FRENCH NAVAL LEADERS

AND THE

FRENCH NAVY

IN THE

AMERICAN WAR FOR INDEPENDENCE

|

French ships of the line, Ville de Paris and Auguste, engaged in the famous 'Second Battle of the Virginia Capes' in September 1781. Detail from oil painting by Zveg and held by the US Naval Historic Center, Washington, DC.

|

|

Brief Introduction of the Marine Royale during 1775-1783

The French Navy's role in the success of the American Revolution is seldom acknowledged in general American histories. Yet it is difficult to see how American independence could have been won -- at least in that particular war -- against a regime that was the world's acknowledge leading naval power in terms of ship inventory and recent combat exploits. Certainly, the undisputed expert on the war, General Washington, appreciated the critical importance of naval presence in the North American theater. As long as the British navy could support their army's operations along the eastern coastline, the rebellion was doomed.

The French naval success at the Second Battle of the Virginia Capes in September 1781 was �the keystone' of the Yorktown Campaign, and provides dramatic testimony of the French Navy's contribution to the American cause in that theater of operations. In all due respect to the modest Continental and American state navies, and to the spectacular performances of the American privateers, it was the Royal French Navy that was the only �standing navy' to serve the American army in terms of engaging British naval formations and supporting land operations in North America.

The American rebels did not produce the arms and gunpowder needed to confront the British forces sent to put down the rebellion. Even before the French Alliance in 1778, the American rebels sought and received from Europe the needed mat�riel, the military engineers and other officers with professional skills, and the funds to finance the war. These basic resources that sustained the American forces in the field until Yorktown were delivered largely due to armed escorts of the French Navy. American privateers, operating out of European ports, received significant personnel and mat�riel support directly from the French Navy. It was the French navy that achieved a dominance in possession of the vital West Indian islands that were the life line in logistical support of the Americans. The professional French expeditionary army and siege train that joined Washington in 1780 were transported by a French naval squadron; this factor and the French fleet that appeared off the Virginia coast at the end of August 1781 are symbolic of the �projection of French armed forces across the Atlantic', penetrating the numerically superior British Navy's efforts to isolate the colonies.

However, as important as the North American theater was, the French Navy forced the British to fight a global war that reached from the Hudson Bay to the Indian Ocean, from Newfoundland to the northen coast of South America and western coast of Africa. Eventually France was able to elicit the assistance of the Spanish Navy to at least confront the British numerical strength which helped in the global dispersion of the war. Just as importantly, French naval power continued to maintain a dynamic offensive in the Bay of Bengal, in the Mediterranean, and in the Caribbean as the peace treaties were being negotiated in 1783.

The breath and scope of the French naval participation in the American War for Independence may be hidden from those who are confined to Anglophone sources of the history. The explanation requires an analysis too lengthy to be addressed here. On a positive side, one might note an overview observation Jack Coggins makes in his �Introduction' to Ships and Seamen of the American Revolution � vessels, crews, weapons, gear, naval tactics, and actions of the War for Independence (Stackpole, 1969) p.11:

"The average American history book tends to treat the naval side of the war as a series of ship-vs.-ship incidents and dwells more on its military aspects. But the struggle for North America was fought not only at Trenton, Monmouth, Camden, and King's Mountain. It was fought in the cold, gray seas of the western approaches off Ushant; off Cadiz, and in the shadow of grim Gibraltar; and in the clear tropical water of the West Indies. Renowned as the long fight of the Bonhomme Richard and the Serapis, and the capture by the Thorn of two English sloops of war, it was not by such isolated incidents that independence was won. Ships' actions there were in plenty, and the privateers who swarmed out of American [and European!] ports did grievous hurt to England's merchant marine. But the decisive factor was the often complicated and sometimes almost bloodless behind-the-scenes maneuvering of the fleets of great naval powers." [webpage edit injected within brackets as well as use of bold front]

However, Coggins goes on to say that "a detailed history of the world-wide sea war of 1778-1783 [was] ... beyond the scope" of his book. Fortunately for the Anglophones, there are two scholarly works that provide considerable background on this topic:

Ernest H. Jenkins. A History of the French Navy from Its Beginnings to the Present Day (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1973), especially �Chapter X: Reform: Recovery: Revenge', pp.142-200.

Jonathan R. Dull. The French Navy and American Independence; A Study of Arms and Diplomacy, 1774-1787, (Princeton University Press, NJ, 1975).

Separate webpages directly related to this subject are at:

Supplementary introduction by Vice Admiral Edwin B. Hooper, USN (Ret), from The War at Sea: France and the American Revolution, A Bibliography, Naval History Division, Department of the Navy, Washington DC (US Government Printing Office, 1976).

The French Navy and the Independence of the United States.

Article by Dr. Ulane Bonnel, a specialist in French-American naval history. Her article first appeared in November 1975 issues of the French Navy's magazine Cols Bleus; and later as a commemorative brochure by the Ambassade de France Service de Presse et d'Information , NY, for the Bicentennial of the American Revolution.

The geographic scope of the French naval participation is identified in webpage:

'Table Summary of Movements of French Naval Fleets During the War for American Independence'.

and Adobe Acrobat (pdf) file "Partial Inventory of Killed and Wounded French Soldiers and Sailors in the War for America" at:

http://www.xenophongroup.com/mcjoynt/PertRDNe2.pdf

Other webpages with related topics on this subject are:

'World War Context of the American Revolution'.

'Yorktown Campaign (1781)'.

'Second Battle of the Virginia Capes (1781)'.

'West Indies Score Card During the American War for Independence'.

'Strategic Assessment of the Battle of the Saintes (12 April 1782)'.

'After Yorktown 1781: The War Beyond the Horizon'

This rest of this page is a 'working draft' -- subject to continued revisions -- to acknowledge the contribution of specific French naval leaders listed below.

|

|

|

Directory for topics covered in this webpage:

Links to specific separate pages on others

who influenced the roll of the

French Navy in the American war:

|

-

- Choiseul and de Choiseul-Praslin [not yet activated]

- Louis XVI -- 'The Sailor King' [not yet activated]

- Comte de Vergennes [not yet activated]

- Antoine-Raymond-Gualbert-Gabriel de Sartine, comte d'Alby [not yet activated]

- Charles de La Crois, Marquis de Castries [not yet activated]

|

|

COMTE DE GRASSE

François Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse (1722-1788).

|

Arguably the most famous of the French naval leaders in the American Revolution. His fame was won as victor of the Second Battle of the Virginia Capes, where his fleet of 24 French ships of the line drove off the 19 British ships under Admiral Graves in early September 1781, thus isolating the British forces of Cornwallis at Yorktown.

It was one of the those strategically decisive, tactically indecisive engagements that mark strange turning points in the history of warfare. Late in the morning of 5 September, Admiral Graves' British squadron approached the mouth (between the capes Henry and Charles) of the Chesapeake, and sighted Admiral de Grasse's French squadron just inside the bay. De Grasse immediately set sail, deploying his ships though some were under strength due to being surprised. The two fleets aligned in southeast, parallel courses. The opposing armadas exchanged furious broadside fire, and drifted south until near sunset. The two squadrons maneuvered against one another for three days. Both sides suffered considerable structural damage to their ships and incurred heavy personal casualties. Though no ships were directly sunk or captured during the action, the British ship of the line Terrible was so badly damaged by the French broadsides that the British were forced to burn and sink her before fleeing to New York.

De Grasse's decision to deploy out from the Bay's entrance � rather than merely remain in a blocking formation � was most likely to keep the Bay open for the expected arrival of le Comte de Barras' small squadron transporting the critical French siege artillery for the allied siege of Yorktown. De Grasse had been made aware of Barras' itinerary in a 19 August dispatch. [See link to this below.]

On 9 September, De Grasse took the lead on Graves and returned to the Chesapeake, where he resumed the French blockade by the time the British squadron reached the bay the morning of 13th. Graves dared not continue the contest, and returned to New York for needed repairs -- losing the Terrible enroute. During the engagement at sea, the small French naval squadron, under Barras, slipped into the Chesapeake (10 September) with the French heavy artillery from Newport that would be critical to the Allied siege of Yorktown.

A note of clarification. There had been an earlier 'Battle of the Virginia Capes'. On 16 March 1781, a French squadron under des Touches fought a British squadron under Arbuthnot for about an hour. [See des Touches below]

De Grasse sailed from the Chesapeake 4 November 1781, and took his main fleet to Fort Royal (Fort France today), Martinique, arriving 25 November. While waiting for reinforcements from France before undertaking his next major campaign -- a combined French and Spanish assault to seize British held Jamaica -- de Grasse kept busy with taking a few British held islands in the Lesser Antilles in late 1781 and early 1782. Once the provisions and reinforcements arrived for the Jamaican invasion, De Grasse led a large troop convoy from Saint Domingue on 8 April 1782, with the intention to rendezvous with the Spanish forces. However, the British admiral Rodney intercepted the French off the �les des Saintes, just south of Guadeloupe. De Grasse's quick action managed to save all of the troop transports, but his naval fleet was scattered. Some of the French ships were captured, including de Grasse's flagship with the admiral aboard. [The 12 April 1782 �Battle of the Saintes' is covered on a separate page, the link to which is given below.]

De Grasse was taken as a prisoner to London, where he was treated with considerable respect. (The Ville-de-Paris sunk in an accident before reaching England.) The English king personally returned to de Grasse his admiral's sword. The English also engaged de Grasse in �peace feelers' and then paroled de Grasse to return to France so as to submit the suggestions to the French authorities. De Grasse's report was instrumental in the �Preliminary Articles of Peace' then drafted by the French Foreign Minister, Vergennes.

However, de Grasse was indignant to find that some of the naval officers who served with him at �the Saintes' had disparaged his reputation so as to shield themselves from any blame. In response, de Grasse went directly to the Minister of the French Navy, Castries, and accused many of his subordinate ship captains at the battle of abandoning their stations during the engagement. These subordinates, in turn, made counter charges, which led to a four-months trial held at Lorient. Though the judgment was for de Grasse, and against the former subordinates, King, Louis XVI, was upset that de Grasse had pressed his accusations so aggressively. Unwelcomed at the court, de Grasse retired to his estate outside Paris at ch�teau Tilly.

Meanwhile, he received many expressions of gratitude from America. The US Congress sent him four British cannons taken at Yorktown. In December 1783, the Society of Cincinnati conferred upon him the status of a founding member. General Washington wrote to him:

"Among the many obligations that the United States have gained visa-vis the men of the French Army and Navy who have taken such a noble part in our establishment, that which you have acquired will be profoundly engraved in the spirit of its sons in indelible character, with gratitude and deep respect".

On 18 January 1786, Louis XVI welcomed de Grasse back at Versailles to celebrate a Mass for the order of Saint-Louis. De Grasse returned to live in his Paris residence on rue Saint-Honore, where the Admiral died 14 January 1788. He was buried in the Saint-Roch church, where he remains to this day, and his heart was buried in the church at Tilly.

- See the following Expédition Particulière webpages:

- De Barras' 19 August 1781 Dispatch to de Grasse.

- Second Naval Battle of the Virginia Capes (1781).

- Strategic Assessment of the Battle of the Saints (12 April 1782).

- West Indies Score Card During the American Revolution.

- Mus�e de la Marine, at Grasse, France.

- Tributes to de Grasse.

|

|

A modern note, based upon an article "Four Cannons for the Admiral, A Personal Reminisence" by Oliver Jackson Sands, Jr. in Virginia Cavalcade, Autumn 1981, pp.96-101.

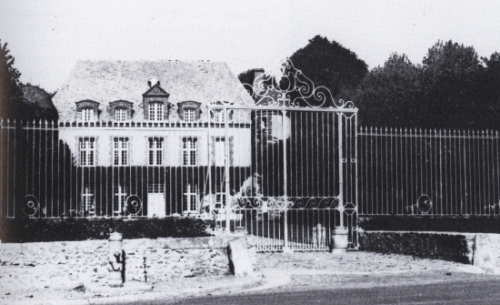

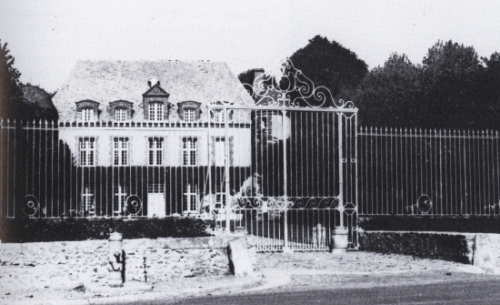

Ch�teau de Tilly, comte de Grasse's home, 35 miles southeast of Paris.

Four British cannons that were captured at Yorktown were shipped by the Americans and placed at the entrance of ch�teau de Tilly. These were taken and melted down during the French Revolution. Five of the admiral's grandchildren escaped to the US and became US citizens. The ch�teau was restored in 1972. Americans had cast and presented replacement cannons at de Tilly in June 1976.

These were cast from a mold made from one of the original British cannon from Yorktown (1781) that was given to the US Military Academy at West Point, NY.

This latter act appears to have been in response to a 1964 initiative of the French society of the Cincinnati, who presented to the US two batteries of five eighteenth-century French cannon to be placed on the battlefield at Yorktown. The cannon were not original, but had been cast in the original eighteenth-century molds that the French had preserved at the Toulon arsenal.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

COMTE D'ESTAING

|

Admiral d'Estaing began his military career as a commander of land forces. He was captured twice by the British in battles for the East Indies, where he began to command naval operations. In 1763, he was made 'Lt. General' in the French Navy, and made Vice Admiral in 1777.

In 1778 he commanded a fleet sent to North America. He participated in poorly coordinated French-American operations at New York (11-22 July) and at Newport (29-31 August). He sailed to the West Indies in November, where he failed in attempt to re take Santa Lucia, but succeeded in capturing St. Vincent and Grenada. He also bested the British in a sea battle on 6 July, but did not follow up. He has generally been criticized as being too cautious a naval commander.

|

Charles Henri Jean-Baptiste, Comte d'Estaing (1729-94). Painting by Pierre Franque, château de Versailles.

|

|

D'Estaing's personal bravery was not doubted, as attested during his return to North American waters in fall of 1779. He directed an allied siege of the British fortifications at Savannah (9 October). He was wounded leading a land assault, and the siege had to be broken off. Some historians blame d'Estaing's failed allied ventures on his autocratic manner, which contrasted dramatically with that of Rochambeau. It is worth noting that d'Estaing had to be �the commanding general' as well as �the admiral' of the French forces in 1778. Whereas, in 1780-81, Rochambeau and de Grasse could focus on these functions separately. Further, d'Estaings's opportunity to develop an environment for combined [inter allied] planning was non existent; nor did he have the benefit of �some lessons learned' gained from a prior French expedition working with the American insurgents. There is little doubt that both Rochambeau and de Grasse benefitted in 1780-81 from the experiences of d'Estaing.

Many narratives that cover the set backs of d'Estaing's operations in the North America fail to address the difficulties encountered by a French navy squadron in waters that were more familiar to the British. De Grasse benefitted by having been with d'Estaing's forces in 1778 and 1779, and was well prepared in 1781 to have made advance arrangements for American pilots to assist. Another irony is that the failed 1779 siege of Savannah (GA) instigated the British evacuation of Newport (RI), which had been the objective of the allied July-August 1778 campaign.

D'Estaing was well liked by the king and his career did not suffer from his 1778-79 exploits in North America. His campaigns in the West Indies ended generally positive for French interests; whereas, his efforts in the American colonies were failures. This contrasted with de Grasse's later experience, which was singularly productive for the American cause, but ended most poorly for France with his defeat and capture in the naval �Battle of Dominica' [or �the Saints'] (12 April 1782) in the West Indies. In early 1783, d'Estaing was placed in command of a new French and Spanish armada being assembled at Cadiz to deploy to the West Indies with the intent to launch another assault against Jamaica. The venture was aborted when the Peace treaties were signed that year. D'Estaing did not fare well in the French Revolution and was executed in April 1794.

| |

Return to top of this webpage.

|

|

|

LE BAILLI DE SUFFREN

Admiral Pierre-André de Suffren Saint-Tropez, called 'Bailli de Suffren', (1729-1788).

Oil painting by Pompeo Batoni (c.1785). Held by Musée National du Château de Versailles et de Trianon.

|

Chevalier-commander André de Suffren has the distinction of being acclaimed as France's finest admiral that fought in the American War for Independence. Suffren's fame is due mostly to his 1782-1783 campaign in the East Indies. As this campaign was fought on 'the other side of the world' -- well off from the horizon of North America and with no American participation -- and is often overlooked in most historical accounts. Even before his ventures in the Bay of Bengal, Suffren had established himself as a well experienced seaman.

From a noble family in Provence, the young Suffren entered the gardes de la Marine in 1743. He followed the tradition of many French naval cadets from Southern France by joining the Ordre des Chevaliers de Malte in 1749. But unlike many others, such as de Grasse, who left the Order so as to marry, Suffren never married, remained a member all his life and achieved the Maltese Order rank of Bailli.

Suffren fought in earlier wars that took him to the West Indies in 1746, and saw him captured by the British the following year in the Bay of Biscay. After some time with the galleys of the Knights of Malta, Suffren returned to the French navy and participated in the capture of the British held Minorca in the Seven Years' War. He was again captured by British in a later battle off Lagos. He went on to command the French xebec [three- masted Mediterranean corsairs' vessel] Caméléon in a campaign against the Barbary Pirates. He served again with the Order of Malta from 1767 to 1771, before returning to the French navy to train officers. Commanding the 64 gun Fantasque, Suffren deployed to North America as part of d'Estaing's fleet in 1778.

Suffren immediatley established his reputation for daring and aggressive maneuvers when he, with his Fantasque plus three frigates (Aimable, Chim�re, Engageante), forced an entrance into Newport harbor (5 August 1778). The surprised British squadron in the harbor panicked and ran aground three frigates and a galley, all of which were burned by their captains. The British scuttled their other ships in an effort to bar the entrance of the main French fleet. However, de Estaing's fleet managed to enter on 8 August. In June of the following year, with d'Estaing in the West Indies, Suffren led the avant garde of the French fleet off Grenada.

Though his Fantasque sustained the main effort (over 60 crew killed) against the opposing British squadron under Byron, Suffren held the French line. After this, Suffren was rewarded by being put in charge of 2 ships-of-the-line and 3 frigates to raid the merchant convoys. Though Suffren was openly critical of d'Estaing's apparent timid naval tactics, the latter did not let this prevent him from recommending Suffren to be given command of a squadron that was to deploy in 1781 to defend Dutch possessions at the Cape of Good Hope.

Suffren led a French naval squadron out of Brest at the same time De Grasse's larger fleet deployed to North America in 1781. Suffren's squadron headed toward the South Atlantic. Enroute, he surprised and seriously damaged an English naval squadron at La Praya in the Cape Verde Islands (16 April 1781). Suffren then went to the Dutch colony at the Cape of Good Hope and off loaded French troops to aid in the defense. Proceeding east, around the Cape, Suffren joined with another French squadron at Île de France [Mauritius], a major French port in the Indian Ocean. The French fleet proceeded east to the Bay of Bengal, where Suffren would for nearly two years maneuver and fight against much better provisioned British naval formations. Suffren's only shore assistance was from the Indian Mysore leader, Hyder Ali, who was also fighting the British, and use of small Dutch ports in Ceylon. Suffren returned to France a hero and was awarded the rank of a vice-admiral.

Suffren's famous 1782-1783 campaign is described in a separate webpage, which is linked below.

See webpage on Suffren's East Indian Campaign (1782-1783) -- the last battles of the American Revolution fought on the other side of the world

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

LA MOTTE--PICQUET

Jean Guillaume Toussaint, comte de La Motte-Picquet de La Vinoy�re (1720-1791).

[known popularly as �La Motte-Picquet']

Bust is displayed in the principal passageway of the frigate La Motte Picquet.

|

La Motte-Picquet was one of the finest of the French naval tacticians in the War for America. He was born at Rennes 1November, 1720, with the name of Picquet, seigneur de La Motte, but was later created by the King comte de La Motte-Picquet. His contemporaries and historians know him as 'La Motte-Picquet'. La Motte-Picquet entered the �gardes marines' [naval cadets] in 1735. He campaigned successively on the coasts of Morocco, in Baltic, to the West Indies [Antilles], to the [East] Indes. Noticed for his skill at meanuvering, he was summoned to Paris in 1775, where he counseled the Secretary of State in preparing the 1776 orders that reorganize the administration of the Navy. Chef d'escadre in 1778, La Motte-Picque participated in the battle of Ouessant [Ushant] (27 July 1778), and crossed next to the English coast where he took 13 prizes in a month.

In the course of the War for American Independence, La Motte Picque distinguishesd himself on several occasions. He rallied d'Estaing's Squadron at Martinique in June 1779, and took part in the fight of the Grenade (July 1779) and the Savannah l'exp�dition (October 1779). Most dramatically was on 18 December 1779, in front of Fort Royal, Martinique, La Motte-Picquet (3 ships of the line) aggressively attacked the English squadron (13 ships of the line, 1 frigate) of Hyde-Parker, the British admiral who blocked the way of a 26 ship convoy coming from France. Hyde-Parker seized 10 of the 26 merchant ships, 4 others ran aground and were burnt. However the skill of La Motte-Picquet's maneuvers and the harshness of his action, drew praise from the British admiral in a message of 28 December:

"The conduct of your Excellency in the affair of the 18th of this month fully justifies the reputation which you enjoy among us, and I assure you that I could not witness without envy the skill you showed on that occasion. Our enmity is transient, depending upon our masters; but your merit has stamped upon my heart the greatest admiration for yourself." [pp.129-130 Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence by Alfred T. Mahan (1912)]

| |

Louis XVI commanded a painting (1786) representing the 18 December 1779 naval engagement. This image is an engraving by Chavane after the original painting by A.I. Rossel de Cercy (1736-1804).

|

On 1May 1781, as commander of a division of 6 vessels and 3 fr�gates, La Motte-Picque intercepted an English convoy carrying the loot from the British admiral Rodney's capture of the dutch island of Saint-Eustache. La Motte-Picque captured 26 of the British cargo vessels. He was made lieutenant general in the Royal Navy in 1782 January. He died at Brest, 10 June 1791, after 52 years of service, 34 campaigns, 10 battles and 6 wounds.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

CHEVALIER DE TERNAY

Charles Louis d'Arsac, Chevalier de Ternay (1722-1780)

Chevalier de Ternay (1722-1780) was a veteran of many wars and had a most distinguished career. Returning from retirement he was put in charge of the squadron to escort Rochambeau's expeditionary corps to North America in 1780. Ternay's sailed out of the Brest harbor 15 April 1780. It consisted of 7 'men of war' [or 'ships of the Line'], 3 frigates, 2 cutters, 1corvette, all of which escorted 35 other ships that were either transports, or war ships serving as supply ships. These ships carried for the most part the French Expeditionary army under le comte de Rochambeau, which proved to be a critical element in the ultimate military victory at Yorktown in 1781.

Chevalier de Ternay is credited with good judgment in his selected route crossing the Atlantic in face of a potential challenge by any of a large number of British naval forces, against which the French large transport formation would be at a disadvantage. As it developed, Ternay did meet a British fleet of four of the line and fifty-gunner under Commodore Cornwallis, in late June, off Bermuda. A short 'running' exchange of cannon fire developed. In spite of the superior number of French warships, and the temptation to seize one of the British ships that had separated from its formation, Ternay discontinued the action. He took his main mission to be conducting his convoy

safely to North America, and would not risk it by attempting to pick up some trophies on the way.

Ternay's squadron entered Narragansett Bay, Newport, Rhode Island, 10 July 1780. Rochambeau and his expeditionary corps began disembarking 12 July. The French naval squadron assumed a strong defensive position and was soon �blockaded' by 13 British ships of the line under Admiral Graves who took a position off Sandy Hook.

Ternay died of a fever in Newport on 15 December 1780. Chevalier Des Touches [Destouches] succeeded Ternay as fleet commander, until the arrival of comte de Barras, in May 1781, who assumed command of the French naval squadron at Newport.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

CHEVALIER DES TOUCHES

Charles-Ren�-Dominique Sochet, Chevalier des Touches (1727-1793)

Admiral Charles-Ren�-Dominique Sochet, Chevalier des Touches took over command of the French naval squadron at Newport, RI, following the death of Admiral Ternay in December 1780. Des Touches was responsible for two initiatives, which were approved by Rochambeau and Washington:

In January 1781, Des Touches dispached a small squadron (L'Eveill� (64) and 3 frigates) under Tilly to attack the British movements in the Chesapeake. They captured the British Le Romulus (44) and brought her back to Newport.

Later, Washington and Rochambeau attempted to execute a combined operation against British forces, under Arnold, in Virginia. Washington dispached La Fayette with his American force to march overland, using some inland waterways, to the Portsmouth area of Virginia. There, Lafayette's force was to be joined by a French force of 1,200+ and 16 siege cannons, under Viomesnil, that was to be transported by Des Touches' naval squadron. Destouches' French convoy was intercepted on 16 March 1781 and fought a British squadron under Arbuthnot for about an hour. Though the British received the worst in the exchange, Des Touches decided not to attempt to force an entrance to the Chesapeake and sailed back to Rhode Island. The result was nearly the opposite of the later, September 1781 'second' battle of the Virginia Capes [See de Grasse, above]. Arbuthnot managed to keep open a line of communications to Arnold's British land army, conducting a campaign of devastation in Virginia. Destouches' failure to land about 1,200 troops compromised the efforts of an American force, commanded by Lafayette, that had marched south and would enter into Virginia in April of that year. The British were able to reinforce in Virginia with troops under General Phillips, who assumed British command in the theater until Cornwallis arrived.

Des Touches remained in command of the French Newport naval Squadron until the arrival of Barras in May 1781.

See webpages:

First Naval Battle of the Virginia Capes (16 March 1781).

Lafayette's Virginia Campaign of 1781.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

COMTE DE BARRAS

Jacques-Melchior (Saint-Laurent), Comte de Barras (1719 - c.1793)

Jacques-Melchior (Saint-Laurent), comte de Barras arrived at Newport, Rhode Island on 8 May aboard La Concorde to take command of the French naval squadron. He was over 60 years old and had considerable naval experience. He commanded the vanguard of d'Estaing's fleet that forced the entry of the Newport harbor in August 1778. He proved to be a cautious, but very capable naval leader. Jacques-Melchior (Saint-Laurent), comte de Barras arrived at Newport, Rhode Island on 8 May aboard La Concorde to take command of the French naval squadron. He was over 60 years old and had considerable naval experience. He commanded the vanguard of d'Estaing's fleet that forced the entry of the Newport harbor in August 1778. He proved to be a cautious, but very capable naval leader.

Barras refused to convoy the French army to the Chesapeake when proposed by Washington and Rochambeau, wisely considering the scheme too risky for his small French naval squadron in waters where much larger number of British ships could assemble against the French. Barras also did not want to move his squadron to Boston as Washington and Rochambeau had decided at the Wethersferd Conference of May 1781. At first he expressed a reluctance to join his squadron with the larger fleet under De Grasse when the allied commanders learned of the latter's intention to go to the Chesapeake and Washington and Rochambeau decided to redeploy their combined armies to the same area. Barras was technically senior in date of rank to de Grasse, but the latter had been give the larger force and designated to be in command of all French naval assets in its operating theater. Barras even considered raiding Newfoundland in stead of supporting the Yorktown campaign. However, he eventually cooperated. Choosing to sail the safest course, keeping out to sea about sixty nautical miles east of Boston, Barras brought the valuable French siege train with him when he entered the Chesapeake Bay 10 September 1781, as fleets that fought the 5 September �Second Battle of the Virginia Capes' were still out to sea.

Later, in February 1782, Barras distinguished himself in the West Indies by capturing Montserrat from the British. Illness forced Barras to depart from Fort royal (Martinique) on 27 March 1782, with La Concorde, to return to France. Barras arrived at Île de Aix on 23 April 1783. He was promoted Vice-amiral 1 January 1791, and retired and died shortly after.

The image of admiral de Barras shown on this page is from Trumbull's painting of the "Surrender of Lord Cornwallis" that is displayed in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda. Formerly this page mistakenly used a print of Paul de Barras', a nephew of the admiral. Trumbull based his portraits in the painting from sketches made in Paris c. 1787.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

MARQUIS DE VAUDREUIL

Louis-Philippe Rigaud Marquis de Vaudreuil (1724 - 1802)

[Second in command under de Grasse, assumed command of the fleet after battle of the Saintes (12 April 1782)]

In December 1778, de Vaudreuil led the French naval squadron that conducted a French army contingent, under the duc de Lauzun, that recaptured Senegal (west coast of Africa) from the British. [Lauzun had temporarly left his newly formed Legion de Volontaires Etrangers de la Marine at Brittany, and would be upset when he returned from Senegal to find that part of this force had been deployed to the West Indies and India in his absence.] De Vaudreuil, left Lauzun (to return to France in a smaller ship) and departed directly from Senegal on board Le Fendant with a squadron (Fendant, Sphinx, R�solue, and Nymphe) and deployed directly to the West Indies where he reinforced d'Estaing. Vaudreuil took part to the July 1779 engagement at Grenada against the British admiral Byron. De Vaudreuil was with d'Estaing at the failed allied siege of Savannah in September - October 1779. De Vaudreuil was back at La Martinique to welcome the arrival of Guichen, the new French naval commander in the West Indies in March 1780. Vaudreuil took part in the Guichen's naval actions against the British admiral Rodney, and then sailed

back to Brest, where he was given the command of the newly built, 80 gun, Triumphant.

Vaudreuil, commanding Le Sceptre, returned to the West Indies in March 1781 as part of de Grasse's fleet. He was present at the Second Battle of the Capes in September of that year. His ship provided 800 soldiers from the vessel's garrison to support the land forces of the French army commander, Choisy, at Gloucester Point during the 1781 September-October Siege of Yorktown.

Vaudreuil was in charge of the first squadron at the April 1782 battle of Les Saintes. He was wounded in the battle, but led reminents of the French fleet back to Saint Domingue (Ha�ti). By 26 April he had gathered with 80% of Grasse's fleet: 28 vessels [ships of the line] and 7 frigates. He sent 12 non-copper covered ships back to Europe.

Keeping Sagittaire and Z�l� to guard the Islands, Vaudreuil sailed to Boston on July 5 to refit the remaining 13 ships of the line (among which, the Magnifique would sink in New England waters). In August 1782, Vaudreuil arrived at Boston to bring naval help for the French and American allied armies, as well as to find wood for his masts. He was promoted lieutenant général 14 August 1782.

During 9-31August 1782, Vaudreuil sent La P�rouse (with Le Sceptre, L'Engageante, L'Astr�e) on a mission to raid British establishments (Prince of Wales, York, and Severn) in the Hudson Bay.

On 24 December 1782, Vaudreuil's squadron departed Boston to transport the infantry regiments [excluding Lauzun's Legion] of Rochambeau's expeditionary army to West Indies (Porto Caballo), as part of a renewed operation against Jamaica. However, news of the peace arrived on 24 March, and the plan was aborted.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

COMTE DE GUICHEN

Luc-Urbain Comte de Guichen (1712 - 1790)

[Succeeds d'Estaing in North America]

|

|

Comte de Guichen's French ship was among other French ships that saluted the USS Ranger under John Paul Jones in the harbor of Quiberon (13 February 1778). This was essentially the first recognition of the American Flag in the form of the �Stars and Stripes' by a foreign Government. [Technically �the first slaute' to a US warship was when the Dutch governor, Johannes de Graaff, of the West Indian island of St. Eustatius, ordered the Fort Orange batteries at the harbor entrance to fire a return salute to the USS Andrew Doria, flying the �Grand Union' flag, on 6 November 1776. The governor was temporally removed -- until 1779 -- by The Netherlands' as that nation was not yet at war with England.]

|

Comte de Guichen entered the navy in 1730 as a �garde de la marine', the first rank in the corps of royal officers. In 1748, he became a �lieutenant de vaisseau', meaning that he could command a frigate. In 1756, he was made �capitaine de vaisseau', meaning he could command a ship of the line. Guichen was awarded the chevalier de Saint Louis in 1748. In 1775, he was appointed to the frigate Terpsichore, attached to an experimental squadron, to develop naval tactical maneuvers. In 1776, Guichen was promoted �chef d'escadre', comparable to �rear-admiral'. When France had became the ally of the Americans in the War of Independence, Guichen commanded the Ville de Paris, as part of the French fleet that deployed in the Manche, and was present at the battle of Ouessant [Ushant] on 27 July 1779.

In March of 1780, Guichen was sent to the West Indies with a strong squadron, where he opposed the British admiral, George Rodney. In the first meeting between them, on 17 April 1780, the two spared off the coast of Martinique. Recognizing that Rodney was a formidable opponent, Guichen maneuvered with caution and skill. He managed to keep �the weather gauge' in three engagements (17 April, and 15 and 19 May), denying the British admiral an opportunity to engage in close action. Most Anglophone authors excuse the British disappointment on the failure of the British ship captains' poor execution of their admiral's command signals. However, Guichen skillful handling his squadrons was exhibited many times during his career. Anglophone naval historians also express their preference of tactics that seek to destroy the opponent's formation, with the logic that such results will leave open an opportunity to later exploit less restricted conditions to pursue the objectives of a campaign. This stated goal of naval warfare is a criticism of the eighteenth century French naval doctrine which did not emphasize so much the sinking of enemy vessels, or even destroying crews, but rather to gain advantage that supported a specific objective or mission � which was in most cases was land oriented [to transport and to land ground forces ashore, and to deny the enemy to do such], and with an ultimate goal to serve in the consolidation of a peace treaty. From the French point of view, Guichen's 1780's operations in the West Indies were quite successful in that admiral Rodney failed to upset the advantage the French were having in that therater. [See West Indies Score Card During the American War for Independence.]

Guichen departed the West Indies on August 1780, trusting the safety of the West Indies (with 9 vessels of the line, 6 frigates,and some smaller ships) to chevalier de Monteil. In October 1780, Guichen served with a combined Franco-Spanish operation under d'Estaing. The following December, he left the allied operations and arrived back at Brest on 3 January 1781.

On 25 June 1781, Guichen departed Brest with 19 French vessels for Cadiz to take in charge a combined Franco-Spanish fleet. On 23 July 1781, 49 vessels of the combined fleet departed Cadiz with 14,000 allied troops that were landed at Minorca. He returned to Brest on 15 September. [The French troops took the last British defense on Minorca on 4 February 1782].

In December 1781, Guichen commanded the force which was to transport stores and reinforcements to the West Indies. On the 12 December, the British admiral Kempenfelt, sighted the French convoy in the Bay of Biscay. Taking advantage of a temporary clearance in the fog, the British admiral, whose battle strength was less than that of the French, boldly attacked the transports. Guichen could not prevent his enemy from capturing twenty of the transports. The other transports fled and returned to port. This marked the only serious failure Guichen endured in the war. He was present with the French and Spanish naval forces when the British admiral Howe prevailed in his brillant and final relief of Gibraltar in October 1782.

Guichen died 13 January 1790.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

BARON DE MONTEIL

Fran�ois-Aymar, baron de MONTEIL (1725-1787)

Monteil was a garde de la marine in 1741, a lieutenant de vaisseau in 1756, capitaine de vaisseau in 1762, chef d'escadre in 1779, and a lieutenant-g�n�ral in 1783. As commandant of the 74 gun Le Conqu�rant he fought and was wounded at the battle of Ouessant [Ushant] (27 July 1778). In August 1780, aboard Le Palmier (74), Monteil took command of the French navy in the West Indies, where he was active in stirring up the Spanish authorities to take more agressive action in the war. He led the French contribution [his flagship, Le Palmier, l'Intr�pide (74), le Destin (74), and le Triton (64)] to assist G�lvez' Pensacola conquest in May 1781. De Monteil commanded Le Languedoc (80), and was chief of the rear-guard at the Second Battle of the Capes. He receied the award of the 'Saint-Esprit' in November 1781. He distinguished himself in the capture of Saint-Christophe in January 1782, but soon after he returned ill to France. He was promoted lieutenant général 8 February 1783.

[It is unfortunate that some modern, non scholarly French accounts incorrectly name a �Bausset' as commanding the French naval contingent at Pensacola. That individual had remained in European waters during the war.]

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

BOUGAINVILLE

Louis-Antoine de BOUGAINVILLE (1729-1811)

|

Bougainville, painted by Émile Lassalle

One of the most remarkable French naval commanders to serve in the American war, though he never held a major command in that conflict. He commanded ships in both fleets of d'Estaing and de Grasse that fought in North America. Bougainville's daring and professional performance was praised on several occasions, but de Grasse blamed Bougainville for errors at the disaster of the Battle of the Saintes (12 April 1782). The critical judgement by a French naval board, against Bougainville, who had a long distinguished record, remains a controversial issue. It did not prevent Bougainville from going on to acquire further distinction in the service of France.

Bougainville's greatest fame is as a French naval explorer, a reputation he acquired prior to serving in the American war. In December 1766, Bougainville sailed from Nantes in the frigate La Boudeuse. He was

accompanied by naturalists and other scientists. He passed through the Strait of Magellan and into the South Pacific in July 1767. In late March 1768 he discovered islands in the archipelago of Tuamoto, now French Polynesia. Continuing he landed on Tahiti about the same time

the British sea captian, Cook, would depart England on his first scientific exploration in August of 1768. Bougainville continued to sail west until reaching what is now named Bougainville reef, just to the east of the Great Barrier reef. His course took him to an Archipelago which he named after Louis XV of France � now the island group of Papua New Guinea. He sailed on to discover Choiseul island, Bougainville Island and the Bougainville Strait. Bougainville's voyage took him to New Britain, Buru in the Moluccas, Batavia (now Jakarta) in Java, before returning in March 1769 to Saint-Malo, in Brittany. While at Tahiti, a woman was discovered aboard Bougainville's ship. She was Jeanne Bar�, who had disguised herself as a seaman and would be the frist female to completely circumnavigate the globe. This added to the other record set in that Bougainville was the first French sea captian to sail round the world in a French ship.

Bougainville's remarkable life spanned many years and included many careers. Before the American Revolution he had published an acclaimed work on mathematics and served with distinction as an army officer in Canada and in Europe during the Seven Years' War. After the American Revolution he survived the French Revolution and served in offices under Napoleon Bonaparte. For further information on Bougainville see:

"A short biography of Louis-Antoine de Bougainville"

|

Return to top of this webpage.

|

|

COMTE DE LA P�ROUSE

Jean Francois de Galaup, comte de La P�rouse (1741 - c.1788)

|

|

Louis XVI was known as �the Sailor King' for his interest in naval exploration and, therfore, his general support for naval improvements that served so well the American cause in the War for American Independence. The above painting is of the French king assigning a French navy veteran of the American War for Independence, La P�rouse, to undertake the expedition described below.

|

Comte de La P�rouse served with notable skill as a ship captain in many of the naval campaigns of the War for American Independence.

As part of Comte d'Estaing's fleet, La P�rouse, commanding the Amazone, captured the British

Ariel that was cruising off the Georgia coast on 10 September 1779. Comte de La P�rouse was promoted to rank of commodore. His next famous exploit was at the Naval battle of Louisbourg (21 July 1781), where he commanded the frigate Astr�e, and along side of La Touche Tr�ville commanding Hermione, fought a squadron of five British frigates escorting a convoy. The small French force captured one British ship by the time night fall ended the engagement and the British ships sought safety at the nearby harbor of Louisbourg. The French squadron returned to Boston with two captured British escort ships (Jack and Thorn) and three merchantmen. His most famous exploit during the war was when Vaudreuil gave him an independent command to raid the Hudson Bay in August 1781. La P�rouse captured the English forts Prince of Wales and York on the Hudson Bay the coastline. He then allowed the British occupants to sail to England in exchange for a promise to release French prisoners held in England.

However, La P�rouse would obtain greater fame after the war as an explorer.

In 1785 he took command of a French government expedition that was to search for the Northwest Passage from the Pacific side and to explore along the coasts of America, China, and Siberia and in the South Seas. He reached Alaska, visited the Hawaiian Islands, Macao, and the Philippines, then went to Japan and Kamchatka, and discovered La P�rouse Strait in 1787. He touched at Samoa and the Friendly Islands. In 1788 he sailed from Botany Bay and was lost at sea. In 1826 the wrecks of what appeared to be his ships were discovered in the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu). La P�rouse's journals have appeared in French in several editions.

|

Return to top of this webpage.

Return to Directory of Topics covered in this webpage.

|

|

Return to

Expédition Particulière

page.

|

|

This page was was posted 17 August 1998; significantly restructured 2 February 2004;

last revised 7 June 2011.

|

Jacques-Melchior (Saint-Laurent), comte de Barras arrived at Newport, Rhode Island on 8 May aboard La Concorde to take command of the French naval squadron. He was over 60 years old and had considerable naval experience. He commanded the vanguard of d'Estaing's fleet that forced the entry of the Newport harbor in August 1778. He proved to be a cautious, but very capable naval leader.

Jacques-Melchior (Saint-Laurent), comte de Barras arrived at Newport, Rhode Island on 8 May aboard La Concorde to take command of the French naval squadron. He was over 60 years old and had considerable naval experience. He commanded the vanguard of d'Estaing's fleet that forced the entry of the Newport harbor in August 1778. He proved to be a cautious, but very capable naval leader.