|

|

"We are all Americans", Native Americans in the Civil War

Introduction | Allegiance to the Federal Government

Civil War Within the Cherokee Nation | In the East

At War's End | Ely Samuel Parker

Stand Watie | Sources of Information and Illustrations

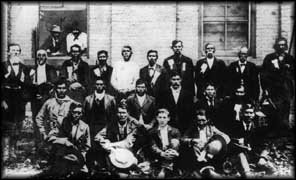

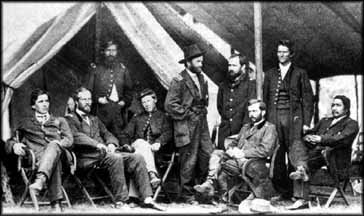

Swearing in of Native Indians recruits

Credit: State Historical Society of Wisconsin

INTRODUCTION

At a time when fear of removal from tribal homelands permeated Native American communities, many native people served in the military during the Civil War. These courageous men fought with distinction, knowing they might jeopardize their freedom, unique cultures, and ancestral lands if they ended up on the losing side of the white man's war.

In an interesting twist of history, General Ely S. Parker, a member of the Seneca tribe, drew up the articles of surrender which General Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Gen. Parker, who served as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's military secretary and was a trained attorney, was once rejected for Union military service because of his race. At Appomattox, Lee is said to have remarked to Parker, "I am glad to see one real American here," to which Parker replied, "We are all Americans."

Read this intriguing account of Native American contributions to the war effort for a fuller understanding of what the conflict meant to "all Americans."

ALLEGIANCE TO THE FEDERAL GOVERNMENT

From "A Creek Warrior for the Confederacy" Approximately 20,000 Native Americans served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War, participating in battles such as Pea Ridge, Second Manassas, Antietam, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and in Federal assaults on Petersburg. By fighting with the white man, Native Americans hoped to gain favor with the prevailing government by supporting the war effort. They also saw war service as a means to end discrimination and relocation from ancestral lands to western territories. Instead, the Civil War proved to be the Native American's last effort to stop the tidal wave of American expansion. While the war raged and African Americans were proclaimed free, the U.S. government continued its policies of pacification and removal of Native Americans. From "A Creek Warrior for the Confederacy" Approximately 20,000 Native Americans served in the Union and Confederate armies during the Civil War, participating in battles such as Pea Ridge, Second Manassas, Antietam, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbor, and in Federal assaults on Petersburg. By fighting with the white man, Native Americans hoped to gain favor with the prevailing government by supporting the war effort. They also saw war service as a means to end discrimination and relocation from ancestral lands to western territories. Instead, the Civil War proved to be the Native American's last effort to stop the tidal wave of American expansion. While the war raged and African Americans were proclaimed free, the U.S. government continued its policies of pacification and removal of Native Americans.

Delaware Indians as shown in "Scouts for the National Army in the West," by Henry Lovie inFrank Leslie's Illustrated, Dec. 6, 1862. Before the war, the Delaware were used as skilled guides and scouts for westward wagon trains, for scientific explorations of the West and in the Rocky Mountain fur trade. Credit: New York State Library and New York State Museum

The Delaware Nation had a long history of allegiance to the U.S. government, despite removal to the Wichita Indian Agency in Oklahoma, and the Indian Territory in Kansas. On October 1, 1861 the Delaware proclaimed their support for the Union. Seeking favor from Washington, 170 out of 201 Delaware men volunteered in the Union Army. A journalist from Harper's Weekly described them as being armed with tomahawks, scalping knives, and rifles.

In January, 1862, William Dole, U.S. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, asked Native American agents to "engage forthwith all the vigorous and able-bodied Indians in their respective agencies." The request resulted in the assembly of the 1st and 2nd Indian Home Guard that included Delaware, Creek, Seminole, Kickapoo, Seneca, Osage, Shawnee, Choctaw and Chickasaw. The Delaware demonstrated their "loyalty, daring and hardihood" during the sacking of the Wichita Agency in October, 1862. Considered a major Union victory, Native American cavalrymen killed five Confederate agents, took the Rebel flag and $1200 in Confederate currency, 100 ponies, and burned correspondence along with the Agency buildings.

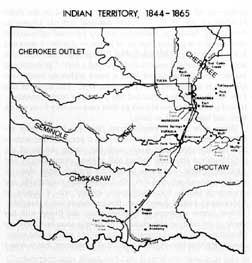

CIVIL WAR WITHIN THE CHEROKEE NATION

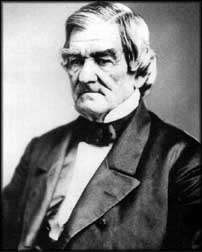

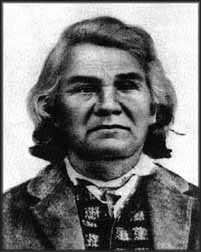

John Ross

Credit: Nat'L Anthropological Archives In 1861, the Cherokee Nation in the West numbered 21,000 and was experiencing its own internal civil war. The Nation divided, with one side led by principal chief John Ross and the other by renegade Stand Watie. Although Ross vowed to remain neutral, Confederate victories at First Manassas and Wilson's Creek forced the Cherokee to reassess their position. The Federal government had abandoned Indian territory early on in the war, and all other Native American nations on the Cherokee borders were Confederate, leaving the Nation vulnerable to Confederate occupation. Stand Watie received a commission as a colonel in the Confederate army and now commanded a battalion of Cherokee. Reluctantly, on October 7, 1861, Ross signed a treaty transferring all obligations due to the Cherokee from the U.S. Government to the Confederate States. In the treaty, the Cherokee were guaranteed protection, rations of food, livestock, tools and other goods, as well as a delegate to the Confederate Congress at Richmond. In exchange, the Cherokee would furnish ten companies of mounted men, and allow the construction of military posts and roads within the Cherokee Nation. However, no Indian regiment was to be called on to fight outside Indian Territory.

Confederate delegates at Washington, D.C. From left to right: John Rollin Ridge, Saladin Ridge Watie (Stand Watie's son ), Richard Fields (formerly of Drew's regiment), Elias Cornelious Boudinot, and William Penn Adair. Confederate delegates at Washington, D.C. From left to right: John Rollin Ridge, Saladin Ridge Watie (Stand Watie's son ), Richard Fields (formerly of Drew's regiment), Elias Cornelious Boudinot, and William Penn Adair.

Credit: University of Oklahoma Press and Archives and Manuscripts Division, Oklahoma Historical Society .

As a result of the Treaty, the 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles, led by Col. John Drew, was formed. Following the Battle of Pea Ridge, Arkansas, March 7-8, 1862, Drew's Mounted Rifles defected to the Union forces in Kansas, where they joined the Indian Home Guard. In the summer of 1862, Federal troops captured Ross who was paroled and spent the remainder of the war in Washington and Philadelphia proclaiming Cherokee loyalty to the Union. In his absence, Col. Stand Watie was chosen principal chief of the Cherokee Nation, and immediately drafted all Cherokee males aged 18-50 into Confederate military service. Watie was a daring cavalry rider who was skilled at hit-and-run tactics. He was considered a genius in guerilla warfare and the most successful field commander in the Trans-Mississippi West. Promoted to brigadier general in May, 1864, Watie was placed in charge of the Indian Cavalry Brigade, which was composed of the 1st and 2nd Cherokee Cavalry and battalions of Creek, Osage and Seminole. He achieved one of his greatest successes at Pleasant Bluff, Arkansas on June 10, 1864, capturing the Union steamboat J.R. Williams which was loaded with supplies valued at $120,000. At the Second Battle of Cabin Creek, (Indian Territory), his cavalry brigade captured 129 supply wagons and 740 mules, took 120 prisoners, and left 200 casualties. At the end of the war, Gen. Stand Watie was the last to surrender, laying down arms two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee, and a month after Gen. E. Kirby Smith, commander of all troops west of the Mississippi.

The Cherokee Nation was the most negatively affected of all Native American tribes during the Civil War, its population declining from 21,000 to 15,00 by 1865. Despite the Federal government's promise to pardon all Cherokee involved with the Confederacy, the entire Nation was considered disloyal, and those rights were revoked.

IN THE EAST

Cherokee Confederate veterans

of the Thomas Legion at the 1901 annual reunion

Credit: North Carolina Dept. of Archives and History.

In the east, many tribes that had yet to suffer removal took sides in the Civil War. The Thomas Legion, an Eastern Band of Confederate Cherokee, led by Col. William Holland Thomas, fought in the mountains of Tennessee and North Carolina. Another 200 Cherokee formed the Junaluska Zouaves. Nearly all Catawba adult males served the South in the 5th, 12th and 17th South Carolina Volunteer Infantry, Army of Northern Virginia. They distinguished themselves in the Peninsula Campaign, at Second Manassas, and Antietam, and in the trenches at Petersburg. A monument in Columbia, South Carolina, honors the Catawba's service in the Civil War. As a consequence of the regiments' high rate of dead and wounded, the continued existence of the Catawba people was jeopardized.

William Terrill Bradby,

a member of the Lumbee Nation

Credit: Smithsonian Institution Credit: Smithsonian Institution

In Virginia and North Carolina, the Pamunkey and Lumbee chose to serve the Union. The Pamunkey served as civilian and naval pilots for Union warships and transports, while the Lumbee acted as guerillas. Members of the Iroquois Nation joined Company K, 5th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry while the Powhatan served as land guides, river pilots, and spies for the Army of the Potomac. During the Civil War there was no distinction made when a Native American joined the U.S. Colored Troops. Well into the twentieth century, the word "colored" included not only African Americans, but Native Americans as well. Individual accounts reveal that many Pequot from New England served in the 31st U.S. Colored Infantry of the Army of the Potomac, as well as other U.S.C.T. regiments.

Union Native American Sharpshooters at

Mary's Heights after the

Second Battle of Fredericksburg

Credit: Library of Congress. Credit: Library of Congress.

The most famous Native American unit in the Union army in the east was Company K of the 1st Michigan Sharpshooters. The bulk of this unit was Ottawa, Delaware, Huron Oneida, Potawami and Ojibwa. They were assigned to the Army of the Potomac just as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant assumed command. Company K participated in the Battle of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania, and captured 600 Confederate troops at Shand House east of Petersburg. In their final military engagement at the Battle of the Crater, Petersburg, Virginia, on July 30, 1864, the Sharpshooters found themselves surrounded with little ammunition. A lieutenant of the 13th U.S. C.T. described their actions as "splendid work. Some of them were mortally wounded, and drawing their blouses over their faces, they chanted a death song and died - four of them in a group."

AT WAR'S END

Henry Berry Lowry was a folk hero to the Lumbee people for his guerilla-style fighting skills and for his leadership against the enslavement of Native Americans.

Credit: North Carolina Department of Archives and History At the end of the war, it was a member of the Seneca tribe, Gen. Ely S. Parker, who drew up the articles of surrender which Gen. Robert E. Lee signed at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Parker, a trained lawyer who was once rejected for army service because of his race, served as Gen. Ulysses S. Grant's military secretary.

At Appomattox, Lee is said to have remarked to Parker: "I am glad to see one real American here," to which Parker replied, "We are all Americans."

ELY SAMUEL PARKER

General Ely Samuel Parker

Credit: National Archives General Parker reached the height of his military career when he wrote up the terms of surrender for Gen. Robert E. Lee to sign at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865.

Parker was born in 1828 in Genesee City, New York, as a Seneca, although much of his life was spent straddling two cultures. For example, Parker acquired knowledge of his grandfather's Iroquoian religion, while he was educated at the local Baptist school. Raised and educated in two cultures, he was a trained attorney and a self-taught engineer. While a captain of engineers with the Rochester regiment of the New York State Militia, he was also a "sachem," one of the honored positions in his tribe and active in Tonawnda affairs.

Parker was described by contemporaries as having a muscular, imposing physical presence. Although he was highly educated and spoke perfect English, enlisted men and officers referred to him as "the Indian" or "Grant's Indian" or "Big Indian." Despite being barred from practicing law and receiving an initial rejection from military service because of his race, Parker rose to General Ulysses S. Grant's staff. In 1863, with Grant's support, he was commissioned as a staff officer for Brig. Gen. John E. Smith. He later joined Grant's staff. His commission as a brigadier general was backdated to April 9, 1865. After the war, Parker remained Grant's secretary and used his military fame to advance his post-war career. Grant served as his best man when Parker married Minnie Sackett, a white woman.

In 1869, then-President Grant appointed him as the first non-caucasian commissioner of Indian Affairs, amid considerable controversy. Corrupt profiteers and overzealous religious leaders led to his political downfall, instigating an investigation by the House of Representatives. Although he was exonerated from accusations of fraud, illegal contracts and numerous violations of law, Parker resigned in disgrace. His subsequent business career failed in the Panic of 1873. He survived in his final years through favors and handouts from former military colleagues.

At the time of his death in August, 1895, Parker was impoverished, leaving his widow with only a carbon copy of the document he had written at Appomattox

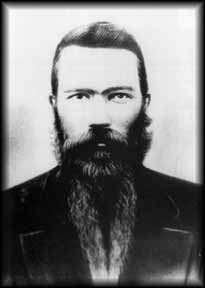

STAND WATIE

Stand Watie Western History Collections,

University of Oklahoma Library

Leader of the Cherokee Nation's pro-southern wing, Stand Watie earned legendary status as a Confederate sympathizer and brilliant field commander, but observed the dissolution of his tribal nation and the Confederacy. Leader of the Cherokee Nation's pro-southern wing, Stand Watie earned legendary status as a Confederate sympathizer and brilliant field commander, but observed the dissolution of his tribal nation and the Confederacy.

Born in December, 1896 in Georgia, Watie was raised as a Moravian by two Cherokee parents. Educated in white schools and educated in western ways, Watie lived in financially well-off surroundings. He was a clerk of the Cherokee Supreme Court as a young man and for more than 40 years was a practicing attorney. Watie's security was disrupted, however, by the 1830 Indian Removal Act to negotiate the removal of Indians west of the Mississippi. He was one of the signers of the 1835 treaty in which Cherokees gave up their Georgia lands for Oklahoma holdings. This controversial treaty set the stage for intense internal strife within the tribe. When the Cherokee Nation divided politically, Watie became leader of the minority faction that sided with the Confederacy, and raised a Cherokee volunteer regiment.

The only Native American to become a brigadier general in the Confederate Army, Watie was considered a genius in guerilla warfare. He was a skilled and daring cavalry rider. His successful capture of the Union steamer J.R. Williams and raids in the west bolstered morale throughout the Confederacy. Watie was the last Confederate general to surrender his command, two months after Appomattox. Although undisputed for his bravery and military skill, Watie's allegiance to the Confederacy was another divisive move that was blamed for the loss of many Cherokee lives during the war and unfavorable treatment of Native Americans in general.

After the conclusion of the Civil War, bitter argument over compensation and property rights overtook Cherokee tribal affairs. Watie moved away to Breebs Town on the Canadian River, resettling his family and forming a tobacco company with a nephew. A federal excise tax imposed the next year on tobacco and distilled spirits did not exempt Indian territory. Watie refused to pay, lost his case in Federal court, and fell into bankruptcy after the plant was impounded for tax foreclosure. The landmark case established legal precedent that a law of Congress could supercede provisions of a treaty.

Watie died in September, 1871 emotionally and financially ruined.

SOURCES OF INFORMATION AND ILLUSTRATIONS

W. David Baird , editor. A Creek Warrior for the Confederacy : The Autobiography of Chief G.W. Grayson. Norman, University of Oklahoma Press, 1988.

Faust, Patricia L ., Editor. Historical Times Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Civil War . New York, Harper and Row, Publishers.1986.

Gaines, W. Craig, The Confederate Cherokees: John Drew's Regiment of Mounted Rifles . Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 1989.

Hauptman, Laurence M. , Between Two Fires: American Indians in the Civil War. New York. The Free Press (Simon and Schuster), 1995.

Starr, Michelle , "Muskogee Autumn," Civil War Times Illustrated, Harrisburg, PA, March 1983.

Internet sources:

"The Civil War in Indian Territory"

http://rebelcherokee.tripod.com/intro.html

"For the Cause"

http://rebelcherokee.tripod.com/waryears.htm

"Warriors for the Union"

http://www.thehistorynet.com/CivilWarTimes/articles/1997/02972_cover.htm |

|

|

|

|

Native American Nations

Native American Nations