A CHRONOLOGY OF

AFRICAN AMERICAN MILITARY SERVICE

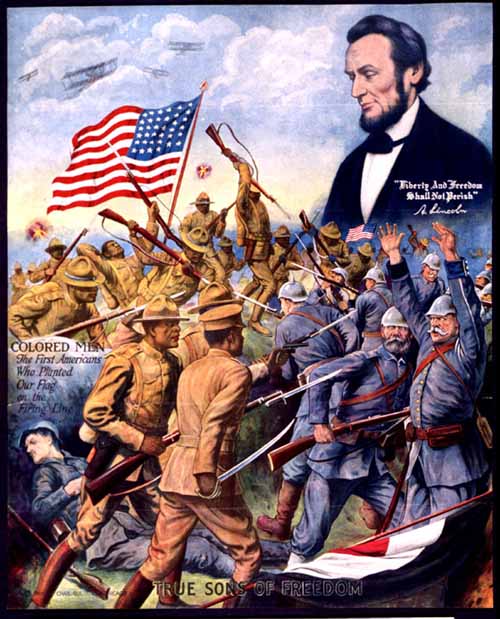

From WWI through WWII Part I

|

During the global conflicts of the first half of the 20th century, U.S. servicemen fought in Europe for the first time in the nations history. African Americans were among the troops committed to combat in World War I (WWI) and World War II (WWII), even though they and other black Americans were denied the full blessings of the freedom for which the United States had pledged to fight. Traditional racist views about the use of black troops in combat initially excluded African Americans from the early recruiting efforts and much of the actual combat in both wars. Nonetheless, large numbers of African Americans still volunteered to fight for their country in 1917-18 and 1940-45. Once again, many black servicemen hoped their military contribution and sacrifice would prove to their white countrymen that African Americans desired and deserved a fully participatory role in U.S. society. Unfortunately, the deeply entrenched negative racial attitudes prevalent among much of the white American population, including many of the nations top military and civilian leaders, made it very difficult for blacks to serve in the military establishment of this period. African American servicemen suffered numerous indignities and received little respect from white troops and civilians alike. The historic contributions by blacks to the defense of the United States were usually ignored or downplayed, while combat failures similar to those of whites and violent racial incidents often provoked by whites were exaggerated into a condemnation of all African Americans. In the "Jim Crow" world of pre-1945 America, black servicemen confronted not only the hostility of enemies abroad but that of enemies at home. African American soldiers and sailors had two formidable obstacles to deal with: discrimination and segregation. Yet, black servicemen in both world wars repeatedly demonstrated their bravery, loyalty, and ability in combat or in support of frontline troops. Oftentimes, they accomplished these tasks without proper training or adequate equipment. Poor communications and a lack of rapport with their white officers were two additional burdens hampering the effectiveness and efficiency of African Americans in the military. Too frequently, there was little or no recognition or gratitude for their accomplishments. One of the worst slights of both wars was the willingness of the white establishment to allow racism to influence the award of the prestigious Medal of Honor. Although several exceptionally heroic African Americans performed deeds worthy of this honor, not one received at the time the award that their bravery and self-sacrifice deserved. It took over 70 years for the United States to rectify this error for WWI and over 50 years for WWII. Despite the hardships and second-class status, their participation in both wars helped to transform many African American veterans as well as helped to eventually change the United States. Though still limited by discrimination and segregation at home, their sojourn in Europe during WWI and WWII made many black servicemen aware that the racial attitudes so common among white Americans did not prevail everywhere else. The knowledge that skin color did not preclude dignity and respect made many black veterans unwilling to submit quietly to continuing racial discrimination once they returned to the United States. In addition, the growing importance of black votes beginning in the 1930s and 1940s forced the nations political and military leaders to pay more attention to African Americans demands, particularly in regard to the military. Although it was a tedious and frustrating process, one too often marked by cosmetic changes rather than real reform, by the end of World War II, the U.S. military establishment slowly began to make some headway against racial discrimination and segregation within its ranks. The stage was set for President Harry S Trumans landmark executive order of 26 July 1948. |

|

|

October

1916

After joining the French Foreign Legion before the war, then serving

with the French infantry in 1915, African American Eugene Jacques

Bullard transferred into the French Air Service, where he became a

highly decorated combat pilot. Known as the "Black Swallow of

Death," Bullard flew over 20 combat missions. Despite his

outstanding record, Bullard was never allowed to fly for the United

States, even after it entered the war.

1916-17 Because of the growing bias against the use of black soldiers, African Americans serving in the regular Army and National Guard numbered about 20,000 (approximately 2 percent of all service-men). There were only three black commissioned officers. Despite the Armys need for men when war was declared, it initially continued to reject most African American volunteers. 1917 Dr. Louis T. Wright, the first black physician appointed to the staff of a white hospital in New York City (1919), served during WWI as a first lieutenant in the Medical Corps. He introduced the injection method of smallpox vaccination eventually adopted by the U.S. Army. 1917 Lloyd A. Hall was appointed Assistant Chief Inspector of Powder and Explosives in the U.S. Ordnance Department. He held the position for 2 years. 1917 Noted architect Vertner W. Tandy was the first black officer in the New York National Guard. Commissioned as a first lieutenant, he was later promoted to captain, then major. 1917 Alton Augustus Adams became the first black bandleader in the U.S. Navy. 1917 The Army forced its highest-ranking African American officer to retire, supposedly because he was unfit for duty. Although Colonel Charles R. Young suffered from high blood pressure and Brights disease, white leaders rejection of black proposals that Young command an all-black division may actually have been the motive behind the Armys decision. Determined to continue his Army career, Young rode his horse from Ohio to Washington, D.C., to demonstrate his fitness for duty. However, he was not reinstated until November 1918, at which time the Army assigned him to Fort Grant, Illinois, where he trained black troops. 1917 The American Red Cross rejected the applications of qualified African American nurses on the grounds that the U.S. Army did not accept black women. 25 March 1917 The District of Columbia National Guard, under command of African American officer Major James E. Walker, was assigned to protect the national capital. 6 April 1917 The United States entered World War I after President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. The Senate concurred on 4 April 1917, while the House agreed on 6 April. Over 367,000 African American soldiers served in this conflict, 1400 of whom were commissioned officers. Most blacks were placed in noncombat Services of Supply (SOS) units (i.e., labor battalions); for example, 33 percent of the stevedore force in Europe was black. At least 100,000 African Americans were sent to France during WWI. Despite the American restriction on the use of blacks in combat units, about 40,000 African Americans fought in the war. 18 May 1917 Congress passed the Selective Service Act authorizing the registration and draft of all men between 21 and 30, including African Americans. About 700,000 black men volunteered for the draft on the first day, while over 2 million ultimately registered. Previously, in April 1917, the American Negro Loyal Legion advised the federal government that it could quickly raise about 10,000 African American volunteers. Shortly after the draft was instituted, the Central Committee of Negro College Men organized at Howard University furnished over 1500 names in response to an Army requirement for 200 college-educated blacks to be trained at a promised officers school. Despite African American support for the war effort, some Army leaders had doubts about enlisting large numbers of blacks because senior officers either feared the negative response of southern politicians, believed blacks could not fight, or were concerned about possible subversion by an "oppressed minority." Because of the large number of blacks seeking to enlist, the War Department ordered that African Americans not be recruited. 19 May 1917 After Congress authorized 14 training camps for white officer candidates but none for African Americans, black protests and pressure on Army officials and Congress forced the War Department to correct this discriminatory situation. On this date, the U.S. Army established the first all-black officer training school at Fort Des Moines, Iowa. About half of the black officers during the WWI were commissioned in the first 4 months after classes began on 15 June 1917. Of these officer candidates, 250 were drawn from the noncommissioned officers (NCOs) of the four black Regular Army units. 21 May 1917 Leo Pinckney was the first African American drafted in WWI. June 1917 The first American troop ship dispatched to France included over 400 black stevedores and longshoremen. By November 1918, about 50,000 African Americans in the U.S. Army were employed as laborers in French ports. The SOS units handled a variety of duties: loading and unloading cargo, constructing roads and camps, transporting materials, laying railroad tracks, digging graves and ditches, serving as motorcycle couriers and military train porters, etc. Their physical accomplishments often impressed the French. In September 1918, for example, black servicemen unloaded 25,000 tons of cargo per day for several weeks, well over the amount French officials estimated could be moved in one month. 23 August 1917 Increasing racial tension involving U.S. servicemen eventually flared into a major riot in Texas where black troops were assigned to Camp Logan to guard the construction of a training facility. Members of the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 24th Infantry Regiment stationed in the Houston area had been provoked by weeks of racial harassment culminating in an attack on, then arrest of Corporal Charles W. Baltimore. These racial problems were compounded by the absence of the stabilizing influence of experienced black NCOs and the presence of inexperienced and insensitive white officers. At least 100 unit members responded to the tense, rumor-charged situation by marching on the town, where they opened fire on the police station, killing 16 whites (including 5 policemen) and wounding 12 others. In the next 14 months, the Army quickly court martialed 6 men from the 1st Battalion and 149 from the 3rd in four separate trials. Army investigators identified individual soldiers involved and brought charges against each one separately. During the trial of the first 64 men charged, 5 were freed, 4 were convicted of lesser charges, 42 were given life sentences, and 13 were condemned to die. Another 16 men were condemned to hang in two later trials. September 1917 Emmett J. Scott was appointed Special Assistant to the U.S. Secretary of War. A former secretary to Booker T. Washington, Scott worked to assure the nondiscriminatory application of the Selective Service Act. 17 October 1917 The Army commissioned 639 black officers who had been trained at the new all-black facility established at Fort Des Moines. By wars end, the school had produced 1400 commissioned officers, many of whom commanded labor battalions. Others, however, served in combat with distinction. 11 December 1917 The Army carried out the executions of the first 13 men (one of whom was Corporal Charles W. Baltimore) condemned to die for their role in the Houston riot. To lessen public reaction, there was no prior public announcement of the executions, nor did the Army allow any appeals. Because of black Americans very negative response to these actions, President Woodrow Wilson was forced to modify existing War Department policy. From then on, the president would examine the death penalty verdicts in all military law cases. Of the 16 men condemned in two subsequent trials, 10 had their sentences commuted, while the death sentences were upheld for 6 soldiers found guilty of killing specific individuals. 27 December 1917 The 369th Infantry Regiment (or "Harlem Hellfighters") was the first all-black U.S. combat unit to be shipped overseas during WWI. Unfortunately, this distinction was the result of a violent racial incident in Spartanburg, South Carolina. The units unquenchable desire to win justice and avenge a physical attack on their drum major, Noble Sissle, ultimately forced the War Department to send them to Europe. Because there was no official combat role at this time for Americas black soldiers, General John J. Pershing responded to Frances request for troops by assigning the 369th (and the 93rd Divisions other regiments) to the French army. The Germans dubbed the unit the "Hellfighters," because in 191 days of duty at the front they never had any men captured nor ground taken. Almost one-third of the unit died in combat. The French government awarded the entire regiment the Croix de Guerre. Sergeant Henry Johnson was the first African American to win this prestigious award when he singlehandedly saved Private Needham Roberts and fought off a German raiding party. 1917-18 African American women supported the WWI effort by organizing and serving as hostesses at YMCA centers for black soldiers ready to embark for France. They also served as nurses with the integrated Field Medical Supply Depot in Washington, D.C. 1917-18 After the racial clashes in Texas and other parts of the United States, Army leaders became increasingly distrustful of the Armys longstanding black units. The 24th and 25th Infantry Regiments never went to France. Instead the 24th Infantry spent the entire conflict guarding far-flung outposts on the Mexican border, while the 25th Infantry was sent to the Philippines and Hawaii. The Army also abandoned its plans to raise 16 regiments to accommodate the numerous black draftees, because it feared the likelihood of other violent racial incidents. It eventually activated the all-black 92nd and 93rd Infantry Divisions, both of which suffered during the war from incomplete training, the prejudice of white officers, inadequately prepared replacements, and the lack of Army enthusiasm and support. Compounding these handicaps was the fact that all too often during combat in World War I black troops were also blamed unfairly for problems caused by inadequate white leadership as well as ineffectual combat planning and coordination. 1917-18 Although it was never formally organized as a division (it had only four infantry regiments and no service or support units), the 93rd Infantry Division actually achieved a better combat record than the 92nd Infantry Division. Much of the divisions success in battle was the result of unit cohesiveness among the former National Guard unit members who made up the bulk of the 93rd Divisions troops. Another important factor was the assignment of the division to the French, who trained, equipped, and fielded these men without regard to race. Strangely enough, white U.S. Army officers thought they were disparaging the combat effectiveness of the 93rd by attributing it to the integration of the French forces. It took the U.S. military three more decades and two more overseas wars to realize the inefficiency of its shortsighted and discriminatory policy of racial segregation. 1918 The 369th Infantrys regimental band, conducted by noted black musician and composer James Reese Europe, was credited with introducing American jazz to France and the rest of Europe. The band traveled throughout France in the early months of this year, giving concerts that featured this uniquely African American music. Black musicians in other regiments also helped to spread an appreciation for jazz to Europes civilian population. 1918 Ralph Waldo Tyler, a reporter and government official, was the first and only official African American war correspondent in WWI. The Committee on Public Information accredited Tyler to report on war news of interest to black Americans. 1918 A racial incident in Manhattansville, Kansas, was sparked by a local theaters refusal to admit a black sergeant, a type of discrimination prohibited by state law. The theater owner was fined after other African American soldiers and the black press openly protested the event. To avoid similar problems in the future, however, the local Army commander ordered black servicemen "to refrain from behavior that would provoke a racial response." June 1918 The all-black 92nd ("Buffalo") Division, which had been activated in October 1917, arrived in France, then moved to the front in August 1918. Formed entirely of African American draftees, many of the divisions men (mainly those from the 365th and 366th regiments) were assigned to road-building details. However, members of the 367th and 368th regiments remained under fire almost constantly until the armistice of November 1918. Despite individual acts of heroism, Army leaders maintained that the division did not perform well under combat conditions. Much of their criticism was based on the 368th Infantry Regiments inability to withstand the German assault in the Argonne forest in September 1918, although white units in the area suffered the same failure. After its transfer to another command, the 92nd Divisions performance improved with better training and increased morale. For its combat success and bravery at Metz in November 1918, the French awarded the Croix de Guerre to the 1st Battalion, 367th Infantry Regiment. Unfortunately, the divisions accomplishments could not overcome the racism of its white leadership. The latters poor opinion of the unit, which they attributed to undesirable racial characteristics, had a significant impact on the U.S. armed forces subsequent policies on the use of African American servicemen. The unit was disbanded after WWI, but was reactivated in October 1942 for duty during WWII. July 1918 In an editorial written for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) publication, Crisis, W.E.B. DuBois urged black Americans to put the war effort before their own needs by "closing ranks" with white Americans in support of the fighting in France. His sentiments were partly based on the continuing belief that African American military participation might help win greater acceptance and freedom for all blacks in the United States. They were also partly based on DuBois own desire to win a commission with Army intelligence, which he later declined. August 1918 Senior U.S. Army officers had the 369th Infantrys musicians ordered back from the front to support troop morale by entertaining Allied soldiers in camps and hospitals. 7 August 1918 At the urging of U.S. Army officers, the French liaison to the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) Headquarters issued a "secret" memorandum instructing his fellow officers and civilian authorities on how to "handle" African American troops during WWI. To avoid any unpleasantness with the Americans, he advised other French officers to keep their distance from any black officers, to give only moderate praise to black troops, and to keep black troops and white French women apart. September 1918 The all-black 809th Pioneer Infantry arrived in France. During the 14-day voyage aboard the troop ship President Grant, about half of the 5000 men on board fell ill with "Spanish flu" (a global influenza epidemic that killed millions of people in 1918-19). So many men died en route that their bodies had to be buried at sea. The first task allotted 75 of the units men upon the ships arrival in France was that of unloading the bodies of additional flu victims. Called "Black Yankees" by the French (an ironic nickname since many of the 809ths men were from the South), this pioneer infantry unit (i.e., a construction crew) built hospitals and completed extensive repairs and new construction at the French port of St. Nazaire, where many American soldiers disembarked in WWI. Although trained to fight, the 809th worked mainly in construction until the Armistice. 3 September 1918 German propaganda leaflets dropped on African American troops attempted to exploit the contradictory attitudes reflected in American society. The Germans touched on a sensitive area by noting that black troops were sent to fight for democracy in Europe, while being denied this same personal freedom at home. The leaflets unsuccessfully urged black soldiers to defect. "To carry a gun in this service is not an honor but a shame. Throw it away and come over to the German lines. You will find friends who will help you." 16 September 1918 The U.S. Army executed the last six soldiers sentenced to die for their involvement in the Houston riot. For the next two decades, the NAACP campaigned to win the release of the remaining imprisoned rioters. This effort eventually resulted in the freeing by 1938 of the last men involved in the deadly incident. November 1918 The 369th (or "Harlem Hellfighters") was the first Allied regiment to reach the Rhine River during the final offensive against Germany. November 1918 Members of the 370th Infantry Regiment won 21 American Distinguished Service Crosses and 68 French Croix de Guerre during WWI. This all-black unit from Illinois fought in the last battle of WWI and captured a German train a few minutes after the Armistice was declared. 13 November 1918 The Army Nurses Corps accepted 18 black nurses on an "experimental" basis following the influenza epidemic. The Army sent half of them to Camp Grant, Illinois, and the other half to Camp Sherman, Ohio. Although their living quarters were segregated, they were assigned to duties in an integrated hospital. Because of the postwar reduction in force, the Army released all 18 women in August 1919. 1919 Despite the valor and efficiency with which most black Americans discharged their duty to the United States during World War I, they received little recognition for their efforts once they returned home. Although the 369th Infantry Regiment was honored with white soldiers in a grand parade down New York Citys Fifth Avenue, other areas either ignored or downplayed the African American contribution to the Allied victory. However, many blacks refused to quietly accept such slights. In St. Joseph, Missouri, for example, black veterans would not march at the back of a victory parade because it was incompatible with the democratic principles for which they had fought. The U.S. government also did not award any of the 127 Medals of Honor earned in WWI to an African American serviceman. This error was corrected on 24 April 1991, when President George Bush posthumously awarded the 128th WWI Medal of Honor to Corporal Freddie Stowers, a black soldier killed on 28 September 1918 while leading an assault on a German-held hill in France. 1919 During the summer following the Armistice of November 1918, racial violence spawned serious riots in Texas, Nebraska, Illinois, Washington, D.C., and other parts of the United States. This same year, 10 veterans were among the 75 African Americans lynched by white mobs. Unlike most confrontations before and during WWI, however, African Americans fought back in these postwar flare-ups. Some scholars attribute this new spirit of resistance to the changed attitudes of black veterans. Their experiences in the war as well as the lack of French racial prejudice toward them made many African American veterans unwilling to passively endure continued discrimination and ill treatment once they returned to the United States. 15 March 1919 Delegates representing AEF units met in Paris, France, to form the American Legion, a veterans organization. Black veterans were allowed to join, but only in segregated posts. 9 May 1919 The 369th Infantry Regiments former band leader, James Reese Europe, was stabbed to death by Herbert Wright, an unstable, disgruntled musician. In the few short months between the end of WWI and his death, Europe composed and recorded music based on his experiences during the Great War. Sung by Noble Sissle, who had been the drum major for the 369th, songs such as "On Patrol In No Mans Land" and "All of No Mans Land Is Ours" described the harsh combat conditions of the western front. 14 July 1919 The U.S. Army prohibited African American soldiers from participating in the Bastille Day victory parade held in Paris. June 1920 Congress passed the National Defense Act, which downsized the Army to 30,000 officers and enlisted men. All four of the Armys longstanding black units survived the cutbacks, primarily because white leaders feared the legal and social ramifications of eliminating them. Necessity also dictated the retention of both infantry and cavalry units to prevent the possibility of integrating brigades as well as to provide troops for duty in the Philippines. 1921 The Army disbanded the 3rd Battalion, 24th Infantry Regiment, which had been relegated to duty at various isolated posts in New Mexico in the aftermath of the deadly Houston riot of 1917. 1922 Joseph H. Ward was named medical officer-chief of the Veterans Administration (VA) hospital in Tuskegee, Alabama. He was the first African American appointed to head a VA hospital. 1922 As a result of severe cutbacks in military spending after WWI, the 24th Infantry Regiment was reduced to 828 men. The unit was stationed at Fort Benning, Georgia, where it helped transform the previously temporary home of the Armys Infantry School into a permanent facility. Kept segregated from the rest of the post, unit members were classified as riflemen and machine gunners, but they actually performed mostly manual labor: maintenance, construction, logging, deliveries, gardening, and cleanup details. Except for some instruction in marksmanship, close order drill, and military courtesy, black troops received little combat training between the wars. By 1934, the Army had made some attempts to improve the 24th Infantry Regiments ability to perform its military mission, but few real changes were implemented. 8 January 1922 The Armys highest ranking black officerColonel Charles R. Youngdied while serving as the U.S. military liaison in Nigeria. 1925 An Army War College study reported that African Americans would never be fit to serve as military pilots because of their supposed lack of intelligence and cowardice in combat. The famed "Tuskegee Airmen," however, would later completely disprove these questionable conclusions during combat in Europe. Between 1943 and 1945, the group earned 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses, 14 Bronze Stars, 8 Purple Hearts, 3 Distinctive Unit Citations as well as several other awards. 1929 Alonzo Parham entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, the first black cadet to be accepted since the graduation of Charles R. Young in 1889. He left after only 1 year. The next African American cadet was not admitted until 1932. 1932 The U.S. Navy again allowed African Africans to enlist, lifting the restriction in place since the end of WWI that excluded blacks from serving in this branch of the U.S. armed forces. However, they were only admitted into the predominantly Filipino Stewards Branch. 1936 Benjamin O. Davis, Jr., graduated from West Point, after enduring 4 years of "silencing." The academys fourth African American graduate, Davis was the first to be commissioned in the 20th century. Second Lieutenant Davis reported to Fort Benning to join the 24th Infantry Regiment, which continued to function primarily as a labor pool. 1936 James Johnson received an appointment to the U.S. Navy Academy, but he was forced to resign after only 8 months because of ill health. George Trivers followed in 1937, but left 1 month later for academic reasons. Both cadets suffered severe hazing by white midshipmen and discrimination by instructors. 1937 Willa Beatrice Brown, the first African American woman to get a commercial pilots license, and her flight instructor, Cornelius R. Coffey, co-founded the National Airmens Association of America to promote African African aviation. The following year, they established the Coffey School of Aeronautics, where Willa Brown served as director. The Army and Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) selected the Coffey School "to conduct the experiments that resulted in the admission of African Americans into the Army Air Forces." The school trained about 200 pilots between 1938 and 1945, some of whom later served as part of the famed "Tuskegee Airmen" when Coffey became a feeder school for the official flight program at Tuskegee Institute. 1939 After the number of African American soldiers had dropped to less than 4000 and in response to growing black demands, the U.S. Army began accepting black volunteers in proportion to their demographic presence (about 9 to 10 percent of the U.S. population). The only black regiments in the National Guard were the 369th New York, 8th Illinois, and the 372nd Regiment, which included men from Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Ohio, and the District of Columbia. African American servicemen represented only 2 percent of the nations fighting force before WWII. May 1939 The Committee for the Participation of Negroes in National Defense was formed. Headed by noted black historian Rayford W. Logan, who served as acting chair, the committee successfully helped to get nondiscrimination clauses inserted into the Selective Service Act passed in September 1940. May 1939 Sponsored by the National Airmens Association and aided by the Chicago Defender, a black newspaper, African American aviators Chauncey Spencer and Dale White lobbied for the inclusion of blacks as pilots in the Civilian Pilot Training Program then being debated in Congress. They won the support of several congressmen while in Washington, D.C., including that of Missouri Senator Harry S Truman. 27 June 1939 Congress passed the Civilian Pilot Training Act to create a pool of trained aviators in the event of war. Civilian schools, at least one of which was supposed to accept black pilots, provided the required flight training. Willa B. Brown lobbied for the inclusion of African Americans in both the training program and the Army Air Corps. At least seven different institutions enrolled blacks for flight training, but the Army Air Corps continued to exclude African- American pilots. 3 September 1939 Britain and France declared war after Germany invaded Poland, while President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced American neutrality in a fireside chat. During the years between WWI and WWII, the U.S. armed forces had continued to underuse and segregate African American servicemen. The Army restricted its African-American soldiers to all-black units, while the Navy relegated black sailors to menial labor and service tasks, primarily in the nonwhite Stewards Branch. The U.S. Marine Corps (USMC), like the Army Air Corps, continued its traditional exclusion of African Americans. 1939-40 To absorb the larger numbers of African Americans being admitted, the Army formed several new all-black units, primarily in the service and technical forces. The 47th and 48th Quartermaster Regiments formed in 1939 were followed in 1940 by the 1st Chemical Decontamination Company (1 August), the 41st General Service Engineer Regiment (15 August) as well as artillery, coastal artillery, and transportation units. 16 September 1940 President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Selective Training and Service Act, the first peacetime draft in U.S. history. The act contained an anti-discrimination clause and established a 10 percent quota system to ensure integration. Shortly thereafter, Assistant Secretary of War Robert Patterson issued a memo on segregation that seemingly contradicted the new legislations racial policy. Segregated troops remained official U.S. Army policy throughout World War II, because it did not consider racial separation to be discriminatory. The Army did attempt to dispel racist beliefs among its white officers by issuing Army Service Forces Manual M5, Leadership and the Negro Soldier. Classified "restricted," this publication tried to avoid condescension and stereotyping, while insisting on identical treatment for all soldiers, regardless of race. It also provided some sociological and historical information meant to eliminate erroneous beliefs concerning the use of African American combat troops. 17 September 1940 Black leaders met with the Secretary of the Navy and the Assistant Secretary of War to present a 7-point program for the mobilization of African Americans. Included were demands for flight training, the admission of black women into Red Cross and military nursing units, and desegregation of the armed forces. President Roosevelt issued a statement on 9 October 1940 that argued against the latter demand on the basis that it would adversely impact national defense. Although he promised to ensure that the services enlisted blacks in proportion to their demographic presence, Roosevelt basically continued policies dating back to WWI. Many African Americans were angered by the White Houses erroneous claim that the black leaders had approved the statement. However, additional political pressure by African Americans and some Republicans convinced Roosevelt to do more. Consequently, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr. was promoted to Brigadier General, flight training for blacks was planned, more blacks were drafted, Judge William H. Hastie was made a special aide to the Secretary of War, and a black advisor was appointed for the Selective Service Board. October 1940 African American servicemen in the U.S. armed forces prior to the nations entry into WWII in December 1941 totaled only 13,200 in the Army and 4000 in the Navy. During this month, the War Department established its basic racial policy by continuing segregation and by establishing a quota for enlisting blacks based on a percentage of their numbers in the general population. 1 October 1940 African American physician Dr. Charles Richard Drew, who pioneered a system for storing blood plasma thereby originating the "blood bank," served as director of the First Plasma Division Blood Transfusion Association. This British organization supplied plasma for British troops during WWII. In 1941, Drew was appointed to be the first director of the American Red Cross Blood Bank, which supplied blood to U.S. forces. He resigned from this position, however, to protest the organizations November 1941 decision to exclude black blood donors. Dr. Drews research was responsible for saving countless lives during WWII. 25 October 1940 Just before the November elections, President Roosevelt approved the promotion of Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., to the rank of brigadier general, making him the highest ranking African American in the armed forces. He began his military career with the 8th U.S. Volunteer Infantry (1898-99), then served with the 9th Cavalry (1899-1917) and other units before retiring in 1948. General Davis pioneered the way for the next generation of black officers who attained even higher positions of authority in the U.S. military. 1 November 1940 Judge William H. Hastie, dean of the Howard University Law School, assumed the position of Civilian Aid to the Secretary of War in Matters of Black Rights. The position was similar to that held by Emmett J. Scott during World War I. 18 December 1940 The U.S. Army Air Corps sent plans to Tuskegee Institute in Alabama concerning the training of African American pilots. On 6 January 1941, General Henry H. ("Hap") Arnold informed the Assistant Secretary of War about his decision to restrict the training of black flyers to Tuskegee where the necessary facilities to more quickly implement the program were available. In addition, the school was close enough to Montgomery to be supervised by the Maxwell Field Commander. Despite this decision, Arnold remained opposed to allowing African American pilots into the air corps, and he made several attempts to disband the program. By 1943, however, political considerations and increasing reports of the combat successes achieved by black aviators forced Arnold to stop tampering with the "Tuskegee Airmen." 1941 The U.S. Army activated the 366th Infantry Regiment, the first all-black Regular Army unit officered by African Americans only. 1941 Willa B. Brown became a training coordinator for the Civil Aeronautics Administration and a teacher in the Civilian Pilot Training Program. January 1941 Black labor organizer and civil rights leader (and later politician, writer, and professor) Ernest Calloway was the first black to refuse to be inducted because he objected to the Armys racist segregation policy. He was a member of the Conscientious Objectors Against Jim Crow, a group which claimed African Americans should be exempt from military service because of discrimination. Calloways protest and subsequent imprisonment generated a lot of national publicity. Although this particular group disbanded after Calloway was incarcerated, over 400 other black men also became conscientious objectors during WWII. Some were members of the Nation of Islam who refused induction on religious grounds, while others like William Lynn refused to serve because the quota system established by the armed forces contradicted the anti-discrimination clauses of the September 1940 Selective Service and Training Act. January 1941 Labor and civil rights leader, A. Philip Randolph, president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, proposed a massive March on Washington in July 1941 to protest unfair labor practices in the defense industry and the militarys discrimination against African Americans. During WWI, Randolph had not endorsed other black leaders calls to put aside their own grievances and unite behind the war effort, stating "that rather than volunteer to make the world safe for democracy, he would fight to make Georgia safe for the Negro." His demands for full black participation continued in WWII. 9 January 1941 Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson formally approved the establishment of the flight training program at Tuskegee Institute. 13 January 1941 The U.S. Army established the 78th Tank Battalion, the first black armor unit. The first African American tankers reported to Fort Knox, Kentucky, to begin armored warfare training in March 1941. The 78th was redesignated on 8 May 1941 as the 758th Tank Battalion (Light). It was the first of three tank battalions comprising the 5th Tank Group, which was made up of black enlisted men and white officers. The other two tank battalions were the 761st and 784th. Initially inactivated on 22 September 1945 at Viareggio, Italy, the 758th was reactivated in 1946 and later fought in the Korean War as the 64th Tank Battalion. February 1941 The 1st Battalion, 351st Field Artillery Regiment was activated at Camp Livingston, Louisiana, as part of the 46th Field Artillery Brigade. Redesignated the 351st Field Artillery Battalion in 1943, the unit arrived in Europe in December 1944. The African American enlisted personnel were officered by 16 blacks and 15 whites. While stationed in England from December 1944 to February 1945, the 351st Field Artillery Group-Coloreds 50-man Caisson Choir sang for the British public in such notable places as Westminster Abbey and St. Pauls Cathedral. After being transferred to France in March 1945, the unit was attached to the 9th U.S. Army. While engaged in fighting with the Germans, the 361st fired over 6200 rounds of 155mm Howitzer artillery ammunition into enemy territory. 25 June 1941 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 which reiterated the federal governments previously stated policy of nondiscrimination in war industry employment. It also created a Committee on Fair Employment Practice to oversee the application of the presidents directive and to expand new job opportunities for black workers. This action was in keeping with a promise made to A. Philip Randolph if he would call off his planned "March on Washington" to protest discrimination and segregation. 29 June 1941-16 November 1944 While on assignment with the Armys Inspector General, Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., completed several notable inspections involving black troops stationed at northern and southern posts. In a memorandum of 9 November 43, Davis pointed out the nearly impossible task required of African American soldiers in developing "a high morale in a community that offers him nothing but humiliation and mistreatment." He reported that instead of working to eliminate "Jim Crow" laws in the military, "the Army, by its directives and by actions of commanding officers, has introduced the attitudes of the Governors of the six Southern states, in many of the other 42 states of the continental United States." He also conducted several important inquiries into racial clashes between white soldiers or civilians and black soldiers stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Alexandria, Louisiana; Fort Dix, New Jersey; Selfridge Field (now Air Force Base), Michigan; and Camp Stewart, Georgia. In his reports, Davis recommended that African American soldiers gradually be removed from southern posts and that black officers be assigned to command black troops. General Davis also represented the War Department at numerous functions involving black civilians, such as war bond rallies or speeches given to war industry workers. July 1941 The Army opened its integrated officers candidate schools. For the first 6 months, however, only 21 of the more than 2000 men admitted were black. Whites protested the policy and some black leaders demanded a quota be established to ensure parity, but the Army justified its policy of ignoring race in regard to officer training on the grounds of efficiency and economy. Unfortunately, race still continued to determine assignments after newly commissioned officers graduated. Too often more qualified African American officers were put in charge of service units, while less qualified white officers continued to be assigned to black combat units. The degree of authority and respect given to black officers also remained a serious problem, since African American officers were unable to command even the lowest ranking white soldiers. 19 July 1941 The U.S. Army Air Corps began training African American pilots at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Actual flight instruction began on 25 August. The Tuskegee Institute, which prepared the 926 members of the famed "Tuskegee Airmen" for combat in WWII, remained the only official military flight training school for black pilots until its program closed with the graduation of the last class on 26 June 1946. 4 August 1941 The first commanding officer of Huntsville Arsenal (Alabama), Colonel Rollo C. Ditto, arrived and broke ground for the initial construction of the installation. Huntsville Arsenal, which was part of the Chemical Warfare Service, was the sole manufacturer of colored smoke munitions. It also produced gel-type incendiaries and toxic agents such as mustard gas, phosgene, lewisite, and tear gas. The Army broke ground on neighboring Redstone Arsenal on 25 October 1941. This Ordnance Corps installation manufactured chemical artillery ammunition, burster charges, rifle grenades, and various types of bombs. African American men and women worked at both arsenals during WWII. By May 1944, when civilian employment reached its wartime peak of 6,707 men and women, blacks represented 22 percent of the work force at Huntsville Arsenal. |

Part I - Part II - Part III - Part IV

![]()

Visit Our Other Sites