|

|

|

- I was drafted in October 1941 from the 10th grade in the days of widespread ruin, robbery, and panic in Moscow. I was drafted despite having my seventeenth birthday just recently. Probably so that a potential soldier wouldn't be left to the Germans.

For about a week I walked as a member of a crew formed at the military commisariat to Il'ino-Zorino, in the Gorkiy oblast. Huge organizing camps were located there. They lodged us in a somewhat semi-dugout shelter for 300-400 men. I was sent to the courses for junior commanders. We went to dig some trenches. They were making us into section commanders, which meant a certain death. Representatives from other branches of military service regularly came to this camp. They selected and took away people who fit with their education. My unfinished 10 grades were considered a very high level of education in those times, so I was claimed. First they brought me to a Guards mortar unit. I was rejected there and sent back because I said that my father had been arrested. Then I went to yet another unit. Again I told them of my father's arrest - I was an honest man, but I should've lied - which I did the third time, when they came to recruit people to become signallers. I decided: "What should I say? I'll say that my father's in evacuation. Who will sort it out?" That's what happened. In February 1942 I finally got to the front, prior to that having nevertheless finished Gorkiy School for radio operators. I was lucky again: I became a signaller in Zapoliarye on the Kandalaksha direction in the 77th Separate Rifle Naval Brigade. Accordingly, our unit consisted of sailors. They were different in that for every normal Russian word they used five curse words. I could speak so myself, but such plentiful, household, normal, natural cursing flew off their tongues - it was amazing to me. Besides that, they constantly unbuttoned their collars so that their striped shirts could be seen, and also tattoos - not criminal, but patriotic: Stalin's profile or a sailor's cap. Germans, not Finns, stood opposite us; SS Nord Division, large, well built, well equipped men. In the summer of 1941 they advanced 150 kilometers from the border, but 70 km from Kandalaksha they were halted, and from the fall of 1941 to the summer of 1944 no active military engagements were carried out in our sector of the front. The frontline was stable for almost two and a half years, we even dug trenches, although the only way to break the frozen ground was with a hack or a crow bar. Our flanks were unoccupied - lakes, bogs. Did you see the film "A zori zdes' tikhiye"? Good picture. Well, they show the same environment in it. Uninhabited. Taking into account our exposed flanks and our love of fighting in winter time, just when bogs and lakes froze, various recon-diversionary operations were launched behind enemy lines.

|

2-3 platoons were assembled, that is 60-90 men, me with a radio transmitter, and we walked around in the German rear. We walked on skis, sometimes we took deer with us which we used to transport ammunition and wounded. We never took dogs - they bark, the bastards. On top of that, we went rather far, to Rovaniemi itself (approx. 200-250 km. - Artem Drabkin), and in such days when no German would ever fight. For example, the New Year in '43 and '44 I greeted behind enemy lines. We set out around December 20, so that in time for Christmas we would be deep in the enemy rear. What German would fight on Christams? But Russians will. There it is - Russian insidiousness! We attacked German garrisons and strong point, mined roads. We always commesurated our forces, that's why abortions happened frequently - intelligence was rarely reliable: It could turn out that a strong point wouldn't be as simple as reconnaissance reported, or a garrison would turn out to be 200 men instead of 50. Those were very difficult marches: it was cold, and scary, and hard. Just try to survive for almost three weeks in a 20-30 degree frost! That's right! Although, we were pretty well dressed: valenki (felt boots), quilted pants, winter camouflage coverall, then padded jacket, uniform, warm flannelette underwear, and yet under it regular linen underwear. They gave us vodka and fed 100 grams of bread per day per man. We had American canned meat. Tasty bitch! A large can, there was pork fat inside, which you could spread on top of a slice of bread, and in the middle - a piece of meat the size of a fist. All in all, we didn't starve... salo, dried bread. We even had oil lamps, of the so-called "push-press" variety. It was a small tin, like for preserves, which contained stearin diluted with alcohol. If you ignite this mixture, it burns with a colorless flame. You could warm food or boil water.

|

But why would you burn alcohol - you should drink it! That's why we dragged a rag through it and wrung it out - you could get maybe 50 grams of alcohol, and since we got several of these tins, you could drink a decent amount, although it was of course disgusting, but the remaining candle wax also burns. For weapons, we took submachine guns and grenades into these raids, sometimes one or two Degtiarev machineguns. In 1942 we still had Mosin rifles - that, of course, is an inconvenient thing, and then they gave us PPSh's. There weren't any airdrops or help from the "big land". In general, we hauled everything on our backs: submachine gun, knapsack, radio. Our radio transmitter was American manufactured V-100, with a receive/transmit unit, like a TV of an average size. In receive mode it worked from a BAS-80 battery, which gave 80 V, but for transmit it required additional energy, that's why the so-called "soldier-motor" went with it: a collapsible tripod with pedals, which were supposed to be spun by hands. It was more powerful than our domestic ones, and since we usually went far, we carried it with us. We went on air rarely: there was the fear that we'd be detected. In general, a radio operator's lot was pretty strange: you'd be by yourself all the time. The superiors drove the radio operators to hell out of fear to be detected and plastered by enemy artillery, and at the same time they couldn't do without us, that's why we were always somewhere to the side, in some dug-out, a ditch, a shell crater; you crawl inside and sit there so that you'd always be on call, but you go on air only in an extreme case. Messages brought to us were already encoded as columns of five-digit numbers, so, of course, I didn't know their content.

|

10th Guards Rifle Division 31st Ski Brigade, 25.11.42 Karelian front |

Most of all I remember the winter of '43/'44. That was our most bloody operation. There were 80-90 of us, and we lost 30-40, that is for everyone of us there was another one wounded or killed. That's also when a tragical event occurred. Two brothers served in our unit, and during a fight for a pillbox one of the brothers broke through inside, but the other one, not having noticed that, threw in a grenade and killed him. He grieved so much, so much... Wanted to shoot himself. Just then we received Stalin's order - killed, more so wounded, were not to be left, had to be brought back. We dragged them on "volokushas" - a small plywood boat with a cord. That time I hauled a wounded sailor. All in all, it wasn't hard, but trip was more than one dozen kilometers, plus I had the radio transmitter, a submachine gun, the knapsack I put at his feet... and it wasn't a highway - a hundred times I spilled him on all the hummocks and put him back again. This sailor, I still don't know what his name was, was wounded in the chest, and although I bandaged him, the blood still flowed. What could I do? We did not take a nurse with us. From time to time regaining consciousness, he begged: "Brother, shoot me, shoot me, brother..." I nevertheless did bring him back, but he died right away. On top of that, on the approaches to the frontline, we had to get in touch with HQ. The commander, Major Karasev, a severe man, ordered us to set up the radio transmitter, and my partner stuck an 80 V battery into the filament, where it was 2.5 V! Obviously, the tubes all burned out, so it did transmit, but we couldn't receive anymore. The commander screams: "I'll shoot you, scumbags!" Of course, he didn't shoot us, but we didn't get any decorations either. And another time, after returning, we pulled over a bread truck, we were so hungry. Criminal proceedings against all of us were started, and although they managed to hush it up, we were left without decorations again. In general, I wasn't lucky when it came to decorations. In '45 I saved my platoon commander who almost drowned during river crossig, and for saving a commander you were due an award - they didn't give it to me again. Well, I do have an Order of the Red Star, a medal "For Bravery", but not a whole lot... Anyway, a private was not supposed to have many.

|

|

Sometimes we brought prisoners. We tried not to take many: there'd be too much bother from them. Of course, preferably, officers, there isn't much use from lower ranks as "tongues". The prisoners walked with us on skis and even dragged the wounded. German skis were more comfortable. Ours - valenki and soft leather bindings, theirs had "persians", that is, warm boots with the tip bent upward, which was put under a clamp in the skis. When we returned, motor or dog sleds were sent after us, which carried away the prisoners for interrogation, and the wounded - to the hospital. Our fatigue was boundless, monstrous fatigue, monstrous... But we were lucky: we were not the only ones to go out. I heard that some had walked into ambushes, and some had been captured by the Finns, and the Finns were malicious. So I got such a gift from fate, than no one ever gave me and will not anymore - I'm ALIVE. But I might've died, and not just once.

In the summer everything stood still: neither we, nor Germans fought. Our radio transmitter was at the very top of a hill, maybe 300 meters from the frontline, camouflaged among the several trees growing there. Well, the month was July, heat, we undressed and were sunbathing. Suddenly, out of nowhere, a �Focke-Wulf�! He shot a burst at us, then circled and shot another, then started chasing after us. He flew low, 10-15 meters, we could see the pilot laughing, and we, unarmed, buck naked, were running around the green glade. He missed, but it was scary. But otherwise it was boring. Many asked to be transfered to other sectors of the front, but usually in vain: "Sit tight. There's war here also. The Motherland demands you to be where you've been told." Constant fires really got us because both sides were dropping incendiary bombs to burn down the woods. Since there was no war, they made soldiers do something. In particular, we picked berries for hospitals: cloudberry, cranberry, bilberry, currant. A day's norm - turn in a full mess tin to the kitchen. Well, we also set up ourselves: built a saw mill, made dug-outs, built a club for 200 people. There we had performers and watched movies. Held some sporting competitions. Sometimes a store drove in, where for those peanuts we were paid we could buy toothpaste powder, cologne, envelopes for letters. Also had affairs with signaller girls, or censor women from the field post office. Prettier and more literate girls were employed there.

In 1944, when an offensive was being prepared, new, mostly artillery, units started arriving. They were required for breaking through the defenses the enemy built up over the past two and a half years. That's when I saw "Katiushas" for the first time, but I was more amazed by �Andryushas� with their shells resembling tadpoles in shape, packed in wooden crates so that they could be rolled. And then an order came out that anything moving behind enemy lines was to be destroyed, down to dogs. This was in the summer, and scouts noticed naked chicks swimming in a lake and sunbathing, probably a brothel had come to the SS soldiers (where else would girls come from in these backwoods?), so they were plastered with a "Katiusha" salvo. Now I think it was barbarous, but then it was the normal order of business - we laughed about it and that's that. We were all so disposed. Posters depicting a man looking at you and asking: "Have you killed a German?" hanged everywhere. Or, a Slavic type sitting down and holding up three spent cartridges in his palm, and a verse below: "How can he not be proud: three bullets and three dead Fritzes!" Such was the atmosphere, but we didn't have a single soldier who hadn't suffered from the war, hadn't had relatives who died or under occupation.

The offensive began in the summer of 1944 and we almost reached Rovaniemi. We weren't in the first file, but dragged ouselves with radios 200-300 meters behind infantry. That is, even if you do get killed, then only stupidly - no one even aimed at you. Just at that time, we, radio operators, were very much needed, because in the absence of wire communications all coordination of the forces was done through radio. Besides that, I got a promotion, became a sergeant major and the commander of a radio transmitter, two men were under my command.

In December of 1944 our regiment was

transferred to Vologda for rest, rearmament, and replacement. We received new

radios. With the help of vodka I exchanged my PPSh for a PPS

with a folding stock; it pulled to one side during firing, but it was light

and had a box magazine. We were due 75 grams of alcohol per day for each man,

but since we were at the radio transmitter, to the side, they gave us for 10

days at once - 750 gramms, you could get seriously drunk. There was trade on

the basis of this: I gave a flask of alcohol to the Sergeant Major, and he exchanged

my submachine gun. Such was the barter. Same to get boots or a greatcoat of

Canadian blue cloth (it was very valuable since, unlike our domestic ones, it

was pure wool)... A lot of temptations exist in the army, but you have to pay

for them one way or another. And then the second part of my war began.

In January we were transfered to the Western Direction. We

detrained in Eastern Poland, in the town of Ostrow-Mazovetski, and became a

part of the First Belorussian Front under the command of Rokossovskiy. But just

as we arrived, the front split. Rokossovkiy was appointed to command the Second

Belorussian, and Zhukov became the commander of the First Belorussian. They

subordinated us to the Second Belorussian Front. We caught up with the Front

already in Pomerania. Pomerania is a granary, the most agricultural part of

Germany, there were a lot of potatoes and even more alcohol. That's where an

event, occurred which I described in a short story published

in Nezavisimaya Gazeta. At Koslin (Koszalin)* we reached the sea, then turned

east, almost approached Gdynia, then turned back and came to Swinemunde (Swinoujscie).

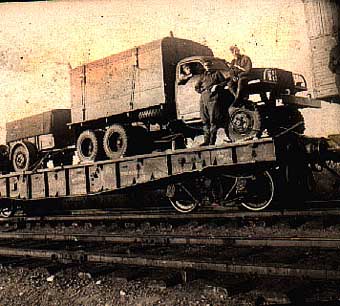

I already served at the regiment radio transmitter, installed on a �Studebaker

US6x6�, "sudar'", as we called it. The radio was American, SCR-399

with an engine, located in a trailer, and a shelter.

Radiostation SCR-399.

Autumn 1945.

|

The truck, by the way, came with a set of driver's instruments

and a leather coat for the driver. If you saw how at the front all our superiors

paraded dressed in leather coats, those were the ones taken out of the set which

came with American Studebakers. Unexpectedly in the evening of May 9 we were

called up to Kolberg (Kolobrzeg) and ordered to load on a barge. They said we

were to be some kind of a landing force. The barge was maybe six meters wide,

we tied our Studebaker on the deck, and loaded the horses and guns into the

opened hold. As soon as it got dark, we set out sailing somewhere. No, get this

- infantry at sea! We were throwing up badly! And on top of that, one of the

cables that held our truck burst. Well, we're thinking, if our Studebaker falls

now, we all get court martialed. There was one sailor among us, a radio operator

Arkashka Kucheriavyi from Leningrad. He crawled along the narrow side between

the sea and the hold, found a chain, and we wrapped the truck around with it.

In the morning we saw the coast, and here they told us: "Denmark. Bornholm".

As we were approaching the port, about six in the morning, we heard shooting,

but while a tug was dragging us in, the shooting stopped, and we disemabarked

in complete calm. Then it turned out that there had been 18 thousand Germans

on the island and after having resisted for a while, they quickly saw reason

and surrendered. Pulled in the walkways, drove out, and I saw civilian life.

Right at the port there was a sign "Cafe", me and a buddy rushed in there, and

saw Danes sitting inside eating ice cream. We also decided to to buy some, took

out the money (we were given German marks), but the vendor jumped away from

us like devil from incense, saying something like "Nicht, Nicht" - meaning,

wrong kind of money. We left emptyhanded. That same day we found out that the

war was over. I turned on the radio receiver, tuned to Moscow, and they already

were making victory announcements there. In that sense radio operators had it

made: you could listen to music or news; although, we were supposed to be on

the same frequency all the time, to be ready for incoming communications. I

was even called up in front of a party meeting because I tuned to music while

on duty. We were on duty in twos, that was demanded by SMERSH: what if you make

contact with the enemy? And this way you're under control. In those times you

had to constantly beware denunciations.

Sergeant Major Yu.

Koriakin, Graiforberg

1945 May 9 |

The war was over, but we spent another 2 months in that

vacation spot. Unfortunately, they had prohibition there, but we swapped gas,

wires, bulbs, batteries for cologne. On June 14 I had my birthday. The guys

say: "You owe us. Organize something tasty, we're sick of this field kitchen

food." What to think of? Right, we live by the sea. Now, you could catch some

fish, but there aren't any nets, therefore - stun it. We had flashlight batteries.

They were valuable because everybody, soldiers and officers, carried flashlights,

but according to TO&E, only we were supposed to have them. I swapped several

batteries for a pile of anti-personnel mines and one anti-tank mine, and then

my partner and I went to the sea, and for a roll of army wire we got a boat

from a Dane. We loaded the mines and fuses in it and started "fishing" half

a kilometer from the shore - stick the fuse in, ingite it, and that's it. As

for the fish, half an hour, and we had half the boat full! We return. A patrol

with submachine guns in front meets us: "Get out!" And the Dane next to them.

He sold us out! "Forward march!" Sergeant major leads us to HQ, swearing: "Look

at that," he says - "they got a new trend, stunning the fish! You're fucking

tearing nets. The fishermen complain to the commander! We get to HQ, we'll show

you!" I don't think they would've made us stand trial, but we could get a reprimand

or be confined to detention. They had already started cleaning up - put up notices

everywhere and conducted meetings on how to behave with the local population.

I tell the sergeant major: "Come on, big deal about stunning the fish, it was

my birthday! Let's swap without looking: you give us freedom, and I give you

a Finnish knife." I had a pretty Finnish knife with a composite handle. He says:

"And the Dane won't turn us in?" "Why? He got our fish." "All right" - he says

- "give me the knife and get out of here." Well, we got back to the crew, told

our story, and the guys say: "To hell with it, the fish food, but go get us

some booze."

Our platoon. Bornkholm,

June 1945

Yu. Koriakin In the photo, stands first from the right |

The next day, after getting off duty, I grabbed binoculars and went to a drugstore to try to exchange it for cologne. Found a drugstore in Ronne. I enter, holding the binoculars in one hand and with the other I make this gesture: smell the palm and rub it over my hair, and do this several times meaning that I need a hair cologne. The drugstore keeper says: "Ja, Ja", - nods, it seems he understood. I give him the 12x binoculars, manufactured by Zeiss, trophy! Great stuff! Beautiful! And he brings a large bottle. I looked at it, smelled it - nice aroma. Well, I'm thinking, it must be cologne. But the glass was dark, couldn't see anything, the cork was scratched. Hauled it back. We poured full glasses, drank for my health, and everybody's eyes popped out - brilliantine for the hair! This Arkashka Kucheriavyi, who saved us with the truck back then, says: "What did you bring, moron? This is brilliantine, it's made with castor oil. We'll get the shits farther than eyesight from it!" Well, I take my submachine gun and the leftovers in the bottle, and go back to the drugstore. I'm trying to get reimbursed, but he's going: "Nicht, Nicht". I got mad, grabbed the gun. He gets out from behind the counter, huge, bigger than me, grabs my arm and drags me to the wall. And on the wall hangs a poster in two languages with a picture of our island's commander, Major General Korotkov. I read the address to the citizens of the Bornholm island that our troops have arrived, liberated you from the Germans, and our task is to secure you a calm life. Immediately report to HQ all cases of undisciplined behavior on the part of the servicemen of the Soviet Army. The Dane stuck my face into this order. Basically, like a beaten dog I dragged myself home with the bottle. Turned around - no one's there. Then I slammed the bottle against the wall, and bad luck again - I got all splattered. Overall, I was left a fool all around, but I still remember this. In the August we started out to fight the Japanese, but didn't get there. That's how the war ended for me. I served for two more years and then went on to MIFI (Moscow Engineering and Physics Institute). No one ever got interested in my father, I even joined the party. Would they have let me, a son of an enemy of the people, go behind enemy lines?

* City names are given as of 1945 when possible. In case the name changed,

the modern name is given in parantheses in the original transcription.

| Recorded

and edited by Artem Drabkin Translated by Oleg Sheremet Photos from the archive of Yu. I. Koriakin and Karelian front veterans board |

|

|

|

|