| [ Previous ] [ Next ] |

|

[more information] |

One of the great comedy-relief characters of the Revolution -- possibly the whole 18th century -- is Georgey Hanger, cavalryman, rake, coal merchant, peer of the realm, gambler and generally strange person. I can find no record of where George and Banastre Tarleton first met. It may have been in Savannah, before the army marched north to Charleston. Or perhaps they already knew each other, having partied together in Philadelphia over the winter of 1777-78, or worked together around New York, where John Graves Simcoe records combined operations involving the Queen's Rangers, the Legion and the Hessian regiment to which George then belonged. Wherever their acquaintance began, they renewed it after the surrender of Charleston. Contemporary gossip suggests that Ban found in George such a companion spirit that he decided he was the perfect man to command the Legion's cavalry wing. From that leap of total illogic came a lifelong friendship.

George Hanger was born in Gloucestershire, on October 13, 1751, the third son of Lord Coleraine. Theirs was scarcely an ancient lineage. George's father, Gabriel -- a country squire who dabbled in politics -- had managed to get himself named the fourth Baron Coleraine in 1762, despite the fact that his only claim to the title was that a female relative, Anne Hanger, had been married to the third Baron Coleraine, who had died without heirs. Gabriel doesn't seem to have ever taken his seat in the house of Lords, and his example was followed by his three sons, who inherited the title in succession. It finally became extinct upon George's death.1

George was the youngest of seven children born to Gabriel and his wife, Elizabeth Bond. Three of their children died in childhood, leaving George to grow up with a sister, Anne, and two brothers, John and William, both of whom were destined to become notorious for their high-living ways. He was educated at Eton, where he excelled in Latin and detested Greek. Despite having, by his own admission, dedicated his energies to hunting by day and womanizing by night, he managed to graduate. Of his early life, he offers this amusing summary:

I was early introduced into life, and often kept both good and bad company; associated with men both good and bad, and with lewd women, and women not lewd, wicked and not wicked; -- in short, with men and women of every description, and of every rank, from the highest to the lowest, from St. James's to St. Giles's; in palaces and night cellars; from the drawing-room to the dust cart....Human nature is in general frail, and mine I confess has been wonderfully so.2

|

After his graduation from Eton, George's dad sent him on to the University of Göttingen. George stayed there long enough to perfect his German, then ran off and joined the army -- of Frederick the Great.

Returning to England in 1771, George foisted himself off on the 1st Regiment of Footguards as a ensign. He broke up the monotony of peace time army life by marrying a gypsy girl, with whom he was deliriously happy -- right up until she ran off with a tinker. After that, George gave himself over to Fashion, spent a phenomenal amount of money on his wardrobe, and became a macaroni. Thanks to a hot temper, he had fought three duels of honor before he was even twenty-one -- and presumably he attended all of them extremely well dressed.

In 1776, his commanders must have noticed that he wasn't actually doing anything in his official capacity as a soldier, for they promoted a junior officer over him. George was so offended by this unfair treatment that he resigned, then promptly turned around and bought himself a captain's commission in a jäger detachment. (They had better uniforms, anyway.) He was soon on his way to America under Knyphausen.

Serving with the Hessians, he must have seen action of various sorts in the north, but information on his personal contribution to the war is scanty and often confusing. In his memoirs, he reveals that he was the officer who delivered the Earl of Carlisle's peace initiative to the rebels. At some point prior to 1779, he became friends with the Marquis de Lafayette. When Lafayette's aide-de-camp, Presley Nevill, was about to embark for France, the Marquis advised that, "Had you the bad luck of being made a prisioner you might apply to [...] Mr. George Hanger[.] Hanger, Lafayette assured him, would do what he could to ensure Nevill's "speedy relief and add this obligation to all the marks of affection, I have already received[.]"3

It is also certain that Hanger fought at Monmouth Courthouse, for late in his life he would pen an unexpectedly vivid vignette about its prelude:

I shall never forget the night before the battle of Monmouth Court-House. It was uncommonly dark, with frequent thunderstorms and rain. It fell to my lot, that night, to have the outermost picket. Never could man pass a more anxious time; the fires all put out, the enemy's patroles feeling us and firing every half hour and oftener at the advanced sentries; our men on sentry firing sometimes at the enemy's patroles and sometimes at cattle in the woods, as soldiers will do when they hear a noise in the bushes, challange, and gain no reply; the night so dark (taking it by turns every half hour, with two lieutenants, to visit the sentries) as not to be able to perceive our own men until we came close upon them and in danger of being fired at by our own men. Such a night of anxiety and danger I never since passed, and blessed my God when the day began to dawn.4

In July, 1778, at Sir Henry Clinton's behest, he raised an elite chasseur company from among the Hesse Cassel regiments in New York. It was disbanded in November 1778, but George raised a new company of 120-200 chausseurs in December, 1779, in time to accompany the opening of the Southern Campaign. Some time before October, 1779, his fluency in German had also earned him a post as one of Clinton's aides-de-camp, a post he filled until Clinton returned to New York after capturing Charleston.5

Unfortunately, the bad weather which plagued Clinton's expedition on its southward journey cost George his command. In his January 4th journal entry, Captain Johann Hinrichs of the Jäger Corps reported:

"Of the entire fleet only forty-eight ships were together; but among the missing were the Russell, the Renown, and the Robust, which presumably were with the greater part of the missing ships. The absence of the Renown allowed us to hope that the Anna transport, which was carrying Captain von Hanger's company of chausseurs and had lost her mainmast and mizzenmast in the first storm, was still afloat and the chausseurs alive, for she had been taken in tow by the Renown after the first storm."6

The crippled Anna never made it to the Carolinas. The tow cable snapped and, unable to maneuver, she drifted clear across the Atlantic to Britain. Provisioned for only four weeks, she was at sea for twice that before finally being wrecked on the shore of Cornwall on February 25. The survivors of Hanger's command were sent on to Plymouth, and sailed for the New World again in August, finally arriving at New York in October, 1780, where the unit was disbanded.7

Fortunately for Hanger, he had not been travelling with his men, but aboard "the ship John, at the particular request of... Sir Henry Clinton, to see that proper attention was paid to three favourite horses of his during the voyage[.]" Minus his chausseurs, he reached the south and took part in the siege of Charleston as a member of Clinton's staff. Proving he could be a soldier when the mood struck him, George was highly effective in scouting the defenses of the city. When Sir Henry made plans to storm the town if it failed to surrender, said Simcoe, "the point from whence this attack was to have been made, had been privately reconnoitred by that gallant officer Capt. Hanger."8

Before returning to New York after the surrender of Charleston, Clinton named Hanger Deputy Inspector of Militia, with a brevet rank of major. The job would have required him to assist Major Patrick Ferguson in recruiting and training local loyalists. Lyman Draper claims that Ferguson had originally requested Hanger and his command be assigned to his corps:

"When Sir Henry Clinton fitted out his expedition against Charleston, at the close of 1779, he very naturally selected Major Ferguson to share in the important enterprise. A corps of three hundred men, called the American Volunteers, was assigned for his command -- he having the choice of both officers and soldiers... At his request, Major Hanger's corps of two hundred Hessians were to be joined to Ferguson's.9

Hanger and Ferguson were friends so it is quite possible the assignment was by mutual consent, but his chausseurs were casualties of the weather, and once he had the job of organizing the local Loyalists, George seems to have found it not at all to his taste. In the end he held his position as Ferguson's second-in-command for only a matter of weeks before moving on.

After the surrender of Charleston George had settled into quarters in the city in his customary spartan, military fashion. He quickly became notorious for what Bass calls the "train of strumpets, dogs and monkeys" he kept in his rooms. Writing a century earlier, Garden was more blunt, condemning George for "introducing into the best apartments of the most respectable families, his cats, his dogs, and his monkeys, while revelling himself in every species of sensuality, under the eyes of the unprotected females on whom he was billetted."10

[more information] |

Banastre Tarleton was so impressed by Hanger's military prowess or his lifestyle or both that he wrote privately to John André in New York, asking to have Hanger appointed major for the Legion cavalry. In August 1780, without waiting for a response from Clinton, he wheedled Lord Cornwallis into signing off on the assignment.11

Hanger served on Tarleton's staff for the remainder of the war, but his active fighting days with the British Legion amounted to roughly six weeks. He was with them at the battle of Camden, and while there are no reliable reports on his participation, Garden provides a spurious tale about him. The concept of this snippet fits so well with the progress of Hanger's life that one can almost believe it. Supposedly, when asked about the battle, George replied:

"Flushed with victory, and eager in pursuit, my arm was too well employed to allow much time for observation; but, overtaking the wagon of De Kalb, on which was seated a Monkey, fantastically dressed, I ceased to destroy, and addressing the affrighted animal, exclaimed, 'You, Monsieur, I perceive, are a Frenchman and a gentleman. Je vous donne la parole.[']"12

Hanger also took part in the William Washington masquerade, and assumed temporary command of the whole Legion when Tarleton fell ill in September, 1780. This period of command was marked by a considerable lack of success.

The end of George's active period with the Legion is a matter of some confusion. According to Tarleton's Campaigns, he was wounded while leading a cavalry charge at Charlotte. In his own memoirs, George merely states that he collapsed with yellow fever when Ban was just starting to recuperate, and set out to cure himself with an exclusive diet of port wine laced with opium. It must have been effective, for he survived and eventually recovered. Possibly he contracted the disease during his hospital stay after he was wounded leading an ill-chosen cavalry charge at Charlotte.

He spent part of that time recuperating in Bermuda, and his disability leave kept him out of action until after Yorktown, though he seems to have been in New York at the time of Cornwallis's surrender, and prepared to be part of Clinton's abortive rescue mission. He was definitely in New York by November, 1781, when he drew a passing mention in Peebles' journal.13

At the end of the war, George stayed on in America after Tarleton returned home. He remained in command of the Legion on Long Island at least until November, 1783, and was tasked by Sir Guy Carleton with settling many of the veterans in Nova Scotia. Unfortunately, he also seems to have been responsible for the disastrous choice of settlement site. In September 1783, Governor Parr wrote Carleton that "Major Hanger seem'd very happy to have Port Mouton allotted for the Legion."14

The exact date of his return to Europe is unknown, but the dense paper trail of documents which mention him or bear his signature make it unlikely that he left New York earlier than the beginning of 1784. It can be documented that he spent part of that year in Hanover, running an errand from the Prince of Wales to his brother, Prince Frederick, who was living there at the time. George was already in severe financial difficulties before he even set foot on the shore of his homeland. He recounts the events which led to his financial ruin in great detail in his memoirs, but as with the rest of that highly entertaining document -- which goes a long way, I think, towards proving that George was comedy writer Dave Barry in an earlier life -- it is difficult to decide how much of it to believe.15

Living from pillar to post, he rejoined Banastre as part of the Prince of Wales' high living jet set -- a lifestyle neither of them could afford -- and supported himself by horse racing (as a rider) and sponging off friends. One of his most famous -- or infamous -- exploits was organizing a cross-country challenge race between a flock of turkeys and a flock of geese, an event attended by both the Prince of Wales and the Duke of York. Other exploits and examples of his humor show up haphazardly in the memoirs of the time, such as Robert Huish's account of his first appearance at court and how it resulted in George "killing" Richard Brinsley Sheridan in a duel, George's stint as an apple seller, and this snippet from Joseph Farington's diary entry for August 21, 1803:

George, some years ago was frequently of the Prince of Wales's parties. At one of the entertainments given by the Prince, His Royal Highness filled a glass with wine and wantonly threw it in Hanger[']s face. George with[ou]t being disconcerted immediately filled his glass and throwing the wine in the face of the person who sat next to him bid him pass it round: -- an admirable instance of presence of mind & Judgment upon an occasion of coarse rudeness.16

While this snippet is almost certainly apocryphal, the newspapers provided a running account of George's (mis)adventures which were equally strange. For instance:

Hanger's encounter with the fishwife, as shown in a contemporary cartoon. |

Major H-gn-r, on his late tour to Plymouth with the Prince of Wales, met with an accident which might have produced very disagreeable consequences. In walking before his Royal Highness to keep off the crowd, a fish-woman, whom he had pushed aside rather disrespectfully, by giving the Major a fisty-cuff, which, unluckily for his situation, knocked him into a kennel, to the no small entertainment of the Prince and his party, who laughed most heartily at the dismal distress of the Major.17

In July, 1787, he extended his eccentricities by having a long and rather peculiar poem published in the papers in London and Brighton, entitled "Ode to Bacchus."

Through the remainder of the 1780s, Hanger gained a reputation for his rough-and-ready involvement in Whig politics, and his interest in the sport of boxing as a spectator and, occasionally, a participant. He also drew notice for his colorful language, which led The Times to comment, "George Hanger, who swears in common conversation more in an hour than a Chancery-Lane buffer in Court does in a term..."18

When Banastre was publicly attacked over his command decisions at Cowpens, George proved again that he could apply himself when given enough incentive. He sprang to his friend's defense with a flurry of pamphlets and newspaper articles, including An Address to the Army; in reply to Strictures, by Roderick M'Kenzie, (Late Lieutenant in the 71st Regiment) on Tarleton's History of The Campaigns of 1780 and 1781. These may or may not have had an effect on public opinion, but they certainly amused the newspaper critics.

Eventually, George's financial situation got so bad that he was forced to consider taking an honest job. Beginning in 1790, he went to work as a recruiter for the East India Company, but didn't manage to save himself from financial ruin for long. A reorganization within the Company, including a restructuring of their recruiting methods, cost him his job, and at nearly the same time, a tightening of the purse strings within the Prince's household cost him his position as an equerry. Bereft without warning of what had been a comfortable income, Hanger wound up spending several months in debtor's prison (June 1798 - April 1799). He used the time to pen his memoirs. When he was released, he scraped together a small amount of money and established himself as a coal merchant. Against all expectations -- and blithely ignoring the reactions of his wealthy and well-bred acquaintances -- he flourished "in trade."19

[more information] |

When England became embroiled in the wars against Napoleon, George returned briefly to service as Captain-commissary to the Royal Artillery Drivers, but retired (on full pay) in 1808. His elder brother died in 1814, leaving George the title of Lord Coleraine and a considerable fortune -- which enabled him to live out the remainder of his life in comfortable dissipation.

In his last years George thumbed his nose at convention one final time by marrying his cook or housekeeper. (There seems to be no surviving record of the marriage, but George referred to her as his wife when he made his will.) There is very little information to be found about Mary Anne Katherine Hanger. Her maiden name was possibly either Greenwood or Parsons, and The Complete Peerage gives her date of birth as c.1776, so she was considerably younger than George.20

They had one son, John Greenwood Hanger, who was baptized on September 5, 1817. This event seems to have occurred when John was a teenager or adult, for Melville quotes a letter written by Hanger to his friend, Major James, which includes this whimsical comment:

I forgot to tell you something that will make you laugh. When my boy, John, was appointed to a place in the Custom House, they sent for the register of his birth and christening. It came out that he had never been christened at all. However, I got over it by procuring two persons to make oath of the day of his birth, and age. You will fully agree with me that this ceremony having been omitted, would be no impediment to his entering the kingdom of heaven, though it appears to be some impediment to his entering the kingdom of the Custom House.21

Assuming Melville is correct in assigning this letter a date of 1814, John was of working age at the time of his baptism, which may have taken place as a result of difficulties such as that mentioned.

[more information] |

George died in London on March 31, 1824, of a "convulsive fit." His son was still living at the time, but did not inherit the title Lord Coleraine -- in fact, George seems to have never formally claimed it himself. An obituary appeared in The Gentleman's Magazine, (May 1824) which paints an interesting picture of how George's sense of humor was viewed by his contemporaries.

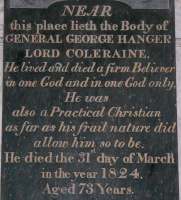

George is buried in St. Mary's Church, in the village of Driffield, Gloucestershire, with most of his close family. According to The Complete Peerage, his monumental inscription makes note that he was "a practical Christian, as far as his frail nature did allow him so to be."22

His widow died, aged 70, on December 27, 1846 at Ridgemount Place, Hampstead Road, (London), Middlesex. She left the bulk of her estate to John and his wife Mary.23

George deserves a biography, but to the best of my knowledge no one has taken up the challenge. His memoirs, The Life, Adventures and Opinions of Colonel George Hanger, written by Himself were published in 1801, and form an utterly strange and delightful glimpse into Georgian society.

He is also the author of various pamphlets and short essays, on subjects ranging from sports shooting (George laid claim to being the best shot in the British army) to the defense of London in the event of an invasion by Napoleon.

I was recently reminded that Georgey makes a brief, but funny and extremely in-character appearance in Regency Buck by Georgette Heyer (1935, but reprinted many times since then).

[Thanks to Doc M for rooting out the information on George's genealogy, including his marriage and the existence of his son.]

| [ Index ] | [ Previous ] [ Next ] |

1 Except where otherwise footnoted, information on Hanger's life is taken (with a certain amount of trepidation) from his own memoirs, George Hanger, The Life, Adventures and Opinions of Colonel George Hanger, written by Himself, 2 vols. (London: J. Debrett; 1801), supplemented with factoids from Robert D. Bass; The Green Dragoon; The Lives of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (New York: Henry Holt and Company; 1957) and Lewis Melville, The Beaux of the Regency, 2 vols. (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1908). A soft copy of the memoirs are available on this site. Bass seems to have derived his information largely from the memoirs and Melville, supplemented by various newspaper accounts, etc.

His birthdate is in G. E. Cokayne, The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, 6 vols. (London: The St. Catherine Press; 1913), 3: 369. According to George, Anne Hanger was his father's sister, but Doc M's research into his genealogy indicates she could have been no closer than a first cousin. This is borne out by a letter from Gabriel Hanger, in which he makes his application for the title saying "that title being extinct by the death of the last Lord Colerane, whose Lady was my first cozen." Printed in Melville, 1:22. George's tongue in cheek summary of the event runs as follows: "[M]y father was not in the most distant degree related to him, except by marriage. Hare, Lord Coleraine, however, dying without issue, or heir to the title; my father, Gabriel Hanger, claimed it, and with just as much right as the clerk or sexton of the parish. After the same manner as Jupiter overcame the beautiful Danae, did he prove an undoubted right to the title, and was created a peer of Ireland." Hanger, Life, Adventures, 2: 37. [ back ]

2 Hanger, Life, Adventures, 1: 10-11. [ back ]

3 Hanger, Life, Adventures, Vol. 2, Chapter 5. Phillip R.N. Katcher, Encyclopedia of British, Provincial and German Army Units, 1775 - 1783 (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1973). Marquis de LaFayette to Presley Nevill, 07 Jan 1779, in M.J.P.Y.R. Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de LaFayette, Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, ed. Stanley J. Idzerda, 5 vols. (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1977-1981), 2:219-220. [ back ]

4 George Hanger, Colonel George Hanger, to All Sportsmen (London: Printed for the author, 1814), pp217-8. [ back ]

5 John Charles Philip von Krafft, "The Journal of Lt. John Charles Philip Von Krafft," Ed. T.H. Edsall, Collections of the New York Historical Society for the Year 1882 (New York: New York Times, (1883) 1968), 55-6. In a letter, dated October 28, 1779, to Lord George Germain, Clinton mentions a dispatch "sent ... by my aide-de-camp Captain Hanger." (CO 5/98, in K.G. Davies, ed., Documents of the American Revolution, 1770-1783, 21 vols. (Dublin: Irish University Press, c1977-1982), 17: 237. Hanger also mentions serving in the post in New York, George Hanger, to All Sportsmen, p87. Bernhard Alexander Uhlendorf, ed. and trans., The Siege of Charleston, with an Account of the Province of South Carolina; Diaries and Letters of Hessian Officers from the von Jungkenn Papers in the William L. Clements Library (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1938), p13n1 and p367. [ back ]

7 The Anna's terrible voyage is described in Max von Eelking, Die Deutschen Hülfstruppen im Nordamerikanischen Befreiungstriege 1776 bis 1783 ((1863) Kassel : H. Hamecher, 1976), 2:63-4. The English translation/abridgement of the book, entitled The German Allied Troops In The North American War Of Independence, 1776-1783 (J. Munsill's Sons, 1893) mentions the ship being blown across the Atlantic, but deletes all nasty details such as suggestions of cannibalism. [ back ]

8 Uhlendorf, p24n1. John Graves Simcoe, A History of the Operations of a Partisan Corps called the Queen's Rangers (North Stratford, New Hampshire: Ayer Company, 2000), p139. Hanger, Life, Adventures, 2: 391-392. Passing mentions of Hanger fulfilling his role as aid-de-camp throughout the campaign also occur in Sir Henry Clinton, "Journal of the Siege of Charleston, 1780," ed. William T. Bulger, The South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine, 66:147-174 and Peter Russell, "The Siege of Charleston: Journal of Captain Peter Russel, December 25, 1779, to May 2, 1780," ed. James Bain, Jr., American Historical Review, 4:478-501. Russell also confirms that Hanger sailed south aboard the John. [ back ]

9 Lyman Draper, King's Mountain and its Heroes (Johnson City, TN: The Overmountain Press, 1996), p61. [ back ]

10 The "strumpets, dogs, and monkeys" comment is Bass, p86. Garden's sniffy putdown is in Alexander Garden, Anecdotes of the Revolutionary War in America, with Sketches of Character of Persons the Most Distinguished, in the Southern States, for Civil and Military Services (1822, Spartanburg, S.C.: The Reprint Company, 1972), p267. [ back ]

11 That's the order of events given in Bass, Green Dragoon, pp86-89, at any rate. In his memoirs, George tells a slightly different version, Hanger, Life, Adventures, 2: 402-407 [ back ]

13 John Peebles, The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782, ed. Ira D. Gruber (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998), p497. [ back ]

14 George's continued presence in the new world through 1782-83 can be charted by a series of minor documents referring to him or containing his signature. For instance, a Legion muster roll, dated Long Island, 3d February, 1783, bears the signature "George Hanger, Major Cavl Brith Legn." (Public Archives of Canada, Series C, Record Group 8, Volumes 1883 to 1885, Reel C 4221.) A letter from Alexander McDougal (private, 71st Reg.) to Sir Guy Carleton, 24 May 1783, in Historical Manuscripts Commission, Report on American Manuscripts in the Royal Institute of Great Britain, 4 vols. (London: Printed for His Majesty's Stationery Office, 1901-9), 4:100, is marked with the addendum, "Speak to Major Hanger about this officer" which indicates George was still present in New York. An "Abstract of 61 days' pay for the British Legion Cavalry," 25 Apr - 24 Jun 1783, in Ibid., 4:177 is also signed by Hanger. Another letter, Maurice Morgan to Banastre Tarleton, 09 Jul 1783, Ibid. 4:214, also mentions Hanger in a way that signifies his presence, as does his signature on a pay abstract for the period 25 Jun - 24 Aug 1783, Ibid., 4: 300. The latest documents I could find are a pay abstract dated 24 Oct 1783, Ibid., 4: 426, and a letter to Sir Guy Carleton, undated but filed in November of that year, Ibid., 4: 471. The choice of Port Mouton is mention in Gov. John Parr to Sir Guy Carleton, 20 Sep 1783, Ibid., 4:367. [ back ]

15 The Prince of Wales mentions that Hanger was "coming to visit" Hanover in a letter to his brother, Frederick, dated 16 May 1784. A month later, Frederick mentioned seeing him there "last week." Both letters in George IV, The Correspondence of George, Prince of Wales, 1770-1812, ed. A. Aspinall, 8 vols. (London: Cassell, c1963-71), 1:145-6. [ back ]

16 Joseph Farington, The Diary of Joseph Farington, ed. Kenneth Garlick and Angus Macintyre, 16 vols. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press; c1979), 6: 2112. Unfortunately, while this story certainly fits George's personality perfectly, it is probably the result of multiple retellings over a number of years which have changed the original information completely. The March 11, 1783 issue of The Morning Herald ran this tidbit: A few nights since, a celebrated Duke, after supping with the Prince of W----, and drinking rather freely, gave for a toast "A speedy coro---tion!" This intended compliment, however, failed in its effect; for his Royal Highness, with a proper spirit of indignation, filled a bumper, and threw it into the Duke's face. The offender struck with the impropriety of his own conduct, thought the best way was to put it off with a laugh, and filled his own glass, and dashed the contents thereof into the face of Col. -----, who sat next to him, saying, "His Royal Highness had given a new-fashioned sentiment in preference to my toast, so pray put it round!" It sounds suspiciously like the anecdote Farington heard from Sir Thomas Lawrence in 1803, and isn't an incident which is likely to have happened twice with minor variations. George couldn't even be "Col. ----" since the incident took place while he was still in America. [ back ]

17 The Times (24 Jan. 1788). [ back ]

18 The Times (8 Aug. 1788) for the quote. Any run of London newspapers through the 1785-89 period will produce snippets on his "career" as a Whig enforcer, and his active interest in pugilism. [ back ]

19 The Times (16 Oct. 1790), reported "Colonel Hanger now figures in the world as Recruiting Serjeant to the Hon. East India Company..." Melville, 1:31. Hanger, 2:460-469. [ back ]

20 Cokayne, 2: 365-370, entry for "Coleraine", states that he left everything to his "widow" in a will dated January, 1823. The only record we can find which might be for the right couple happened in Northiam, Sussex, where the marriage of George Hunger [sic] and Mary Ann Parsons is recorded on January 22, 1817. If this is the case, then their son, John, must have been born considerably before their marriage. [ back ]

21 St. Pancras, London, records the christening of John Greenwood Hanger, son of George Hanger and Mary Ann, on September 5, 1817. The omission of a separate surname for Mary Ann suggests that John was legitimate, which would mean Hanger and Mary Anne were married long before the dates mentioned in the previous note. If they weren't married, her surname would probably have been given. (In England a woman's own surname had no legal status after her marriage and was generally omitted from things like baptisms of children.) However, the information available is extremely contradictory and uncertain. Melville, 1:43. [ back ]

22 Cokayne, 3:370n(a). [ back ]

23 IGI records. There are two marriage records for a John Hanger marrying a woman named Mary within the possible time period, and no way to establish which, if either, is the right one. Amusingly, one of the possibilities has John Hanger marrying Mary Robinson at Saint Paul Covent Garden, Westminster, London on May 10, 1820. [ back ]

| Return to the Main Page | Last updated by the Webmaster on October 31, 2004 |