New Hampshire George had met Susan Boardman Goodwin, the daughter of the Governor, whom he married on October 27, 1867.

After a brief leave, Dewey took his bride to Annapolis, where he had been assigned as an instructor and officer-in-charge of fourth classmen. Three years later he was detached from the Academy and ordered to take command of the third-class sloop-of-war NARRAGANSETT. Dewey took over the ship at Portsmouth and brought her into New York Navy Yard for extensive repairs. NARRAGANSETT remained at her moorings for the next three months while her Captain vainly awaited orders to sail. Finally, in January, 1871, Dewey was ordered to take command of the store ship SUPPLY, which the Navy had provided to carry food and medicine donated by Americans to help French victims of the Franco-Prussian War. SUPPLY was a sailing ship, old and slow. By the timed she reached Cherbourg, the French had surrendered and Paris was in the hands of the Commune. Dewey took his cargo to London to be disposed of and returned to the United States. Upon his arrival, he was assigned to the torpedo station at Newport, Rhode Island.

Shortly before Christmas, 1872, Susie gave birth to a son, George Goodwin Dewey. However, she failed to recover form the birth and died five days later. Following the death of his wife, Dewey was detached from the torpedo station at his own request and given command of the NARRAGANSETT again. She had now been assigned to survey the Pacific Coast of Mexico and Lower California. This tedious duty in the blazing heat and virtual isolation of the Gulf of California was relieved only by occasional visits to the port of La Pa to refuel and collate data. In July, 1875, Dewey returned to the United States and served two years in Boston as a lighthouse inspector for the Second Lighthouse District. In 1878, he was appointed Naval Secretary to the Lighthouse Board in Washington, DC. The activities of the board during Dewey's four year tour appear to have centered mainly around debating the questions of whether to substitute lard oil for mineral oil in the lamps. During his Washington years Dewey developed a marked preference for life in the capital, but his health was poor and he was glad to accept command of the JUNIATA, an old steam sloop which was under orders for the Orient.

The JUNIATA proceeded leisurely toward Suez, but at Malta, Dewey was hospitalized with an abscess of the liver, complicated by a severe case of typhoid. He remained in the British hospital for over a year, and at times his doctors doubted that he would live. In the spring of 1882, he finally left the hospital but was too weak to resume his duties. For two years he traveled from one spa to another in an effort to regain his health. Finally, in 1884, he felt strong enough to accept command of the newly completed steel dispatch boat, USS DOLPHIN.

DOLPHIN was the Navy's first "modern" ship. On her trials, she failed to make the designed speed and her propeller shaft broke in two. The navy refused to accept her. While the government and the DOLPHIN's builders wrangled, Dewey, now a Captain, gladly accepted command of another ship, the steam sloop PENSACOLA. The vessel was assigned to the European Station, where she served as flagship of Rear Admiral Samuel F. Franklin. Once again there was the usual round of balls, reviews, and naval ceremonies which had so impressed Dewey as a midshipman. By 1889, however, as the PENSACOLA's four year cruise drew to an end, he may have grown a bit tired of it all. When his friend Winfield Scott Schley, who was serving as chief of the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting, reminded him that his post would soon be vacant Dewey saw his chance to return to Washington. After a tremendous amount of campaigning, he succeeded Schley in July, 1889.

Dewey's years at the head of the Bureau saw the introduction of such

devices as

electric searchlights and signaling apparatus in all ships of the

"New Navy", as well as the introduction of a modern engine room telegraph

system, which enabled officers on the ship's bridge to signal small variations

in speed to the engine room. Dewey also succeeded in increasing the bureau's

appropriation of funds from Congress to increase the coal allotment. The

newer ships were more dependent on the steam engines than the older vessels

which primarily relied on sails. In his four years as head of the Bureau

of Equipment, Dewey established a reputation as an energetic administrator

and a friend of innovation.

The end of Dewey's tour at the Bureau did not cause any change in his comfortable Washington life. In 1893, he was appointed president of the Lighthouse Board, on which he had previously served as "Naval Member" in the 1880s. After two years, he was assigned as president of the Board of Inspection and Survey, which had the responsibility for inspecting and passing final judgment on all new warships. This duty gave Dewey an opportunity to familiarize himself with the Navy's latest ships. During this assignment, Dewey was promoted to Commodore in May, 1896.

In the spring of 1897, it became known in Washington that the post of commander-in- chief of the Asiatic Squadron would soon be vacant. This was just the sort of isolated, semi-independent command which Dewey desired, and he applied for the post in early June to the Bureau of Navigation. With some political assistance from Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt and Vermont's Senator Redford Proctor, Dewey was selected for the post. On October 21, 1897, Dewey was detached from duty as president of the Board of Inspection and Survey and ordered to proceed to Japan to relieve Acting Rear-Admiral Frederick G. McNair as commander-in-chief of the Asiatic Squadron.

On

New Year's Day, 1898, Commodore George Dewey was rowed out to his new flagship,

the cruiser OLYMPIA, lying at anchor in the roadstead

of Nagasaki. On February 11, the OLYMPIA departed Japan for Hong Kong.

After USS MAINE blew up in Havana Harbor on February

15, Dewey ordered the Asiatic Squadron to Hong Kong, and preparations for

conflict with Spain were commenced. On April 24, 1898, word was recieved

that The US and Spain were at war. The Asiatic Squadron was ordered by

the British to leave Hong Kong. It first moved 30 miles north to Mirs Bayon

the Chinese coast and on the 27th departed for the Philippines. Dewey and

his fleet reached Manila Bay on the evening of April 30, and defeated the

Spanish fleet there the following day.

On

New Year's Day, 1898, Commodore George Dewey was rowed out to his new flagship,

the cruiser OLYMPIA, lying at anchor in the roadstead

of Nagasaki. On February 11, the OLYMPIA departed Japan for Hong Kong.

After USS MAINE blew up in Havana Harbor on February

15, Dewey ordered the Asiatic Squadron to Hong Kong, and preparations for

conflict with Spain were commenced. On April 24, 1898, word was recieved

that The US and Spain were at war. The Asiatic Squadron was ordered by

the British to leave Hong Kong. It first moved 30 miles north to Mirs Bayon

the Chinese coast and on the 27th departed for the Philippines. Dewey and

his fleet reached Manila Bay on the evening of April 30, and defeated the

Spanish fleet there the following day.

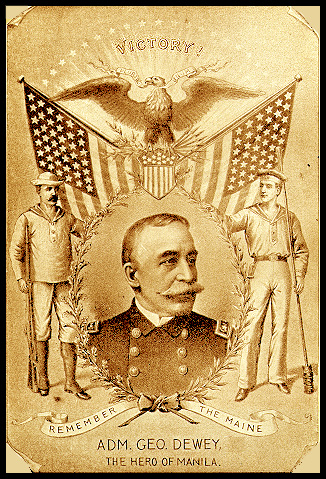

Following the Battle of Manila Bay/Cavite, Dewey fever swept across the United States. He was promoted to Rear-Admiral in mid-May. With the Spanish fleet destroyed, Dewey's Asiatic Squadron blockaded Manila and awaited the arrival of the American army, the first units of which arrived at the end of June. Manila surrendered on August 15, 1998, two days after the United States signed an Armistice with Spain. During the remainder of Dewey's stay in the Philippines, the Navy played a relatively minor part in supressing the Insurrection which had begun against American occupation.

In March, 1899, by an act of Congress, Dewey was appointed Admiral of the Navy. On the late afternoon of May 20, 1899, the OLYMPIA steamed slowly past Corregidor Island and out of Manila Bay. It had been one year and twenty days since Dewey first arrived in the Philippines, during which time he never left the islands. On September 26, 1899, the OLYMPIA reached the coast of the United States. Dewey led a Victory parade in New York City on September 30, 1899. He also participated in celebrations in Washington, DC and Montpelier, Vermont.

On October 29, 1899, Dewey became engaged to a widow, Mrs. Mildred

McLean Hazen. Two weeks later they were secretly married in Washington.

On April 3, 1900, after much pressuring, Dewey announced his candidacy

for President of the United States. He withdrew only a month and a half

later. In the spring of 1900, Dewey was selected to become president of

the newly created General Board of the Navy, whose role was to prepare

for war in peacetime. Serving on this Board for the next sixteen years,

he was instrumental in the development of a larger fleet and greater Naval

presence, including the voyage of the Great White Fleet in 1907. In the

summer of

1901, Dewey was president of the Court of Inquiry which investigated

the conduct of Rear Admiral Winfield Scott Schley prior to and during the

Battle

of Santiago de Cuba. In July, 1903, Dewey was given an additional task

when Secretary of War Elihu Root and Secretary of the Navy William Moody

agreed to establish a Joint Army-Navy Board. Dewey, being the senior officer

on the new board, served as chairman.

George Dewey remained in the Navy and served on both boards until his death on January 16, 1917 at the age of seventy-nine.

This biography was largly base upon the following source. As a service to our readers, those interested in obtaining a copy of the source listed below, simply click on title shown in red and the link will take you to Amazon.com's page on this book.)

Spector, Ronald, Admiral of the New Empire : the Life and Career of George Dewey. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974). ISBN 0-8071-0087-1).