West Indies Score Card

During the American War for Independence (1776-1783)

|

The theater of the West Indies is often referenced, but incompletely covered in most histories about the American War for Independence. It was a theater that meant more in economic value to the European powers than did the 13 colonies in rebellion.

The West Indies had an important influence on the sophisticated strategies of the European nations who were conducting a world wide war, in contrast to the war aims of the American colonies fighting for independence from Great Britain. This difference probably explains why the West Indian theater is slighted in most works about the �American Revolution'. The array of naval battles and island captures in the West Indies present a difficult picture to understand the actual wartime results in that theater. This page is an attempt to depict the scope of the events and to show an overall portrayal of exchanges in island possessions.

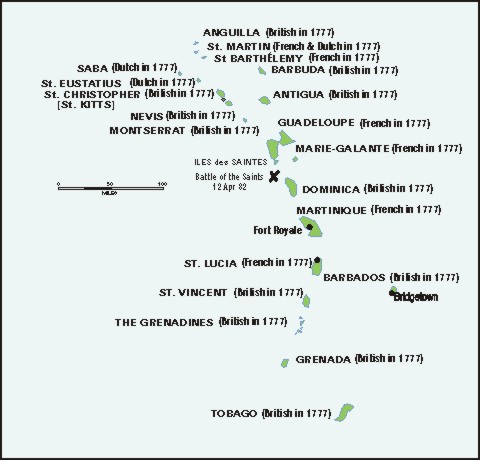

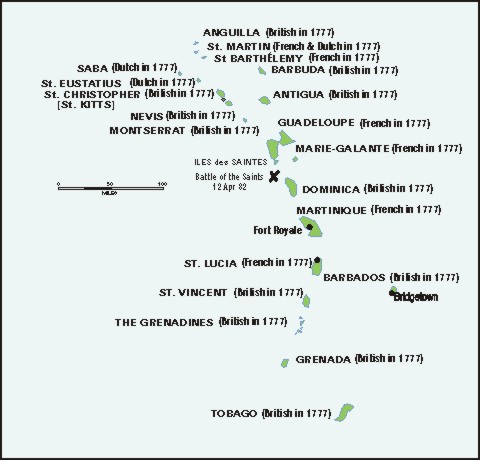

Below are maps reflecting a general scope of the theater. The first map is of the full West Indies; the second is of the Lesser Antilles where most of the fighting and island exchanges took place. Green areas represent Spanish possessions, Red for British possessions, Blue for French possessions, and Yellow for Dutch possessions. It should be noted that the colored areas reflect �territories claimed', while actual �occupation and control' was limited to a few small settlements along coasts and rivers.

|

|

|

|

WEST INDIES

|

|

In the greater West Indies, the most dramatic exchange was the loss of British East Florida, due to the campaign of the Spanish Governor Bernardeo de Gálvez.

The Bahamas were affected by the seizures of New Providence (now Nassau) island. The island was never strongly defended, and was easily taken and briefly held by Americans early in the war. It was captured by Spain in May 1782, but captured early the following year by Loyalists from Florida -- though the ongoing peace negotiations in Europe had already agreed to return it to Great Britain.

|

LESSER ANTILLES

Islands' possession shown as of 1777, prior to France's official entry into the war in 1778.

|

Ref.

No. |

as of

1777 |

Remarks [See note 1.] |

1783 before

Peace Treaty |

After

Treaty |

| 1. |

|

DOMINICA, captured by French 7 Sep 1778. |

|

|

| 2. |

|

ST. LUCIA, captured by British 28 Dec 1778 |

|

|

| 3. |

|

ST. VINCENT, captured by French 19 Jun 1779 |

|

|

| 4. |

|

GRENADA, captured by French 4 Jul 1779 |

|

|

| 5. |

|

ST. EUSTATIUS [EUSTATIA], captured by British 3 Feb 1781, re captured by French 26 Nov 1781. |

|

|

| 6. |

|

SABA experienced same changes as nearby, larger St. Eustatius. |

|

|

| 7. |

|

ST. MARTIN [See Note 2.], occupied by British in January 1779, re captured by French 24 Feb 1779. Later experienced same changes as nearby, larger St. Eustatius. |

|

|

| 8. |

|

TOBAGO, captured by French 2 Jun 1781. |

|

|

| 9. |

|

St. CHRISTOPHE (KITTS), captured by French 12-14 Feb 1782. |

|

|

| 10. |

|

NEVIS, captured by French 20 Feb 1782. [See note 3.] |

|

|

| 11. |

|

MONTSERRAT, captured by French 22 Feb 1782. |

|

|

| 12. |

|

ST. BARTHÉLÉMY [BARTHOLOMEW], occupied by British in January 1779, re captured by French 28 Feb 1779. Later experienced same changes as nearby, larger St. Eustatius. |

|

|

|

|

NOTES to go with foregoing table:

1. Secondary sources given in the most available published histories often do not agree as to the exact date of particular events in the West Indies. No doubt, archival records are not perfect. However, there is general agreement within several days time frame. The dates given above have been reviewed by a current French naval historian, Patrick Villiers who has access to and has conducted current research in the French archives. His published work is cited at the end of this webpage.

2. St. Martin was held jointly by the Dutch and French since 1648.

3. The French recovered the Dutch settlements of Demerara and Essequibo (on the Guiana coast of South America, and which had been seized by British privateers in 1781) on 22 January 1782.

|

|

To a large extent the capture of the islands was an attempt to gain leverage in later peace negotiations. The final Peace Treaty dispositions were worked out against a broader geographical perspective -- actually a world - wide view was considered as the negotiations dragged on until September 1783, when the last Definitive Peace Treaties were signed between Great Britain and the Allies [except Holland, which settled a little later].

France returned many of its Lesser Antilles' conquests to regain the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon and certain fishing rights in Newfoundland [North America]. These indefensible, but most valuable possessions were seized by the British early in the conflict. These islands remain part of France in the Twenty First Century.

In the West Indies, the Treaty of 1783 allowed France to recover St. Lucia and to gain Tobago. Great Britain was allowed to recover Dominica, Grenada, the Grenadines, St. Vincent, St. Christopher [Kitts], Nevis, and Montserrat. Spain gained East and West Florida, but relinquished her claim to the Bahamas and conceded to Great Britain the right to cut logwood in the Bay of Honduras.

Spain entered the war with the major aims of regaining Gibraltar, Minorca, and Jamaica. Spain did regain Minorca, which she captured with the assistance of French forces. However, the British garrison at Gibraltar held out against all attacks by the Spanish and French. To some extent, the British struggle to defend 'the Rock' restricted Britain deploying sufficient naval forces needed in the 1781 Yorktown Campaign. Spain's attempted conquest of Jamaica was crushed with the defeat of the French naval squadron at the Battle of the Saintes (12 April 1782). Contrary to suggestions in many popular writings, the British naval victory at the Saintes did not produce any island gains for Britain in the West Indies. [The bottom of this page has a link to a webpage on the 'Strategic Assessment of the Battle of the Saintes'] The continuing threat to Gibraltar and the French sudden offensive in the Indian Ocean drew British naval assets away from the Western Hemisphere, leaving a dominant presence of Spanish and French naval forces in the West Indies. However, the allies were not strong enough to re launch another immediate attempt upon Jamaica.

Conquests and losses in the West and East Indies appear 'practically balanced' only after the peace negotiations. Entering the negotiations, France had the best of the �bargaining chips' in the West Indies.

Return to top of page.

Bibliography

Patrick Villiers. Marine de Louis XVI (Grenoble,1983).

Patrick Villiers. Le commerce colonial atlantique et la guerre d'Ind�pendance des

Etats-Unis,1778-1783 (New York, 1977).

Jonathan R. Dull. The French Navy and American Independence, A Study of Arms and Diplomacy, 1774-1787

(Princeton University Press, NJ, 1975)

Captain W.M. James. The British Navy in Adversity: A Study of the War of American Independence (London,1926, rp.1973).

Ernest H. Jenkins. A History of the French Navy (US Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD,1973).

René Chartrand. The French Army in the American War of Independence (London, Osprey 'Men-at-Arms Series' (244), 1991).

Captain Alfred T. Mahan. The Major Operations of the Navies in the War of American Independence (London, 1913).

Michel VERG�-FRANCESCHI, La Chronique maritime de la France d'Ancien R�gime 1492-1792 (Paris 1999),

Piers Mackesy. The War for America 1775-1783 (University of Nabraska Press, Lincoln, 1993).

Chevallier. Histoire de la Marine fran�aise pendant la guerre

d'Ind�pendance (Paris, 1877).

Return to top of page.

Return to French Naval Leaders in the American War for Independence.

Return to the Second Battle of the Virginia Capes (1781).

Webpage on 'Strategic Assessment of the Battle of the Saintes (12 April 1782)'.

Page posted 9 January 2004, revised 11 March 2007.

|