FRtR > Outlines > American Literature > The Romantic Period, 1820-1860: Fiction Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

An Outline of American Literature

by Kathryn VanSpanckeren

The Romantic Period, 1820-1860: Fiction: Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864)

*** Index ***

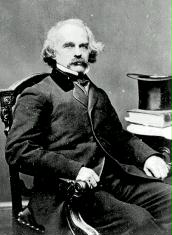

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a fifth-generation American of English

descent, was born in Salem, Massachusetts, a wealthy seaport

north of Boston that specialized in East India trade. One of his

ancestors had been a judge in an earlier century, during trials

in Salem of women accused of being witches. Hawthorne used the

idea of a curse on the family of an evil judge in his novel

The

House of the Seven Gables.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a fifth-generation American of English

descent, was born in Salem, Massachusetts, a wealthy seaport

north of Boston that specialized in East India trade. One of his

ancestors had been a judge in an earlier century, during trials

in Salem of women accused of being witches. Hawthorne used the

idea of a curse on the family of an evil judge in his novel

The

House of the Seven Gables.

Many of Hawthorne's stories are set in Puritan New England, and

his greatest novel, The Scarlet Letter (1850), has become

the

classic portrayal of Puritan America. It tells of the passionate,

forbidden love affair linking a sensitive, religious young man,

the Reverend Arthur Dimmesdale, and the sensuous, beautiful

townsperson, Hester Prynne. Set in Boston around 1650 during

early Puritan colonization, the novel highlights the Calvinistic

obsession with morality, sexual repression, guilt and confession,

and spiritual salvation.

For its time, The Scarlet Letter was a daring and even

subversive

book. Hawthorne's gentle style, remote historical setting, and

ambiguity softened his grim themes and contented the general

public, but sophisticated writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson and

Herman Melville recognized the book's "hellish" power.  It treated

issues that were usually suppressed in 19th-century America, such

as the impact of the new, liberating democratic experience on

individual behavior, especially on sexual and religious freedom.

It treated

issues that were usually suppressed in 19th-century America, such

as the impact of the new, liberating democratic experience on

individual behavior, especially on sexual and religious freedom.

The book is superbly organized and beautifully written.

Appropriately, it uses allegory, a technique the early Puritan

colonists themselves practiced.

Hawthorne's reputation rests on his other novels and tales as

well. In The House of the Seven Gables (1851), he again

returns

to New England's history. The crumbling of the "house" refers to

a family in Salem as well as to the actual structure. The theme

concerns an inherited curse and its resolution through love. As

one critic has noted, the idealistic protagonist Holgrave voices

Hawthorne's own democratic distrust of old aristocratic families:

"The truth is, that once in every half-century, at least, a

family should be merged into the great, obscure mass of humanity,

and forget about its ancestors."

Hawthorne's last two novels were less successful. Both use modern

settings, which hamper the magic of romance. The Blithedale

Romance (1852) is interesting for its portrait of the

socialist,

utopian Brook Farm community. In the book, Hawthorne criticizes

egotistical, power-hungry social reformers whose deepest

instincts are not genuinely democratic. The Marble Faun

(1860),

though set in Rome, dwells on the Puritan themes of sin,

isolation, expiation, and salvation.

These themes, and his characteristic settings in Puritan colonial

New England, are trademarks of many of Hawthorne's best-known

shorter stories: "The Minister's Black Veil," "Young Goodman

Brown," and "My Kinsman, Major Molineux." In the last of these, a

na�ve young man from the country comes to the city -- a common

route in urbanizing 19th-century America -- to seek help from his

powerful relative, whom he has never met. Robin has great

difficulty finding the major, and finally joins in a strange

night riot in which a man who seems to be a disgraced criminal is

comically and cruelly driven out of town. Robin laughs loudest of

all until he realizes that this "criminal" is none other than the

man he sought -- a representative of the British who has just

been

overthrown by a revolutionary American mob. The story confirms

the bond of sin and suffering shared by all humanity. It also

stresses the theme of the self-made man: Robin must learn, like

every democratic American, to prosper from his own hard work, not

from special favors from wealthy relatives.

"My Kinsman, Major Molineux" casts light on one of the most

striking elements in Hawthorne's fiction: the lack of functioning

families in his works. Although Cooper's Leather-Stocking

Tales

manage to introduce families into the least likely wilderness

places, Hawthorne's stories and novels repeatedly show broken,

cursed, or artificial families and the sufferings of the isolated

individual.

The ideology of revolution, too, may have played a part in

glorifying a sense of proud yet alienated freedom. The American

Revolution, from a psychohistorical viewpoint, parallels an

adolescent rebellion away from the parent-figure of England and

the larger family of the British Empire. Americans won their

independence and were then faced with the bewildering dilemma of

discovering their identity apart from old authorities. This

scenario was played out countless times on the frontier, to the

extent that, in fiction, isolation often seems the basic American

condition of life. Puritanism and its Protestant offshoots may

have further weakened the family by preaching that the

individual's first responsibility was to save his or her own

soul.

Available on the Internet

- The Scarlet Letter

- The House of the Seven Gables

- The Blithedale Romance

- Twice-Told Tales

- Mosses from an Old Manse

- The Life of Franklin Pierce

- Other Writings

*** Index ***

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a fifth-generation American of English

descent, was born in Salem, Massachusetts, a wealthy seaport

north of Boston that specialized in East India trade. One of his

ancestors had been a judge in an earlier century, during trials

in Salem of women accused of being witches. Hawthorne used the

idea of a curse on the family of an evil judge in his novel

The

House of the Seven Gables.

Nathaniel Hawthorne, a fifth-generation American of English

descent, was born in Salem, Massachusetts, a wealthy seaport

north of Boston that specialized in East India trade. One of his

ancestors had been a judge in an earlier century, during trials

in Salem of women accused of being witches. Hawthorne used the

idea of a curse on the family of an evil judge in his novel

The

House of the Seven Gables.

It treated

issues that were usually suppressed in 19th-century America, such

as the impact of the new, liberating democratic experience on

individual behavior, especially on sexual and religious freedom.

It treated

issues that were usually suppressed in 19th-century America, such

as the impact of the new, liberating democratic experience on

individual behavior, especially on sexual and religious freedom.