When the USS Maine exploded in Havana, Cuba, on February 15th, 1898, it served as the spark that ignited the Spanish-American War. As the American population was stirred into a frenzy by the popular press, Span knew that it had to protect its possessions in the Caribbean from American aggression. For while Spain was an empire in decline – now merely a shadow of her former glory – the United States was a nation on the rise. The battleship Maine was an early step in the building of a powerful American Navy that would establish the United States as a world power. American shipbuilders, inexperienced at building modern naval vessels, had many problems in completing the Maine, and her construction took ten years to complete. When the Maine was launched, she was already obsolete and was designated a “Second-Class Battleship.” Of limited military value, she was the perfect ship to make a “courtesy call” to Cuba, and assert American power.

But now, the very future of this new steel navy was at risk. The American people were wondering how it could be that one of the new battleships could be so utterly destroyed, and doubts were cast about the decision to build battleships for the United States Navy in the first place. And so, in the Navy Department, there arose a need to show just what the newest battleships were capable of – to provide a demonstration to the American people of the battleships’ worth. This opportunity would present itself at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba, as the bulk of the United States’ “New Navy” confronted what remained of what had once been the mighty Spanish Navy.

The objective of the Americans was to protect the United States and her forces, and to eliminate the threat of the Spanish Naval Squadron. With the declaration of war, the eastern seaboard experienced great anxiety. Some feared that Spain would steam west and shell coastal cities as the English had done in 1812. Therefore the “New Navy” would be required to protect the entire East Coast of the United States from Maine to Texas. In addition to this, troops were being assembled at Tampa, Florida, with the intent of supporting the insurrection and attacking the Spanish Army in Cuba. If the Spanish Navy could be contained, the United States would be able to land an almost unlimited amount of troops and supplies at will. If the Spanish Navy could not be contained, the United States might be prevented from landing anything at all.

And, to be sure, the United States Navy was looking to make a name for itself. The powerful Union Navy of the American Civil War had rotted away. It was not until the 1890s that these ships and guns that were considered “museum pieces” by other navies were beginning to be replaced by modern vessels. The Navy finally had strong advocates, and it was now time to prove what was called “The New Navy” could do. Commodore Dewey had already secured a dramatic victory in the Pacific at Manila Bay. Now it would be up to the most powerful elements of the United States Navy to deploy against Spain in the Atlantic.

The Spaniards did not want a war at all, much

less a clash between the two Navies. After the destruction of the

Maine, the Spanish rescued and cared for the American wounded. When

popular pressure arose for the United States to place demands upon Spain,

virtually all of them short of Cuban independence were granted, in the

hopes of averting a war. But despite the efforts of the Spanish government,

the United States did declare war, and now the Spanish had to think about

protecting their possessions in the Caribbean, as well as to defending

their honor.

On paper at least, the United States Navy seemed more than a match for the forces that the Spanish had available to deploy. At the head of the fleet were four brand-new battleships, designed to conform to the latest in international naval thinking. Conceived as “coast defense battleships” they sat a little low in the water to tackle heavy seas, and they were not particularly fast, although they were not terribly slow either. In terms of armament and armor protection, they were formidable.

The Indiana, Massachusetts and Oregon were all built to the same specifications. Moving at a top speed of fifteen-and-a-half knots, these ships were protected by belt armor of the new extra-hard Krupp steel that was eighteen inches thick. These three battleships boasted a main battery of four 13-inch guns in double turrets fore and aft. Since the big guns took a long time to reload, the battleships also had a wide assortment of smaller, though still powerful, weapons to use against an enemy. A total of eight guns with an 8-inch bore were mounted in twin turrets placed at each of the four corners; four 6-inch guns were mounted on the sides; twenty 6-pounder guns were scattered about the ships; and there were also smaller 1-pounders and Gatling guns fitted as well.

The Iowa was newer and represented the next step in American battleship design. She was larger and heavier, and could travel a knot faster than the three sisters of the Indiana class. She was also protected by the hardened Krupp armor, up to fifteen inches thick. Her main battery consisted of four 12-inch guns, slightly smaller than the 13-inchers on the other three battleships. She had a similar arrangement of eight 8-inch guns mounted at the corners, and she mounted six 4-inch guns versus four 6-inch guns of the earlier design. She mounted the same twenty guns of the 6-pounder size, and also featured a variety of smaller guns as well.

In addition to these was the old “second class battleship” the Texas. Like the Maine, the Texas was powerful when first designed, but the revolution in architecture made her obsolescent by the time that she was to see service. She could travel at seventeen knots, and was fairly well protected behind a foot of armor. She was not as powerfully armed as the modern ships of 1898, mounting a pair of 12-inch guns offset diagonally in an arrangement that seems strange when compared to later battleships, and six 6-inch guns in addition to twelve 6-pounders and assorted other small weapons.

The next class of ship down in size from a battleship was an armored cruiser, and the United States had two powerful units available of this type. The Brooklyn and New York were much faster than battleships, and were able to travel at twenty-one knots. But this speed did not come without a price – these ships had much less armor, mounted fewer guns, and the guns that they did mount were smaller in size. The main batteries of both ships consisted of 8-inch guns, with the Brooklyn mounting eight and the New York mounting six. Both ships mounted 12 guns in the secondary battery, the New York armed with 4-inch quick fire guns while the Brooklyn had the slightly larger 5-inch guns. And, of course, both ships had a variety of 6-pounder and smaller weapons to round out the arsenal.

The Americans also had several “protected” cruisers – lighter and swifter than the armored cruisers, but lacking the armor in their belts as well as in their name. Also available were old monitors – slow, heavily protected shallow-draft vessels with big guns that won fame in the American Civil War performing on America’s rivers. Neither of these types of ships would be see action at Santiago de Cuba.

Finally, to round out the American arsenal were several “Armed Yachts” – small ships sold or donated by individuals and equipped with a few small guns, useful for scouting and patrol duties. Two notable examples of these that would see service at Santiago de Cuba were the Vixen and the Gloucester.

Backing up the warships would be a variety of merchant vessels and support ships. Among them were the collier (coal ship) Merrimac, which plagued the Americans with continuous engine trouble throughout the operation, and several troop transports and supply ships used to transport army units to Cuba, such as the Harvard. A small mine-laying craft named the Resolute would round out the list of participants that played a role in the upcoming battle.

On the Spanish side, their navy was built along

slightly different ideas. They possessed only one second-class battleship,

the Pelayo. The Spaniards favored swift ships since their

empire ranged to the west as far as Central America, and to the east as

far as the island of Guam in the Pacific. The Spanish had six large,

swift, wide-ranging armored cruisers, although they were gunned less heavily

than their American counterparts. These formidable ships were the

Princesa

de Asturias, Emperador Carlos V, Almirante

Oquendo, Viscaya, Infanta

Maria Teresa, and the new Cristobal Colon.

All six ships displaced 7,000 tons except the Colon, which was slightly

smaller. All six mounted two large guns, 11-inchers throughout, except

the Colon, which was to have mounted 10-inch guns. The Colon

was so new, however, that the heavy guns had not yet been mounted, nor

would installing them be possible before the ship was to sail for Cuba.

And all of the cruisers mounted a formidable secondary battery of ten 5.5-inch

guns, with the Colon again differing from her sisters in mounting

half a dozen 4-inch guns as well. And as was common in all cruisers

of the time, these ships mounted 6-pounders (ten each) plus an assortment

of smaller guns as well.

A new type of weapon just appearing on the scene was the self-propelled torpedo. Up until this time, what were called “torpedoes” would today be referred to as mines. But by 1898 the earliest modern torpedoes appeared. This new could speed towards an enemy ship underwater, under its own power, and penetrate the hull of even the mighty battleships below the armor belt and below the waterline. The best thing about the torpedoes is that they could be launched from very small craft, knows as “Torpedo Boats” at the time, but gaining more fame in America during the Second World War under the name “Patrol Torpedo” or “PT” boats.

However, any new weapon, once introduced, leads

to a new type of defense. And in this case, that new defense would

be a totally new class of ship – the “Torpedo Boat Destroyer.” These

in later years would simply be called “destroyers.” These ships boasted

incredibly high speeds in the neighborhood of thirty knots, to be able

to move around the larger, heavier, and slower vessels that they were designed

to protect from the annoying little torpedo boats. Since they would

only be dealing with these tiny, unarmored, and often wooden enemy ships,

they were equipped with only a few very small and rapid-fire guns that

were easy to aim at swiftly moving targets. And while the shell from

a 6-pounder might disable or destroy a torpedo boat, these little guns

had little if any probability of inflicting significant damage on larger,

armored ships. Nonetheless, the Spanish had openly embraced the concept

of the torpedo boat and the torpedo boat destroyer long before they would

gain favor with other navies, and three exceptional early destroyers were

available for service in Caribbean. These were the Pluton,

Furor

and Terror.

When war with Spain appeared imminent, the United States Navy selected Key West as its base of operations. Less than 100 miles from Havana, it was the perfect place from which to enforce a blockade of that city, in the hopes of starving the Spanish Army garrisoned there into submission.

Acting Rear Admiral William T. Sampson was placed in overall command of all Atlantic operations, as well as personal command of the squadron at Key West. His ships there consisted of the battleships Iowa and Indiana, the armored cruiser New York, four smaller cruisers, three of the big-gunned but painfully slow monitors, and a dozen or so smaller ships such as gunboats, torpedo boats, and armed yachts.

Racing to join him was the battleship Oregon, which had been at Puget Sound Naval Shipyard, outside Seattle, Washington. When hostilities seemed imminent, the Oregon steamed south first to San Francisco, then down the West Coast of the United States on a journey that electrified the American people through stories printed in the popular media. But you must remember that this was 1898. The Oregon burned coal, and had to make regular stops all along the way to restock her supply, for when traveling at her maximum speed at sea she burned ten tons of the foul, black substance every hour. And, being 1898, the shortest route from Washington state to Florida involved a route down past Central America, past Peru, past Chile, and then around the southern end of the South American continent. Once in the Atlantic, the journey would involve a voyage north past Argentina, along the entire coast of Brazil, and then northwest into the Caribbean Sea. In the end, the Oregon under the command of Captain Charles F. Clark would perform heroically, completing the unprecedented voyage leaving San Francisco on March 19th to arrive battle-ready at Jupiter Inlet, Florida on 24th of May. The 14,700-nautical mile journey was completed in 67 days at an average speed of twelve knots. This incredible performance leaves one in awe when they stop to think of all the work that had to be performed to accomplish this feat. Burning ten tons of coal an hour, the “black gang” kept feeding the insatiable fireboxes for two straight months, around the clock, using nothing more than shovels. Through her accomplishment, the Oregon made a bold statement to win back the confidence of the American people, both of the battleship as well as the fine crews that served them in the “New Navy.”

But while the Oregon was making her journey, panicky reports continued to pour in stating that “mysterious ships” were seen off the eastern seaboard. The American people wanted protection, and the representatives in Congress of the districts along the coast insisted that the Navy do something to ease their fears. And so, a second squadron was sent to Hampton Roads, Virginia. This was deemed as a safe, central location, whereby a collection of ships could sail north to Maine, or south to Cuba as needed. This was to be known as the “Flying Squadron,” although it was no faster than the forces under Sampson in Key West.

The Flying Squadron was commanded by Commodore Winfield Scott Schley, and consisted of the modern battleship Massachusetts, the old battleship Texas, and the armored cruiser Brooklyn, the protected cruisers Minneapolis and Columbia, and the collier Merrimac, which was to keep the entire squadron well stocked with coal throughout. The Brooklyn served as the Commodore’s flagship.

And so, the American Navy was divided into two forces – one offensive in nature and working to enforce a blockade of Cuba, and one defensive in nature stationed off Virginia (but ready to switch over to offensive operations as soon as a target could be located.)

The Spanish Navy was likewise divided into two forces. The first fleet would consist of the battleship Pelayo and the armored cruisers Emperador Carlos V and Princesa de Asturias along with supporting elements, and was assigned the duties of patrolling the home waters for the duration of the war. But the Almirante Oquendo, Viscaya, Infanta Maria Teresa, and Cristobal Colon were assembled at the Cape Verde Islands along with the Pluton, Furor and Terror, and formed a separate squadron under the finest officer in the Spanish Navy. Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete was fifty-nine years old, and had spent forty-seven of those years in the Navy. He knew Cuba, as he was assigned to the West Indian Station during the first Cuban revolt of 1868-78, and his career had sent him all the way to the Philippines on the other side of the world as well. He was known to be courageous, gallant and competent, and was well known and universally respected.

Prior to being placed in command of the large cruisers, Admiral Cervera had served as Spain’s Minister of Marine, and it was his duty to inspect the Spanish Navy and make recommendations that would allow the Spanish Navy to be in top fighting trim when it was called upon. He had resigned this position when his colleagues had placed personal political gain ahead of the best interests of Spain and refused to support him on his proposed reforms of the fleet. And now he was placed in command of ships and crews that he knew were not all that they could be, but as a true patriot he accepted the assignment without complaint.

The problem that both navies faced was that if they were to sail across the Atlantic with one of their forces, they would be confronted with the combined and concentrated forces of their opponent in home waters. The United States had no motive to send part of her fleet to Spanish waters – they knew that the Spaniards had to come west to support their army in Cuba and lift the blockade.

Admiral Cervera knew that he must sail west,

but he desperately wanted to avoid an immediate rush into the teeth of

the American Navy. He figured that if he waited the impatient and

hungry-for-war Americans would eventually come east to Spain. He

proposed establishing a base in the Canary Islands, and lying there in

wait for the American forces that would certainly steam the Atlantic.

When they arrived, he would combine with the powerful fleet left in home

waters and destroy the tired and far from home units of the United States

Navy. He had all of his captains endorse his plan, and he sent it

off with great hope to Madrid. Despite the soundness of his thinking,

the Spanish government would have no part of it, and they ordered him to

steam to Cuba as soon as practicable. His response indicates that

he understood the impossibility of the mission before him:

“It is impossible for me to give you an idea of the surprise and consternation experienced by all on the receipt of the order to sail. Indeed, that surprise is well justified, for nothing can be expected of this expedition except the total destruction of the fleet or its hasty and demoralized return.”Two days later he updated his progress, and informed his superiors:

“I will try to sail tomorrow… With a clear conscience I go to the sacrifice.”For not only was Cervera terribly outmatched on paper, he knew that his ships were in terrible condition. Three of the four cruisers had defective breech mechanisms and no reliable ammunition for their 5.5-inch guns, the Colon did not have her big guns mounted at all, and the Viscaya, long overdue for a lay-up, had a bottom so fouled that her speed was cut drastically.

The Americans learned of Cervera’s departure from St. Vincent on April 29th. They knew that he was last seen heading west with four armored cruisers and three destroyers. Making the trip would undoubtedly deplete the coal reserves of these ships, and so the Americans knew that when Cervera arrived in the West Indies his first priority would be to restock his coal bunkers. The logical place for him to do this would be at the fortified Spanish port of San Juan, in Puerto Rico.

The Americans feared that Cervera’s squadron might ambush the battleship Oregon, steaming up from South America. While it was true that the Oregon was far superior to all of the Ships, there were nonetheless seven of them, including those pesky and swift torpedo boat destroyers, which were armed with torpedoes themselves. Captain Clark of the Oregon was concerned as well, and he likened the possibility of the potential battle to trying to fight tigers while rattlesnakes scurried about underfoot. And so a decision was made to send Admiral Sampson’s squadron off to Puerto Rico, putting to sea on May 4th with the mission of intercepting Cervera’s squadron and destroying it there.

Sampson brought with him everything that he could, including the monitors that could only manage a best speed of six knots on a calm sea, but the sea was not calm. He was forced to tow the monitors like reluctant children behind his bigger ships to get them to the scene of the battle. Sailing along with him were private yachts filled with the media that scurried about between his ships, trying to gain exclusives and also passing along all the spurious rumors that they had received pinpointing the location of the Spanish fleet at a dozen places. To observers on the warships it looked more like a group of pleasure boats out on a picnic than a military formation.

They arrived at San Juan on May 11th, convinced that Cervera was hiding under the guns of the fortified harbor. The big guns of the American ships commenced a bombardment at 5:30 AM. By 7:30 AM it was obvious that there were no ships in the harbor, and so the shelling ceased. And having achieved nothing, Admiral Sampson ordered his fleet to the west and they began the plodding trip back to Key West.

Sampson was forced to ask himself just where his Spanish counterpart could possibly be. On May 15th he got his answer. A navy dispatch boat approached and informed him that the Spaniards had been at Martinique, a French possession on the eastern boundary of the Caribbean in order to secure coal, but finding none there they had then proceeded on to Curacao, a Dutch possession. Sampson was ordered to proceed to Key West with all possible speed, while Schley was ordered south from Virginia to rendezvous with him there. With the exception of Dewey’s forces in the Pacific, virtually every major warship in the United States Navy was near Cuba or on her way.

Sampson and Schley met in Key West on the 18th, and discussed strategy. Cervera was known to be south of Cuba. It was unlikely that he would try to force the blockade of Havana, which was so close to Key West and the concentrated American forces. It was determined that he would look for a fortified port on the southern coast of Cuba, of which there were two. The first was Santiago de Cuba, at the eastern end of the other. The second, Cienfuegos in the west, was deemed the more likely destination since it was connected with Havana via railroad allowing for easier cooperation between the Spanish Army and Navy. Commodore Schley was assigned a formidable force and ordered to move to Cuba’s southern coast, first inspecting Cienfuegos, and if Cervera was proven not to be there to proceed on to Santiago. Meanwhile, Sampson who had raced ahead of rest of the San Juan participants, would wait for the rest of his lumbering forces to finally return to Key West after their “picnic.”

Schley arrived of Cienfuegos on the 22nd, and caught a glimpse of a few masts and smokestacks poking up beyond the view-blocking terrain at the entrance to the harbor. Some of his men were convinced that they were only merchant ships, but Schley was equally convinced that he had found the warships. He waited. The next day he received a dispatch from Sampson informing him to stay on guard at Cienfuegos, even though rumors already had Cervera in Santiago. On the 23rd another dispatch boat arrived, with orders for Schley to proceed to Santiago with all possible speed, unless he was sure that Cervera was at Cienfuegos. Schley read in the wording that there was still some doubt as to the Spaniards’ location, and so he stayed where he was. On the 25th, a cruiser arrived carrying a duplicate copy of the prior dispatch ordering him to Santiago. Schley informed the captain of the dispatch boat that he was unsure if Cervera was at Cienfuegos or not. The Captain of the cruiser informed Schley of a pre-arranged signal that was to be used by insurgents on Cuba to report information about the position of the Spanish ships to the Americans offshore; three white lights from a single location on the coast. For the last three nights Schley’s lookouts had seen the lights, but they did not know that this was a signal. Furious that he was uninformed, Schley finally got the information from the locals that Cervera was indeed at Santiago. There was no doubt now.

And so Schley set a leisurely pace for Santiago

due to heavy seas and engine trouble on his collier the Merrimac.

On May 26th, when within 20 miles of Santiago, Schley met the Minneapolis,

Yale,

and St. Paul, which reported that they

had not seen the Spanish ships, although they were not specifically assigned

to look for them. Schley did not bother to check for himself.

Instead, in a move that has baffled analysts since 1898, Schley ordered

his fleet to sail west away from Santiago de Cuba, heading for Key West,

fearing that he was about to run out of coal. While only just beginning

his return, he was met by the Harvard carrying orders from the Navy

Department to see to it that the Spanish ships did not leave Santiago.

His response to these orders is considered outrageous today, but must be

considered in a day when naval commanders were used to having considerable

latitude to alter orders in the face of actual "field conditions”:

“Much to be regretted, cannot obey orders of Department. Have striven earnestly; forced to proceed for coal to Key West by way of Yucatan passage. Cannot ascertain anything positive respecting enemy.”Not only was Schley leaving the scene, against orders, he also never personally took a look in the harbor at Santiago de Cuba to confirm if Cervera was or was not positively located. The Secretary of the Navy received Schley’s message and was upset. He sent of a telegram to be delivered to Schley ordering him not to leave the Santiago area, and sent it off “with utmost urgency” written across it. Fortunately for Schley, with the weather calmed and Merrimac repairs complete, he was able to resupply with coal on the 27th at sea. He arrived off the entrance to Santiago de Cuba Bay on the 29th of May, 1898, and now there could be no doubt; for shining in the sun, and moored right across the mouth of the bay was the Cristobal Colon. On the 30th, Schley engaged in a gun battle with the Colon, and although both sides fired with great spirit, there were no hits nor even near misses. All that was accomplished was that the lone Spanish cruiser was inspired to retreat further into the bay to join her sisters, now all relying upon the massive fortifications and hills for protection. Admiral Sampson arrived with his forces on the 31st and took command of the scene.

The only hope for Cervera now was if a storm would scatter the American forces and allow his escape. While it was possible, that was not likely. The entrance to Santiago de Cuba Bay was fortified with a number of big guns. On the western shore were the Socapa Batteries. On the eastern shore were the Morro, Estrella, and Catalina Batteries. And dead ahead on a peninsula looking right down the mouth of the harbor was the Punta Gorda Battery. Just as Cervera was not about to exit the safe haven of the harbor to face the overwhelming American guns, Sampson was not inclined to go into the harbor past the big Spanish guns and among the reported mines to force Cervera out. And so, the solution to the stalemate was obvious; the Army would have a mission in this war at last. General Shafter, in command of United States ground forces, would land near Santiago de Cuba, march overland, capture the city, and drive Admiral Cervera and his ships out, like hounds to the hunters.

The ground campaign is beyond the scope of

this article. Suffice it to say that the Army did leave Tampa, arrive

east of Santiago de Cuba, march overland, engage the Spanish Army, and

succeed in putting pressure on Cervera’s ships forcing him to flee from

the bay and into battle with the United States Navy.

As Admiral Sampson patrolled outside the entrance to Santiago de Cuba Bay, two things were frequently in his vision and upon his mind. The first was the 350-foot width of the channel into the bay. And the second was the old collier Merrimac, 333 feet long and nothing but trouble since the start of the operation. A desire to block the channel to prevent Cervera’s escape, as well as an opportunity to be finally rid of the troublesome collier combined and inspired Admiral Sampson act.

Onboard the Sampson’s flagship the New York was Navy Lieutenant Richmond Pearson Hobson, a thirty-eight-year-old graduate of Annapolis whose specialty was engineering. He was officially aboard the New York to check the behavior at sea of certain structural alterations in the ship’s design. Best of all, he was bright, reliable, and imaginative. In short, he would be the perfect man to devise a plan to cork the bottle in an effort to keep the genie inside.

Hobson’s plan was that the Merrimac would steam at maximum power towards the entrance of the bay. She would then cut power, and glide silently past the forts, unlit, and hopefully without being noticed. When she got as far as Estrella Point, where the channel was narrowest, she would swing perpendicular to the channel, drop both her bow and stern anchors, open up her sea valves, and set off underwater charges attached to her hull. If all went well, she’d sink in about a minute. Sampson found this plan satisfactory and felt that it even had a reasonable chance for success. And so preparations were made.

The attempt to sink the Merrimac was made on June 2, and resulted in a failure to block the channel. The American press called the mission “heroic” which it certainly was, and “totally successful” which it certainly was not.

THE BATTLE OF SANTIAGO de CUBA

Prior to July 2nd, Admiral Cervera had sent as many of his sailors as he could equip with rifles ashore to serve alongside the Spanish Army. With the advances of the United States Army being what they were after their landing, Captain General Ramon Blanco y Erenas ordered Cervera to steam his ships out of the harbor immediately. Blanco was the top military commander in Cuba, and Cervera had little choice but to obey his orders.

Admiral Cervera looked at his options; he could sail by day, or sail by night. By day, his ships would be safe navigating the narrow channel, and avoiding the wreckage of the Merrimac. By night, he would run the risk of damaging his ships and perhaps even blocking the channel himself if an accident were to occur in the dark. As for sneaking out undetected under the cover of darkness, this was quite impossible. The American ships had been shining their searchlights on the mouth of the bay every night since they had arrived on station. Therefore, Cervera concluded that a night time escape would add nothing but danger to his breakout. He thought that the best time to sail would be Sunday morning, when the American crews were at religious services and less likely to be manning their stations. So it was set. The breakout would begin at 9:00 AM on Sunday, July 3rd, 1898. Signals were sent out to the sailors serving ashore with the army for them to return to their ships, and Cervera’s squadron was to have a full head of steam by 2:00 on Saturday afternoon.

Lookouts on Commodore Schley’s flagship, the Brooklyn, spotted the smoke rising from behind the hills and the forts. Schley didn’t know what it meant, but he did know that it meant that something was up. He ordered his little armed yacht, the Vixen, to visit each of the ships in the semicircle that formed the blockade and inform them of the peculiar goings on inside the harbor, and to suggest that they stay in as close as possible during the night. Schley also made a point to make sure that Admiral Sampson in the New York at the opposite end of the blockade was fully informed of what he could see from his end of the line.

Sunday morning dawned gray and overcast, but soon the sun burned this away and a beautiful day with very calm seas broke in the Caribbean off Santiago de Cuba Bay. Despite Schley’s intentions, the formation of ships in the blockade was a little disarrayed that morning. The protected cruisers New Orleans and Newark and the tender Suwanee had all sailed to Guantanamo Bay to coal. And, Schley soon discovered that the powerful Massachusetts had gone with them. There was thus a big gap in the line to the west. At 8:45 AM or so, he was further dismayed to see the New York, Admiral Sampson’s flagship, hoist the signal “Disregard the movements of the commander in chief” and promptly sail out of view to the east.

Admiral Sampson had a meeting scheduled with General Shafter in command of the Army forces in Cuba this Sunday morning and he did not wish to be late. It was unfortunate that he would not be present when Cervera made his breakout. But perhaps more unfortunate was the fact that Sampson had used the New York, one of only two ships in the American fleet that was capable of the speeds necessary to catch Cervera if he made his move. Hindsight dictates that he would have been far better served if he had made the trip in a little steam launch on this calm morning, or even hitched a ride on one of the yachts being employed by the press that were constantly scurrying about. But then, hindsight also dictates that it would be better had he not left at all.

At 9:00 AM Cervera made his move, and his began steaming down the bay. By 9:35, his flagship entered the mouth of the bay, dropped off it’s civilian harbor pilot, and began the dash to safety and freedom. The rest of the squadron would follow at approximately seven-minute intervals.

The navigator on the Brooklyn noticed that a plume of smoke behind a hill was moving. He shouted through his megaphone “Report to the commodore and the captain that the enemy ships are coming out!”

Commodore Schley took a look through his binoculars and exclaimed “We’ll give it to them now! We’ll give it to them now!” Schley then informed an ensign to signal “The enemy is escaping” which had already been done, then said “Signal the fleet to clear for action, then!” Schley looked around in vain one last time for the New York, with his superior on board, and it was nowhere to be seen. Commodore Schley, as second in command, then signaled “Close in” and “Follow the flag.”

The Maria Teresa had begun firing, and a 6-pounder on the Iowa cracked a response. The battle had begun, and the rest of the United States vessels joined in. Only the Teresa at the head of the column could fire at the Americans and only with her forward guns, while virtually all of her opponents, arranged in a rough semi-circle, could hit her from all angles with large numbers of their guns. In a matter of moments, the entire scene was covered with smoke from gunfire so thick that nobody could see what was going on. There was no breeze this morning, and so the smoke just hung there as the American ships began to get underway and the Spanish line began its turn.

Seven miles to the east, Admiral Sampson was wearing his spurs and leggings and ready to go ashore for the horseback ride to the conference with General Shafter. An unexpected hail from a lookout in the foretop froze the admiral at the gangway. Sampson secured a pair of binoculars and took a look for himself. At first he couldn’t see any movement at all, only smoke. But then he saw a dark silhouette against a white cloudbank near the shore, and the shape was immediately recognizable as one of Cervera’s big cruisers. Sampson hoped that the Spanish squadron would be heading east. If so, his New York would be in the perfect position to head them off and his detachment from the blockade would be a heaven-sent blessing. He forgot about the meeting with Shafter and ordered his ship to move to the west with all possible speed to intercept the Spaniards. As he looked through his binoculars, he could tell that the big Spanish ships were turning, but at this range it was not obvious if they were turning towards him or away. He remained optimistic for some time, until he determined that the ships had indeed turned to the west, and not only that – they were pulling away. Admiral Sampson, in command of the fleet, was about to miss the ultimate event in the lifetime of an Admiral – leading the fleet into battle. Frustrated and upset, he headed west hoping against hope that he might be able to arrive on the scene before the battle was over.

As the Spanish column emerged from the bay, directly opposite the entrance to the channel was the Texas and Schley’s flagship the Brooklyn. The Texas, like all the American warships, picked up steam and headed west in pursuit of the gallant Spaniards. All other American warships, that is, except one. The Brooklyn began a turn to starboard – to the east. After the battle, Schley was asked about this peculiar maneuver, and over the years he gave several different answers, none of them particularly satisfactory. The turn was considered, by some, to be “a mistake.”

The Texas had

begun her big turn to the west, picking up speed and firing along the way,

and assumed that the Brooklyn was doing the same up ahead. Captain

John W. Phillips of the Texas describes it like this:

“The smoke from our guns began to hang so heavily and densely over the ship that for a few minutes we could see nothing. We might as well have had a blanket tied over our heads. Suddenly a whiff of breeze and a lull in the firing lifted the pall, and there, bearing towards us and across our bows, turning on her port helm, with big waves curling over her bows and great clouds of black smoke pouring from her funnels was the Brooklyn. She looked as big as half a dozen Great Easterns and seemed so near that it took our breath away.”On the Brooklyn, the navigator cried out to the commodore, “Look out for the Texas, sir!” Schley replied, “Damn the Texas! Let her look out for herself!” The Texas had little choice but to do just that. Backing both engines in an emergency maneuver, the Texas just avoided colliding with the Brooklyn.

On the positive side for the Americans, Schley’s unorthodox maneuver eliminated one of Cervera’s plans. The wily Spanish Admiral knew that only two of the American ships had the speed to catch him – the armored cruisers Brooklyn and New York. As Cervera emerged from the bay, he noticed that the New York was not on station, and dead ahead of him was the Brooklyn. If he could ram the Brooklyn, it would be up to his other ships to simply outrun the slower American battleships. As Cervera headed out of the channel he set a course for the Brooklyn leaning towards the west – his pre-arranged escape route. When Schley turned to the east instead, the ram bow of the Teresa had no target, and so Cervera ordered a more severe turn to the west.

When the Infanta Maria Teresa ventured out into the middle of the American ships it accomplished two things. First, it drew the bulk of the fire from all of the big American guns onto the Teresa. Second, it allowed the next two ships in the column the ability to begin their run to the west relatively unmolested, with the Colon staying close to the shore and the Viscaya a bit further out to protect her. On the Teresa, one of the first hits had struck down Captain Concas, and as the second in command was nowhere to be found, Admiral Cervera assumed command personally.

As the Teresa made the turn to the west, one of her 5.5-inch guns exploded, creating a grisly scene with what at one time had been a gun crew. Big American shells were beginning to find their mark, too – penetrating the hull and starting fires on the wooden deck and superstructure. The entire aft portion of the vessel was a blazing wreck, live steam was being discharged from a broken main, and the ammunition stored there was beginning to explode. “The fire was gaining ground with great rapidity and voracity,” Cervera wrote. “I therefore sent one of my aides to flood the after magazines, but it was impossible to penetrate into the passages owing to the dense clouds of smoke… and the steam escaping from the engine hatch… or to breathe in that suffocating atmosphere.” Cervera knew that it was impossible to continue the fight, and his only decision that could show compassion for his men was to run his ship aground. There was some hope of continuing the fight from the beach, but the without the forward motion of the ship, the flames were now being driven towards the bow by an onshore breeze. Any hope of continued resistance was gone. The Teresa had survived for less than an hour after emerging from the channel, and managed to proceed only half a dozen miles to the west before settling on the beach to burn.

A battleship cannot accelerate at will, and the American ships were not able to keep up with the Spaniards. Only the Oregon had a good head of steam when the Spaniards emerged. What was worse, most of the Americans only had half of their boilers running with the other half totally cold to save coal. Even on the speedy Brooklyn, the engines were decoupled in a fuel saving measure, giving her only half power and limiting her speed to little more than that of the battleships. Recoupling would take twenty minutes, and that was twenty minutes that Commodore Schley did not have, for by now the other three big cruisers were out of the bay and well on their way to escape.

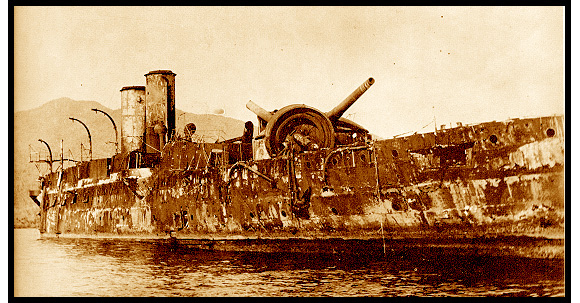

The fourth cruiser in the line was the Almirante Oquendo, and she was following the Viscaya, a little further out to sea than the Colon and providing whatever cover she could to the ship closest to the shore. And so the Oquendo had the misfortune of being closest to the Americans when the Teresa had met her demise, and as a result most of the American fire now concentrated on this cruiser. The fire from all sizes of American guns was having a terrible effect – puncturing the hull with ease, and sometimes even passing through without detonating. Shells that did explode had knocked out most of her guns, and half of her crew (probably 250 men or so) now lay wounded or dead at their stations. Her leadership, too, was falling at an alarming rate. The Oquendo was had not been out of the harbor for fifteen minutes before every man unlucky enough to be in her superstructure was a casualty. Captain Lazaga was struck down early, and his executive officer had just assumed command when a shell from the very next American salvo cut him in two. The third officer took the conn, but was killed when a hit detonated some of the 5.5-inch ammunition stored on board. Within ten minutes, the next three officers in rank were all cut down. The bodies of 130 men were scattered about the deck, draped over ladders, and thrown around the bridge.

The Oquendo’s big guns were not firing with any regularity, and the forward big gun had gotten off only three shots. A messenger sent to investigate the trouble found a bizarre and grisly scene – an 8-inch shell (probably fired by the Brooklyn) had struck the gunport, where the crew was in the process of loading the gun. The 350 pounds of gunpowder being loaded to fire the big weapon was touched off, and the force of the explosion was directed out of the sighting cupola. As a result, all six men of the gun crew were dead without a mark on them, and the officer who was looking out the sighting cupola had his head torn off by the blast. Captain Lazaga, wounded but forced by the terrible attrition of his command staff to resume command, looked at the floating shambles around him and knew that he too had to head for the shore. He ordered that all remaining torpedoes be launched in the hope that one of them might catch one of the American ships in pursuit, and he ordered oil spread on the decks to ensure that the ship would burn beyond any possibility of salvage by the Americans. The senior officer left alive after the action said, “The men… were determined above all that the enemy should not set foot on the ship.” Captain Lazaga is believed to have been consumed in the fire. The Oquendo ran aground about half past ten, less than a mile further down the shore than the Teresa. By the time that she did so her hull was so badly damaged that she immediately broke in two.

When the little torpedo boat destroyers Plutonand Furoremerged, the equally small yacht Gloucester in close and the more distant gunfire being lobbed from greater range by the American battleships confronted them. None of the small ships had big guns, and they all lacked armor. Unfortunately for the Gloucester, she was caught in the tall columns of geysers that the battleship guns were raising along with the two intended targets. Meanwhile, the three ships pecked away at each other with their smaller weapons.

The end came quickly for the Pluton, who was trying to stay close to shore to escape notice. Lieutenant Cabalerro, her second in command, later recounted: “As we were making a great deal of water, we continued close to the shore to Punta Cabrera, and when we were close to the headland we received a 13-inch projectile, which exploded the forward group of boilers, blowing up the whole deck. The ship veered to starboard and struck on the headland, tearing off a great part of her bow… I jumped into the water and reached the shore.”

The Furor was still in the water, although steaming in lazy circles as the result of a grisly accident. Lieutenant Bustamente, who was on deck at the time, recalled, “A shell struck boatswain Duenas, cutting him in two. One part fell between the tiller ropes and it was necessary to take it out in pieces. Another shell destroyed the engine and servomotor, so that the ship could neither proceed nor maneuver.” Bustamente abandoned ship with a few others just moments before another shell struck her in the engine room and blew her to pieces. And in an instant, the Furor was gone – the only one of Cervera’s ships to not make it to the beach. Despite their great speed, neither the Pluton nor Furor would make it more than a few miles down the coast; they did not even make it as far as the Teresa or Oquendo.

At this point, neither Sampson nor Schley was aware of the great victory that they had already achieved. Sampson was too far to the rear to know much of anything that was going on ahead, and Schley was convinced that his casualties were going to be terrible – after all, you couldn’t expect to slug it out like this with the enemy without losing a lot of men. It was now past 10:30, and of the six Spanish ships that steamed out of the bay that morning, only two remained afloat. The swift Cristobol Colon was still maintaining her preferred path close to the shore, and by now had drawn even with the Viscaya which started out of the bay ahead of her. And, once again the Americans concentrated on the closest ship, which at this time was the Viscaya.

The Americans had only three big ships in hot pursuit – the Brooklyn in the lead, with the Texas and the Oregon bringing up the rear. The Iowa and Gloucester were staying in close to shore doing what they could to assist survivors of the Spanish ships in the water, and the Indiana had developed engine trouble so she stayed behind to assist. The most savage fighting was between the Viscaya and Brooklyn, steaming side by side, a little more than half a mile apart.

In capabilities, the two ships were fairly evenly matched. The Viscaya had much heavier armor, and so could withstand the shells from the Brooklyn’s guns. The Brooklyn had more guns, but they had to deal with all of that armor. But the fates of battle and the training of the crews can change the impact of statistics on paper. While the Spanish believed in rapid, mechanical firing at regular intervals, the American officers repeatedly told their crews to take their time and make every shot count. The Americans also had the luxury of having enough ammunition to practice at regular intervals – the Spaniards often fired their guns only once per year. Although the marksmanship of the Americans would be considered terrible by later standards, it was having its effect. Shell after shell slammed into the Viscaya, while virtually all of the shells fired by the Spaniards flew harmlessly overhead beyond the Americans. One of the American gunners complained that he could no longer see the splashes coming up when he fired his gun. “You damn fool,” said the turret-captain, “when you don’t see them drop in the water, you know they’re hitting.”

As the battle raged on, Schley felt the deck jump beneath his feet from a grinding smash. “They’ve landed something on us,” he said, and ordered an apprentice boy below to see how many men were gone. The boy returned and said that a big shell had hit, but it missed everybody. Schley, annoyed, told the boy to keep his wits about him this time and go check again. The boy returned and the same answer came back – two men only slightly wounded. Favor had smiled on the Americans up until now, but their luck had just run out. Chief Yeoman George Ellis had moved to an observation spot ahead of the conning tower to spot the fall of shells fired by the Brooklyn. As he was in this exposed position, a large shell (most likely fired by the Viscaya) struck him in the head. He was decapitated and killed instantly.

The

Viscaya

made a slight turn to the south, in what appeared to be an attempt to set

up a ramming course on the Brooklyn. Soon thereafter, a massive

explosion tore off her bow – either a big shell from the Oregon to the

rear or from the Brooklyn had touched off the warhead in the torpedo

in her forward tube. Captain Eulate, wounded in the head and shoulder,

recounted: “Almost faint from the loss of blood I resigned my command to

the executive officer with clear and positive instructions not to surrender

the ship but rather to beach and burn her. In the sick bay I met

Ensign Luis Fajardo, who was having a serious wound dressed. When

I asked him what was the matter with him he answered that they had wounded

him in one arm but he still had one left for his country. I immediately

convened the officers who were nearest… and asked them whether there was

anyone among them who thought we could do anything more in the defense

of our country and our honor, and the unanimous reply was that nothing

more could be done.”

The

Viscaya

made a slight turn to the south, in what appeared to be an attempt to set

up a ramming course on the Brooklyn. Soon thereafter, a massive

explosion tore off her bow – either a big shell from the Oregon to the

rear or from the Brooklyn had touched off the warhead in the torpedo

in her forward tube. Captain Eulate, wounded in the head and shoulder,

recounted: “Almost faint from the loss of blood I resigned my command to

the executive officer with clear and positive instructions not to surrender

the ship but rather to beach and burn her. In the sick bay I met

Ensign Luis Fajardo, who was having a serious wound dressed. When

I asked him what was the matter with him he answered that they had wounded

him in one arm but he still had one left for his country. I immediately

convened the officers who were nearest… and asked them whether there was

anyone among them who thought we could do anything more in the defense

of our country and our honor, and the unanimous reply was that nothing

more could be done.”

As the Viscaya headed for the shore, the Brooklyn and Texas stopped firing on her. The Texas moved in for a closer look to see if anything could be done for the survivors. Flames were leaping from the deck as high as the funnel tops, and from where he was Captain Philip could hear the shrieks of the sailors caught in the fire. Panic-stricken seamen, some with their uniforms ablaze, were throwing themselves into the water, or crawling to the side and rolling overboard. Others could find no escape from the flames. As was traditional, the crew of the Texas let out a victory cheer, but Captain Philip stopped it at once, saying, “Don’t cheer, boys! Those poor devils are dying!”

By the time the Viscaya had run aground the Iowa was approaching, and Captain Evans saw a new threat to the Spanish sailors emerge. “The Cuban insurgents had opened fire on them from the shore, and with a glass I could plainly see the bullets snipping up the water around them. The sharks, made ravenous from the blood of the wounded were attacking them from the outside.” Evans sent a boat to the shore, warning the rebels to stop firing or to be themselves fired upon – by the big guns of the battleship. The Iowa stayed on the scene and rescued 200 officers and crew from the Viscaya.

That left only the Cristobal Colon. She held a six-mile lead over the Brooklyn with her uncoupled engines and the Oregon, which was showing phenomenal speed for a battleship of her day. The Texas was still in the hunt as well. The chase would continue for a couple of hours, and run for sixty miles. Schley ordered the Oregon to cease fire, so that he could study his maps. And when he saw that the Cuban coast took a turn to the south, he knew that he had the Spaniards at last. Like a football defensive back who “has the angle” on a wide receiver, Schley knew that he could prevent the touchdown. He just had to be patient until the Spaniard made the turn to follow the coast.

He didn’t have to wait quite that long.

At half past noon the Colon had exhausted all of her good Spanish

coal, and switched over to the inferior grade that they had obtained locally

at Santiago. The Colon began to lose speed. As the Oregon

began to close, Schley signaled to her “Try one of your railroad trains

on her,” and a moment later the big guns in the forward turret of the battleship

spoke and sent over a ton of projectiles on their way. They fell

short five times. On the sixth firing, a shell was seen to land ahead

of the Colon. The game was up. Another shot fell just

off the stern of the Spanish cruiser, causing massive concussion damage,

and a steam line burst. Commander Mason who had been watching

the Colon through the ship’s telescope said, “She’s hauled down

her colors and fired a lee gun.”

“What does that mean?” Schley asked.The surprised Mason replied, “Why, it means that she’s struck [surrendered].”“I’m damned glad that I didn’t have to surrender,” Schley laughed. “I wouldn’t have known how.”On the way to the rocks, the Spaniards had opened up the sea valves so that the Colon would be sunk and denied to the Americans. She was aground, and any attempt to move her off as a prize would only sink her. Only now did the commander in chief, Admiral Sampson arrive on the scene. The fight was over, and he had missed it all. Schley signaled, “A glorious victory has been achieved. Details later.” There was no response from the New York. Schley signaled again, “This is a great day for our country.” It was, but not for Admiral Sampson. His cold reply was, “Report your casualties.” Schley then sent signals of congratulations to the Oregon, who with her big guns had saved the day; to the Texas with which he nearly collided earlier; and to the little Vixen, which had come along for the entire length of the chase. With each signal, the receiving ship cheered. The New York remained cold and silent. The seeds that would separate Sampson and Schley in later years had been sown.

When all seemed calm, the little boat Resolute approached at speed and reported that a large Spanish battleship was approaching from the east. Sampson sent Schley and the Brooklyn to investigate. The approaching ship was quickly sighted, and Schley had the Brooklyn ready her portside guns, since only the starboard guns had been engaged during the prior chase. Through the glass Captain Cook could see that the approaching vessel had forward gun turrets. This could not possibly be the Pelayo, unless she had seen a major rebuild or the reference data in Jane’s was terribly out of touch with reality. But there was the flag with the unmistakable red bars hanging from her masthead. A line of signal flags appeared, illuminated by searchlights that illuminated the Americans as well. “This is an Austrian ship,” they read, “Please do not fire.” The Americans had mistaken the red/white/red flag of Austria for the red/yellow/red flag of Spain. The ship was looking for a place to spend the night, and thought that Santiago de Cuba looked like a good port on the map. The Americans asked them instead to anchor at least 20 miles out to sea, as it had been a busy day. The Austrians anchored 40 miles out, just to be sure there was no more confusion. Ironically, the Austrian ship bore the name Maria Theresa.

Shortly after Admiral Cervera was rescued from

the water and issued dry clothing, the Iowa rescued Captain Eulate of the

Viscaya

as

well. He was covered with blood from three wounds, and a grisly handkerchief

was wrapped around his head. As he hobbled to the door of Captain

Evans’ cabin to be tended to, he turned and looked at his former command

now run aground. Captain Eulate saluted his burning ship, “Adios,

Viscaya!”

Just then, flames reached the forward magazine, and the Viscaya

exploded in reply with dramatic effect, sending a pillar of black smoke

high into the sky.

The American order of battle was as follows:

Admiral Sampson's Squadron:

[Flagship] Armored Cruiser NEW YORK under command of Captain French E. Chadwick - 8,200 tons, 21 knots, Six 8-inch, twelve 4-inch, eight 6-pounder, four 1-pounder, four Gatlings.

Battleship IOWA under command of Captain Robley D. Evans - 11,340 tons, 16.5 knots, four 12-inch, eight 8-inch, six 4-inch, twenty 6-pounder, six 1-pounder, four Gatlings.

Battleship INDIANA under command of Captain Henry C. Taylor- 10,288 tons, 15.5 knots, four 13-inch, eight 8-inch, four 6-inch, twenty 6-pounder, six 1-pounder, four Gatlings.

Battleship OREGON under command of Captain Charles F. Clark - 10,288 tons, 15.5 knots, four 13-inch, eight 8-inch, four 6-inch, twenty 6-pounder, six 1-pounder, four Gatlings.

Armed Yacht GLOUCESTER

under command of Lt. Commander Richard Wainwright - 786 tons, 17 knots,

four 6-pounder, four 3-pounder, two Colt machine guns.

Commodore Schley's Squadron:

[Flagship] Armored Cruiser BROOKLYN under command of Captain Francis A. Cook - 9,200 tons, 21 knots, eight 8-inch, twelve 5-inch, twelve 6-pounder, four 1-pounder, four Gatlings.

Battleship (2nd class) TEXAS under command of Captain John W. Phillip - 6,315 tons, 17 knots, two 12-inch, six 6-inch, twelve 6-pounder, four 1-pounder, two Gatlings.

Battleship MASSACHUSETTS under command of Captain F. J. Higginson - 10,288 tons, 15.5 knots, four 13-inch, eight 8-inch, four 6-inch, twenty 6-pounder, six 1-pounder, four Gatlings. (Did not engage, as it was 40 miles away at Guantanamo Bay recoaling.)

Armed Yacht VIXEN - under command of Lieutenant

A. Sharp, Jr. - 800 tons, 16 knots, four 6-pounder, four 1-pounder

The Spanish order of battle was as follows:

Admiral Cervera's Squadron:

[Flagship] Armored Cruiser INFANTA MARIA TERESA under command of Captain Victor Concas y Palau - 7,000 tons, 20.2 knots, two 11-inch, ten 5.5-inch, eight 2.2-inch, eight 1.4-inch, two machine guns.

Armored Cruiser ALMIRANTE OQUENDO under command of Captain Juan Lazaga - 7,000 tons, 20 knots, two 11-inch, ten 5.5-inch, two 2.7-inch, eight 2.2-inch, eight 1.4-inch, two machine guns.

Armored Cruiser VISCAYA under command of Captain Juan Antonio Eulate - 7,000 tons, 20 knots, two 11-inch, ten 5.5-inch, two 2.7-inch, eight 2.2-inch, eight 1.4-inch, two machine guns.

Armored Cruiser CRISTOBAL COLON under command of Captain Emiliano Diaz y Moreu - 6,840 tons, 20 knots, two 10-inch mountings with guns NOT installed, ten 6-inch, six 4.7 inch, ten 2.2-inch, ten 1.4-inch, two machine guns.

Torpedo Boat Destroyer PLUTON under the command of Commander Pedro Vasquez – 400 tons, 30 knots, two 14-pounder, two 6-pounder, two 1-pounder, and two 14-inch torpedo tubes.

Torpedo Boat Destroyer FUROR

under the command of Commander Diego Carlier – 370 tons, 28 knots, two

14-pounder, two 6-pounder, two 1-pounder, and two 14-inch torpedo tubes.

American Losses as a Result of the Battle

The only fatality in the engagement was Chief Yeoman George Ellis, acting as a gunfire spotter just ahead of the conning tower on the Brooklyn.

Ten other American sailors were wounded, one seriously.

Spanish Losses as a Result of the Battle

Cervera's entire squadron was either sunk or run aground. The Spaniards had lost 323 killed and 151 wounded. 70 officers and 1,600 men, including Admiral Cervera himself, were rescued and taken prisoner by the American forces. Only 150 sailors or so made their way back to the Spanish lines at Santiago. All ships had losses, but by far the Furor and Oquendo had suffered the most.

Bachrach, Deborah; “The Spanish-American War”, San Diego: Lucent Books, 1991.

Carter, Alden R.; “The Spanish-American War”, New York: Franklin Watts, Inc.,, 1992.

Chidsey, Donald Barr; “The Spanish-American War – A Behind-the-Scenes Account of the War in Cuba”, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1971.

Dierks, Jack Cameron; “A Leap to Arms – The Cuban Campaign of 1898”, Philadelphia & New York: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1970.

Friedman, Norman; “U.S. Battleships – An Illustrated Design History”, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985.

Hagan, Kenneth J.; “This People’s Navy – The Making of American Sea Power”, New York: The Free Press, 1991.

Hailey, Foster and Lancelot, Milton; “Clear for Action”, New York: Bonanza Books, 1964.

Keller, Allan; “The Spanish-American War – A Compact History”, New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc., 1969.

Lawson, Don; “The United States in the Spanish-American War”, New York: Abelard-Schuman, Inc., 1976.

Leckie, Robert; “The Wars of America – Vol. I: From 1600 to 1900”, New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1968.

Marshall, S.L.A., Brig. General USAR (ret); “The War to Free Cuba”, New York: Franklin Watts, Inc., 1966.

Miller, Nathan; “The U.S. Navy – An Illustrated

History”, New York: The American Heritage Publishing Co. and Annapolis:

Naval Institute Press, 1977.