|

|

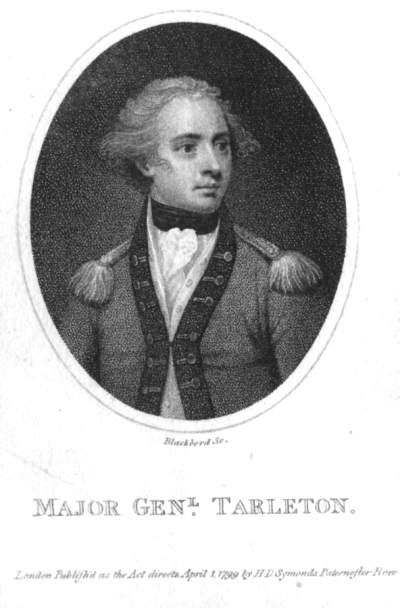

This engraving of Tarleton was issued around the time he served in Portugal. A slightly different version than that which is shown here was printed in Martial Biography, Or Memoirs Of The Most Eminent British Characters Who Have Distinguished Themselves Under The English Standard By Their Splendid Achievements In The Field Of Mars ... (London, 1804), but it seems to have been issued previously as a print.

|

The text beneath this version of the image reads "Blackberd Sc.," and below Tarleton's name is "London Publish'd as the Act directs April 1, 1799 by H.D. Symonds Paternoster Row." The image size is roughly 5.5 x 3.5 inches. (The version printed in Martial Biography is slightly smaller, with different typesetting on the text.)

It is obviously connected to the

pen-and-ink sketch which shows up frequently in 19th

century coverage. It may be the source for the sketch, or they may both have been taken from a

third, unknown image.

It is obviously connected to the

pen-and-ink sketch which shows up frequently in 19th

century coverage. It may be the source for the sketch, or they may both have been taken from a

third, unknown image.

If it really does show Tarleton as a major-general, then obviously it wasn't painted by the long-dead André. However, both the youthfulness of the face (Tarleton turned forty-five in 1799) and the style of the uniform suggest that the miniature was painted considerably earlier. The uniform style is closer to that of the Revolution than the beginning of the 19th century. So the question of its artist, and even its original form, remains unanswered.

The Tarleton mini-bio in Martial Biography was one of the primary source documents for his entry in the Dictionary of National Biography. It was published the year he turned fifty, and being included must have pleased him enormously, since he shares its pages with such luminaries as the Duke of Marlborough and General Wolfe, (as well as such contemporaries as Earl Cornwallis and Lord Rawdon.) The text of the article is printed below.

[p326] Tarleton, (Banastre)...Major-general Tarleton is the second son of Mr. John Tarleton, an eminent merchant of Liverpool. He was born in the year 1755. His father destined him for the profession of the law: and after finishing his education at Oxford, he was admitted a student of the temple, London. But the repetitions of jurisprudence had no charms for our hero: and the American war breaking out, he turned his attention to arms, and entered as a cornet in the first regiment of dragoon guards, April 20, 1775. He remained in this commission nearly two years, when, wearied with that inactive life, he embarked with some reinforcements for America, where; for his activity, courage, and abilities, he was promoted by sir William Erskine, then general of cavalry, to the rank of brigade-major; in which situation, by his good horsemanship, he recommended himself to the knowledge of all the officers of the staff in general; and he acquired that particular knowledge which qualified him for the prosecution of those petty skirmishes which usually fall to the lot of a leader of light troops. He continued a brigade-major during the whole of the year 1777, and part of 1778 with the chief Pennsylvania army. It could not be said, however, that the cavalier and his horse were idle: equestrian exercises with his brother officers occupied his leisure hours, while pent up in the lines of Philadelphia. A new commander in chief was however about to be appointed, whose disposition inclined him to cut out more active and useful work to such men as the aspiring Tarleton. At the Mischianza, however, a fete instituted in compliment to sir William Howe on returning home, as was pleasantly said an unconquered knight, our military adventurer took a part in it, not only with good humour, but with great spirit also. In the mock touraments he acted the part of the black champion to the fair damsels of the Burning Mountains. The trophy he bore with the motto "swift, vigilant, and bold," were adopted by him with intent to characterize his views, and the energy of his mind; and lest it should be imagined that his [p326] devotion to Mars might leave him no desire to pay his vows to Venus, he chose a name for his squire appropriate to such a cautious design. But as this was not a voyage to the island of Cythera, sacred to dalliance, but to the continent of America, then in rebellion against the mother-country: not a contest with metaphorical arrows, said to be tipt with gold and silver, but a warfare carried on by the fatal sword, and more destructive ball; we shall in our sketch pass over those deviations, those wanderings from the common track of his professional duty, and leave them to be spoken of by the frequenters of Cyprian haunts and followers of pharo banks; places of dissipation, and we may say of destruction, but too much resorted to by men who profess to be actuated by the most noble principles....When the army, under the command of sir Henry Clinton, left Philadelphia for New York in 1778, captain Sutherland, one of his aids-de-camp, had permission to raise a corps under the denomination of the Caledonian volunteers, who gave him the rank of major-commandant. This corps was relinquished in favour of the gallant lord Cathcart, a young nobleman, who had distinguished himself in his excursions in Pennsylvania. Upon the promotion of this latter officer the corps was new modelled by being made up into a legion of light-cavalry, with infantry attached to it, and called the British Legion. Of this newly re-organized body of troops, brigade major Tarleton was appointed commander, with the local rank of lieutenant-colonel. A promotion so rapid in preference to many other officers of much older standing, could not fail to give some umbrage, and especially attract the eye of those captious judges who are always ready to animadvert upon the least departure from established usage. Colonel Tarleton was however countenanced by the officers at the head of the army, and therefore he felt satisfied he should silence the tongue of envy by a zealous execution of his duty. In the beginning of the year 1778, a new regiment, the seventy-ninth, under the name of the royal Liverpool volunteers, was raised, in which, from the circumstance of its being recruited in his native town, and in some measure by the influence of his friends, he was appointed eldest captain, and his commission, dated with those of the staff, before that of every other battalion officer. This regiment embarked for the West-Indies under major-general Hall, and as captain Tarleton was on a distinct service in America, he was allowed an over-slaugh, and to draw his regimental pay as if in Jamaica. The moment for the display of his energy on the American theatre was now arrived. The campaign for the year 1780 was now planned in the councils of the British commanders in New York. The one of the preceding year had closed much to the disadvantage of the Americans. The defeat of the French naval commander, and his expulsion from Georgia, together with the spiritless condition of the continental troops and Militia under Washington, had occasioned a resolve to carry the British arms to the southward. An expedition to Charlestown was accordingly undertaken, and Colonel Tarleton embarked with sir Henry Clinton early in the season. On the 12th of February the army was safely landed on the islands in the vicinity of Charlestown; and from thence proceeded to the banks of Ashley's river, between [p327] which, and Cooper's river, that town is situated. At the close of the month of March the whole force crossed Ashley River, and broke ground within eight hundred yards of the enemy's works, in the night of the first of April. Various obstacles being overcome, and admiral Arbuthnot having taken possession of the harbour in spite of the vigorous fire from Fort Sullivan, the general and admiral summoned the town to surrender, but the American general, Lincoln, who commanded there, answered, that he would defend it to the last extremity: the batteries were therefore opened on the ninth of April, and approaches made within little more than four hundred yards of the town. These proceedings made it necessary to cut off all communication between the town and country; for which purpose a detachment of chosen men was formed; colonel Tarleton with a body of cavalry, and major Fergusson with twice the number of infantry were fixed on; the whole to be commanded by colonel Webster. The enterprize was accompanied by numerous difficulties: they had rivers to cross, and a strongly posted enemy to dislodge; an enemy too, greatly superior in cavalry. It was at this corps the efforts of the detachment were principally aimed. By the dexterity and bravery of our hero it was surprised and totally defeated. This obstruction being removed, the detachment advanced into the interior of the country, and seized all the principal passes, by which means the town was completely invested, and the army enabled to proceed on the siege with additional vigour and security....The Americans were greatly alarmed at these proceedings, and took uncommon pains to repair their loss of cavalry, which, with great industry and expence, they were able to effect, as horses had been dispatched from very considerable distances. But no sooner was intelligence of their approach obtained, than colonel Tarleton was ordered to attack them; and he executed his commission with so much success and speed, that almost the whole corps was either taken or destroyed, and all the horses fell into the hands of the victor. Charlestown being reduced, the neighboring provinces were greatly discouraged, not doubting but the successes of the British arms under sir Henry Clinton would be improved to the utmost. The enemy therefore collected, with all possible speed, a force sufficient to make a temporary stand till an adequate army could be formed. Detachments of Americans were drawn from various parts to the borders of North Carolina, where it was naturally expected the motions of the British army would next be directed. The enemy was posted at a place called Warsaw, on the boundary line which marked north and south Carolina, at a hundred miles distance from earl Cornwallis. His lordship, no sooner heard of the Americans having assembled this new army, than he marched up the banks of the river Santae, and colonel Tarleton was again selected to spring forward with a chosen body of men, and to attack them before they could be re-inforced. He advanced with such rapidity, according to his usual custom, viz a hundred miles in forty-eight hours, that he reached them the third day of his march; he proposed to them the same terms as had been granted to the garrison of Charlestown, but they refuse them; upon which colonel Tarleton fell upon them with so much [p328] skill and courage, that by far the major part of them were either killed in the action, or wounded and made prisoners. Lord Cornwallis, in the account he gives to Sir Henry Clinton of his proceedings, dated June 2, 1780, says, "In my letter of the 30th of last month, I enclosed a note from lieutenant-colonel Tarleton, wrote in great haste from the field of action. I can only add the highest encomiums on his conduct, and it will give me the most sensible satisfaction to hear that your excellency has been able to obtain for him some distinguished mark of his majesty's favor." And in the commander-in-chief's account of the same action, to lord George Germain, of the 5th of the same month, and published with the former in the London Gazette, his excellency says, "Your lordship will observe, that the enemy's killed, wounded, and taken, exceed lieutenant colonel Tarleton's numbers with which he attacked them." This was the third victory obtained by the British cavalry, commanded by this enterprising young officer. The numbers he had with him in every one of these engagements, were inferior to those of the enemy; but they were chosen men, both for their management of their horses and expertness in the use of their arms. The consequence of this last affair was important to the interests of the British cause, as it decided, for that time at least, the fate of all Carolina. Sir Henry Clinton was succeeded in the command by lord Cornwallis, who observing the vigorous military preparations of the Americans, found it would require the utmost exertions of his talents to oppose them. And he fixed upon Camden for the centre of his military operations. General Gates, and Baron Kalbe, (a German officer of merit) were advancing to oppose his progress. The appearances were truly disheartening to men of less resources of mind than those at the head of this part of the British army. Upon the appearance of the American forces under general Gates, on the confines of South Carolina, many of the inhabitants repaired to him, regardless of their assurances of fidelity, and two whole battalions raised for the British service also went over to the enemy. In this state of affairs no time was to be lost: the post at Camden was much exposed, the main body under Gates pressed it on one side, and a strong detachment under general Sumpter was endeavoring to cut off its communications with Charlestown, to all which may be added, that the whole country beyond Camden had declared in favor of the American general. Such were the circumstances, when Earl Cornwallis resolved to attack Gates at the head of near six thousand men, while his own did not amount to a third of that number; but he relied on the goodness of his little army. On the 15th of August, 1780, he advanced to give battle to the Americans, encamped at twelve miles distance; and at the precise time the latter marched to attack the post at Camden. They met on the road in the night, they fought next morning; the ground was advantageous to the smaller army: after an obstinate resistance of three quarters of an hour, the Americans were thrown into confusion, and forced to give way in all directions. The cavalry completed the victory, over an enemy so very superior in numbers, pursuing the fugitives as far as Hanging Rock, a distance of twenty-two miles. On this occasion Lord Cornwallis, in his dispatches says, "the capacity and vigour of Lieutenant-colonel [p329] Tarleton, at the head of the cavalry, deserves my highest commendation." On the morning of the 17th he was, by lord Cornwallis, detached with the legion cavalry and infantry, and corps of light infantry, in all about three hundred and fifty men, with orders to attack general Sumpter, who was advancing down the Wateree with near a thousand men; the like orders were given to Lieutenant-colonel Turnbull and major Fergusson. Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton had the good fortune to reach him first, and executed the service he was sent upon with his usual activity and military address. He obtained good information of Sumpter's movements; and, by forced and concealed marches, surprised him in the middle of the day of the 18th of August. The place of attack was the Catawba Fords, where he totally destroyed or dispersed his detachment, then consisting of seven hundred men, killing one hundred fifty on the spot, and taking two pieces of brass cannon and three hundred prisoners, besides forty-four waggons. He likewise retook one hundred British prisoners, who had fallen into the enemy's hands at the action of Hanging Rock, and others in escorting some waggons from Congarees to Camden: he also released one hundred and fifty British militia and friendly country people, who had been seized by the Americans. This double defeat of the enemy, it might have been supposed, would extinguish their hope of ever regaining possession of South Carolina. It was however, otherwise; for no sooner had the enterprising Fergusson met with his death, and his party with a defeat on King's mountain, then their hopes revived, and new means were taken for the total expulsion of the British. General Sumpter, who had been handled so roughly in the two late affairs, had not lost all relish for a further trial of skill. The Americans considered him as one of their most active officers, and lost no time in assembling a considerable body of men to put under his orders; he proceeded with them towards the British posts in the upper country of South Carolina, with an intent to surprise them. Lord Cornwallis was timely informed of his movements, and dispatched Tarleton to give him the meeting, and prevent him from executing his design. Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton on this new occasion surpassed, if possible, any thing he had hitherto done, in respect to the celerity of his motions. He penetrated a large extent of country, and came up with Sumter just as he was preparing to pass the Ennoree, and with all the expedition he could use, he was obliged to leave his rear guard behind, every man of whom was either killed or taken. Sumpter fled with the utmost precipitation, his pursuer overtook him, by which he was compelled to make a stand on the banks of the Tyger, or leave the British to press as before on his rear. He was partly induced to make this stand by the information that Tarleton, in the eagerness of his pursuit, had left his infantry some miles behind, and that his whole force did not amount to more than three hundred men: not doubting to put this handful to the rout before it was joined by the main body, he drew up his party, of more than a thousand men, on an advantageous ground; but colonel Tarleton, notwithstanding his inferiority, attacked him with such incredible vigour, without waiting for all his infantry to come up, that he broke them; and compelled [p330] them to cross the river in the utmost confusion. In this splendid action general Sumpter was dangerously wounded, three of his colonels were killed, and one hundred and twenty men killed, wounded, or taken prisoners. Earl Cornwallis, in his dispatches of Dec. 3, 1780, says, "it is not easy for Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton to add to the reputation he has acquired in this province: but the defeating one thousand men, posted on very strong ground, and occupying log-houses, by one hundred cavalry and eighty infantry, without the assistance of any artillery, is a proof of that spirit and those talents which must render essential service to his country." Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton was next ordered to advance with speed to the relief of Ninety-six, with orders to clear that part of the country of the American parties which infested it, and especially of that under colonel Morgan, a brave and distinguished officer. He came up with and attacked colonel Morgan at eight o'clock in the morning, of the 17th January, 1781, and obliged him to retreat to Broad river, which being impassable from the great rain, an engagement became unavoidable, and the champions of the two powers were about to put their abilities in what is called petit guerre, to the test. Morgan was convinced, that were he defeated, his whole party must be either taken or destroyed, and that the event of the campaign depended on his success. Animated by these motives, he made every disposition in his favor which the nature of the ground admitted. He formed his party in two divisions: the first, composed of militia, occupied the front of an open wood; the second was drawn up in the wood itself, and consisted of the marksmen and best troops. Colonel Tarleton drew up in two lines, placing his infantry in the centre of each, and his cavalry on the flanks: he attacked and routed the militia that fronted him, pursuing them into the wood, with air they fled with precipitation. This defeat being expected by the American colonel, he provided against it accordingly. On the first line giving way, he directed the second to open to the right and left, and extend along the wood. A way being opened for the fugitives, their pursuers were suffered to follow them, till they were entangled in the wood, when, on a signal given, they were assailed on both sides with a terrible discharge of rifle pieces from behind the trees, almost every shot of which took effect. They were confounded by this attack from an unexpected and almost invisible enemy. The greatest part of the infantry were cut to pieces, and the seventh regiment lost its colours; two three-pounders also fell into the enemy's hands. Colonel Tarleton, however, did not lose his presence of mind by this interruption of his successes, for he assembled fifty of his choice cavalry, who, spirited up by the intrepidity of their leader, charged and repulsed an hundred horse under colonel Washington. On the 2d of February, he had the good fortune to defeat a corps of the enemy's militia, assembled under colonel Pickering, near the Catawba. On the 2d of March also he fell in with a considerable number of the enemy, detached from the army under general Green, he routed them and drove them into the main body, who apprehending the approach of the whole British army, fell back to a more secure position, till reinforced by the continental regulars that were daily [p331] expected. The last action fought by this brave officer in America, was the battle of Guildford, which took place on the 15th of March, in the same year. Lord Cornwallis set forward to meet general Green, who was reported to be advancing full speed upon him. Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton falling in with the advance parties of the enemy, charged them with his accustomed spirit, killed several of them, and drove the rest back upon the main body, which was drawn up on a rising ground near the town of Guildford. The smallness of the earl's force admitted only of being formed in two lines. His right wing was commanded by general Leslie, and his left by colonel Webster, and colonel Tarleton was left with a body of reserve and the cavalry. The battle began about two in the afternoon, when after several discharges on both sides, the superiority of the Americans in number enabled them to outflank the wings of the British army, the second line was obliged to unite with the first, in order to form an equal length of front with the Americans. Notwithstanding the disparity of numbers, the enemy were not able to withstand the vigorous attack made upon them, but were broken. They however rallied again, and put British courage and discipline to a full trial. The second battalion of guards, under major-general O'Hara, distinguished themselves, and drove the enemy into a wood in the rear. Other divisions of the British army made their way through the wood and charged as they came up; when lieutenant-colonel Tarleton, with the cavalry, which he had been ordered to keep compact till an opportunity for a decisive stroke occurred, with a resolute onset fell upon the enemy, and terminated one of the most bloody and hard contested conflicts fought in America. The enemy's loss in killed and wounded was computed at near two thousand, besides the total loss of their artillery and ammunition. Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton was wounded in this action. The noble lord, in giving an account of the battle to the American secretary of state, says, "Lieutenant-colonel Tarleton's good conduct and spirit in the management of his cavalry was conspicuous during the whole action." Thus have we curiously traced the military career of an officer, whose frequently repeated exploits justified the partiality shown him by the commanders of the armies on the American station, and which, in all probability, occasioned him to be sent in 1799, on an important command in aid of our ally, the crown of Portugal. On the 15th of July, 1780, while making the campaign in America, he was promoted to the rank of major in the army, and to that of lieutenant-colonel the 15th of June, 1781. On the 18th of Nov. 1790, he was included in the list of colonels, and on the 3d of Nov. 1794, he was made a major-general. On the reduction of Tarleton's dragoons, in 1783, the lieutenant-colonel commandant and other officers were placed on half-pay. Gen. Tarleton has lately been appointed col. of the princess of Wales's regiment of fencible cavalry. He has been twice chosen to represent the town of Liverpool in parliament; as member for which he has often distinguished himself in the defense of the rights of his country; and displayed his superior and useful knowledge of military subjects.

| Return to the Main Page | Last updated by the Webmaster on January 30, 2004 |