|

|

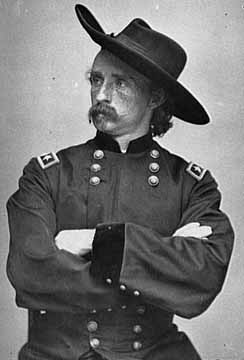

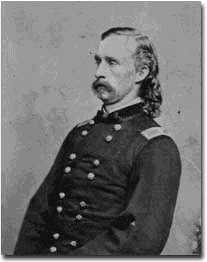

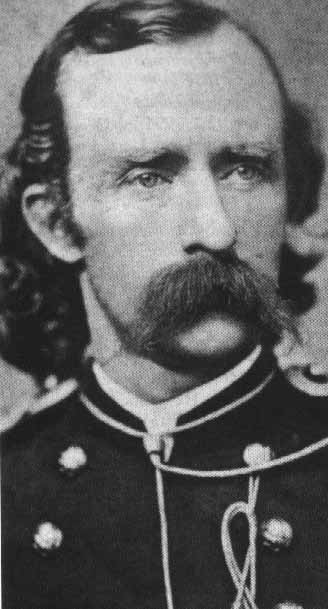

General George Armstrong Custer, Indian Fighter

b. December 5, 1839. d. June 25, 1876.

US Civil War General. One of the most famous and controversial figures in United States Military history. Graduated last in his West Point Class (June 1861). Spent first part of the Civil War as a courier and staff officer. Promoted from Captain to Brigadier General of Volunteers just prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, he helped defeat General Stuart's attempt to make a cavalry strike behind Union lines on the 3rd Day of the Battle (July 3, 1863). Participated in nearly every cavalry action from that point until the end of the war, always performing boldly, most often brilliantly, and always seeking publicity for himself and his actions. Ended the war as a Major General of Volunteers and a Brevet Major General in the Regular Army. Upon Army reorganization in 1886, he was appointed Lieutenant Colonel of the soon to be renown 7th US Cavalry. Fought in the various actions against the Western Indians, often with a singular brutality (exemplified by his wiping out of a Cheyenne village on the Washita in November 1868). His exploits on the Plains were romanticized by Eastern US newspapermen, and he was elevated to legendary status in his time. His military career culminated in the June 25, 1876 Battle of Little Big Horn and his "Last Stand", where he and most of his regiment were wiped out in one of the best known military actions of the 19th century. To this day General Custer's deeds and place in history spawn much debate and historical controversy.

The Boy General

Robert W. Marlin tells the story of George Armstrong Custer.

IN JULY 1861, the 20-year-old George Armstrong Custer graduated from the US Military Academy at West Point as a second lieutenant. He was the anchorman of his class: 34th in a class of 34. Less than a week after his arrival in Washington, he was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant, something that usually took a number of years to accomplish. Less than four years later at the age of 23, he held the rank of major general in the Union Army. He was one of the generals present when Lee surrendered to Grant at Appomattox. Less than 12 years later, he would ride to glory and into history on a Montana hillside. His family called him Autie, and his detractors referred to him as the Boy General.

Custers Rapid Rise

Second Lieutenant Custer left West Point on 18 July 1861. He reported to the War Department in Washington on 20 July. Within 72 hours he had his first taste of combat. He was assigned the duty of delivering dispatches to his new commanding officer. The very next day he took part in the first battle of Bull Run. Although the battle was a complete defeat for the Union forces, battlefield reports of it mentioned the outstanding leadership and bravery displayed by the shavetail (newly commissioned) Custer, who was promptly promoted to first lieutenant. In 1862 he was promoted to captain, in 1863 to brigadier general and in 1864 to major general.

Custers rapid rise must have been difficult for many seniors officers to accept. Career officers with 15 or 20 years service were placed in the position of taking orders from a boy young enough to be their son. The officer ranks were filled with militiamen and political appointees who had no practical military or leadership experience, but this did not stop them from having bruised egos. Most of these officers swallowed their pride and followed behind Custer. However, the career officers who were also West Point graduates felt differently. The officers knew that the brevet (temporary) ranks they held would be gone when the war was over. Still, many officers harbored a deep resentment toward Custer and never forgave him for usurping their own career opportunities.

Buffalo

Perhaps no animal in the history of any nation has ever played a more important role than the American buffalo has played in the life of America. The American buffalo is, of course, not a buffalo at all. It is a bison, which is related to the European wisent . The scientific world insists that the word "buffalo" should be used only to describe the African buffalo or the water buffalo of Asia. But for nearly 200 years Americans have called the bison a buffalo.

The American buffalo was the most important animal on the western plains and prairies. It even surpassed the mustang and the long-horn in importance. As a social factor the buffalo's influence on Indians and non-Indians alike was tremendous. In America the economic and social impact of the buffalo exceeded that of the beaver and the whale.

The first race of buffalo in North America came over from Asia about 200,000-800,000 years ago during the Illinoisan glacial age. These animals crossed on the landmass that once connected Asia to what is today Alaska. These first buffalo were stout animals compared to the buffalo that roamed the western plains of North America during the 1800s. They had very large horns that were thick and curved. Some fossil horns have a span of more than six feet, suggesting that these first buffalo were solitary in their habits and did not live in large herds.

For thousands of years the first buffalo spread slowly southward and eastward across North America. They ranged as far west as modern California, as far east as Florida, and perhaps as far south as present-day Central America. But gradually the cold Ice Age climate in which these animals lived began to change. About 120,000 years ago, toward the end of the last interglacial (Sangamon) period, the climate became warmer, and the first buffalo died out. In their place appeared two new forms. One of these, Bison antiquus , may have originated from the earlier buffalo; it was smaller than the first buffalo. It became extinct during the last glaciation (Wisconsin) period, about 9,000-11,000 years ago. The other new form, Bison occidentalis, did not die out. It prospered. From this species (B. bison), two groups of buffalo developed--the plains buffalo and the mountain or wood buffalo.

By the year 1000, these two species of buffalo could be found over a wide area of North America. The mountain or wood buffalo ranged from near the Great Slave Lake in present-day Canada southward through the Rocky Mountains into what is now New Mexico. It is possible that some of these animals also lived in the Appalachian Mountains, where they became known as Pennsylvania bison. But the largest number of buffalo were those on the plains and prairie lands of North America. There the animals prospered and multiplied to a far greater extent than those in the mountains and woodlands.

The first non-Indian known to have seen a buffalo was the Spanish explorer Hernn Corts. Cortees saw the animal in 1521 in a menagerie kept by Montezuma near where Mexico City stands today. Later, other Spanish explorers also saw buffalo. The earliest known sighting of buffalo in what is now the United States was in 1612, when Captain Samuel Argoll came upon the animal near where Washington, D.C., stands today.

Just how the word "buffalo" came into use is uncertain. To the Spanish explorers the animal was frequently called cibola . Some Spanish writers describe it as bisonte . Early French colonists usually called buffalo bison d'Amrique . Canadian voyageurs used the termboeuf meaning "ox" or "bullock." Later, French explorers called the animal thebufflo and later buffelo . It may have been from these terms, adopted by the English colonists, that the word "buffalo" originated.

East of the Mississippi River, the buffalo was slaughtered as European Americans moved over the Appalachians to make their homes. By the 1830s, all of the wild buffalo east of the Mississippi had been killed, but to the west, explorers, trappers, and traders found millions of buffalo on the plains and prairies. There the buffalo was an important commodity for the Indians, especially for about two dozen tribes on the western Plains and prairies. The animal's meat sustained life. Its tallow and grease were valuable. Its bones afforded material for implements and weapons. Its hide furnished blankets, garments, boats, ropes, and warm and portable houses. Its hooves produced glue, and its sinews were used for bowstrings and twine. Its skull was preserved as great medicine.

Indians on the Plains were not particularly wasteful in killing buffalo until after they obtained horses, which gave them more mobility. As contact with non-Indians grew, Indians began to kill buffalo to obtain robes and tongues, especially on the upper Missouri, to trade for European-American goods. By 1835, more buffalo robes than beaver pelts were being shipped down the Missouri River from Fort Union. Until 1871 only buffalo meat, tongues, and robes--the best robes were taken during the winter when buffalo had thick coats of hair--were valuable to the Americans.

In 1870, however, tanners found that they could make fine leather from buffalo hides regardless of the thickness of the robe. Hunters began killing buffalo. By 1872 more than half a million buffalo were slaughtered on the southern plains for their hides alone. The killing increased so rapidly that by 1880 nearly all the wild buffalo on the southern plains had been killed.

By then the slaughter of buffalo on the northern plains was under way. It had been delayed by the battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876 and the uprising by the Sioux Indians. By 1879, most of the wild buffalo in Wyoming and eastward through Nebraska had been killed, and by 1883 nearly all of the shaggies had been killed in Montana and Dakota Territory. What is believed to have been the last carload of buffalo robes and hides from the northern plains was shipped by rail from Dickinson in far western Dakota Territory in 1884.

In that year the largest single group of wild buffalo left in the United States were in Yellowstone National Park. But it was not until 1894 that Congress passed its first buffalo protection law. By then a handful of Americans were also trying to save the animal by capturing scattered live buffalo and raising them on ranches. These buffalo preservers included Texas rancher Charles Goodknight, Kansan C. J. "Buffalo" Jones, Dakota ranchers James "Scotty" Philip and Peter Depree, a Flathead Indian named Walking Coyote, and Montana ranchers Michel Pablo and Charles A. Allard. If it had not been for these and other men, the buffalo long ago would have gone the way of the passenger pigeon.

In 1913, the U.S. Treasury Department coined the buffalo nickel designed by James Earle Fraser who said that in his search for symbols, he had found "no motif within the boundaries of the United States so distinctive as the American buffalo." The U.S. Department of the Interior adopted the buffalo for its seal in 1929, and more than 200 place names in the United States have at one time or another contained the word "buffalo."

The American buffalo is preserved today in herds under the protection of many states and the federal government. As increasing number of private citizens also raise buffalo, many for profit. Animal breeders have crossed the American buffalo with domestic cattle to produce "beefaloes." Beefalo steaks are now sold commercially. The fate of the buffalo rests with the creature who nearly exterminated the animal and then paradoxically saved it--the human being.

This marker stands at the spot at Little Bighorn where Custer fell.

General Custer, as commander of the 3rd Cavalry Division, was very familiar to the members of the 15th. The "Red Neck Ties" were adopted by the regiment to honor there commander.

As the story goes word got back to the young general that the Confederates failed to see the dash, and daring reputation that the General was creating in the press. In fact, word was that the Confederates said they never saw the General in the field. Well, so that the rebels could not mistake him at the head of his command, the general fashioned a bright red neck tie to wear so that there would be no mistake about his presence on the field.

His Michigan troops, seeing this new fashion on the General's uniform, quickly adopted the same tie, so as the General would not be the target of a rebel marksman. To further honor the General, the 15th also adopted this, and became it's proud trademark.

George Armstrong Custer

1839-76, American army officer, b. New Rumley, Ohio, grad. West Point, 1861. Civil War Service

Custer fought in the Civil War at the first battle of Bull Run, distinguished himself as a member of General McClellan's staff in the Peninsular campaign, and was made a brigadier general of volunteers in June, 1863. The youngest general in the Union army, Custer ably led a cavalry brigade in the Gettysburg campaign. He fought in Virginia in the great cavalry battle at Yellow Tavern and in General Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley campaign. Made a divisional commander in Oct., 1864, he defeated (Oct. 9) Gen. Thomas L. Rosser at Woodstock. After dispersing the remnants of Gen. Jubal A. Early's command at Waynesboro on March 2, 1865, he was in the advance in pursuit of Lee's army beyond Richmond. Custer received the Confederate flag of truce, was present at the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, and was promoted major general of volunteers. His record (he had also been brevetted a major general in the regular army), considering his youth, was one of the most spectacular of the war. The 7th Cavalry

In the reorganization of the U.S. army after the war Custer was assigned to the 7th Cavalry with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and he remained the acting commander of this regiment until his death. In 1867 he was court-martialed and removed from command for leaving his command at Fort Wallace, Kansas, without permission, but in Sept., 1868, he was reinstated, mostly through the efforts of Sheridan, with whom he had always been a favorite. In the massacre of the Cheyenne and their allies at the battle of the Washita (Nov., 1868), he was accused of abandoning a small detachment of his men, who were annihilated. He served (1873) in Dakota Territory and in 1874 commanded the expedition into the Black Hills that led to renewed hostilities with the Sioux.

In the comprehensive campaign against the Sioux planned in 1876, Custer's regiment was detailed to the column under the commanding general, Alfred H. Terry, that marched from Bismarck to the Yellowstone River. At the mouth of the Rosebud, Terry sent Custer forward to locate the enemy while he marched on to join the column under Gen. John Gibbon. Custer came upon the warrior encampment on the Little Bighorn on June 25 and decided to attack at once. Not realizing the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Native Americans, most of whom lay concealed in ravines, he divided his regiment into three parts, sending two of them, under Major Marcus A. Reno and Capt. Frederick W. Benteen, to attack farther upstream, while he himself led the third (over 200 men) in a direct charge. Every one of them was killed in battle. Reno and Benteen were themselves kept on the defensive, and not until Terry's arrival was the extent of the tragedy known. The men (except Custer, whose remains were reinterred at West Point) were buried on the battlefield, now a national monument in Montana. Custer's spectacular death made him a popular but controversial hero, still the subject of much dispute as to his actions and character. Bibliography

Custer wrote My Life on the Plains (1874), and his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, 1842-1933, who devoted much of her life to upholding his memory, wrote Boots and Saddles (1885), Tenting on the Plains (1887), and Following the Guidon (1890). See also biographies by Frazier Hunt (1928) and Jay Monaghan (1959, repr. 1971); Charles A. Windolph, I Fought with Custer (as told to Frazier and Robert Hunt, 1947); W. A. Graham, The Story of the Little Big Horn: Custer's Last Fight (1959); E. I. Stewart, Custer's Luck (1955, repr. 1971); Evan S. Connell, Son of the Morningstar (1984). George Armstrong Custer 1839-76, American army officer, b. New Rumley, Ohio, grad. West Point, 1861. Civil War Service

Custer fought in the Civil War at the first battle of Bull Run, distinguished himself as a member of General McClellan's staff in the Peninsular campaign, and was made a brigadier general of volunteers in June, 1863. The youngest general in the Union army, Custer ably led a cavalry brigade in the Gettysburg campaign. He fought in Virginia in the great cavalry battle at Yellow Tavern and in General Sheridan's Shenandoah Valley campaign. Made a divisional commander in Oct., 1864, he defeated (Oct. 9) Gen. Thomas L. Rosser at Woodstock. After dispersing the remnants of Gen. Jubal A. Early's command at Waynesboro on March 2, 1865, he was in the advance in pursuit of Lee's army beyond Richmond. Custer received the Confederate flag of truce, was present at the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, and was promoted major general of volunteers. His record (he had also been brevetted a major general in the regular army), considering his youth, was one of the most spectacular of the war. The 7th Cavalry

In the reorganization of the U.S. army after the war Custer was assigned to the 7th Cavalry with the rank of lieutenant colonel, and he remained the acting commander of this regiment until his death. In 1867 he was court-martialed and removed from command for leaving his command at Fort Wallace, Kansas, without permission, but in Sept., 1868, he was reinstated, mostly through the efforts of Sheridan, with whom he had always been a favorite. In the massacre of the Cheyenne and their allies at the battle of the Washita (Nov., 1868), he was accused of abandoning a small detachment of his men, who were annihilated. He served (1873) in Dakota Territory and in 1874 commanded the expedition into the Black Hills that led to renewed hostilities with the Sioux.

In the comprehensive campaign against the Sioux planned in 1876, Custer's regiment was detailed to the column under the commanding general, Alfred H. Terry, that marched from Bismarck to the Yellowstone River. At the mouth of the Rosebud, Terry sent Custer forward to locate the enemy while he marched on to join the column under Gen. John Gibbon. Custer came upon the warrior encampment on the Little Bighorn on June 25 and decided to attack at once. Not realizing the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Native Americans, most of whom lay concealed in ravines, he divided his regiment into three parts, sending two of them, under Major Marcus A. Reno and Capt. Frederick W. Benteen, to attack farther upstream, while he himself led the third (over 200 men) in a direct charge. Every one of them was killed in battle. Reno and Benteen were themselves kept on the defensive, and not until Terry's arrival was the extent of the tragedy known. The men (except Custer, whose remains were reinterred at West Point) were buried on the battlefield, now a national monument in Montana. Custer's spectacular death made him a popular but controversial hero, still the subject of much dispute as to his actions and character. Bibliography

Custer wrote My Life on the Plains (1874), and his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, 1842-1933, who devoted much of her life to upholding his memory, wrote Boots and Saddles (1885), Tenting on the Plains (1887), and Following the Guidon (1890). See also biographies by Frazier Hunt (1928) and Jay Monaghan (1959, repr. 1971); Charles A. Windolph, I Fought with Custer (as told to Frazier and Robert Hunt, 1947); W. A. Graham, The Story of the Little Big Horn: Custer's Last Fight (1959); E. I. Stewart, Custer's Luck (1955, repr. 1971); Evan S. Connell, Son of the Morningstar (1984). Custer Web Links

The George A. Custer Homepage

The Court Martial of George Armstrong Custer

Custer, George Armstrong (1839-76). Soldier. Of Hessian ancestry, Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio. In 1857 he was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy by Congressman John W. Bingham. Never a good student, he distinguished himself by accumulating a number of demerits and graduating not only at the bottom of his class but under a disciplinary cloud. Custer, George Armstrong (1839-76). Soldier. Of Hessian ancestry, Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio. In 1857 he was appointed to the U.S. Military Academy by Congressman John W. Bingham. Never a good student, he distinguished himself by accumulating a number of demerits and graduating not only at the bottom of his class but under a disciplinary cloud.

Assigned to the 5th Cavalry in the Army of the Potomac, Custer soon attracted the attention of two generals, Phil Kearny and George McClellan, with his bold, reckless bravery and spectacular showmanship in several cavalry fights. Although Custer's 1863 promotion to brigadier general of volunteers was ascribed to politics and to the mistake of an overworked clerk, it was probably due to Custer's flair for the flamboyant and his success in whatever he undertook that was responsible. Several other similar promotions, all recommended by General Alfred Pleasanton, were made at the same time in what could be called a cavalry shake-up. Shortly afterward, Custer participated in the cavalry fight on the right flank at Gettysburg, which turned back Jeb Stuart's encircling movement and is said to have constituted "the margin of victory" that enabled the North to win this decisive battle of the Civil War.

Early in 1864 Custer married Elizabeth Bacon. After his return to duty, he participated in most of the remaining battles of the war in the East and played a decisive role in the preliminaries that brought about the surrender of General Lee at Appomattox. By the end of the Civil War, Custer was the youngest major general in the army.

When peace returned, Custer reverted to his regular army rank of captain. But when the army was enlarged in order to cope with the growing Indian menace on the Great Plains, he was appointed lieutenant colonel of the newly created 7th Cavalry. In 1867 the regiment played a prominent part in the Hancock Campaign, but because of a number of indiscretions--such as treating deserters cruelly and overmarching his troops--Custer was court-martialed, convicted, and suspended from rank and command for one year. Reinstated before his sentence expired, he led his regiment to victory at the Washita River, a battle that gave the 7th Cavalry its reputation but also sowed seeds of dissension within it, for some of the officers did not trust Custer's judgment (see Washita, Battle of the ).

After a brief tour of duty in the Department of the South, the regiment was transferred to Dakota in 1873 and, under Custer's command, constituted a part of the Stanley expedition, which explored the Yellowstone River in that year. In 1874 the expedition to the Black Hills, an area that was guaranteed to the Sioux by treaty, and Custer's claim that there was "gold at the roots of the grass" led to a stampede of miners into the area. This brought the troubles with the Sioux to a climax. In 1876 a full-scale campaign against the Sioux culminated in the battle of the Little Bighorn, where Custer and his command lost their lives.

The news of the disaster created an uproar among the American people and led to a controversy that has yet to be settled. Custer had a reputation for victory; for him, attack and victory were synonymous. He was known as the "American Murat," his regiment, as "the matchless Seventh." That the regiment had suffered defeat and its commander had died led some to suspect that treachery was involved--a suspicion fueled by the actions of certain other figures in the tragedy and by the somewhat contradictory reports from officials and dispatches from newspaper correspondents. The blame gradually came to settle on Major Marcus A. Reno, the second in command. At Major Reno's request, a court of inquiry into his responsibility was ordered in February 1879, but the testimony was so contradictory that it only added to the intensity of the controversy.

Elizabeth Bacon Custer also contributed her share to the confusion concerning her husband's career. In order to protect her husband's memory against his detractors, she wrote several books about him. The first, Boots and Saddles; or, Life in Dakota with General Custer (1885, repr. 1961), deals with the period just before the battle of the Little Big Horn. This was followed by Tenting on the Plains (1887, repr. 1969) and Following the Guidon (1890, repr. 1966).

The literature on Custer and the battle of the Little Big Horn is voluminous. Frederick Whittaker, A Complete Life of General George A. Custer (1876, repr. 1993), based on papers made available by Elizabeth Bacon Custer, is extremely pro-Custer, and this account has been generally followed by subsequent writers. In 1934 Frederic F. Van de Water published Glory-Hunter , which is anti-Custer. Mari Sandoz, Battle of the Little Big Horn (1966), stresses the theory that Custer had political ambitions and that his reckless attack on the Sioux can be attributed to his hopes for a spectacular victory, which would assure him the Democratic nomination for the presidency. See also Louise Barnett, Touched by Fire: The Life, Death, and Mythic Afterlife of George Armstrong Custer (1996); Paul Andrew Hutton, ed., The Custer Reader (1992); Jay Monaghan, Custer (1959); Richard Slotkin, The Fatal Environment (1985); Edgar I. Stewart, Custer's Luck (1955); Robert Utley, Cavalier in Buckskin: George Armstrong Custer and the Western Military Frontier (1988); and Jeffrey D. Wert, Custer: The Controversial Life of George Armstrong Custer (1996).--E. I. S.

PHOTO CREDIT: Yale Collection of Western Americana |

|

|

|

|

Native American Nations

Native American Nations