| [ Previous ] [ Next ] |

|

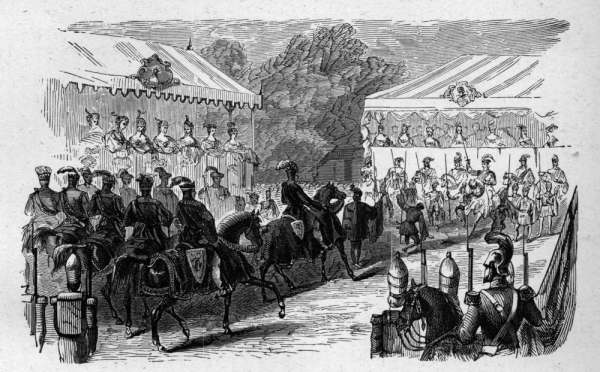

"After [the black Knights] had rode round the lists, and made their obeisance to the Ladies, they drew up fronting the white Knights; and the chief of these having thrown down his gauntlet, the Chief of the Black Knights directed his Esquire to take it up. The Knights then received their Lances from their Esquires, fixed their shields on their left arms, and making a general salute to each other, by a very graceful movement of their lances, turned round to take their career, and, encountering in full gallop, shivered their spears. In the second and third encounter they discharged their pistols. In the fourth they fought with their swords. At length the two chiefs, spurring forward into the Center, engaged furiously in single combat, till the Marshal of the Field...rushed in between the Chiefs, and declared that the Fair Damsels of the Blended Rose and Burning Mountain were perfectly satisfied with the proofs of love, and the signal feats of valor, given by their respective Knights; and commanded them, as they prized the future favors of their Mistresses, that they would instantly desist from further combat."1

John André penned this paragraph in 1778. What makes it unusual is that it is not a passage from a novel -- the jousting tournament it describes was neither historical nor fictional. It took place on May 18, 1778, on an estate just south of the city of Philadelphia. Among the fourteen "knights" who ritually jousted for the honor of such Fair Damsels as Peggy Chew and Rebecca Franks were André, Lord Cathcart, and Banastre Tarleton.

In the spring of 1778, Sir William Howe resigned his post as commander-in-chief of His Majesty's forces in America, turning his army and his problems over to Sir Henry Clinton. He sailed for England on May 24.2

Throughout the whole of the previous winter, the British had garrisoned in Philadelphia while the rebels lay roughly twenty miles away at Valley Forge. Both armies had massive supply problems, aggravated by the increasingly severe weather. In the wake of the battle of Germantown, Philadelphia was essentially under siege. Rebel raiders dealt severely with farmers caught bringing produce into the city, and army foraging parties leaving it needed to be large and very well armed. The rebels may have starved, but they did their best to ensure that their counterparts, not to mention the civilian population, shared the experience.

In November, Howe's forces were finally able to open up access to the city via the Delaware River, and life in Philadelphia began to improve. With the arrival of regular supply ships, their immediate concerns for survival faded and the British officer corps -- which included Banastre Tarleton, John André, Lord Cathcart and Charles O'Hara -- found themselves with an excess of time on their hands.

Their somnambulant Commander-in-Chief gave them nothing productive to do with that time, even though the enemy army lay tantalizingly close at hand. Bored by the prospect of a long garrison winter, frustrated by the enforced inactivity, they began to find creative ways to occupy themselves. Beginning in January, a group of amateur thespians, whose number included Tarleton, André and Cathcart, staged weekly plays in the renovated Southwark Theater. There were subscription balls, parties of various sorts, musical concerts, racing meets and cockfights. High-stakes card games brought financial ruin to a number of young officers, even driving a couple to suicide. The more intellectually minded could attend classes and study groups, which offered lessons in everything from languages to etiquette to music. That winter Philadelphia shimmered with a brilliant, if somewhat artificial, splendor for the social elite.

|

The culmination of that frenetic social "season" was a lavish going-away party thrown for Sir William Howe just before he departed for England. It was styled the "Mischianza" (or "Meschianza"), a made-up word derived from Italian terms for "mixture" or "medley," and it was to become both famous and infamous. "Famous" because it was staged on a scale that surpassed anything seen in America at the time; "infamous" because its critics -- rebel, Loyalist and British alike -- were quick to point out that this triumph worthy of Rome was staged to honor a departing general who had won neither a negotiated peace nor a military victory.3

There is no record of who came up with the notion of marking Howe's departure with a gala event. Legend attributes it to John André, but whether or not it was his original idea, he certainly became a driving force behind it, serving as planner, set designer and participant. He also became the event's chief publicist, thanks to a lengthy letter describing the event which was published in Gentleman's Magazine. (The letter was published under the heading "Copy of a Letter from an Officer at Philadelphia to his Correspondent in London" but André is universally accepted as its author.) This letter, and a second account also written by André, provide the most detailed descriptions of the Mischianza.4

Whatever his limitations as a Commander-in-Chief, Howe was extremely popular with his men. André may have been gilding the lily when he wrote "the knowledge he hath acquired of the country and people, have added to the confidence we always placed in [Sir William's] conduct and abilities" but it was with some truth that he added "I do not believe there is upon record an instance of a Commander in Chief having so universally endeared himself to those under his command." Somewhere between twenty-one to twenty-three of his wealthier officers each contributed £140 (a considerable sum) to stage "as splendid an entertainment as the shortness of time and [their] situation would allow." (A Hessian writer speculated that an additional £12,000 was spent on silks and other fine things.) From the group of subscribers, four officers were appointed managers for the event. Three are known for certain: Sir John Wrottesley, Charles O'Hara and John Montresor. The fourth manager is variously recorded as Sir Henry Calder or a Major Gardiner.5

Scheduled for Monday, May 18, the pageant was to be staged with a full Georgian love for pomp and spectacle. It drew its inspiration from a variety of entertainments held in England, including the festival celebrating Lord Stanley's marriage to the Duke of Hamilton's daughter. General Burgoyne had acted as master of ceremonies for that event, composing a play for the occasion, arranging fireworks and a masque, and attiring each guest in a theme-based costume. Another source of inspiration was a spectacular regatta which had recently been staged on the Thames. Such elaborate entertainments were very much a part of society in Britain or France, but staid and prudish Philadelphia had never seen their like. (Nor were they universally impressed. One Loyalist, James Parker, compared the display to the "pueril stories in the twopenny books.")6

The final program for the Mischianza was to include a procession along the Delaware, a stylized version of a medieval jousting tournament, an elaborate banquet, dancing, and a fireworks display. The site selected was the mansion of the late Joseph Wharton, which was in the Neck below the city, a location safely away from the city's defense perimeter. The Wharton house stood a convenient six hundred yards from the river, with spacious lawns and a landing place nearby for the flotilla of boats which would sail down from the city.7

Planning and preparations for the event took place on a remarkably brief schedule. Materials were located and purchased during the final two weeks of April, and given how badly the city's lumber supply had been ravaged for firewood over the winter, this was no mean feat. By the end of the month, the lawn of the Wharton estate began to undergo a transformation. The construction project itself became a source of entertainment. Grenadier officer John Peebles makes several mentions of the elaborate preparations. He dropped around once to check out what was going on, and planned to make a second visit, escorting some local ladies, but was prevented by rain.8

In addition to a tilting field big enough to give fourteen horsemen room to maneuver, "pavilions" had to be built for seating the spectators (very similar to modern bleachers, from the descriptions), as well as two triumphal arches with a connecting avenue. They also needed a building with a banquet hall and ballroom to accommodate more than 400 guests. The hall would be little more than a shell, its walls constructed of simple wooden and canvas panels on which André and Oliver DeLancey painted a faux marble finish and classically inspired decorations. Parker described it as simply "an arched roof covered with canvas & floored with plank." They borrowed the decorations, from looking glasses to candelabra, from local citizens. It was a remarkable achievement given the limitations of time and material -- and very much a last-minute one, since both Parker and Peebles record that building was still underway on the day before the pageant.9

The triumphal arches were decorated with martial themes, one naval (to honor Lord Howe), the other with army themes (for Sir William). These too were painted with classical and mythological themes, and had Latin mottos inscribed on their faux friezes. Sir William's column had a motto which translates as "Go, good man, whither your noble character calls you; go, and good luck attend you." Howe was going to need the luck, since he was headed home to face a Parliamentary inquiry into his conduct.10

Even the admission tickets were a work of art, the face engraved with "a shield, a view of the sea, with the setting sun, and on a wreath, the words Luceo discedens, aucto splendore resurgam ["I descend in light, and shall rise again in splendor"]. At their top was the General's crest, with Vive! Vale! All round the shield ran a vignette, and various military trophies filled up the ground." Individual invitations were inscribed by hand on the reverse side.11

May 18th dawned with daunting overcast, but the weather cleared by noon. By mid-afternoon, the day was "as favourable as the preparations were magnificent." The Mischianza began with some 400 guests gathering at Knight's Wharf in the north end of the city. From there, they boarded a flotilla of brightly decorated galleys and barges ("flat boats"), "lined with Cloth, covered with Awnings, and dressed out with Colours and Streamers in full naval pomp." This colorful procession proceeded slowly down the Delaware in a grand regatta, while most of the city's population assembled on shore to watch them row past. Prominent among the guests were Sir William, Lord Howe, Sir Henry Clinton, General Knyphausen, several other generals, and a number of local ladies. Preceding the procession were three barges carrying military bands. Further barges surrounded the main procession to keep off the "swarm of boats that covered the river from side to side." The crowds of spectators filled every available vantage point on shore or aboard the transport ships anchored along the river.12

The flotilla's arrival at the landing area at Old Fort, south of Philadelphia, was marked by 17-gun salutes from the warships Roebuck and Vigilant, which lay at anchor in the river. As the guests disembarked, they advanced along an avenue formed between two files of grenadiers backed by cavalry. A massed military band -- André says "all the bands of the army" -- led the procession, followed by the four managers "with favors of white and blue ribbands in their breasts" and the rest of the company. They proceeded to the tournament field, which was marked out on the lawn and lined with more troops, to the two pavilions built for the spectators.13

On the front seats of each pavilion were seated the ladies for whom the knights would joust. According to André, "The Ladies selected from the foremost in youth, beauty and fashion were habited in fancy dresses. They wore gauze Turbans spangled and edged with gold or Silver, on the right Side a veil of the same kind hung as low as the waist and the left side of the Turban was enriched with pearl and tassels of gold or Silver & crested with a feather. The dress was of the polonaise Kind and of white Silk with long sleeves, the Sashes which were worn round the waist and were tied with a large bow on the left side hung very low and were trimmed spangled and fringed according to the Colours of the Knight" who would "contend in their honour."14

Although several of these "fair damsels" were known for their beauty, there can be no doubt that they were selected more on the basis of politics than aesthetics. They were daughters of the foremost Loyal or neutral citizens of the city, leaders of fashion and society over the previous winter. Influential merchant David Franks' daughter Rebecca was among their number, as were Chief Justice Chew's daughters Peggy (who was championed by André in the joust) and Sarah. Ban Tarleton's Lady was sixteen-year-old Williamina Elizabeth Smith, daughter of another prominent Pennsylvania family.15

Peggy Shippen (the future Mrs. Benedict Arnold) and her two sisters had also been named to the company, but it is generally accepted that at the last moment their conservative father refused them permission to attend. The first account André wrote of the event (probably penned before it actually took place) lists the three Shippen girls among the attendees, but his second version, dated June 2, excludes them. Their father is said to have withdrawn his permission either after he'd seen the design of the "Turkish" dresses or because he came under pressure from a council of local Quakers to steer clear of such an immoral display. This idea seems to be documented only as a "Shippen family tradition," but the disparity between André's two lists supports it. On the other hand, a granddaughter of Sarah Shippen claimed that

"[M]y grandmother...never tired of telling me all the delight and glory of that memorable fête. I have heard so many particulars, that I am very sure she would have spoken of a deputation of her father's friends to prevent Miss Sarah and Miss Peggy from going in such costumes to the Mischianza -- and go they did....They were there...and one of them told me so."

So the point remains open to question.16

As soon as the guests were seated, a blare of trumpets heralded the entry of the upcoming tournament's seven white knights, "dressed in ancient habits of white and red silk, and mounted on gray horses, richly caparisoned in trappings of the same colours." Lord Cathcart, future colonel of the British Legion, was chief of these "Knights of the Blended Rose," flanked by two squires. André rode in as the third knight.17

A sketch of their costumes by André shows that calling them "ancient habits" was a bit of a stretch, but they were bright and fanciful. In his second account, André provides a more elaborate description:

"Their dress was that worn in the time of Henry the 4th of France: The Vest was of white Sattin, the upper part of the Sleeves made very full but of pink confined within a row of straps of white sattin laced with Silver upon a black edging. The Trunk Hose were exceeding wide and of the same kind with the shoulder-part of the Sleeves. A large pink scarf fastened on the right shoulder with a white bow crossed the Breast and back and hung in an ample loose Knot with Silver fringes very low under the left hip, a pink and white Sword belt laced with black and Silver girded the waist. Pink bows with fringe were fastened to the Knees, and a wide buff leather boot hung carelessly round the ankles: The Hat of white sattin with a narrow brim and high crown, was turned up in front and enlivened by red white and black plumes, and the Hair tied with the Contrasted Colours of the dress hung in flowing curls upon the back. The Horses were caparisoned with the same Colours, with trimmings and bows hanging very low from either ham and tied round their Chest. The Esquires of which the chief Knights had two and the other Knights one were in a pink Spanish dress with white mantles and sashes: they wore high crowned pink hats with a white and a black feather and carried the lance and Shield of their Knight. The lance was fluted pink and white with a little banner of the same Colours, and the Shield was silvered and painted with the Knights device."18

[more information] |

The knights circled the field, saluted their Ladies, then formed a line in front of their pavilion while their Herald advanced to the center of the field and proclaimed a challenge: "The Knights of the Blended Rose, by me their Herald, proclaim and assert that the Ladies of the Blended Rose excell in wit, beauty, and every accomplishment, those of the whole World; and, should any Knight or Knights be so hardy as to dispute or deny it, they are ready to enter the lists with them, and maintain their assertions by deeds of arms, according to the laws of ancient chivalry."19

Naturally, this challenge was promptly taken up by the second team, the black knights or "Knights of the Burning Mountain," who entered the lists with proper ceremony and formed an opposing line. Led by Captain Watson of the Guards, they wore black and orange silk laced with gold and rode black horses decked out in matching colors. Ban Tarleton, then a Brigade-Major with the cavalry detachment in the city, was the sixth of Watson's companion knights, taking part "not only with good humour, but with great spirit." (Being both red-haired and vain, Tarleton must have been appalled by the orange silk...)20

The roster of knights and damsels, as best it can be constructed from contradictory material, was21:

The Knights of the Blended Rose

Chief Knight, Lord Cathcart (17th Light Dragoons), in honour of Miss Auchmuty. On his right hand walked Captain Hazard (44th Regiment), and on his left Captain Brownlow (57th), his two Esquires. His device was Cupid riding on a Lion. His Motto, "Surmounted by Love."

1st Knight, Hon. Captain Cathcart (23d). Squire, Captain Peters. Device, a heart and sword. Motto, "Love and Honour." In his original account, André named Nancy White as Cathcart's damsel, but this was apparently changed at the last minute, due to the absence of the Shippen girls. If he represented a lady, her identity is unknown.

2d Knight, Lieut. Bygrave (16th Light Dragoons), in honour of Janet Craig. Squire, Lieut. Nichols. Device, Cupid tracing a Circle. Motto, "Without End."

3d Knight, Captain John André, in honour of Peggy Chew. Squire, Lieut. William André. Device, two Game-cocks fighting. Motto, "No Rival."22

4th Knight, Captain Horneck (Guards), in honour of Nancy Redman [or Redmond]. Squire, Lieut. Talbot (16th Light Dragoons). Device, a burning heart. Motto, "Absence cannot extinguish."

5th Knight, Captain Matthews (41st), in honour of Wilhelmina Bond. Squire, Lieut. Hamilton (15th). Device, a winged heart. Motto, "Each Fair by Turn."

6th Knight, Lieut. Sloper (17th Light Dragoons). Squire, Lieut. Brown. Device, a heart and sword. Motto, "Honour and the Fair." Sloper's lady was to have been Mary Shippen. Again, no replacement has been identified.

The Knights of the Burning Mountain

Chief Knight, Captain Watson (Guards), in honour of Rebecca Franks. Capt. Scott (17th) bore his lance, and Lieut. Lyttelton (5th) his shield. His Device was a heart with a wreath of flowers. Motto, "Love and Glory."

1st Knight, Lieut. Underwood (10th). Squire, Ensign Haverkam. Device, a Pelican feeding her young. Motto, "For those I love." Underwood's original lady was Sarah Shippen, but he ended up jousting for Nancy White.

2d Knight, Lieut. Winyard (64th). Squire, Capt. Boscawen (Guards). Device, a Bay-leaf. Motto, "Unchangeable." Winyard was to have jousted for Peggy Shippen. Who replaced her isn't known.

3d Knight, Lieut. Delaval (4th), in honour of Becky Bond. Squire, Capt. Thorne. Device, a heart, aimed at by several arrows, and struck by one. Motto, "One only pierces me."

4th Knight, Monsieur de Montluivant, (Lieut. of the Hessian Chasseurs,) in honour of Becky Redman. Squire, Capt. Campbell (55th). Device, a sunflower turning towards the sun. Motto, "Je vise à vous."

5th Knight, Lieut. Hobart (7th), in honour of Sarah Chew. Squire, Lieut. Briscoe. Device, Cupid piercing a coat of mail with his arrow. Motto, "Proof to all but Love."

6th Knight, Brigade-Major Banastre Tarleton, in honour of Williamina Smith. Squire, Ensign Hart. Device, a Light Dragoon. Motto, "Swift, vigilant, and bold."

A gauntlet was thrown and received, then the two lines of knights galloped towards each other and "shivered their spears." They made three more passes, twice with pistols, then finally once with swords. (They were all professional soldiers, but given their lack of real armor, one can't help but be amazed that no one ended up sliced open, or with slivers of shattered spear sticking out of one eye.) After the final pass, the two chief knights took center stage, engaging "furiously in single combat" until the Marshal of the Field, Major Gwynne, called a halt to declare that "the Fair Damsels of the Blended Rose and Burning Mountain were perfectly satisfied with the proofs of love, and the signal feats of valor, given by their respective Knights; and commanded them, as they prized the future favors of their Mistresses, that they would instantly desist from further combat."23

The knights saluted the spectators, then filed out through the first of the triumphal arches and formed up to each side of the avenue extending to the second arch. The whole company then proceeded past the knights and along the avenue, which was "300 feet long, and 34 broad...lined on each side with a file of troops; and the colours of all the army," From the garden, they ascended a flight of carpet-covered steps and entered the banquet hall. Here, the knights joined them and "on the knee received their favors from their respective Ladies."24

Justifiably proud of the achievement, André goes on to provide a luxurious description of the interior decor:

For these apartments we were conducted up to a ball-room, decorated into a light elegant stile of painting. The ground was a pale blue, pannelled with a small gold bead, and in the interior filled with dropping festoons of flowers in their natural colours. Below the surbase the ground was of rose pink, with drapery festooned in blue. These decorations were heightened by 85 mirrors, decked with rose-pink silk ribbands, and artificial flowers; and in the intermediate spaces were 34 branches with wax-lights, ornamented in a similar manner.

On the same floor were four drawing-rooms, with side-boards of refreshments, decorated and lighted in the same stile and taste as the ball-room. The ball was opened by the Knights and their Ladies; and the dances continued till ten o'clock, when the windows were thrown open, and a magnificent bouquet of rockets began the fire-works. These were planned by Capt. Montresor, the chief engineer; and consisted of twenty different exhibitions, displayed under his direction with the happiest success, and in the highest style of beauty. Towards the conclusion, the interior part of the triumphal arch was illuminated amidst an uninterrupted flight of rockets and bursting of baloons. The military trophies on each side assumed a variety of transparent colours. The shell and flaming heart on the wings sent forth Chinese fountains, succeeded by fire-pots. Fame appeared at top, spangled with stars, and from her trumpet blowing the following device in letters of light, Tes Lauriers sont immortals. -- A sauteur of Rockets, bursting from the pediment, concluded the feu d'artifice.25

The banquet itself began at midnight, at which time "large folding doors, hitherto artfully concealed, [were] suddenly thrown open, [revealing] a magnificent saloon of 210 feet by 40, and 22 in height, with three alcoves on each side, which served for side-boards. The ceiling was the segment of a circle, and the sides were painted of a light straw-colour, with vine leaves and festooned-flowers, some in a bright, some in a darkish green. Fifty-six large pier-glasses, ornamented with green silk artificial flowers and ribbands; 100 branches with three lights in each, trimmed in the same manner as the mirrors; 18 lustres each, with 24 lights, suspended from the cieling, and ornamented as the branches; 300 wax-tapers, disposed along the supper tables; 430 covers, 1200 dishes[.]" The fare included the finest fruit that could be obtained in America or the West Indies in spring.

Not bad, when one considers that it had all been brought together in less than a month, in wartime, in a city that was under siege.26

After supper, the company returned to the ballroom, and "danced & drank till day light when the Company retired to their respective homes highly pleasd with the Entertainment."27

"Pleased" most of the guests must have been, but their pleasure was not universally shared. In its aftermath, the Mischianza drew mixed reviews in diaries, letters and journals. The London Chronicle called it "nauseous" though in their case the dig was aimed at Sir William more than at the party itself. Contemporary authors such as Stedman held it up as a symbol for the failure and folly of Howe's (mis)management of the war. Others complained that it showed a lack of sense. Parker expressed that point of view in his journal:

"Had the Rebels got such a correction as they deserved, restored to their senses, and this been the feast of peace, it would have been very proper. But there are [those] who think it ill-timed, our Country by procrastination being involved in a french War."28

That opinion was expressed even more vehemently by his fellow-Loyalist Joseph Galloway:

"We have seen the same General, with a vanity and presumption unparalleled in history, after this indolence, after all these wretched blunders, accept from a few of his officers a triumph more magnificent than would have become the conqueror of America, without the consent of his sovereign or approbation of his country, and that at a time when the news of war with France had just arrived, and in the very city, the capital of North America, the late seat of Congress, which in a few days was to be delivered up to that Congress."29

Its justification was certainly open to question, but there can be no doubt that the Mischianza was participatory theater on a grand scale. Most guests must have enjoyed the party for its own sake even if they privately agreed with Parker's and Galloway's sentiments. The May 23 edition of the Pennsylvania Ledger carried a particularly glowing description, and Major Baurmeister called it "a spectacle one will never forget." Some three or four decades later, when John Watson was gathering material for a history of Philadelphia, he found that those old enough to remember the event recalled it with sentimental affection.30

John André penned his second, more intimate, account of the spectacle just before the British Army left Philadelphia, as a gift for Peggy Chew. It was essentially a hand-written "program book," decorated with watercolor sketches. She kept it and other souvenirs of their friendship all her life and passed them on to her daughter. By the end of the 19th century, the little booklet had come into the hands of her great-granddaughter, Sophie Howard Ward, who published the text in Century Magazine.

In her preface, Ward expresses the nostalgia with which the Mischianza had come to be remembered: "Faded and yellow with age, the little parchment vividly calls up before us the gallent young English officer, eager and full of keen interest, throwing himself with youthful ardor, with light-hearted seriousness, into this bit of superb frivolity....[W]hat woman will not wish that she had lived when men spoke and wrote with such earnestness these charming trifles?"31

No longer a symbol of bitter folly or useless extravagance, the Mischianza had descended into Philadelphia's folklore as it better deserves to be remembered: a brilliant example of the playful pomp and splendor which added lustre to the Georgian Age.

[Thanks to Don Gara for copies of the relevant pages from John Watson's Annals of Philadelphia.]

| [ Index ] | [ Previous ] [ Next ] |

1 "Particulars of the Mischianza in America," Gentleman's Magazine 48 (1778): 355. [ back ]

2 John W. Jackson, With the British Army in Philadelphia 1777-1778 (San Rafael, CA and London: Presidio Press, 1979), pp81-106, describes the problems the army encountered. Jackson's book is the most complete study I've found of the winter the British army spent in Philadelphia.. [ back ]

3 The word "Mischianza" supposedly derives from "mescere", to mix, and "mischiare", to mingle. (Jackson, p330n2) André spelled it "Mischianza" in the letter published in Gentleman's Magazine, then switched over to using "Misquianza" in the private account he wrote for Peggy Chew. Some contemporary letters and journals use "Meschianza" and occasionally one sees other variants such as "Mischeanza." [ back ]

4 Jackson, p235. Gentleman's, pp353-357. [ back ]

5 Gentleman's, p353. Jackson, p235. Carl Leopold Baurmeister, The Revolution in America: Confidential Letters and Journals, 1776-1784, of Adjutant General Major Baurmeister of the Hessian Forces, trans. and ed. B.A. Uhlendorf (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1957), p178. John Peebles, The Diary of a Scottish Grenadier, 1776-1782, ed. Ira D. Gruber (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1998), pp181-182. [ back ]

6 Robert McConnel Hatch, Major John André, A Gallant in Spy's Clothing (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), p98. The Parker quote is in Jackson, p238. [ back ]

7 André, John and Sophie Howard Ward, "Major Andre's Story of the 'Mischianza,'" The Century; A Popular Quarterly 47 (1894): 688. [ back ]

8 Peebles, p180, 181. Jackson, p236. [ back ]

9 Gentleman's, p355-356. Ward, p690-691. Jackson, p236. John F. Watson, Annals of Philadelphia, and Pennsylvania, in the Olden Time, ed. Willis P. Hazard, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: Edwin S. Stuart, 1905), 2:292. Watson interviewed one of the Mischianza belles, Becky Redmond, in her old age, and she confirmed André's comments on the building material: "[The] Sienna marble...on the apparent side walls, was on canvas, in the style of stage scene painting." She also assured him that all of the borrowed decorations had been returned without harm. Extracts from Parker's journal appear in Catherine S. Crary, The Price of Loyalty; Tory Writings from the Revolutionary Era (New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1973), p316. [ back ]

10 Gentleman's, p355. Ward, p688. Morris Bishop, "You Are Invited to a Mischianza," American Heritage (August 1974): p71. [ back ]

11 Gentleman's, p353. Jackson, p239, shows a picture of one of the tickets. [ back ]

12 John Montresor, "The Montresor Journals," ed. G. D. Scull, Collections of the New-York Historical Society for the Year 1881 (New York: Printed for the Society, 1882), p492. Gentleman's, p353. Peebles, p181. Ward, p687. [ back ]

13 Gentleman's, p353-354. Peebles, p181. [ back ]

14 Gentleman's, p354. Ward, p688. Peebles, p182 [ back ]

15 Gentleman's, p354-355. Ward, p684. Williamina Smith, described as a "bright, sprightly girl" married Charles Goldsborough of Maryland after the war, and died in childbed in 1790, per Horace Wemyss Smith, "Descendants of the Rev. William Smith, D.D.," Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 4 (1880): p380. [ back ]

16 The Shippen family tradition is recounted several places, including Lewis Burd Walker, "The Life of Margaret Shippen, Wife of Benedict Arnold," The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 24 (1900): 427. A letter from Sarah Shippen's granddaughter, Mrs. Julius J. Pringle, is quoted in a debate on the issue in the Notes and Queries columns of Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 23 (1899): 119-120, 412-415, under the heading "Did Peggy Shippen And Her Sisters Attend the Meschianza?" [ back ]

17 Gentleman's, p354. Peebles, p182. [ back ]

19 Gentleman's, p354. Peebles, p182 [ back ]

20 Gentleman's, p354-355. Peebles, p182. Ward, p689. Martial Biography, Or Memoirs Of The Most Eminent British Characters Who Have Distinguished Themselves Under The English Standard By Their Splendid Achievements In The Field Of Mars... (London: Printed by James Cundee, Ivy-Lane, For Thomas Hurst, Paternoster-Row; J. Harris, St. Paul's Church-Yard; and J. Wallis, Ludgate-Street. 1804), p326. [ back ]

21 Gentleman's, p354-355. Jackson, p243-244. [ back ]

22 William André was John's younger brother. [ back ]

23 Gentleman's, p355. Peebles, p182 [ back ]

24 Gentleman's, p355-356. Peebles, p182, says the avenue was "lined with 1 officer & 20 men from each Regt. & their respective Colours[.]" Ward, p690. [ back ]

25 Gentleman's, p356. Peebles, p183, describes the room as "100 feet long painted & decorated in a very showy manner with numbers of lights & looking glasses." [ back ]

26 Gentleman's, p356. Baurmeister, p178. [ back ]

27 Peebles, p183. Gentleman's, p356. [ back ]

28 Chronicle quoted in Jackson, p249. He also quotes from other critical reports, including Stedman's. [ back ]

29 Galloway quoted in Winthrop Sargent, The Life and Career of Major Andre (Boston: Tichnor and Fields, 1861), p180. [ back ]

30 The Pennsylvania Ledger article is printed in Frank Moore, ed., Diary of the American Revolution from Newspapers and Original Documents, 2 vols. (New York: Charles Scribner; 1858), 2:52-56. Watson, 2:290. Baurmeister, p178. [ back ]

| Return to the Main Page | Last updated by the Webmaster on January 30, 2004 |