|

Text and images in this webpage are from an article published as a commemorative brochure by the Ambassade de France Service de Presse et d'Information , New York, NY, for the Bicentennial of the American Revolution. The text is a translation by the author, Ulane Bonnel, of an article which appeared in Cols Bleus, a magazine of the French Navy, of November 8 and 15, 1975. Mme. Bonnel received a doctorate from the University of Paris and became an established specialist in French-American naval history. More on her is at the end of this webpage. Text format has been silghtly revised from the original printed brochure. Editorial additions to the webpage are indicated with an asterisk.

|

|

Directory:*

|

Introduction.

Two hundred years ago, the controversies that had set the English colonies in North America at odds with the mother country since the end of the Seven Years' War degenerated into open conflict. The first shots were fired on April 19, 1775 at Lexington and Concord, near Boston, and armed rebellion quickly spread to the other Atlantic seaboard colonies. The following year, on July 4, 1776, delegates from the 13 colonies met in congress in Philadelphia and adopted the Declaration of Independence. The Fourth of July, the national holiday of the United States, calls to mind each year the significance of that document. In 1976 the celebrations commemorating the bicentennial of American independence reached their peak on July 4. Why was this date chosen? After two centuries of independence, the United States now numbered 50 states and had a population of 250 million, a far cry from the 278,000 inhabitants of the 13 colonies that made this extraordinary bid for independence. In an effort to enable all of today's Americans to feel a sense of personal relationship to the circumstances of the founding of their nation, it was decided to focus the Bicentennial celebrations not so much on the events themselves as on the ideas and principles -- in a word, the philosophy -- expressed with rare felicity in the Declaration that is the keystone of American democracy.

It was not enough to declare a country to be independent; independence had to be won. It was only after eight years of war and a decisive defeat that Great Britain was forced to recognize the independence of its former American colonies. British defeat having been made possible by the aid and the active participation of France, particularly of her Navy, the Bicentennial is, in a large sense, hers as well as that of the United States. Why this can be said, and how it came about, can best be understood by examining the role of the Navy of Louis XVI in the War for American Independence.

Return to page directory.

|

|

* * * *

|

French Naval Reforms after 1763.

The King's Navy had been preparing its revenge since the previous war (1756-1763) and the loss of New France in North America. Known as the Seven Years' War in Europe, and in America as the French and Indian War, the conflict had begun in North America in 1754 and had spread to Europe two years later, in 1756. It had remained, however, predominantly an American and a maritime war, for at stake was the control of the western Atlantic waters from the Caribbean north, together with their islands and their adjacent land masses. French defeat had come as a bitter blow not only to members of naval and maritime circles, but also to the population of coastal provinces and to a surprising degree to the French people as a whole. It was widely recognized that naval power was the key to empire, and so, as soon as peace, disastrous as it was, had been restored, the government of Louis XV, mainly in the persons of the Dukes of Choiseul and of Choiseul-Praslin, set about rebuilding the Navy. Officers were sent on mission to various countries, including Great Britain, to study different aspects of building, administering, maintaining and operating navies. French arsenals were resupplied with wood and other naval stores, with artillery, arms and munitions. A great shipbuilding program was launched for which public subscriptions were organized by provincial and city governments, as well as by Chambers of Commerce. This popular effort was reflected in the names that the proud new ships of the line were to bear: Marseillais, Languedoc, Ville de Paris, Bretagne, Bourgogne. The financial drain on the kingdom proved to be great and the effort had to be reduced during the last three years of the reign of Louis XV. In 1774 it was reported to the Court that England had 142 ships of the line (counting 50-gun ships and those on the ways), 72 of which could put to sea almost immediately in case of war. France at the same time could oppose only 64 ships of the line, 34 of which could be outfitted on short notice. Progress had been made but much remained to be done before the French Navy could match that of Great Britain.

Within the fleet, the training of officers and of men was pursued with more determination and continuity than had been shown before, and training cruises and fleet maneuvers took on new importance and interest. Naval officers tended also to become more scientific-minded and emphasis was placed not only on the techniques of sailing and fighting naval vessels, alone or in formation, but on the sciences of mathematics and of astronomy and on the instruments and techniques of navigation as well.

Intelligence reports from British colonies in America were carefully studied and by the mid - 1760's, the gist of them was "Rebellion against England is coming; all we need to do is to be ready."

Great Britain, albeit victorious, had emerged from the Seven Years' War exhausted and faced with serious financial difficulties, while its American colonies, which had contributed in no small measure to France's defeat, expected reward in the form of greater autonomy in local government and a voice in England's policy concerning their affairs. To the contrary, they found themselves subjected to new military and financial levies, hence the slogan that quickly turned into a cry of revolt: "Taxation without representation is tyranny!" France, meanwhile, was well informed of the state of public opinion in America and followed the course of events with a sympathetic eye. Naturally enough, the "Insurgents" soon turned to France, Great Britain's main rival in America as well as in Europe. In France their emissaries and ship captains were received with kindly circumspection, but in French colonies in America, where the people had already chosen their side in a conflict considered to be inevitable, they aroused genuine enthusiasm. American privateers and supply vessels were -- unofficially -- allowed to use French ports, and little by little the clandestine logistic support of the patriots became organized. In 1776 Louis XVI granted, through the intermediary of Pierre Caron de Beaumarchais, an initial loan to the "Insurgents" that was used to purchase indispensable supplies.

In France as well as in her colonies, public opinion was ahead of the Court. The gilded youth of the time eagerly espoused the cause of the revolutionaries as providing an opportunity to undertake action that was in harmony with their philosophical ideas about liberty and at the same time to take revenge for their defeat by England only a few years earlier. The young and the not-so-young, officers and adventurers, French subjects, foreigners in the service of France, men from all Europe, wished to set sail for America. Their numbers further increased after the dramatic departure of the Marquis de La Fayette and the Viscount de Noailles. Yet the young Louis XVI still hesitated. Before intervening, the King and his counselors wanted to be sure that the rebels had a reasonable chance of freeing themselves from the British Crown and of then maintaining their independence. And since the French Court did not want to enter a war without European allies, it started negotiations to enlist the support of Charles III of Spain, who was more than a little reluctant, however, to be drawn into a new adventure.

Return to page directory.

|

1777 - American Victory at Saratoga.

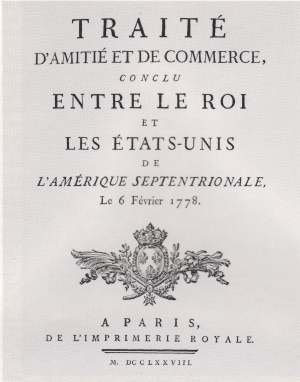

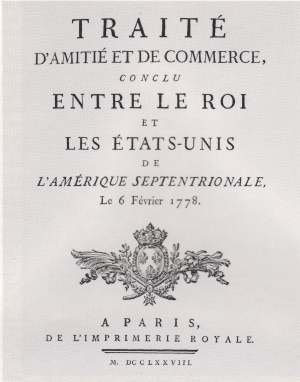

In America, the winter of 1776-1777 was a harsh one in all respects. First of all, the weather was exceptionally severe and General George Washington's small army, underfed and poorly clothed and armed, suffered grievously. From the military standpoint, the British forces seemed to be gaining the upper hand over the patriots without however winning any real victories. Hope was nonetheless on their side, and they expected to defeat the rebels by attrition if not on the battlefield. Then came the battles of Saratoga (September 19 and October 7, 1777) in which the American General Horatio Gates overwhelmingly defeated the British army- of General Burgoyne. The news of this major American victory swept away the remaining hesitation of Louis XVI and his ministers, among whom Vergennes (Foreign Affairs) and Sartine (Navy) were most in favor of intervention. Negotiations with the American envoys, Benjamin Franklin, Arthur Lee and Silas Deane (the latter was soon to be replaced by John Adams) made rapid progress, and on February 6, 1778, the treaties of alliance and trade between France and the United States of America were signed. War with Great Britain thus became inevitable.

The naval forces that were shortly to go into action were more evenly balanced than the 1774 intelligence report cited above indicated.  Far from being able to send out anything near the reported figure of 142 ships of the line, Britain had from 60 to 65 more or less ready for action, whereas France could count on roughly 50. In the peak years of the war, Great Britain was to reach the quite extraordinary total of from 90 to 95 ships of the line as compared to 65 to 70 for France. Their comparison reveals the crucial importance, at least in theory, of the 50 to 55 Spanish ships of the line which, if added to those of France, should have given an overwhelming advantage over the British Royal Navy. It is interesting to note that, according to French naval sources, the total number of warships of the three navies, including transports and supply vessels, reflects the same general proportions: France 211; Spain: 144; Great Britain: 311. Far from being able to send out anything near the reported figure of 142 ships of the line, Britain had from 60 to 65 more or less ready for action, whereas France could count on roughly 50. In the peak years of the war, Great Britain was to reach the quite extraordinary total of from 90 to 95 ships of the line as compared to 65 to 70 for France. Their comparison reveals the crucial importance, at least in theory, of the 50 to 55 Spanish ships of the line which, if added to those of France, should have given an overwhelming advantage over the British Royal Navy. It is interesting to note that, according to French naval sources, the total number of warships of the three navies, including transports and supply vessels, reflects the same general proportions: France 211; Spain: 144; Great Britain: 311.

For the time being, and well realizing that war was imminent, France fitted out two fleets, one at Toulon under the command of Admiral Count d'Estaing and the other at Brest under Admiral d'Orvilliers. In addition, personnel, food and war supplies were dispatched to the French Caribbean colonies.

Return to page directory.

|

1778 - D'Estaing and the Toulon Fleet in America.

The Toulon fleet set sail on April 13, 1778, ostensibly for Brest, but in reality for the shores of North America, and more specifically for the mouth of the Delaware River where nine ships under Britain's Admiral Howe had blocked access to Philadelphia. Among the passengers on board the flagship Languedoc were G�rard, Minister Plenipotentiary of France to the Congress of the United States (which at that time had both legislative and executive powers), and Silas Deane, who had been recalled to America. D'Estaing's fleet, comprising one 90-gun ship, one of 80 guns, six of 74, three of 64 and one of 50, had superior fire power to that of the 12 British ships (six 64-gun ships and six 50's) that had been reported off the "Insurgent" coasts. This superiority, together with the advantage of surprise that was to result from a rapid crossing, was to have ensured the success of D'Estaing's mission.

While this fleet was on its way across the Atlantic, the first shots were exchanged between French and British ships in La Manche [the 'English' Channel*] on June 17, 1778 when the British frigate Arethusa opened fire on the Belle Poule, a French frigate

|

Comte d'Estaing

| commanded by Lieutenant Chadeau de la Clocheterie. Clearly this meant war, and at the moment chosen by the British. Early in March, England had already begun to send reinforcements to its naval bases in America. By the end of May, it had learned of D'Estaing's true destination. Before provoking France into battle on June 17, Britain had already dispatched an additional 13 ships of the line to America under the command of Byron, together with one ship and several frigates to Newfoundland and two ships commanded by Barrington to the West Indies. In so doing, Britain's Royal Navy took a certain risk, since it left Admiral Keppel with only 21 ships of the line to control La Manche. But the British Admiralty worked fast, and despite a variety of difficulties besetting the shipyards, it succeeded in building up Keppel's fleet first to 26 sail, and then to 30. On July 27, 1778 this fleet, with the flagship Victory, engaged the French fleet from Brest, with the Bretagne flying the standard of Admiral d'Orvilliers, in a short battle off Ushant. During the night Keppel returned to Portsmouth, leaving the sea open to Orvilliers, who decided to regain Brest the following day to repair the damage done to his ships. Although neither the British nor the French found cause for satisfaction in this encounter, the British appeared to be the more vexed at not having won the day.

During this war, La Manche [the Channel] was not destined to be the scene of important naval battles, nor were the coasts of Europe in general, with the exception of the approaches to Gibraltar. As was to be expected, France and Great Britain each protected its shores, bases and logistical support lines from enemy attack and tried to inflict the maximum amount of damage on the other by patrolling coastal waters and landfalls, by making better use than in the past of convoys, and by authorizing both naval vessels and privateersmen (privately owned vessels commissioned by the government to engage the enemy) to attack hostile merchantmen. Most of the action was to take place in America, along the eastern seaboard, and in the Caribbean. Important operations, and brilliant ones for the French Navy, also took place off the west coast of Africa and in the Indian Ocean, but they can only be mentioned here.

D'Estaing's fleet, which had set sail from Toulon on April 13, finally dropped anchor at the mouth of the Delaware on July 8. The crossing, which had taken 87 days, undoubtedly set an all-time record for slowness! There were two reasons for this: the sluggishness of two of the ships, and D'Estaing's decisions to exercise and maneuver his fleet during the voyage. As we have seen, the success of his mission depended, however, on the speed with which it was executed. Not having succeeded in taking the enemy by surprise, the French fleet found the Delaware completely free of British warships. As a matter of fact, Britain's land and sea forces had evacuated Philadelphia well before the arrival of the French fleet and had withdrawn to New York via Sandy Hook, where Howe's fleet had remained. Therefore, after having ordered the frigate Chim�re to Philadelphia with G�rard on board, D'Estaing set sail for New York and on July 10 he sighted the city and Howe's fleet, moored behind Sandy Hook. The French fleet then cast anchor at sea, off the Shrewsbury River, and Count d'Estaing asked for American pilots. They did not board the Languedoc, however, until the 16th and then refused the responsibility of taking ships drawing 23 to 25 feet over a sand bar where there was only 211/2 feet of water at high tide. While D'Estaing chafed at this unexpected obstacle, Lieutenant de Ribiers personally took soundings with the American pilots and found only 22 feet of water on the sand bar. During this time, Howe had in any event taken all necessary precautions and would almost certainly have withstood a French attack without great damage. At this point, Congress intervened and provided D'Estaing with an honorable alternative: a joint [and combined*] operation with the American Army against the British at Newport, Rhode Island. On July 22, D'Estaing set course for this new destination.

Early in August, the American Army commanded by General Sullivan and D'Estaing's fleet began to surround English positions by land and by sea. In the beginning everything went smoothly, but on August 9, Admiral Howe's fleet, reinforced by four vessels, appeared before the entrance to the main channel. The next day, taking advantage of a favorable wind extremely rare at that time of year, D'Estaing cut his anchor lines and stood out to sea. The two fleets maneuvered for two days, each trying to gain the advantage over the other. On July 12 gale winds scattered the ships. Skirmishes occurred later between isolated vessels of the two fleets, but Howe escaped and on July 20 D'Estaing's fleet, which had not weathered the storm too well, dropped anchor off Rhode Island.

Meanwhile Admiral Byron had arrived in New York with a fleet of 13 vessels. This alarming news was brought to D'Estaing by the Marquis de La Favette, who boarded the flagship Languedoc as soon as it was ready to receive visitors. D'Estaing's fleet was therefore obliged to leave General Sullivan and the American troops to go to Boston for supplies and repair work. The American general, rendered vulnerable by this decision, was nevertheless able to extricate himself and withdraw his men and artillery without great loss.

Arriving in Boston on August 28, the French fleet anchored in Nantasket Bay, while the Languedoc, the Marseillais and the Protecteur put in at the city for repairs. D'Estaing hoisted his standard on the C�sar and devised a plan to defend the roadstead. On August 31 Admiral Howe was sighted at sea. However he made no attempt to attack and continued on his course to Rhode Island, whence he returned to New York.

While American officials refrained from commenting on the unsuccessful venture at Rhode Island, the same was not true of the people, who severely criticized the "abandonment" of General Sullivan's troops before the enemy.

Insults and blows were sometimes exchanged, and during a brawl between French and American sailors in Boston, two French officers, Mr. de Saint Sauveur and Mr. Le Pl�ville le Peley, were seriously injured. Saint Sauveur died as a result. French and American authorities moved quickly to calm anger and heal wounded pride, and no further incidents of this kind occurred.

Once his ships were repaired, D'Estaing proceeded to the Antilles. On December 9 he dropped anchor at Fort Royal, Martinique. At about the same time English reinforcements arrived in the area, and that part of the Caribbean suddenly became an important theater of operations. The Marquis de Bouill�, Governor of the French Antilles, had already taken the island of Dominica on September 7. Toward the middle of December the English, under the command of Admiral Barrington, took St. Lucia and firmly entrenched themselves there. D'Estaing, alerted on December 13 by an American privateer, weighed anchor on the 14th in an attempt to win back the island. Troops were landed, but both sea and land operations failed and on December 29, at the news of the impending arrival of Admiral Byron, D'Estaing evacuated St. Lucia and withdrew to Martinique.

The year 1778 thus drew to a close, on a note of disenchantment and disappointment. Results were not, however, altogether negligible. The presence in America of a French fleet, proof that Louis XVI was serious about his commitment, had prompted the English to evacuate their troops from Philadelphia and the Delaware River and was partly responsible for the failure of a mission from the Court of St. James that had arrived in New York in June in a last-ditch effort to come to an understanding with the patriots.

Return to page directory.

|

1779 - Operations in the Caribbean.

For the Americans, 1779 was to be a long and painful year of waiting for help that never arrived. Successful campaigns were waged in Illinois by the American Army but the English Army inflicted defeats on the Americans in the South and firmly held Georgia. On the other hand, French forces concentrated in the Antilles chalked up a few victories that were brilliant, although of limited significance. On June 16 and 17, Admiral d'Estaing captured the British island of St. Vincent, thanks mainly to the action of Lieutenant Trolong du Rumain and his Caribbean allies, and on July 4, he took Grenada. During that battle, D'Estaing led the attack himself and the brothers Arthur and Edouard Dillon distinguished themselves, as did Noailles. Byron's fleet came to the aid of Grenada too late; D'Estaing held him off but did not pursue his advantage, thus allowing several British ships to escape when he probably could have captured them. The French fought well, though, and the Admiral requested many favors, such as decorations and pensions, for the officers and men of his fleet. His highest praise was for Captains de Suffren and d'Albert de Rions.

While at Cap Fran�ais on the island of St. Domingue (Hispaniola), D'Estaing received letters from Savannah on July 31 asking him to come to the rescue of that town which had fallen to the British. Although he had received orders to return to France with the Toulon fleet,

|

Lamotte-Picquet

| D'Estaing left St. Domingue on August 16 and arrived 15 days later at the mouth of the Savannah River. On September 2 high winds damaged five ships, including the Languedoc. Forced to wait until the necessary repairs had been made, D'Estaing decided to lay siege to the British in Savannah, convinced that this would be an easy task. The siege began on September 15 but remained ineffective. A direct assault made on October 9 also failed, and on October 18 both French and Americans withdrew. It was a patent failure. Flag officers De Grasse and Picquet de la Motte (more widely known as Lamotte-Picquet) were ordered to remain in the Antilles with two naval divisions. The Toulon fleet returned to France but was dispersed by bad weather and ships straggled in to Brest throughout the month of December. According to the rueful comment of one of his officers, if only D'Estaing's seamanship had matched his bravery, his campaign would certainly have had a different outcome

At the court of Louix XVI, the semi-success of D'Estaing's long campaign brought to light a painful truth: this war was not going to be short, as had been hoped. England, even when at a disadvantage, was still a formidable enemy and difficult to defeat. A respite from war at sea then occurred, while England and France both tried to improve logistic support for their bases in America. Naval warfare took on greater economic overtones, and the protection of merchant ships and of transports emerged as the main task of the two navies. In the case of the Navy of Louix XVI, the divisions headed by De Grasse and by Lamotte-Picquet did a brilliant job of their convoy duties, in addition to engaging in quite a few small skirmishes.

Return to page directory.

|

Spain Enters the War, the South Coast of England Is Threatened.

French diplomatic efforts finally won a commitment from Spain to enter the war against England. In exchange, France had to agree to help Spain retake Gibraltar. As for the principal object � the war in America � Charles III categorically refused to have any association with the "Insurgents," whom he considered to be rebels. Spain therefore declared war on England on June 16. As a matter of fact, Spain and France had already drawn up plans for joint naval operations against Britain, to be synchronized with the landing of an expeditionary force in England. These plans were based upon a study made in 1763-1766 by the Count de Broglie, brother of the Duke de Broglie, Marshal of France, and were used not only in 1779, but also in 1803-1804 by Napoleon. The basic idea was simple: naval forces coming from different directions would converge upon La Manche [the Channel*] and the southern coast of England and would control the seas long enough for troops to cross the Channel and invade England. Essentially, this was an updated version of the scheme developed by Philip II of Spain when he unleashed the Armada against Queen Elizabeth in 1588.

The grand designs of 1779 were no more successful in bringing about the invasion of England than those of 1588. The rendezvous of the fleet out of Brest commanded by Admiral d'Orvilliers with the Spanish fleet of Don Luis Cordova was delayed by illness among French crews. At the end of July, however, the two fleets met, and the combined force totaled 66 ships of the line (30 French and 36 Spanish) and 14 frigates. The English had only 40 ships of the line in home waters to oppose this allied fleet. During this time, the two divisions of the French invasion force had arrived at the coast, one at Le Havre and the other at St. Malo, where 400 transports awaited them.

The Franco-Spanish fleet was, however, having difficulties of its own in the Channel. A terrible epidemic was taking a heavy toll among French seamen and it soon spread to the Spanish ships. Orvilliers, who had left Brest on June 4 and had been continuously at sea since, was running short of food and water. An unfavorable wind delayed the fleet, many of whose ships were too short-handed to perform complicated maneuvers, and prevented it from arriving before Tor Bay in England, the point chosen for a concerted attack. A fortnight was then spent in a vain search for the British fleet commanded by Hardy, after which the allied fleet, no longer able to remain at sea, gave up the chase and limped back to Brest.

The responsibility of Sartine, the French Minister of the Navy, in the failure of these combined operations appears to be heavy, but he laid the blame on the officers and especially on Orvilliers. The public, keenly disappointed, considered the unsuccessful campaign to be a true disaster. In those circumstances, it is not surprising that "Commodore" John Paul Jones' spectacular raid on the British coast seemed by comparison to be an extraordinary feat.

Return to page directory.

|

John Paul Jones.

Jones, a Scottish immigrant and a newcomer in America, and also one of the first officers recruited by the American Navy, was

|

John Paul Jones

|

selected to go to France to carry out various missions and then to take command of the Indien, a vessel being built at Amsterdam. He reached Nantes in December 1777, in command of the famous "Insurgent" frigate Ranger, accompanied by the two prizes he had taken during his voyage, and from there he went to Paris to report to Benjamin Franklin. In February 1778 he took the Ranger into Quiberon Bay where he exchanged salutes on the 14th with Lamotte-Picquet's squadron, firing 13 cannon shots which were returned by nine (the prescribed number for a republic, as for example, the United Provinces of the Netherlands). For the first time, the Stars and Stripes, the new national emblem adopted by the American Congress on June 14, 1777, was recognized and saluted by a foreign power. For the remainder of the year 1778, while waiting for the Indien, Jones actively pursued, with unquestionable daring, his spectacular campaign against British shipping. In September he learned that he would not get the Indien and it was not until February 1779 that Louis XVI gave him command of an old East Indiaman, the Duc de Duras. Jones immediately went to Lorient where he ardently set about equipping his ship. In fact, Louis XVI could be said to be the real owner responsible for outfitting the ship, since he was to a large extent paying for the undertaking out of his own purse. Le Ray de Chaumont was the King's adviser and agent in Lorient, and Jones was frequently at odds with him, and also with the "Commissaire" of the Port of Lorient. When Jones stood out to sea on August 14, 1779, flying American colors, he was at the head of a small squadron. He had personally taken command of the Duras which he had renamed Bonhomme Richard in honor of Benjamin Franklin. Sailing with him were another American warship, the Alliance, and five French privateersmen: Pallas, Vengeance, Cerf, Granville and Monsieur. The last three soon left the formation. After having made several prizes, Jones engaged, on September 23, off Flamborough Head, two ships of the British Navy, the frigate Serapis and the corvette Countess of Scarborough. During the ensuing battle, which was waged with fury by both sides, the Bonhomme Richard was virtually alone. The Alliance was the only accompanying ship that sailed in close enough to take part in the combat, and her fire did rather more damage to the Bonhomme Richard than to the Serapis. Jones literally fought his gallant old ship to death. Just before the Bonhomme Richard had to be abandoned, Jones and his boarding party gained control of the Serapis, transferred the American crew, colors and signal codes on board her, and Jones then took command of his prize. A few hours later, the Bonhomme Richard foundered.

Anxious to get his prizes to safety, Jones took them in to Texel, where he arrived on October 3, 1779. He found himself suddenly famous. The toast of the town in Amsterdam, in Paris he became the darling of high society; he was acclaimed at the Op�ra; Parisian salons opened their doors to him as did the Masonic Lodge of the Nine Sisters. King Louis XVI awarded him a gold sword and made him a knight of the Order of Military Merit.

Return to page directory.

|

1780 - A Year of Movement.

Thus it was that the year 1780 began under better auspices than the previous year. The Navy, however, was confronted with a very serious problem: the lack of manpower. It was impossible to replace the sailors from Orvilliers' fleet who had succumbed during the epidemic. Also the news from Spain was not good. The British Admiral Rodney had succeeded in getting supplies to Gibraltar; he had also taken several prizes and had destroyed nine Spanish vessels commanded by Admiral Don Juan de Langara. Under full sail, Rodney then set course for the Antilles where the British Navy had taken an offensive stand, notably by preventing supplies from getting through to the French islands.

Realizing the dangers inherent in this situation, the French Navy fitted out a fleet at Brest and entrusted the command to Admiral de Guichen. Guichen, obliged to weigh anchor with reduced complements on most of his ships, arrived in Martinique on March 23, 1780 where he joined the division of De Grasse. The division under the command of LamottePicquet had been ordered to St. Domingue a few days earlier. Rodney too had only recently arrived in the West Indies, where he joined forces with Admiral Hyde Parker, already in those waters with a fleet of 17 vessels. There were several engagements between the two fleets, especially on April 17 and May 15 and 19, in which the advantage tended to remain with the French. These encounters could hardly be called victories, however. In June, the Spanish Admiral Don Solano arrived at Fort Royal, Martinique, with a fleet of 12 ships and a large convoy carrying war supplies and 10,500 soldiers. His crews were so weakened by disease that he decided to go straight to Puerto Rico and then on to Havana without attempting to engage the enemy.

In August, Guichen received orders to return to Europe and Rodney, who learned of this immediately, dispatched ten of his ships to Jamaica and sailed with the others to New York.

The action then moved to North America.

Return to page directory.

|

Rochambeau Lands in America.

At times, the patriots despaired of ever achieving their independence. They had been fighting for five years, and victory was still not in sight. In France, however, the failure of the invasion of Great Britain left several regiments of troops available for service elsewhere. Having therefore at hand the means of implementing a new policy, the Court of Louis XVI let itself be persuaded of the necessity of sending an

|

Chevalier de Ternay

| expeditionary corps to America. On May 2, 17 80 Admiral de Ternay, in command of a division of seven ships, sailed from Brest. The ships of the line Due de Bourgogne (90 guns), Neptune (74 guns), Conqu�rant (74 guns), Provence (64 guns), Eveill� (64 guns), Jason (64 guns) and Ardent (64 guns), together with the frigates Surveillante and Amazone and 30 transports, carried a total of 6,000 men under the command of Lieutenant General de Rochambeau. Ternay's orders specified Rhode Island as his destination unless he found the island to be already occupied by the British. He arrived on July 12, after having had a skirmish off the Bermuda Islands with a British naval division under Cornwallis. Rhode Island was in fact held by the Americans and Rochambeau's army immediately disembarked at Newport. Its presence on American soil signified the beginning of the end of the War for American Independence. In Europe, too, clouds were building up on the English horizon. The Netherlands had declared war against Great Britain and the League of Armed Neutrality of north European powers was not only about to strike a damaging blow to British foreign trade, which had already been seriously affected, but also to cut the supply route of naval stores that were indispensable to British shipyards. Britain was menaced in Europe and America alike, but in early 1781 its chances to win were still intact; the end of that critical year was, however, to see its defeat and the subsequent loss of its Atlantic seaboard colonies.

It is to be noted that Rodney began the year with bold action in the West Indies. Having received authorization in January to attack Dutch possessions, he took in succession: St. Eustatius, St. Martin, Saba, Demerara, Essequibo and Berbice as well as the French island of St. Barth�lemv. St. Eustatius, which was the trading center of the entire region and the main entrepot for goods from everywhere, was a great prize for the British, reported to have been worth a total of 75 million francs.

Return to page directory.

|

1781 - The Decisive Year.

On March 22, 1781 Lieutenant General de Grasse, the Ville de Paris flying his standard, left Brest with 26 ships of the line and four frigates. On the 29th one of the frigates, the Concorde, took leave of the fleet and set a direct course for Rhode Island; on board was

|

Comte d'Grasse

| Count de Barras de Saint Laurent, successor to Ternay who had died of exhaustion at Newport on December 15, 1780 after having fortified French positions there and organized their defense. When the fleet reached the Azores, Captain de Suffren, with five ships and a frigate, headed for the Cape of Good Hope and the Indian Ocean. On April 5 the Sagittaire, carrying ammunition and 600 soldiers for Rochambeau's army, was also detached from the fleet and ordered directly to Boston. On April 28, after 37 days at sea, the fleet and its convoy were within sight of Martinique. This rapid crossing was due to De Grasse's decision to have the slowest transports and merchant ships towed. The flagship Ville de Paris had set the example by taking a ship in tow.

Count de Grasse ran the blockade of Fort Royal, Martinique, that Hood had maintained for over 40 days, brought his convoy into port safely and then gave pursuit to the British ships which, despite a sharp encounter, were able to escape.

While different operations were being undertaken in the Caribbean area, De Grasse contacted Rochambeau and Washington. In those days of slow communications, small messenger ships, light and rapid, were used to permit consultation during the elaboration of campaign plans. They shuttled from the American forces to the army of Rochambeau on Rhode Island to De Grasse's fleet in Martinique and later in St. Domingue, and back again, over and over again. Each of the allied commanders wanted to strike the decisive blow, but agreeing on how and where to strike was not an easy matter.

General Washington, at the head of the main American Army, was in Connecticut, not far from Rochambeau in Newport. The two generals met at Wethersfield, Connecticut, for a series of discussions. Washington advocated attacking New York because of its proximity and its strategic location between the North and the South, despite the fact that it was strongly held by the British.

Return to page directory.

|

De Grasse Chooses the Chesapeake.

At the same time, however, the mobile hit-and-run operations conducted in the South by British General Lord Cornwallis and by his adversaries, the Marquis de La Fayette and other American generals, were taking a turn which meant that a combined attack in Virginia could lead to decisive victory. In fact, after this campaign which had been brilliant for him but disastrous for the patriots, Cornwallis rapidly withdrew across Virginia, under constant harassment by the Americans, especially those under La Fayette's command, and took refuge in the stronghold on the York River whence he hoped to be evacuated by sea to New York. Rochambeau, well aware of what could be gained from Cornwallis' situation, favored striking an essentially strategic blow in Virginia destined to destroy enemy resistance. The final decision was left to De Grasse, however, who chose Chesapeake Bay because, in addition to the above considerations, the journey there and back to the French West Indies was shorter than going to New York. This reduced the possibility of attack by the English and also, above all, that of being caught up in the violent windstorms which regularly sweep the area between the West Indies and the southern coast of North America at the time of the equinox. De Grasse in fact felt it was already too late in the season for operations north of the Chesapeake. The decision was therefore made; the allied offensive would be launched against Cornwallis' army in Virginia. At Washington's and Rochambeau's requests, De Grasse undertook to collect funds which were badly needed on the continent. Unable to raise a significant amount in St. Domingue � in spite of the example he set by mortgaging his own lands � De Grasse sent the frigate Aigrette to Cuba. The Spanish authorities there, aided by Havana merchants and by noble ladies [?*] of the island who donated their diamonds [??], were able to create a war fund of 1,200,000 pounds (probably livres tournois) in the space of five hours! The Aigrette, under full sail, rejoined the fleet at the entrance to the Bahama Channel.

Meanwhile, at Cap Fran�ais, on the northern shore of St. Domingue, Admiral de Grasse had taken his fleet out to sea in all haste. To avoid being delayed by a convoy, he had embarked the landing troops on board his 28 ships. These troops included detachments from the local colonial regiments and from the G�tinais, Agenais and Touraine regiments which had been held in reserve at St. Domingue under the command of the Marquis de Saint Simon (3,000 infantrymen, l00 artillerymen and l00 dragoons). He also took on ten field cannons and several siege guns. The French fleet arrived at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay on August 30 carrying a total of 5,000 men (including ships' crews) and the 1,200,000 livres requested by Rochambeau.

At the beginning of July, Washington and Rochambeau, who knew De Grasse was in the Antilles but had not yet been informed of the objective he had chosen for their combined operations, moved southward with their armies, in the direction of New York as if they planned to attack it. On August 14, informed that De Grasse was approaching Chesapeake Bay for a decisive strike there, the two generals left a few troops near New York to keep the enemy in doubt as to their campaign plans, and began a forced march to Virginia. General Washington was in Chester, Pennsylvania, on September 5 when he learned that the French fleet had arrived in the bay. Rochambeau, coming from Philadelphia, joined forces with Washington in Chester just as the latter received the good news, and had the surprise of seeing Washington, usually so reserved, running to meet him gesticulating enthusiastically with his hat in one hand and a white handkerchief in the other, his face radiant, joyful and suddenly much younger. He embraced Rochambeau, exclaiming, "He's here! He's arrived!"

That same day � September 5 � De Grasse's fleet was engaging the English fleet off Cape Henry in what was to be a battle of vital importance.

De Grasse had arrived six days earlier with, he felt, no more than six weeks to spend in American waters. His first concern had been to establish contact with Rochambeau, Barras, La Fayette, La Luzerne, who was then French Minister in Philadelphia, and with Washington. He then put Saint Simon's troops ashore. He advocated making an immediate attack on the fort at Yorktown, where Cornwallis was entrenched, and felt sure that La Fayette's and Saint Simon's forces along with those of the fleet would be sufficient for the task. Young La Fayette found himself in the unexpected position of having to dampen the enthusiasm of a 59-year-old man! He succeeded in doing so by convincing De Grasse of the advantages of a victory so complete that it would determine the outcome of the war, and of the need to assemble, to this end, all available allied land and naval forces. It was therefore necessary to await the arrival of Washington's and Rochambeau's armies. De Grasse recognized the soundness of this point of view and wrote to inform Washington so on September 2:

"I have suspended my plans until the arrival of generals whose experience in the conduct of war, knowledge of the country and intelligence will greatly strengthen our means. I am sure that my army, which was only eager to demonstrate its courage, will surpass itself under the eyes of generals who are able to appreciate it."

At the same time La Fayette was urging Washington to make haste, and General du Portail, assigned to De Grasse by Rochambeau, wrote his commander: "Dear General, come with the greatest expedition, not because we wish to take York without you . . . but . . ." In fact, this was precisely what Du Portail feared!

Return to page directory.

|

The Chesapeake, the Battle off the Virginia Capes.

In any case De Grasse was soon to find himself very busy, and in his own element: at sea. When a task force was sighted at i0 o'clock on the morning of September 5 approaching from the north, everyone thought it was Barras coming from Newport. The mistake was quickly realized. It was an English fleet with 19 ships of the line, one 50-gun ship, six frigates and a fire ship. Admirals Graves and Hood had been sent from New York to Yorktown by General Clinton to break the blockade and evacuate Cornwallis. Although some fleet personnel was on shore, and in spite of the fact that not all of Saint Simon's troops had been disembarked, De Grasse did not hesitate. He decided to attack the English in the open sea beyond Cape Henry since by staying inside the bay on the defensive he would be certain to deliver Barras' task force, which was expected to arrive any day, right into the hands of the enemy. He was able to call a part of his personnel back on board while making haste to sail with the first tide. The ships cleared the Capes, the swiftest in the lead, and went into battle formation in the order of their arrival. Though the French had superior fire power (1,794 cannons versus 1,410 for the English), the English had the advantage of the wind. Heavy fighting began and continued until nightfall. The British, having suffered much more damage than the French, spent all of the next day making repairs. The French fleet needed nearly the whole of that day to maneuver to windward of the British and take up battle positions for the following day. September 7 dawned, but the British, still out of reach of French guns, succeeded in maintaining their distance, and on the 8th they escaped, every stitch of canvas spread. On the 9th, there being no trace of the English, De Grasse reentered the bay where he found Barras' ships, which had arrived in the meantime, riding quietly at anchor.

Graves and Hood had had 336 casualties. All their ships had been damaged, three of them being incapacitated for further fighting: one of these, the Terrible, was unable to reach New York and had to be burned at sea.

Two of De Grasse's ships were damaged but were repaired on the spot. There were 240 French casualties.

The fate of Yorktown was already cast: De Grasse's fleet had control of the coast and the bay; its forces were intact and even considerably augmented since the enemy fleet had been lured into the trap laid by De Grasse and drawn away from the bay to allow Barras to arrive without difficulty. The English, defeated and discontent, returned to New York in confusion and bitterness. Yorktown could now be taken at the convenience of the allies without Cornwallis having the slightest chance of escaping with his men.

Thus assembled in Chesapeake Bay, the French naval forces in North America, while keeping a watchful eye out for an unlikely enemy attack by sea, participated fully in the siege and capture of Yorktown. Barras unloaded the heavy siege guns he had brought with him from Newport. Ships with shallow drafts were sent either to Elk's Head in the upper part of the bay to embark Washington's troops or to Annapolis, where Rochambeau's army was encamped.

Lord Cornwallis had 9,000 men occupying the narrow spit of land between the York and James Rivers at the point where they flow into Chesapeake Bay. His headquarters were at the key fortress at Yorktown. On the opposite bank of the York River he also held the village of Gloucester, and thus could bring the mouth of the York River under his crossfire.

While the allied armies were taking position around Yorktown, General Washington went on board the Ville de Paris to meet De Grasse for the first time. Washington was accompanied by General de Rochambeau, General de La Fayette, General Knox, Governor Benjamin Harrison and Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton. The fleet's ships were of course dressed over all, and gave Washington a 13-gun salute as he came aboard. As soon as the Commander in Chief arrived on deck, De Grasse rushed to him, threw his arms around him and kissed him on both cheeks, saying over and over again with obvious emotion: "My dear little general!" While De Grasse stood 6' 4", Washington was 6' 6" [?*] and in any case cut such an imposing figure that the words "dear little general" provoked quickly stifled hilarity among the onlookers. After an excellent luncheon on board, the commanders sat down to a conference. De Grasse finally agreed to prolong his stay in American waters until November 1, to the immense satisfaction of the generals, and plans were adopted for the final stage of the siege.

Return to page directory.

|

The Siege of Yorktown.

All around Yorktown were positioned the allied armies numbering 7,000 French soldiers and 9,000 Americans, 3,500 of them militiamen. These figures did not include French naval personnel.

The siege was conducted according to training manual rules. The engineerswho were virtually all French, even those in the American army-the artillerymen and the sappers all carried out their appointed tasks without haste and without leaving anything to chance. The British outposts fell one by one. Preparations were begun for the final assault and De Grasse, somewhat reluctantly, detailed the Experiment, commanded by Captain de Martelli-Chautard, and the Vaillant to block the York River upstream from Yorktown. While passing through crossfire from Yorktown and Gloucester did not appear to bother him in the least, he did not like exposing his ships to attack from English fire ships or to the dangers of a river mooring. He finally agreed to it, however, and Martelli was put in charge of the upriver blockade. The attack on the main fort began on October 9; on October 11 Cornwallis wrote to his chief, Clinton, in New York that only a powerful naval operation could save him. But he well knew he could no longer count on such an intervention. On October 17 Cornwallis asked for a truce in order to prepare surrender terms. This was granted and the act was signed on October 19.

Return to page directory.

|

The Surrender of Lord Cornwallis.

The ceremony of surrender was solemn and grandiose. Every detail had been decided in advance. The French forces and the American Army formed two parallel lines one mile long, facing each other. General Washington took the head of the American line; General Count de Rochambeau was at the head of the French; each commander was surrounded by his staff. Only one major figure was absent: Lord Cornwallis. He was reported to be ill and perhaps he was. Rochambeau had left his sickbed to attend the ceremony while De Grasse, who was too ill to come ashore, had delegated Barras to represent him. Cornwallis had however given his sword to General O'Hara to be surrendered to the victors. O'Hara started toward Rochambeau as if to give him the sword but Count de Dumas, placing himself in front of Rochambeau, intimated to the British general that the sword had to be given to the Commander in Chief, General Washington. This was the first unexpected event of the day. Washington then designated General Lincoln to receive the sword, as he had had to surrender his own sword to Cornwallis at Charleston. Lincoln took it in his hands, kept it a few moments, then returned it to General O'Hara as a tribute to the courage of the English and to show that the Americans were generous in victory.

The second unexpected event of the day then occurred. The surrender agreement stipulated that Cornwallis' soldiers should leave the fort in formation with their flags furled; their band was to play as they marched to a field lined with French hussars where they were to lay down their arms. They did so, many in tears; but they accorded themselves a small measure of satisfaction in the form of British humor that bordered on the impertinent: the march they had chosen for this occasion was entitled "The World Turned Upside Down"

Although the world was "upside down" for the British, it was a joyful day for the American and French allies, a glorious day, crowning as it did so many years of efforts, of sacrifice and of hope.

The allies had reason to rejoice. The English had surrendered 6,500 regular troops, 1,500 sailors, 2,000 black troops, 160 pieces of artillery, 70 cast-iron cannons, 8 mortars, and 40 transports to the Americans. Twenty transports had been sunk and 15 ships burned, including one 50-gun ship and two corvettes. Twentytwo flags had been captured and 1,100 men killed, wounded or stricken with disease. These are the figures reported back to France at the time. As will be seen, they differ somewhat from those recorded on the Yorktown victory monument.

Allied losses had been astonishingly small: 88 killed (60 of them French) and 300 wounded (193 of them French).

Return to page directory.

|

1782 � The War Moves to the Lesser Antilles.

The victory at Yorktown was indeed that of the independence of the United States. Peace terms still had to be negotiated, but on the North American continent guns fell silent, except when Spanish and French forces captured the city of Pensacola and western Florida, which had remained British until then. Elsewhere, however, the war between England and France continued. Hood and De Grasse both returned to the West Indies. The islands of St. Eustatius, St. Martin, Saba, St. Kitts, Nevis and Montserrat were taken by the French fleet, in most cases backed by troops under the command of Marquis de Bouill�, and the Spanish and French chiefs of staff began preparing an attack against Jamaica. However, the sudden reappearance of Admiral Rodney with 17 ships radically altered subsequent events -not only in the Caribbean but elsewhere, too-and thus the whole outcome of the war. Having joined forces with Hood, Rodney proceeded to blockade Martinique. De Grasse thus found himself obliged to escort a large convoy to St. Domingue with a fleet inferior to that of the enemy. The convoy got under sail on April 8, 1782, escorted by the Experiment and the Sagittaire and the frigates Railleuse, Engageante and Richmond, followed a few hours later by De Grasse with 33 ships. On April 9 Rodney's 36 sail were sighted.

April 9 through 1 2 saw the two magnificent fleets fight a running engagement from Dominica to the Saintes islands. The English were the victors and the flagship Ville de Paris was forced to strike its colors to 10 English vessels which included the Barfieur flying Rodney's standard. De Grasse, who only a short time before had inflicted a decisive defeat on the British Navy, was taken prisoner and the Ville de Paris was towed to Jamaica. In addition to the flagship, three other French ships were captured: the Glorieux, the Hector and the Ardent, but none was to reach England. The Ville de Paris, the Glorieux and the Hector, together with two British ships, the Centaure and the Ramillies, went down at sea with all hands, and the Ardent, which was foundering when it had reached Jamaica, was judged beyond repair and scrapped.

Among the men who fell during the battle, one of the most able was probably Captain du Pavillon, flag-captain of the Marquis de

|

Comte de la P�rouse

| Vaudreuil on board the Triomphant. Ever since the end of the Seven Years' War, Du Pavillon had been developing, with the aid of Verdun de la Crenne, a code of signals for use at sea; this had carried naval communications a step forward and the code had been employed to great advantage throughout the War for American Independence.

The battle of the Saintes was viewed in France, especially in the Navy, as a disaster. Controversies flared up and the prestige as

well as the cohesion of the Navy's officer corps suffered a severe blow. In addition, the French and Spanish allies had failed in an attempt to drive the British out of Gibraltar. The best news in 1782 came from the Indian Ocean where the exploits of Suffren helped the people at home to forget the humiliation of defeat in the West Indies, and from Hudson Bay where a brilliant young captain, Count de la P�rouse, had destroyed English trading posts at the price of considerable effort. Without respite, however, the Navy, while continuing its routine operations in America and in other areas, began preparing, in conjunction with the Spanish Navy, a major offensive against Jamaica.

But 1783 was to be the year of peace.

Return to page directory.

|

|

* * * *

|

Summary

Although France, and in particular her Navy, had not attained all the goals she had set for herself, she had nonetheless fully achieved the principal objective, namely, the independence of the United States. She had won a major victory over her British rival, and at the same time had avenged the loss of Canada. In order to do so, she had made a tremendous effort to build up her Navy which, as a result, had been well prepared for this war. The 74gun warship had been developed to the point of near perfection; task forces were well trained; and the organization of logistic support for the colonies and for the fleets operating in distant waters had been greatly improved since preceding wars. French methods of recruitment, officer training, personnel administration and the fringe benefits of an early form of "social security" were superior to the English system. They gave France a certain advantage, at least at the beginning of a war. Yet the advantage was relative only in the case of the War of American Independence, because France too suffered from a shortage of manpower. Delays and errors of judgment occurred in the upper levels of command as well as at the ministerial level, especially during Sartine's administration (he was replaced in �780 by the Marquis de Castries). But all in all France fought this war, which in more ways than one changed the face of the world, in a determined, steadfast and competent manner. Moreover, she had never before had such a splendid navy or so many exceptional officers, among whom Bougainville, not yet cited in this brief account, deserves special mention.

Britain, weakened by the price paid for its victory in 1763 and at grips with a radically new situation-the revolt of its finest colonies-had faced serious problems in its systems of command and of logistics. Fortunately, it still had first-rate naval officers, and its ships had an important technical lead: copper-plated bottoms. British war vessels thus often had the advantage of speed over those of the French and could either escape from or overtake French ships almost at will. Britain also had the benefit of a deadly invention developed at the Carron ironworks in Scotland: the short cannon (mortar or howitzer) known as the carronade. The important role played by this ordnance in the fighting in the Lesser Antilles can almost be compared to that of the Gribeauval cannons in the victory at Yorktown after they had been transported by Barras' fleet from Newport to the Chesapeake.

France had come out of the war victorious, in spite of one cutting defeat, but with an empty treasury and confronted -with a very grave financial crisis. Shaken by bankruptcies and civil unrest, by a food crop failure followed by an exceptionally severe winter, monarchist France toppled over the brink of revolution. The last war fought by the France of the ancien r�gime, the War for American Independence, was also, in its ideology and its extension to different and widely separated parts of the world, the first war of "modern" times. Its repercussions on the future course of events were immeasurable. The world today would certainly be very different if that war had had any outcome other than Franco-American victory.

All those who visit the battlefield of Yorktown in this bicentennial period will readily understand that the victory won on that site was indeed that of France as well as that of the United States when they read the inscription on the memorial column erected there:

|

AT YORK ON OCTOBER 19 1781 AFTER A SIEGE OF NINETEEN DAYS

BY 5500 AMERICAN AND 7000 FRENCH TROOPS OF THE LINE 3500 VIRGINIA MILITIA

UNDER COMMAND OF GENERAL THOMAS NELSON AND 36 FRENCH SHIPS OF WAR

EARL CORNWALLIS COMMANDER OF THE BRITISH FORCES AT YORK

AND GLOUCESTER SURRENDERED HIS ARMY 7251 OFFICERS AND MEN

840 SEAMEN 244 CANNON AND 24 STANDARDS

TO HIS EXCELLENCY GEORGE WASHINGTON

COMMANDER IN CHIEF OF THE COMBINED FORCES OF AMERICA AND FRANCE

TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE COMTE DE ROCHAMBEAU

COMMANDING THE AUXILIARY TROOPS OF HIS MOST CHRISTIAN MAJESTY IN AMERICA

AND TO HIS EXCELLENCY THE COMTE DE GRASSE

COMMANDING IN CHIEF THE NAVAL ARMY OF FRANCE IN CHESAPEAKE

|

* * * * * * * * *

* * *

|

Ulane Bonnel (1918-2006) was born Ulane Zeeck in Lingleville, Texas. She received a commission in the U.S. Navy in 1943, and acquired the rank of lieutenant commander before departing the naval service in 1946. While working for the Congressional Research Service at the Library of Congress, specializing in military affairs, she met and married, in 1947, Paul-Henri Bonnel (1912-1984), an officer in the French Navy's medical corps then serving with the French naval mission in Washington, D.C..

Mme. Bonnel went to France with her husband, who became chief of the French Navy's maritime health service (chef du service sant� des gens de mer) in 1969-72, and later worked with the World Health Organization. Mme. Bonnel completed her doctoral thesis at the Sorbonne on �French and American privateering in the period between 1797 and 1815', including the 'Quasi-War with France' and the �War of 1812'. She played a major role developing professional connections between American and French naval historians and in founding both the scholarly journal Chronique d'histoire maritime in 1979, and the French Commission of Maritime History (Commission fran�aise d'histoire maritime) in 1980 � serving as president of the latter in 1986-1989.

In 1964, she was appointed the delegate in France for the Library of Congress and played an important role in cooperation between French and American naval historians in the period leading up to the bicentenary of the United States. She coordinated the photocopying of documents from French archives for the Library of Congress and the U.S. Navy's Naval Historical Center, relating to the key role that the French Navy played in obtaining American Independence in 1778-1783. Many of the documents she acquired were translated to enrich the U.S. Navy's multi volume series on Naval Documents of the American Revolution, begun by William Bell Clark and William J. Morgan (historian).

In recognition of her great contributions to Franco-American historical relations, she was elected the first woman member of the History, Letters, and Arts section of the Acad�mie de Marine. She also served as president of the Association internationale des Docteurs des Universit�s fran�aises and vice-president of the Institut Napol�on. After the 1984 discovery of the wreck of CSS Alabama, sunk in Cherbourg harbor during the American Civil War, she helped to organize both the French and American branches of the �CSS Alabama Association', serving as president of the French branch and helping to develop support for its work in underwater archeology on the site of the wreck. In this role, she was the key person working to negotiate the international agreement between France and the United States over the wreck and the wreck site in French waters.

Published Works: La France, les �tats-Unis et la guerre de course (1797-1815) (1961); West Texas: the Z ranch or the story of the Zeeburgs (1970); Under the ice cap (1970); Sainte-H�l�ne, terre d'exil (1971); Guide des sources de l'histoire des �tats-Unis dans les archives fran�aises with Madeline Astorquia�and others (1976); and editor of Fleurieu et la marine de son temps, colloque organis� par la Commission fran�aise d'histoire maritime, edited by Ulane Bonnel (1992).

[Foregoing text was partly extracted from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulane_Bonnel]

|

Return to page directory.

Return to top of this page.

Return to webpage on

French Naval Leaders and the French Navy in the American War for Indepenence.

Page posted 23 October 2004; revised 12 August 2007.

|

Far from being able to send out anything near the reported figure of 142 ships of the line, Britain had from 60 to 65 more or less ready for action, whereas France could count on roughly 50. In the peak years of the war, Great Britain was to reach the quite extraordinary total of from 90 to 95 ships of the line as compared to 65 to 70 for France. Their comparison reveals the crucial importance, at least in theory, of the 50 to 55 Spanish ships of the line which, if added to those of France, should have given an overwhelming advantage over the British Royal Navy. It is interesting to note that, according to French naval sources, the total number of warships of the three navies, including transports and supply vessels, reflects the same general proportions: France 211; Spain: 144; Great Britain: 311.

Far from being able to send out anything near the reported figure of 142 ships of the line, Britain had from 60 to 65 more or less ready for action, whereas France could count on roughly 50. In the peak years of the war, Great Britain was to reach the quite extraordinary total of from 90 to 95 ships of the line as compared to 65 to 70 for France. Their comparison reveals the crucial importance, at least in theory, of the 50 to 55 Spanish ships of the line which, if added to those of France, should have given an overwhelming advantage over the British Royal Navy. It is interesting to note that, according to French naval sources, the total number of warships of the three navies, including transports and supply vessels, reflects the same general proportions: France 211; Spain: 144; Great Britain: 311.