SECOND NAVAL BATTLE

OF THE

VIRGINIA CAPES (1781)

|

The epic 5-9 September 1781 "Battle of the Virginia Capes" is probably the most well known naval engagement of the American Revolution, largely due to its significant contribution to the success of the Yorktown Campaign, the crowning military victory in the War for American Independence. The battle saw the Admiral de Grasse's 24 French ships of the line drive off the 19 British ships under Admiral Graves , thus isolating the British forces of Cornwallis at Yorktown. However, it was really the Second Battle of the Virginia Capes in that year.

There had been an earlier 'Battle of the Virginia Capes'. On 16 March 1781, a French squadron under Destouches fought a British squadron under Arbuthnot for about an hour. Though the British received the worst in the exchange, the French admiral did not push to break the British blockade of the entrance to the Chesapeake. The result was nearly the opposite of the September 1781 battle covered on this webpage. Arbuthnot managed to keep open a line of communications to Arnold's British land army, conducting a campaign of devastation in Virginia. Destouches' failure to land about 1,200 troops compromised the efforts of an American force, commanded by Lafayette, that marched into Virginia in April of that year. The British were able to reinforce in Virginia with troops under General Phillips, who assumed British command in the theater until Cornwallis arrived. Links to webpages on the Yorktown Campaign, the First Naval Battle of the Virginia Capes are at the bottom of this webpage.

|

|

|

The above painting ' Combat de le la Chesapeak' is byTh�odore Gudin's and is held by the Mus�e de Versailles. The French fleet is depicted to the left, with Bougainville's Auguste, flying a blue ensign at the forepeak and next to the right is the gun smoke clouded Ville de Paris, De Grasse's three-decker flagship. The British formation is shown on the right. The painting incorrectly depicts the two fleets as crossing one another's course; whereas they generally were in parallel lines to one another when exchanging cannon fire.

|

|

Text on this page is taken, with minor editing, from Part XV, "THE SEA BATTLE OFF THE CAPES OF VIRGINIA DE GRASSE-GRAVES"

of Colonel H.L. Landers' The Virginia Campaign and the Blockade and Siege of Yorktown 1781 (US Printing Office, Washington, 1931).

|

|

|

The French Fleet had made an unusually quick passage across the Atlantic, taking only 38 days to sail from Brest to the Windward Islands. Arriving off Martinique on the 29th of April, De Grasse found the part blockaded by a British fleet of 18 ships under Rear Admiral Sir Samuel Hood. A light action ensued, but Hood refused to become seriously engaged with a fleet of such superior strength and withdrew. De Grasse pursued for some distance without being able to bring on a general engagement and finally returned to Fort Royal. The French Fleet spent two days in the harbour and then moved against the port of Tobago, which surrendered on the 2d of June. From Tobago the fleet proceeded some days later to Santo Domingo with a convoy of 200 sail of merchantmen collected at Grenada, Martinique, and

Guadeloupe, and on the 16th of July arrived at Cape Francais. Awaiting the fleet at the cape were the dispatches from America, in which Washington and Rochambeau had stated the urgent need for early cooperation by the admiral either at New York or in the Chesapeake. De Grasse replied to these dispatches an the 28th of the month, this being the letter which De Barras received at Newport, and from

which extracts came to Washington's hand on the 14th of August.

I have seen with regret the distress, which prevails on the continent, and the necessity of the prompt succours you solicit. I have conferred with M. de Lillancourt, who took command of the government here on the day of my arrival, and engaged him to furnish from the garrison of St. Domingo a detachment from the regiments of Gatinois, Agenois, and Tourraine, amounting in all to three thousand men, one hundred artillery, one hundred dragoons, ten pieces of field

De

Grasse.

ordnance, and several of siege artillery and mortars. The whole will be embarked in vessels of war, from twenty-five to twenty-nine in number, which will depart from this colony on the 3d of August, and proceed directly to the Chesapeake Bay, which place seems to be indicated by yourself, General Washington, M. de la Luzerne, and Comte de Barras, as the best point of operation for accomplishing the object proposed.

I have likewise done all in my power to procure for you the sum of twelve hundred thousand livres, which you say is absolutely necessary. This colony is not in a condition to afford you such a supply; but I shall obtain it from Havana, whither a frigate will be sent for the purpose, and you may depend on receiving that amount.

As neither myself, nor the troops commanded by the

Marquis de St. Simon, can remain on the continent after the 15th of October, I shall be greatly obliged to you if you will employ me promptly and effectually within that time, whether against the maritime or land forces of our enemy. It will not be possible for me to leave the troops with you beyond that period; first, because part of them are under the orders of the Spanish generals, and have been obtained only on the promise that they shall be returned by the time they will be wanted; and, secondly, because the other part are destined to the

garrison of St. Domingo, and cannot be spared from that duty by M. de Lillancourt. The entire expedition, in regard to these troops, has been

concerted only in consequence of your request, without even the previous knowledge of the ministers of France and Spain. I have thought myself authorized to assume this responsibility for the common cause; but I should not dare so far to change the plans they have adopted, as to remove so considerable a body of troops.

You clearly perceive the necessity of making the best use of the time, that will remain for action. I hope the frigate, which takes this letter, will have such dispatch, that everything may be got in readiness by the time of my arrival, and that we may proceed immediately to fulfil the designs in view, the success of which I ardently desire.

The information contained in this dispatch about the fleet proceeding to the Chesapeake Bay was of great importance; but of even more vital concern was the statement that the troops borrowed from the West Indies garrison could not remain on the continent after October 15, thereby making it necessary to begin capital operations immediately upon the arrival of De Grasse in Virginia.

The fleet sailed from Cape Francais on the 5th of August, 1781. The ships were conducted by Spanish pilots through the Old Bahama Straits, where they were joined by the frigate which had been dispatched to Habana for the money promised by De Grasse. Upon approaching the capes of Virginia on the 29th of the month, the frigates Glorieux, Aigrette, and Diligente, chasing in the van, discovered the British frigate Guadaloupe and the corvette Loyalist anchored off Cape Henry, and pursued them to the mouth of York River, where the corvette was taken. [Ed Note: Lander's original text had de Grasse approaching the capes as the 30th, which was actually the day the French fleet fully entered the Chaseapeake Bay and probably even anchored in Lynnhaven Roads. However, de Grasse does not prepare his dispatch announcing his arrival to Lafayette until 31August.]

The Glorieux and two frigates anchored at the mouth of the York to blockade the river, and the next day the Vaillant and Triton engaged in the same duty. The Experiment, Andromaque, and several corvettes were stationed in

the James River to prevent passage by the British Army should it attempt to retreat into the Carolinas. When the fleet came to anchor on the 30th Colonel Gimat, whom Lafayette had posted at Cape Henry with dispatches for De Grasse, went aboard the flagship Ville de Paris.

The joy that filled Lafayette when he learned of the arrival of the French Fleet in the inland waters of the United States can well be imagined. His first thought was to send the glorious news to his beloved chief and friend. In a letter to General Washington written by him

on the 1st of September from his camp at Holt's Forge, he said:

From the bottom of my heart I congratulate you upon the arrival of the French fleet.

The marquis now awaited with the greatest impatience the arrival in Virginia of the allied armies and the earlier appearance of the Commander in Chief. The glory of victory would soon be attained by the man to whom the country had given its trust for six years, and

it was Lafayette's great desire that nothing be done which might place the laurels upon another's head. He was tempted, but he was too good a soldier not to realize the un wisdom of the suggestion made to him. "It appears Comte de Grasse is in a great hurry to return," he wrote to Washington, "he makes it a point to put upon my expressions such constructions as may favour his plan." Lafayette could not agree with De Grasse as to the necessity for haste, for he felt that "having so sure a game to play, it would be madness, by the risk of an attack, to give any thing to chance." This wise decision met with the warm approval of General Duportail, who arrived on the flagship the morning of the 2d as an emissary from Washington and Rochambeau. After learning of the desire of the admiral for immediate action against the British Army, and of Lafayette's stand, Duportail wrote to Rochambeau an the matter.

Our young general's judgment is mature; with all the ardor of his temperament, I think he will be able to wait for the proper moment and not touch the fruit until it is ripe.

On the 2d of September the detachment of 3,200 men under M. de St. Simon was put aboard boats and sloops and transported from the anchorage of the fleet in Lynnhaven Roads to Jamestown, where they were landed the same day. De Grasse sent a letter to Washington at

this time giving information that he had the York River blockaded at its mouth and the James River guarded. With the rest of his command he was at Cape Henry �

ready to engage the enemy's maritime forces, should they come to the relief of Lord Cornwallis, whom I regard as blockaded until the arrival of Your Excellency and of your army.

The contents of the dispatches from Washington and Rochambeau and the information derived from their bearer, Duportail, caused De Grasse to accept gracefully the postponement of operations, and he made no further attempt to induce Lafayette to lead his own and St.

Simon's army against the British position at Yorktown.

* * * * * * *

The British sloop Hornet arrived at Sandy Hook on the 19th of July, bearing dispatches from the Admiralty dated the 22d of May. The most important piece of intelligence contained in the dispatches was that Colonel Laurens would sail for America before the end of

June with money, clothing, and military stores, in a convoy of merchantmen escorted by one ship of the line, another armed en flute, and two frigates. The admiralty advised Graves that the British Government felt a most serious blow would be struck if the colonies were deprived of these essential succours, and gave orders to the commander of the North American fleet to keep a sharp lookout for the convoy and to

determine upon the most likely places to station cruisers for the purpose of intercepting it.

The Admiral decided that the views of government were so pressing as to require him to go to sea at once with his squadron. The fleet of De Barras, then at Newport, might be encountered, but that chance must necessarily be taken. Should the French fleet in the West

Indies attempt to reach New York or the Chesapeake during his absence, he could rightfully expect that Rodney would handle the situation. In order to keep himself informed of conditions along the coast, he made judicious arrangements for his lighter vessels to engage in reconnaissance. The frigate Solebay was to cruise from the Navesink to Cape May. The frigates Medea, Richmond, and Iris were stationed of the Delaware. The frigates Charon, Guadaloupe, and Fowey, and the sloops

Bonetta and Loyalist were in the Chesapeake. Three coppered ships were ordered to Charleston to cruise alternately in search of the expected enemy.

These arrangements having been made, Graves crossed the bar at Sandy Hook on the 21st of July with 6 sail of the line and the next day was joined by the Adamant of 50 guns. While cruising off St. Georges Bank on the 28th of the month the Royal Oak,

which was returning from Halifax to New York, joined the squadron. With a command of eight ships Graves felt no further reluctance to engage M. de Barras, should the French Fleet sail from Rhode Island.

On the 27th of July the British sloop Swallow arrived at New York from the Windward Islands with dispatches from Sir George Rodney. The admiral's letter, dated aboard the Sandwich, Barbados, 7th of July, and addressed to Admiral Arbuthnot, gave

information that a French fleet of 28 sail of the line was at Martinique, a part of which was destined for North America. Admiral Rodney said in the letter:

In case of my sending a squadron to North America, I shall order it to make the Capes of Virginia, and proceed along the coast to the Capes of the Delaware, and from thence to Sandy Hook, unless the intelligence it may receive from you should induce it to act otherwise.

The British commodore left in command at New York ordered the captain of the Swallow to carry Rodney's dispatches to Admiral Graves, then cruising of Boston Harbour. Unfortunately for the British the sloop engaged in an attack upon a privateer and was in turn attacked on the 16th of August by 4 privateers and pushed on shore upon Long

Island, 11 leagues to the eastward of Sandy Hook.

Because of intense fogs of St. Georges Bank, which rendered it impossible for Admiral Graves to carry out his mission, the British squadron returned to Sandy Hook on the 18th and came up to New York. There Graves learned of the intelligence sent by Rodney, but owing to the need of repairs he could not go to sea until three of his ships were overhauled. The Robust and Prudent were ordered to the dockyard in East River. The Europe was brought close into the shore, lightened, and

heeled in order to repair her sheathing and stop leaks.

Prior to going to sea in search of Colonel Laurens, Admiral Graves had discussed with General Clinton the matter of attacking the French post at Newport, now that the land defenses were so weakly held, and upon the return of the British squadron to New York further

consideration was given to this enterprise. It was now decided that as soon as the Robust and Prudent were repaired joint operations would be undertaken against this station. Before the work was accomplished, however, Rear Admiral Hood arrived with the greater part of the West Indies fleet and an the 28th of August anchored outside the bar off Sandy Hook. Hood's command consisted

of 14 sail of the line, 4 frigates, 1 sloop, and a fire ship.

Owing to the desire of Sir George Rodney to return home on account of poor health, he had given up command of His Majesty's fleet at the Leeward Islands to Sir Samuel Hood and on the 1st of August had sailed for England. Prior to relinquishing command, Rodney prepared

comprehensive instructions dated July 24 for the use of the fleet along the Atlantic coast, after first providing protection for a valuable outward-bound convoy of merchantmen to

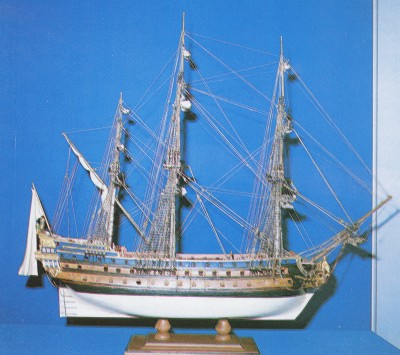

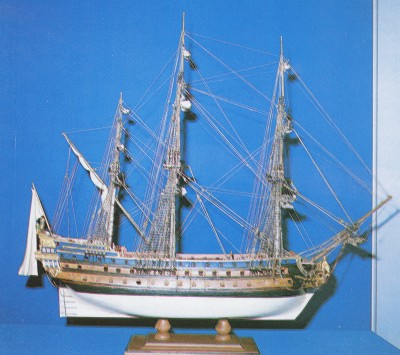

Ville de Paris, Flagship of De Grasse. Model in the Hampton Rhodes Museum, Norfolk, Virginia.

Jamaica. Hood was directed to make his way toward the coast of North America, after seeing the convoy safe, and there employ his ships in such manner, should he be the senior officer on that station --

as shall seem to you most conducive to his Majesty's Service, by supporting his Majesty's liege Subjects and annoying his rebellious ones, and in Counteracting such Schemes as it may be reasonable to conclude are formed for the junction of the French Fleet

from Cape Francois with that already there, or with the Forces of the Rebels in America. Having lately sent an Express to Admiral Arbuthnot or the commanding Officer on that Station by the Swallow, that the ships I might either bring or send from hence would endeavour first to make the Capes of the Chesapeake, then those of the Delaware, and so on to Sandy Hook, unless Intelligence received from his Cruizers (whom I desired might be looking out off the first Capes or Elsewhere) should induce a contrary Conduct; I think it necessary to acquaint

you therewith, and to direct your sailing in Conformity thereto, unless Circumstances you may become acquainted with as you range along the Coast, should render it improper; which Service, although not only your general Experience and Skill as an Officer, but your particular knowledge of that Station, I make no Doubt will enable you with Reputation and Effect to perform.

On the 25th of August the British Fleet made the land a little to the southward of Cape Henry and, finding that no enemy had appeared either in the Chesapeake or Delaware, proceeded off Sandy Hook. Foreseeing that great delay and inconvenience might arise from going

within the Hook, Hood anchored outside. He then got into his boat and met Clinton and Graves on Long Island, where they were deliberating upon a plan to destroy the ships at Newport. As there was great necessity for immediate action by the combined fleet, either to attend Clinton to Rhode Island or to look for the fleet of De Grasse at sea, Hood urged Graves to come outside the bar with such ships of his squadron as were ready, before the approaching equinox should render the crossing of the bar dangerous. Graves readily accepted the suggestion and said his ships would be sent out the next day.

That evening intelligence was brought of M. de Barras having sailed on the 25th of the month with his whole squadron. Graves immediately determined to proceed with the two squadrons to the southward, with the hope of intercepting either Barras or De Grasse, or if possible of engaging both of them. It was not until the 31st, however, that the wind served to carry Graves's squadron over the bar, and he was compelled to put to sea without the Robust and the Prudent, which were still at the dockyard. A junction was made with Hood's squadron outside the bar, where a line of battle was delivered to the several division commanders.

LINE OF BATTLE OF BRITISH FLEET

The Alfred to lead with the Starboard and the Shrewsbury with the Larboard tacks on board.

VAN�REAR ADMIRAL SAMUEL HOOD'S DIVISION

| Frigates |

Ships |

Guns |

Men |

Commanders |

Santa Monica

(To repeat signals) |

Alfred |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Bayne |

| Belliqueux |

64 |

500 |

Capt. Brine |

| Invincible |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Saxton |

| Richmond |

Barfleur |

90 |

768 |

Adm. Hood

Capt. Alex. Hood |

| Monarch |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Reynolds |

| Centaur |

74 |

650 |

Capt. Inglefield |

CENTER�COMMANDER IN CHIEF, REAR ADMIRAL THOMAS GRAVES'S DIVISION

Salamander

(fireship) |

America |

64 |

500 |

Capt. Thompson |

| Resolution |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Manners |

| Bedford |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Thos. Graves |

Nymphe

(To repeat signals) |

London |

98 |

800 |

Adm. Graves

Capt. David Graves |

| Royal Oak |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Ardesoif |

| Solebay |

Montagu |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Bowen |

| Adamant |

Europe |

64 |

500 |

Capt. Child |

REAR�REAR ADMIRAL FRANCIS DRAKE'S DIVISION

Sybil

(To repeat signals) |

Terrible |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Finch |

| Ajax |

74 |

550 |

Capt. Charrington |

| Princessa |

70 |

577 |

Adm. Drake

Capt. Knatchbull |

| Fortun�e |

Alcide |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Thompson |

| Intrepid |

64 |

500 |

Capt. Molloy |

| Shrewsbury |

74 |

600 |

Capt. Robinson |

N. B. If the Europe cannot keep up she is to fall into the Rear and the Adamant to take her station in the line.

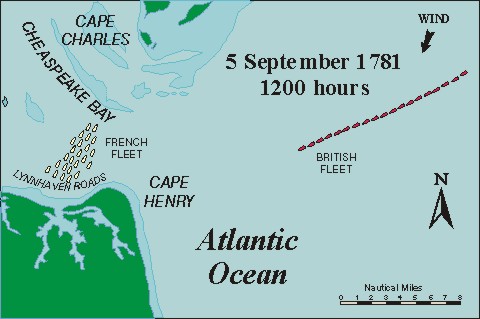

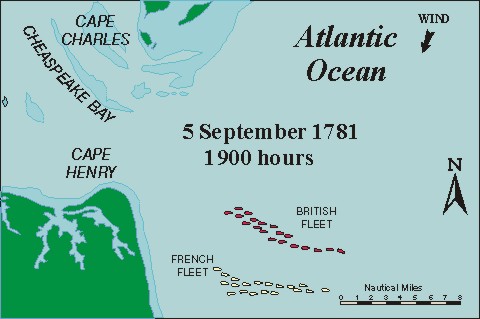

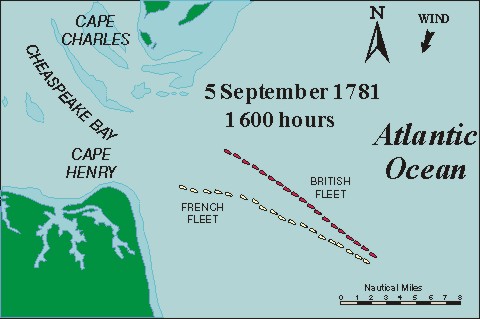

The British Fleet continued its course southward without receiving any information from the cruisers which had been stationed off the Delaware River and Chesapeake Bay, and on the morning of the 5th of September, under a favourable north-northeast wind, it approached the capes of the Chesapeake. At 9.30 a. m. the frigate Solebay, scouting in advance of the fleet, "made the signal. for a Fleet in the S. W." The course of the British ships at this time was southwest by west, and at 10 a. m. Cape Henry bore west by south 6 leagues from the flagship London. A half hour later all the cruisers with the fleet were called in and the signal made to prepare for action. At 11 a. m. the signal was made for a line of battle ahead at 2 cables' length asunder, the French Fleet being now clearly visible at anchor and

seemingly extending across the entrance to the bay, from Cape Henry to the Middle Ground. Having the wind, and the weather being fair, the British ships manoeuvred into position without difficulty and by noon all were getting into their stations. The log of the London at this time shows that Cape Henry bore west one-half south 4 or 5 leagues.

On the morning of the 5th of September the French Fleet was at anchor in Lynnhaven Roads awaiting tidings of the march of the allied armies under Washington and Rochambeau, and the return of the boats and crew sent up the James River. At 8 o'clock a frigate on the

lookout signaled 27 sail in the east, steering toward Chesapeake Bay. It was evident from the number of sail that the fleet signaled was not that of Comte de Barras, which was expected hourly. The Comte de Grasse immediately ordered all hands to prepare for action; he recalled the rowboats that were out for water; and signaled the ships to be ready to weigh anchor. The tide by noon permitting the fleet to sail, cables were slipped, and the ships were manoeuvred with such celerity that notwithstanding the absence of nearly 90 officers and 1,800 men

who had not yet returned from landing St. Simon's command, the fleet was under way in less than three quarters of an hour.

LINE OF BATTLE OF FRENCH FLEET

Lieutenant General le Comte de Grasse

AVANT-GARDE�DE BOUGAINVILLE, CHEF D'ESCADRE

| Ships> |

Guns |

Commanders |

| Le Pluton |

74 |

D'Albert de Rions |

| La Bourgogne |

74 |

De Charitte |

| Le Marseillais |

74 |

De Castellane de Masjastre |

| Le Diad�me |

74 |

De Monteclerc |

| Le Reflechi |

64 |

De Boades |

| L'Auguste |

80 |

De Bougainville

De Castellan |

| Le St. Esprit |

80 |

De Chabert |

| Le Caton |

64 |

De Framond |

CORPS DE BATAILLE�DE LATOUCHE-TR�VILLE, CHEF D'ESCADRE

| Le C�sar |

74 |

Coriolis d'Espinouse |

| Le Destin |

74 |

Dumaitz de Goimpy |

| La Ville de Paris |

98 |

De Grasse

De Latouche-Tr�ville

De SaintCezair |

| La Victoire |

74 |

D'Albert Saint-Hyppolyte |

| Le Sceptre |

74 |

De Vaudreuil |

| Le Northumberland |

74 |

De Briqueville |

| Le Palmier |

74 |

D'Arros d-Argelos |

| Le Solitaire |

64 |

De Cic� Champion |

ARRI�RE-GARDE�DE

MONTEIL, CHEF D'ESCADRE

| Le Citoyen |

74 |

D'Ethy |

| Le Scipion |

74 |

De Clavel |

| Le Magnanime |

74 |

Le B�gue |

| L'Hercule |

74 |

De Turpin |

| Le Languedoc |

80 |

De Monteil

Duplessis Parscau |

| Le Z�l� |

74 |

De Gras-Pr�ville |

| L'Hector |

74 |

Renaud d'Aleins |

| Le Souverain |

74 |

De Glandev�s |

|

|

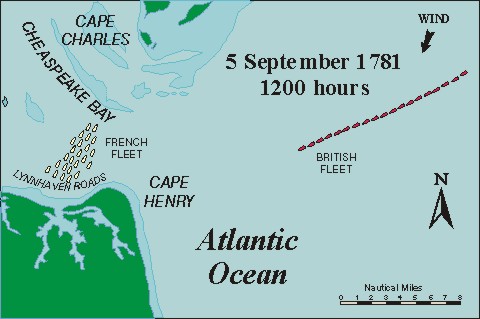

At 12.45 p. m. Admiral Graves, having observed that the French Fleet was getting under way, made the signal for the line ahead one cable's length asunder. Fifteen minutes later the signal for line ahead was hauled down and the signal made to form an east and west line at

a cable's length. At this time the weather was inclined to be squally, and Drake's division, being out of position, was directed to make more sail. The fleet continued on the course west by south for about an hour, the distance separating it from the French Fleet decreasing gradually, and His Majesty's ships were now on a line nearly parallel to the line of approach of the French Fleet. Admiral Hood, commanding the van division, impatiently awaited the signal to draw near the van of the antagonist and open the action. In the "Sentiments upon the Truly

Unfortunate Day" which Hood jotted down the day following the battle, he said that the enemy's van might have been attacked "with clear advantage, as they came out by no means in a regular and connected way," the French van being extended beyond the center and rear, and that the whole force of the British fleet could have been directed against it.

The log of the London at 2 p. m. says:

Found the Enemy's fleet to Consist of 24 Ships of the line and 2 frigates their Van bearing So. 3 Miles standing to the Eastward with their Larboard Tacks on board, in a line ahead.

The van of the British Fleet had now advanced as far as the shoal of the Middle Ground would admit, and a preparatory

signal to wear was made. At 2.11 Graves wore the fleet and brought it to, in order to let the center of the French line come abreast. The British ships were now on the same tack with the French and nearly parallel to their line, though by no means as far extended as was the French rear. The log of the Barfleur shows that at 2.15 P. M. Cape Henry was west by south 2 leagues.

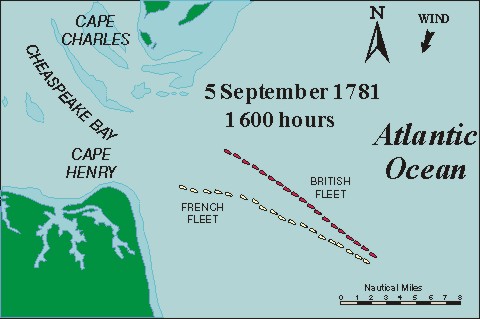

Both fleets were now headed to the eastward, and as the British Ships had the wind they were better able to manoeuvre. At 2.30 the leading British ship, the Shrewsbury, was signaled to lead more to starboard so as to approach the van of the French Fleet, the

signal being repeated at 3.17 p. m. to all of the van ships. At 3.30 the ships astern were signaled to make more sail, and at 3.34 the signal was again made for the ships in the van to keep more to starboard. This lack of contact between the two vans was due to the fact that at 3 p. m. the headmost vessels of the French Fleet were carried too far to windward for a well-formed line, due to the shifting of the wind and the movement of the current. De Grasse made the signal for them to bear away two points, so as to give all the vessels

the advantage of fighting together.

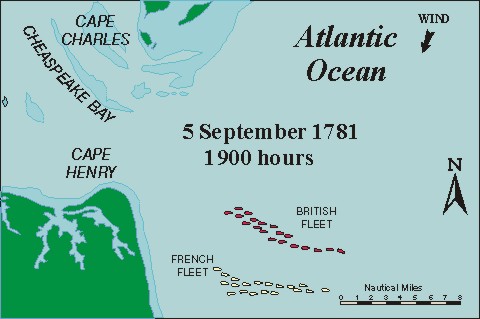

At 3.46 Graves made the signal for a line ahead at 1 cable's length, at which time the French ships were advancing very slowly. The day was coming to an end and the admiral, judging this to be the moment to attack, made the signal for the British ships to bear down and engage their opponents. The signal for line ahead was hauled down at 4.11 so that it would not interfere with the signal to engage close, and four minutes later the van and center of the British Fleet commenced the action. The French van, commanded by the Sieur de Bougainville, replied with a very brisk fire, followed in succession by all of the ships of the main body. The action soon became general in the British Fleet as far as the Resolution, now the second ship from the center toward the rear, and in the French Fleet as far as the rear ship of the center division.

|

|

There was considerable crowding in the English van and center when they bore down upon the French Fleet, which made it necessary at 4.22 to signal for the line ahead in order to extend the van. At 4.27 the signal for the line ahead was hauled down and the signal made for close action, this signal being repeated at 5.20. Ten minutes later Hood's rear division bore up. At different times during the action De Grasse edged away with the ships of the center division, thereby increasing the distance from the British ships which were opposite to them. This movement left the van ships of the French Fleet closely engaged, and they, in turn, were signaled to bear away. De Grasse says of the action at the time that at 5 p. m., due to the continued varying of the wind four points, the van of the French Fleet was again thrown too far to windward. Being desirous that the engagement become general, he again ordered his van to bear down, and the English van was ill treated. The French rear guard was making every effort to reach the rear and main body of the English Fleet, but the wind was against them.

The action was not progressing satisfactorily with the British, as several ships were much damaged, and at 5.35 the admiral made the signal for the frigates Solebay and Fortun�e to come within hailing distance to carry messages. Darkness was approaching when the frigates reported, and it being too late to give any additional battle orders, the Fortun�e was sent to the van and the Solebay to the rear with instructions to the ships to keep in a parallel line with the French and remain well abreast of them during the night.

Because of fading light the action could be continued no longer, and at 6.23 Graves made the signal for the line ahead at a cable's length and hauled down the signal for close action. Firing ceased on both sides at 6.30 p. m. A half hour later Cape Henry bore northwest 3

leagues distant from the London. The French Fleet at this time was about 2 miles to the leeward of the British. The loss of men sustained by the British in this action was 90 killed and 246 wounded. The French reported a loss of about 200 casualties.

At the time this sea battle was fought the long-continued practice in the British Navy of attacking ship with ship was strongly disfavoured by some officers of the fleet, who held that more decisive results were to be obtained by concentrating on several of the enemy's ships until they were put out of action. Admiral Hood's caustic comments on the battle, as noted in his "Sentiments," indicate how keenly disappointed he was in not getting into action with the rear division:

When the van of the two fleets got into action, and the ships of the British line were hard pressed, one (the Shrewsbury) totally disabled very early from keeping her station by having her fore and main topsail yards shot away, which left her second (the Intrepid) exposed to two ships of superior force, * * * that the signal was not thrown out for the van ships to make more sail to have enabled the center to push on to the support of the van, instead of engaging at such an improper distance (the London having her main topsail to the mast the whole time she was firing with the signal for the line at half a cable flying), that the second ship astern of the London received but trifling damage, and the third astern of her (the London) received no damage at all, which most clearly proves how much too great the distance was the center division engaged.

London, Flagship of Graves. [Illustration from original 1931 printing.]

Now, had the center gone to the support of the van, and the signal for the line been hauled down, or the commander in chief had set the example of close action, even with the signal for the line flying, the van of the enemy must have been cut to pieces, and the rear division of the British fleet would have been opposed to those ships the center division fired at, and at the proper distance for engaging, or the Rear Admiral who commanded it would have a great deal to answer for. Instead of that, our center division did the enemy but little damage, and our rear ships being barely within random shot, three only fired a few shot. So soon as the signal for the line was hauled down at twenty five minutes after five the rear division bore up, about half a mile to leeward of the center division, but the French ships bearing up also, it did not near them.

Admiral Rodney, upon learning of the battle, wrote to the Admiralty from Bath on the 19th of October, expressing his opinion of the strategy and tactics employed by Graves. His comments on the strategy of the English Fleet, preceding its appearance off the Chesapeake, are

based upon false premises and therefore are of no value. In regard to Graves's manner of fighting he said:

He tells me that his line did not extend so far as the enemy's rear. I should have been sorry if it had, and a general battle ensued; it would have given the advantage they could have wished, and brought their whole twenty four ships of the line against the English nineteen, whereas by watching his opportunity, if the enemy had extended their line to any considerable distance, by contracting his own he might have brought his nineteen against the enemy's fourteen or fifteen, and by a close action totally disabled them before they could have received succour from the remainder, and in all probability have gained thereby a complete victory.

When night came on Admiral Graves sent the frigates to the van and rear with orders to the division commanders to push for, ward the line and keep it extended with the enemy, his intention being to renew the engagement in the morning. The Fortune returned from the van

bearing the information that the Shrewsbury, Intrepid, and Montagu were unable to keep the line, and that the Princessa was in momentary apprehension of the topmast going over the side. Admiral Drake shifted his flag from the Princessa to the Alcide until the Princessa could make necessary repairs. Captain Robinson of the Shrewsbury had lost a leg, and Captain Colpoys of the Orpheus was placed in command of the ship. The following day the Terrible and the Ajax were found to be leaking badly.

|

|

During the morning of the 6th Captain Everett went aboard the Barfleur with a message to its commander from Admiral Graves, desiring Hood's opinion as to whether or not the action should be renewed. Hood's answer was:

I dare say Mr. Graves will do what is right; I can send no opinion, but whenever he, Mr. Graves, wishes to see me, I will wait upon him with great pleasure.

A conference between the three admirals was held that after noon aboard the London. Admiral Graves decided that it would be too hazardous to renew the action, in view of the large number of ships disabled, but he was not inclined to accept the suggestion made by Hood

of returning to the Chesapeake, where the French ships left at the York and James might be destroyed and some measure of succour rendered Cornwallis.

On the 7th of September Captain Duncan of the Medea, while on reconnaissance duty of the capes of Virginia, ran into the Chesapeake and was able to observe that the French Fleet had left their anchors. He directed the Iris to cut away the buoys, after

taking bearings upon them so that the anchors might be recovered later.

During the 7th and 8th the two fleets kept from 2 to 5 leagues apart, each endeavouring to take advantage of a shift in the wind to get the weather gage of the enemy, but neither commander being disposed to force an action. Meanwhile the wind, which was generally from

the northeast, was carrying both of the fleets far to the south, they being below Albemarle Sound on the 9th, and the British fleet of Cape Hatteras the day following. In the evening of the 9th De Grasse lost sight of the English Fleet; and fearing lest some change of wind might enable it to get into Chesapeake Bay, he resolved to return there himself to continue operations at that point and to take aboard the part of the crew left in James River. On the 11th the French Fleet came to anchor inside of Cape Henry, where a junction was made with the

squadron of De Barras, which had arrived in those waters the preceding day.

A council of war was held aboard the London on the 11th to determine what should be done with the Terrible. She had been so seriously damaged during the action of the 5th that water was gaining on her pumps, and there seemed little probability of being able to get her to New York or to any other port. The council recommended that the crew be removed and the vessel sunk. Fire was set to her on the night of the 11th, and in a few hours she disappeared beneath the waves.

The movement of De Grasse in the direction of the Chesapeake had been observed by Hood, and on the morning of the 10th of September he sent a note to Admiral Graves asking if he had any knowledge as to where the French Fleet was. Hood said in the note that the press

of sail which De Grasse carried the day before, and which he mug have carried during the preceding night to have been where he was at daylight on the 9th, seemed to indicate that the French Fleet was making for the Chesapeake. This letter occasioned another summons of Hood and Drake aboard the London, when much to Hood's astonishment he learned that Admiral Graves was as ignorant

as himself as to the location of the French Fleet. No frigates had been given the specific duty of observing the enemy's movements. The last entry in the log of the London, of the French Fleet being in sight, was dated 7 p. m. on the 9th. The question was put to Hood as to what should be done. He replied that he had previously explained his views, adding:

If it was wished I should say more, it could only be that we should get into the Chesapeake to the succour of Lord Cornwallis and his brave troops if possible, but that I was afraid the opportunity of doing it was passed by, as doubtless De Grasse had most effectually barred the entrance against us, which was what human prudence suggested we ought to have done against him.

Admiral Graves realized that he had permitted the situation to get out of hand and now turned his ships northward, with the hope that it was not yet too late to gain the Chesapeake ahead of the French. The fleet made little headway on the 11th, but the wind shifting to the southward that day, it reached a point southeast of Cape Henry by noon of the 12th. On the following morning the captain of the Medea signaled that the French Fleet was at anchor above the Horse Shoe in Chesapeake Bay. Graves transmitted this intelligence to Hood and again asked his opinion as to what should be done with the English Fleet. Hood's reply is characteristic:

Sir Samuel would be very glad to send an opinion, but he really knows not what to say in the truly lamentable state we have brought ourselves.

Another council of war was held on board the London on the afternoon of the 13th. The recommendations of the council, based upon the position of the French Fleet within the Chesapeake, the condition of the British Fleet, the season of the year so near the equinox, and

the impracticability of giving any effectual succour to General Cornwallis, were as follows:

It was resolved, that the British Squadron under the command of Thomas Graves Esqr., Rear Admiral of the Red,Sir. Samuel Hood Bart and Francis Samuel Drake Esqr., Rear Admirals of the Blue, should proceed with all dispatch to New York, and there use every possible means for putting the Squadron into the best state for service, provided that Captain Duncan who is gone again to reconnoitre should confirm his report of the position of the Enemy and that the Fleet should in the mean time facilitate the junction

of the Medea.

The additional report made by Captain Duncan confirmed his previous report that the entire French Fleet was anchored inside Cape Henry so as to block the passage, whereupon Admiral Graves determined to follow the resolution of the council of war, that the ships be

secured at New York before the equinox. The British Fleet sailed from the coast of Virginia on the 14th of September and arrived at Sandy Hook six days later.

* * * * * * *

When the English Fleet sailed from Sandy Hook on the 31st of August, Admiral Graves realized fully the seriousness of its mission. Nothing was to be feared from an encounter with the small squadron of De Barras, but there was much uncertainty as to the number of ships

that were coming from the West Indies and the place where they might be encountered. On the 5th of September, when Graves saw the enemy inside the capes of Virginia, he promptly decided to attack and lost not a moment in forming for action. Had he attempted to engage the French van shortly after it passed Cape Henry, and before wearing his own ships, he would have become involved in a very restricted area without the cape, and there would have been no opportunity to adopt the battle tactics of ship against ship which he

contemplated employing.

Having had six ships seriously damaged in the action of the 5th, it was impracticable for Graves to take the offensive the following or any succeeding day until repairs were made. As long as the wind remained in the northeast the best he could hope to do was to remain

to the windward of the French Fleet, and beat them back to the Chesapeake in case the French showed any intention of seeking that harbour.

The French Fleet, as soon as the enemy appeared, prepared to come out and fight, which was the only thing for it to do in view of its mission in America, its superior strength, and the necessity to provide a safe entry into the harbour for the squadron of De Barras. After the battle, however, De Grasse also was disinclined to force a second engagement. As long as he was to the southward of the English Fleet and the wind was from the northeast, he could not manoeuvre to bring on an engagement except by first tacking a great distance to the southeast. The initiative would have to be taken by his antagonist unless the wind shifted to the southward.

On the night of the 8th, realizing that both fleets had been carried about 60 nautical miles south of Cape Henry, De Grasse became fearful lea the British attempt to make the Chesapeake, and he decided it would be wiser for himself to attempt the move. That night he changed

his course to the eastward, and with full sail made for Cape Henry.[Ed. Note: Many authors have de Grasse executing the course change on 9 September to return to the Chesapeake.]

Either fleet, having possession of Chesapeake Bay and holding the ships at anchor on a curved line from a point inside Cape Henry to the shoals at the southeast end of the Middle Ground, a distance of 2 nautical miles, could have kept the enemy ships out of the bay, irrespective of the relative strength of the two fleets, The blockading fleet could not be attacked, unless the attacker was willing to engage in a very hazardous movement. He would be compelled to pass inside Cape Henry in a line ahead, approaching from the east or southeast, in which formation his van ships would become engaged successively, and it would be tempting fate too much to expect a favourable outcome for the enterprise. Once inside Cape Henry the attacking fleet would have no opportunity to manoeuvre, on account of the shoals, or to withdraw from the action. The battle would be to a finish, with all the advantages with

the blockading fleet.

Had the English Fleet succeeded in reaching an anchorage inside of Cape Henry, its position there might have resulted in saving Cornwallis's army, but the fleet itself would probably have been lost. No assistance of any moment could have been given to the British Army

as long as it occupied Yorktown, other than to share the food of the crew with the army; but the fleet could have covered a crossing of the York or James River by the troops, thus enabling Cornwallis to lead his army to safety. The war would thereby have been prolonged; but with the combined squadrons of De Barras and De Grasse on the outside, the English Fleet in time would have been taken, unless the French should have found it impracticable to maintain their station.

If the move begun by De Grasse on the night of the 8th to recover the anchorage at Lynnhaven Roads had been circumvented by the English, De Grasse would have been compelled to remain outside the harbour and there continue his part of the joint operations. His

return to the West Indies by the 15th of October would necessarily have been delayed, for he could not go back without the army of St. Simon now at Williamsburg, nor the 1,890 officers and men of his crew left in the James

River.

|

|

Return to top of this page.

Return to page on French Naval Leaders in the American War for Independence.

Return to page on the Yorktown Campaign.

Return to page on the First Naval Battle of the Virginia Capes (1781).

|

|

|

Following are links to webpages outside of the The Exp�dition Particuli�re Commemorative Cantonment Society's website. These are articles on the Battle of the Capes by respected naval historians:

"The Pivot Upon Which Everything Turned: French Naval Superiority That Ensured Victory At Yorktown"

By William James Morgan at

http://www.history.navy.mil/library/online/pivot.htm

"The Real Story of the American Revolution: The Battle Off the virginia Capes" by Michael J. Crawford at

http://www.rsar.org/military/navy/va-capes.htm

Of interest is this study by an American historian who specialized in British naval history. This work was published in The Canadian Nautical Research Society's The Northern Mariner/Le marin du nord, XIV No 4, (October, 2004),1-9.

"A Strategy of Detachments:The Dispatch of Rear-Admiral Thomas Graves to America in 1780."

http://www.cnrs-scrn.org/northern_mariner/vol14/tnm_14_4_1-9.pdf

|

|

|

Return to

Expédition Particulière

page.

|

|

This page was created 29 May 2003, and

last revised 31 December 2008.

|