THE MAN WHO BROKE A THOUSAND CHAINS

(Click on anything in color to view photograph or image)

The frail bespectacled man stared out the window as the morning light

struggled to break through the overcast skies. He kept his collar

pulled up and his hat pulled down as the bus pulled into Newark's

Greyhound Terminal. "Last stop! Everyone off!" announced

the driver as the vehicle came to a stop. It was the 6th of

September, 1930, and Robert Elliot Burns was still in a state of

shock. How could his happy and content life of last year been so

transformed. He now would be forced to live a life of fear and

desperation, searching for justice and peace. Thus begins the

incredible saga of a man who was the subject of two books and the

inspiration for two feature films. From this time forward, he was

destined to be known as "the man who broke a thousand chains!"

THE MAKING OF A CRIMINAL

Robert Burns did not have an unusual childhood. He was born on May 10, 1892, in Queens, New York, and, except for a health scare when he was ten years old, his early life was uneventful. His struggle with pneumonia, however, caused him health problems for the rest of his life. He was an industrious and intelligent youth, and his closest friend growing up was his brother Vincent, a year and a half-younger then him. Although he was naturally friendly and outgoing, he was given to bouts of depression. By the age of fifteen, he had had enough of school and began working as a bookkeeper at a nearby office.

Robert seemed happy at his work, and was successful for a number of years. However, when Vincent left to attend Penn State College, Robert caught the "wandering fever." He left home with only a suitcase, with no idea where his travels would take him. No one had heard from him for eighteen months when he suddenly reappeared with a few dollars in his pocket and a hundred tales of adventure to tell.

When the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, Robert Burns was 25 and finally seemed to have settled down. He was a successful business accountant, and his prospects were bright. However, like many other patriotic Americans, he did not hesitate to enlist in the armed forces. He was assigned to the Medical Detachment of the 14th Railway Engineers and was shipped to the Front in France in the summer of 1917. He stayed at the Front for the rest of the war, tending the sick and wounded, and burying the dead. His biggest struggle was the fight to conquer the physical and mental strain of war, a fight he was destined to lose.

The "War to End All Wars" ended in November, 1918, and Burns was shipped home to America. He arrived back at the family house in May, 1919, and his family could immediately sense the difference in his personality. Gone was the happy and fulfilled young man who had left the year before, and now his occasional bouts of depression had become more and more prevalent. Both his spirit and health were broken, and he was suffering from what was then called "Shell Shock." His parents and brother tried to help, but without his cooperation, there was little they could do. It did not help that with the end of the war and the return of the service man from Europe there came an economic downturn. Like many other veterans, Burns could not find a steady, well paying job, and when he did find work, his newfound bitter attitude prevented him from keeping it. He would often disappear for weeks at a time with telling anyone where he was. Finally, in January, 1922, Robert Burns had had enough. He appeared at the seminary his brother Vincent was attending in Manhattan (he was now studying to be a minister), and after borrowing $50.00, he faded into the night.

THE CRIME

Confused and depressed, Robert Burns began to wander south. The borrowed $50.00 did not last long, and he was quickly reduced to living the life of the "hobo," illegally riding the freight trains and searching for menial jobs to subsist. After about a month he found himself outside of Atlanta, Georgia, hungry and in need of work. He accepted an offer from a fellow vagrant to help with an easy job, but the job turned out to be an armed robbery. Burns always claimed he had no idea what the fellow planned, and was forced at gunpoint to abet the crime. The total take was $5.80, and all three accomplices were captured within minutes.

Burns plead guilty to the crime of robbery on the advice of his court appointed attorney. He made an impassioned speech to the judge, outlining his early life, service to his country during the war, and his recent misfortunes. The judge was not impressed and sentenced Burns to 6 to 10 years at hard labor. Burns would soon learn what "hard labor" meant in the State of Georgia.

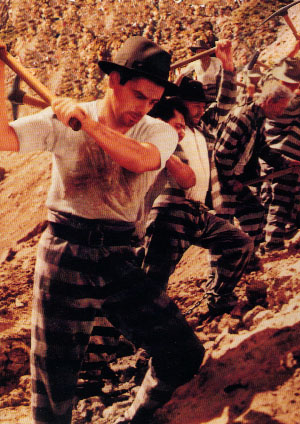

THE CHAIN GANG

The chain gang was not a peculiar Georgia institution. Chain gangs existed throughout the United States in the 1920's, especially in the Southern part of the country. The premise behind them was simple. A prisoner would be both punished and hopefully transformed by hard work. In addition, the gangs would be self-sufficient, with the money made by the prisoners' labor used to pay for their food, lodging and guards. But although Georgia was not the only state with chain gangs, it probably had the most corrupt and brutal ones.

According to Burns' later account, when he arrived at the Fulton County chain gang he was shocked by what he saw. There were no large, stone buildings, no tall walls, and no jail cells. Instead he found a few dilapidated wooden buildings surrounded by a wire fence. His first stop was the blacksmith's shop, where Burns learned why they were called "chain" gangs. He was fitted with a chain attached to each ankle with a shackle, to which another chain was attached in the center with a large ring on the end. The chains prevented Burns from taking full steps and he was forced to "shuffle" forward. He also had to hold the ring and carry the other chain forcing him into a slouching position while he walked. Robert Burns was now officially a member of a Georgia chain gang.

The daily routine at the Fulton County Chain Gang never varied. Breakfast was served at 3:30am every day. The food was bland and often spoiled, and there was barely enough to keep a man alive. The men were then trucked, or marched, out of camp in work gangs to a nearby quarry, highway, or railroad bed, and the workday would begin. The work was brutal and unending, especially in the hot Georgia sun. No cessation of labor was tolerated. The slightest pause would act as a signal to the sadistic guards to start a physical and verbal thrashing of the malingerer. A prisoner even needed to ask the guard's permission to wipe the seat from his brow. The work continued until 6:00pm, with only a fast break for lunch.

When the men arrived back in camp it was time for dinner, which was basically the same as breakfast and lunch. Only on special occasions were the men given the time to bath, and even then only the lucky few that washed first were able to do so in clean water. After dinner the prisoners would return to their barracks, and then the most terrifying part of the day began. It was time for the beatings.

Each and every day one or two men from each work crew were identified by the guards as not having worked hard that day. They were taken to another room and within earshot of the other convicts were beaten with a leather strap six feet long, three inches wide and one-quarter inch thick. The prisoner chosen would plead for mercy, but the sound of the strap would drown out his pleas and soon only his screams and the sickening crash of the strap was all that could be heard. As Burns wrote, "Ten licks and the convict, half fainting or perhaps unconscious, was stood on his feet - blood running down his legs, and one of the guards carried or led him back into the sleeping quarters. The next got the same dose."

Burns quickly realized he would never survive his sentence on the chain gang. His family had been told that for a "fee" of $2,000.00 he could be eligible for parole in one year, but they were not in any position to raise that amount of money. He decided his only hope was escape. "Not that I wanted to cheat justice," he wrote, "but six years was plain vengeance and also complete destruction. Well, I'll die out trying to run out!"

THE GREAT ESCAPE

After a few weeks, Robert Burns was transferred to the Campbell County chain gang, where conditions were worse but the possibility of escape was better. The work crews were smaller and the guards were fewer. He knew he could not escape in chains so he needed to find a way to remove them without detection. Enlisting the help of a fellow convict, Burns had him bend the shackles attached to his ankles with a sledgehammer when the guards were not looking. The slightest movement or missed blow would have caused a broken ankle and detection. It took many painful blows, but finally they were bent enough to allow him slip them off.

Burns needed to wait for the perfect day to make a run for it. He chose June 21, 1922. On that day he was on a work crew with eleven other prisoners, two guards and three bloodhounds. He asked one of the guards for permission to answer the call of nature, and when it was granted he went behind a nearby bush for privacy. He had only minutes to remove the chains and gain as much of a head start as possible, so he acted quickly. He was only a few yards away when he heard the guard yell for him to hurry. He knew when he did not immediately answer his escape would be detected, so he broke into a full run through the woods. Buckshot from the guard's shotgun sprayed all around him, but he kept running. Soon he could hear the sound of the dogs getting nearer, and expected to be torn apart when they caught him. When they finally overtook him he was pleasantly surprised to discover that he could control the dogs by acting as their master. In fact, after a brief pause the dogs began to run with him barking and seemingly enjoying the exercise.

After running for seven hours with little rest and stealing a change of clothes from a clothesline, Burns came to a wide stream. Bidding farewell to his new found canine friends, he swam across and soon came to a paved and busy road. He decided to hitch a ride in any direction he could. He knew he had to "get off the ground" before he was seen and recaptured. With luck and guile, Burns made his way north by car, foot and train. Finally he arrived in Chicago.

Robert Burns' first job in Chicago was as a manual laborer in the famous stockyards. He earned what he would have considered slave wages just a year earlier, but after his life on the chain gang, "It was all a man could want." He rented a room at a house on Ingleside Avenue from Mrs. Emelia Del Pino Pacheo (Emily), a forty year old divorcee, who owned the house and lived there with her mother.

Burns soon became close to Emily and her mother, and within a few months Emily fell madly in love with him. He did not return her feelings of affection and he told her so, but they continued to live together. Eventually they began renovating apartments in the neighborhood and renting them out for a profit. It was around this time that Emily discovered Burns' secret when she discovered a letter from his brother Vincent, addressed to him, discussing his escape. She swore to keep his secret and they remained living together for the next four years. However, in the summer of 1926 her attitude changed and she demanded that he marry her. She threatened to turn him over to the police if he refused. Perhaps it was fear, or perhaps it was gratitude for all her help, or maybe he just felt he would never truly fall in love again, but Burns finally agreed to wed.

The couple's real estate enterprise continued to be profitable, and Burns decided to pursue a dream of his, publishing a local business magazine. It took months and months of hard work and perseverance, but eventually the "Greater Chicago Magazine" became a success, and Burns became a much sought after speaker for civic, business and social organizations. At these meetings he met many important people, and made many influential friends.

Although he continued to live with Emily, their marriage had collapsed and he was rarely home. When he was home they avoided each other. In February, 1929, Burns met an attractive taxi dancer, waitress and music student named Lillian Salo. It was love at first sight. Within a month they had decided to marry, but of course there was one problem.