|

|

|

|

A CHRONOLOGY OF

AFRICAN AMERICAN MILITARY SERVICE

From the Civil War to World War I

The opening shots of the Civil War fired at Fort Sumter , South Carolina, on 12 April 1861 once again raised questions on both sides of the conflict about the feasibility and wisdom of using African Americans and Native Americans in a combat role. From the beginning of the armed clash, both sides used African Americans for a variety of essential but oftentimes menial support tasks. But neither side expected the war to last long enough to warrant the use of nonwhite combatants. What ultimately tipped the scales in favor of black participation was this first truly modern wars seemingly insatiable demand for manpower, along with President Abraham Lincolns decision to transform the conflict from a fight to preserve the Union into a crusade to abolish slavery.

Though initially denied the right to bear arms in the first year of the Civil War, by the end of 1862 black soldiers were fighting for the Union. Volunteer units from different states, along with the U.S. Colored Troops, went on to serve with distinction throughout the Civil War. Black soldiers won a total of 15 Congressional Medals of Honor , while another 7 African American sailors were also honored for their heroism. By January 1864, even Confederate officers began to appreciate the need for recruiting blacks for military service. The southern civilian leadership, however, opposed the idea until the final months of the war. By the time President Jefferson Davis signed a bill on 13 March 1865 authorizing the enlistment of slaves beginning 3 April, it was too late to save the Confederacy.

After General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House on 9 April 1865, many of the Unions all-black units began to muster out. Several other black units, however, remained on duty in the south during the Reconstruction period. The permanent presence of blacks in the peacetime military seemed assured by the formation of state militias allowing African Americans to serve, and the passage of federal legislation in 1866 that reorganized the armed forces and permitted blacks to enlist in the Regular Army. By 1869, the U.S. Army had four all-black units: the 9th and 10th Cavalry as well as the 24th and 25th Infantry regiments (the latter consolidated from four infantry regiments established earlier). In the more than half century from 1865 to 1916, members of these Regular Army units repeatedly proved their prowess in the Indian Wars of 1867-1891, the Spanish American War (1898), the Philippines Insurrection (1899-1901), and General John J. Pershings punitive expedition into Mexico in 1916. African American soldiers and sailors again won respect and recognition for their heroism by winning several Congressional Medals of Honor as well as laudatory comments from senior officers and the press.

Despite their loyalty, bravery, and ability to endure under adverse conditions, African American military men suffered many indignities because of racial discrimination. During the Civil War, blacks confronted inequalities in pay, length of enlistment, quality of weaponry and medical services, and promotional opportunities. By the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, "Jim Crow" discrimination and white contempt for blacks were increasingly reflected in the military environment. One of the worst insults given to African American servicemen involved unfounded white doubts about black servicemens fighting abilities and dedication to duty. As they had demonstrated time and again, when confronted with the enemy, black soldiers fought bravely because they were Americans, not because of their skin color or ethnic heritage.

The adverse conditions and discrimination that were part of the black military experience in the period between the Civil War and Americas entry into World War I in 1917 grew worse as the new century progressed. Black troops had to put up with substandard housing, equipment, and food. The difficulties experienced by African Americans who aspired to military command prohibited all but a handful of black officers from being commissioned. Numerous restrictions were placed on African American servicemen concerning assigned duties and promotional opportunities. As the nations armed forces modernized, blacks were excluded from the more technical areas. The official reason cited for these discriminatory practices was the lack of technical skill and general intelligence among black soldiers. Inevitably, such racist attitudes had a negative impact on the morale of the affected troops. Racially spawned clashes occurred more frequently between black soldiers and the communities surrounding the posts where African Americans were assigned, and at times escalated into serious riots, usually resulting in additional problems for the black troops. Racial tension in the armed forces and throughout the nation reached critical levels in the years preceding the outbreak of World War I.

But African Americans continued to join both the U.S. Army and Navy between 1898 and 1917, even though both services were beginning to cut back on the number of black recruits. In spite of the increasing racism, many black men still viewed the military as a place where they could prove their individual ability and worth in service to their country. They also hoped to win greater social participation for all blacks through their military sacrifice. Unfortunately these hopes were not realized for most African Americans in the early years of the 20th century where "Jim Crow" held sway. Yet when the call to arms came on 2 April 1917, African Americans again stood ready to give their lives for the freedom usually denied them.

New Orleans Native Guard

Contrabands, Camp Brightwood. Washington, D.C., ca. 1863

Harriet Tubman

Officers and Non-Commissioned Officers of the Second Battalion, Virginia Volunteers

Black soldiers in action at Island Mound

Jefferson Davis

Lewis Douglass

Buffalo Soldiers

William Carney

Ulysses S. Grant

Fort Pillow

Robert E. Lee

McClean House, Appomattox Court House, VA

9th Cavalry

Buffalo Soldiers

1861 Free blacks throughout the North petitioned President Abraham Lincoln for the right to bear arms, but their service was not accepted until later in the Civil War.

April 1861 The free blacks of New Orleans, Louisiana , began organizing a Native Guard battalion with officers of their own race. The state government approved this action and commissioned the black officers. The commanding general of the white and black troops sent a telegram to Confederate authorities in November 1861 because he was "elated at the success of being first to place negroes in the field together with white troops." Since their first duty was to defend New Orleans, the Native Guards refused to serve elsewhere for the Confederacy once Union forces captured the city. Many of the men later fought for the Union.

15 April 1861 President Abraham Lincoln declared a state of insurrection and called for 75,000 volunteers to serve for 3 months. At this time, the Union Army officially rejected black volunteers. Lincoln did not want to risk antagonizing the Border States or the Butternut Region; many northern whites did not think it appropriate for blacks to fight a "white mans war;" and most whites (including the president) did not think blacks would be good soldiers. However, the Secretary of the Navy authorized the enlistment of escaped slaves.

June 1861 The Tennessee legislature authorized the governor "to receive into the military service of the State all male free persons of color, between the age of 15 and 50, who should receive $8 per month, clothing and rations." If an insufficient number of blacks joined voluntarily, provisions were also included allowing officials "to press such persons until the requisite number is obtained."

6 August 1861 In an attempt to keep the Confederates from using slaves for military labor, the U.S. Congress passed legislation making it legal to confiscate any property (including slaves) used to aid the rebels.

September 1861 The Secretary of the Navy authorized the enlistment of blacks into the U.S. Navy . Although previously barred from service in the U.S. Army or Marine Corps, "Negroes were readily accepted all along the coast on board the war vessels, it being no departure from the regular and established practice in the service." By the end of the Civil War, traditional figures show that about 25 percent of Union sailors were African Americans, but more recent figures indicate that perhaps only 8 percent of the Navys total manpower was black.

1862 Harriet Tubman , probably the most well known "conductor" on the Underground Railroad , served as a nurse, cook, and laundress to Union troops in South Carolina. She also supported the Union cause as a spy, scout, and guerilla leader. In June 1863, she led Union troops in a raid along the Combahee River. Described as "the only American woman to lead troops, black or white, on the field of battle," she and men under the command of Colonel James Montgomery freed 750 to 800 slaves, confiscated property worth thousands of dollars, and destroyed several million dollars of commissary stores and cotton.

May 1862 Major General David C. Hunter pioneered the recruiting of blacks by organizing the 1st South Carolina Volunteer Infantry at Beaufort. The War Department disrupted this effort until the end of August 1862. Although not officially called to active duty until 31 January 1863, Company A of Hunters 1st South Carolina was unofficially the very first unit of former slaves permitted to join the Union Army. It was redesignated the 33rd Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops (USCT) in February 1864. It mustered out in January 1866.

June 1862 Flamboyant Kansas Senator James H. Lane began recruiting troops from the growing number of black fugitives who escaped or were liberated from their masters in Missouri and Arkansas. Known as the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry, unit members wore red silk pantaloons and wool jackets. By late August there were 500 ex-slaves camped outside Leavenworth, trained and ready to do battle. The unit would later become known as the 79th Infantry Regiment, USCT.

July 1862 The U.S. Congress passed the Militia Act, which authorized the president to use black troops in combat. Lincoln, however, continued to use black manpower primarily in a support role as laborers, kitchen workers, nurses, scouts or spies. Although the figures vary, at least 186,000 African Americans eventually served in the Union Army, while another 30,000 blacks enlisted in the Navy. Several thousand others also supported the war effort as laborers. At least 68,000 blacks were killed or wounded during the Civil War.

25 August 1862 After the disastrous Peninsular Campaign, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton ordered Brigadier General Rufus Saxton to organize 5000 black troops who were to receive equal pay and rations with whites.

September 1862 General Benjamin F. Butler in the Department of the Gulf began recruiting blacks for service in the segregated Louisiana Native Guard regiments. The line officers of the 1st and 2nd Regiments were black, while the field officers were white. The 3rd Regiment was "officered regardless of color." Composed of free men and former slaves, beginning on 27 September 1862, these three units became the first all-black regiments officially mustered into Union Army ranks.

27-28 October 1862 The first use of black troops in combat during the Civil War involved a 225-man detachment from the 1st Kansas Colored Volunteer Infantry, who fought in a 2-day engagement at Island Mound, Missouri. A total of 10 men were killed and 12 were wounded. Contemporary accounts of the battle praised the black soldiers martial skills and bravery.

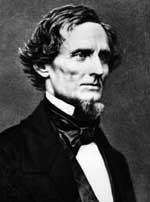

23 December 1862 Confederate President Jefferson Davis "raised the black flag" against the North by signing a proclamation ordering the execution of any white Union officers of black troops. In addition, "all negro slaves captured in arms" were to be turned over to the authorities "of the respective States to which they belong, anddealt with according to the laws of said States." This decision was subsequently endorsed in May 1863 by a resolution passed by the Confederate Congress. After the massacre at Fort Pillow in April 1864 (see separate entry), President Lincoln responded by announcing an equal exchange of executions and hard labor sentences for Confederate officers and enlisted men being held prisoner by the Union.

1863 Secretary of War Stanton ordered that black volunteers be paid at a lower rate than white volunteers, because blacks were considered to be auxiliaries. Instead of the $13 per month paid white troops, regardless if they were volunteers or regular army, African Americans were paid $10, less a $3 deduction for clothing. Many black regiments refused to accept the lesser amount. In addition to less pay initially, African Americans also faced other forms of discrimination: longer enlistment periods, little chance for promotion, inadequate medical care, inferior weapons, and usually no prisoner-of-war status.

1863 The 9th Regiment USCT composed the first known battle hymn by black soldiers, "They Look Like Men of War."

1 January 1863 Lincolns Emancipation Proclamation , a preliminary version of which was first announced to the public in September 1862, went into effect on this date. Provisions for the use of black troops were included in the document. The preliminary statement had opened the armed forces to Confederate slaves who were able to escape and make their way to Union lines.

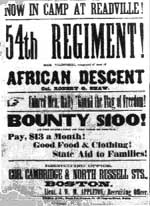

9 February 1863 In response to Lincolns proclamation and with the federal governments permission, Governor John A. Andrew of Massachusetts ordered the organization of the all-black 54th Massachusetts Regiment . On 21 February 1863, the first 25 volunteers were organized at Camp Meigs, Readville, Massachusetts. Because of problems enlisting enough black volunteers only from New England, the recruitment area was expanded to encompass the entire Union and its territories. Help from black and white abolitionists, most notably Frederick Douglass , also helped Massachusetts attract the necessary numbers of African Americans. After being involved in a number of significant campaigns during the war, members of the regiment mustered out in August 1865.

3 March 1863 Congress passed the first national Conscription Act, requiring the enlistment of males between 20 and 45. Substitutes or a payment of $300 could be used for exemption. Although the new law did not exclude African Americans, resentment against the act erupted into violence against blacks who were accused of starting the Civil War. During the four days from 13 to 16 July 1863, primarily Irish-Americans and other poorer men hit hard by the new act, participated in draft riots in New York City, destroying property and lynching blacks. Federal troops were called in to restore order.

14 March 1863 During the Battle of Port Hudson (the last Confederate fort on the lower Mississippi River), five all-black Louisiana regiments sustained severe losses in the unsuccessful Union assault on the fortification. Although a Union defeat, the black troops received considerable praise for their gallantry and determination under fire.

May 1863 The 55th Massachusetts Regiment was organized.

May 1863 Pennsylvania established Camp William Penn to train black enlistees.

1 May 1863 Major General Nathaniel P. Banks issued General Orders No. 40, organizing the Corps dAfrique in Louisiana. It was originally planned that the Corps would consist of 18 regiments representing infantry, artillery, and cavalry.

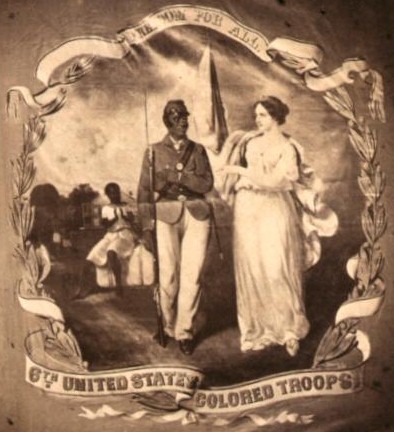

22 May 1863 General Order No. 143 established the Bureau of Colored Troops. Between 178,000 and 200,000 ex-slaves, free blacks, and white officers served under this organization.

28 May 1863 The 54th Massachusetts embarked for South Carolina.

6 June 1863 General Order No. 47 redesignated the 1st to 4th Regiments of the Louisiana Native Guards as the 1st to 4th Regiments of Infantry of the Corps dAfrique. Black officers of the first three regiments were displaced by whites.

28 June 1863 Black troops with the small Union garrison at Millikens Bend (near Vicksburg, Mississippi) again proved their military mettle in ferocious hand-to-hand combat until the attacking Confederate force was driven off by the Union warship Choctaw .

July 1863 General Quincy A. Gillmore ordered that no distinction be made among troops in his command.

18 July 1863 Probably the best known of the all-black regiments mustered during the Civil War, the 54th Massachusetts earned widespread fame for its unsurpassed bravery during the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina. The units white commanding officer, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw , and 116 enlisted men died in the unsuccessful attempt to take the Confederate fort. Another 156 members of the 54th were wounded or captured during this battle. Union forces finally occupied Fort Wagner on 6 September 1863, after it had been evacuated by the Confederates.

18 July 1863 Sergeant William H. Carneys bravery under fire during the assault on Fort Wagner earned him the Congressional Medal of Honor . He was the first African American to receive this prestigious award. Another 14 black soldiers were also honored with this medal for their heroism during the Civil War.

August 1863 Iowa authorities began enlisting blacks as part of the states quota. On 11 Oct, nine full companies, designated the 1st African Descent Regiment Iowa Volunteers, were mustered into the Union Army.

24 August 1863 In a letter to the Adjutant General, General Ulysses S. Grant noted that, "The Negro troops are easier to preserve discipline among than are our white troops, and I doubt not will prove equally good for garrison duty. All that have been tried have fought bravely." These sentiments echoed those expressed the day before in a letter to President Lincoln where Grant stated, "By arming the Negro we have added a powerful ally. They will make good soldiers."

29 August 1863 Because of a lack of black enthusiasm for enlisting after General Banks changes creating the Corps dAfrique, the Army issued General Order 64. It assigned responsibility to the Provost Marshal General for conscripting "all able-bodied men of color" into the Corps dAfrique. Strict guidelines governing the behavior of Corps soldiers were also established.

17 September 1863 General Quincy A. Gillmore issued General Order No. 77 prohibiting the use of black troops "to prepare camps and perform menial duty for white troops."

2 January 1864 Officers in the Confederate Army of Tennessee proposed recruiting blacks for military service in exchange for freedom. Confederate leaders rejected the suggestion at this time.

8 January 1864 Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts introduced a bill to encourage army enlistments. A measure to redress the pay inequity between black and white volunteers was also included.

11 March 1864 Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew commissioned First Sergeant Stephen A. Swails as Second Lieutenant, Company F, 54th Massachusetts. Andrew subsequently promoted two more black sergeants to second lieutenants, and within 3 weeks both men were promoted to first lieutenant. Another eight sergeants in the 55th Massachusetts were also commissioned as second lieutenants, but only three actually mustered in as officers.

April 1864 The 1st Regiment Corps dAfrique was renamed the 7th Regiment USCT. It was redesignated the 10th Regiment USCT the following month. In October 1865, the 77th Regiment Infantry was consolidated with the 10th. In addition, all of the other Corps dAfrique units were eventually redesignated as USCT regiments.

13 April 1864 After the Union surrender at Fort Pillow, Kentucky, troops under the command of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest massacred about 300 unarmed white and black soldiers.

18 April 1864 Union Major General Frederick Steele, during a diversionary campaign south of Little Rock, Arkansas, sent a party of 1000 troops on a foraging expedition. Among Steeles troops was the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry. While returning from their successful quest for supplies, the detachment encountered a significantly larger Confederate force at Poison Spring. After intense fighting, the Confederates prevailed. The 1st Kansas sustained very heavy losses in this skirmish117 killed out of 182 men who fought (64 percent). Many of the fatalities were the result of intense racial hatred. The Confederates and their Choctaw allies killed the African American soldiers as they attempted to surrender or as they laid wounded on the battlefield.

15 June 1864 After months of debate, Congress passed a law giving African Americans equal pay, arms, equipment, and medical services. This same legislation also freed the enslaved wives and children of black soldiers serving with Union forces.

19 June 1864 Joachim Pease won the Congressional Medal of Honor. A black seaman who was the loader of the number one gun, Pease served on the USS Kearsarge , which sank the Confederate raider Alabama off the coast of France on this date. He was one of seven black sailors to be so honored for their heroism during the Civil War.

1 August 1864 The War Department ruled that black troops would be given full pay retroactive to 1 January 1864, provided they were free men on 19 April 1861.

5 August 1864 During the Battle of Mobile Bay, John Lawson , a black landsman on the USS Hartford , emerged as a hero when he continued to man his duty station despite serious injury. His action kept Union guns operative. He was later awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor.

September 1864 General William T. Sherman wrote to Washington authorities to protest the organization of black troops in his department. Years later, however, he wrote to Secretary of War James D. Cameron, advising him to remove the word "black" from military regulations and urging him to integrate the armed forces.

November-December 1864 Despite his earlier letter, black troops actively participated in Shermans March to the Sea. They served as members of the raiding parties and expeditions sent out to intercept and disrupt Confederate communications as well as to destroy railroads and military stores.

December 1864 The 1st Regiment Kansas Volunteers was redesignated the 79th Regiment USCT.

1865 President Lincoln made Martin R. Delany a major, the first African American to be commissioned at this rank in the U.S. Army. He also approved Delanys plan for placing a black regiment in the field, but the Civil War ended before it could be implemented. Delany was also a well known advocate for the establishment of a black nation in the American west or in Africa.

1865 Lincoln proposed giving the vote to blacks who were either Civil War veterans or educated. Although not enacted at this time, the right of African American males to vote was eventually embodied in the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was ratified on 3 February 1870.

18 February 1865 General Robert E. Lee again agreed with plans to arm free blacks and ex-slaves to fight for the Confederacy. In a letter on this date, he wrote, "with reference to the employment of negroes as soldiers[,] I think the measure not only expedient but necessary. [I]n my opinion, under proper circumstances the negroes will make efficient soldiers." In an earlier letter of 11 January 1865, Lee recommended a special inducement to convince slaves to fight. "Such an interest we can give our negroes by granting immediate freedom to all who enlist, and freedom at the end of the war to the families of those who discharge their duties faithfully, whether they survive or not."

3 March 1865 Since most African Americans serving with Union forces were not free men before 19 April 1861, many units used mild subterfuge to guarantee them full pay. Consequently, protests about the inequity of the earlier legislation continued to surface. On this date, however, Congress finally put the issue to rest when it authorized equal pay for all black soldiers retroactive to their actual dates of enlistment.

13 March 1865 Confederate President Jefferson Davis signed legislation authorizing the enlistment of up to 300,000 slaves, who would be emancipated if they honorably discharged their duties.

3 April 1865 The day appointed to begin the drafting of slaves for military service came too late to save the Confederacy. The war ended in a Union victory less than a week later.

9 April 1865 Black troops were among the Union forces at Appomattox Court House when General Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia. African American soldiers had fought in all of the significant campaigns in the Petersburg-Richmond area that helped to bring the Civil War to a close.

11-14 May 1865 The last battle of the Civil War was fought in Texas near the Rio Grande. African American troops from the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry Regiment and white soldiers from the 2nd Texas Cavalry Regiment and the 34th Indiana Volunteer Infantry participated in the fighting which took place between Whites Ranch and Palmeto Ranch.

1866 Soon after the Regular Army established its black regiments, 22 states and the District of Columbia organized similar National Guard units. Reconstruction governments in the South recruited large numbers of African Americans to help maintain order and ensure Republican control, but black communities throughout the North and Midwest took the lead in getting the new units organized in those areas. One major difference between the state and federal units was the commissioning of African Americans as company and field grade officers in the National Guard.

1-3 May 1866 During 3 days of racial violence in Memphis, Tennessee, white civilians and police killed 46 African Americans and injured numerous others. At least two whites were also killed. In addition, mobs burned 90 houses, 12 schools, and 4 churches. The establishment of Fort Pickering, a post for black troops, and the use of black soldiers to patrol the city contributed to the tension that erupted into one of the bloodiest riots of the Reconstruction Era. It was only one of several violent outbreaks in the South that helped Radical Republicans win support for their own plan of Military Reconstruction.

28 July 1866 Radical Republicans in Congress pushed through legislation allowing blacks to serve in the armed forces during peacetime. In the resulting reorganization, the U.S. Army established 67 regiments, 6 of which were all black. There were two cavalry (the 9th and 10th) and four infantry (the 38th, 39th, 40th and 41st) units, each containing about 1000 men. Blacks were excluded from the five artillery units, because white leaders believed African Americans did not have the required technical skills. Most of the blacks who enlisted in the reorganized U.S. Army were Civil War veterans.

1869 The Army reorganized its black infantry units, combining the original four regiments into twothe 24th and 25th Infantry. They, along with the 9th and 10th Cavalry, saw action in the ongoing Indian wars that troubled the West between 1865 and 1898. During this period of service, the Native Americans began referring to the black troopers as "buffalo soldiers." This nickname was derived partly from the soldiers physical characteristics (i.e., dark skin and tightly curled hair) which were reminiscent of the buffalo, and partly from the Indian warriors respect for the black troopers fighting abilities.

1869 Robert Brown Elliot served as adjutant general of South Carolina, with responsibility for establishing a state militia to protect black and white citizens from the Ku Klux Klan . The following year, he became the first black general to command the South Carolina National Guard.

Part I - Part II - Part III - Part IV

|

|

|

|

|

|

Military Chronology

Military Chronology