|

|

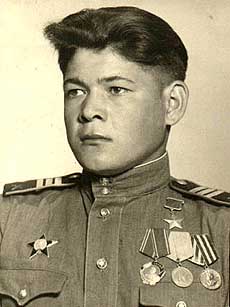

Gennadii Schutz, 1945 |

I was 17 in June 1941. On the 18th we had a graduation ceremony, and on the 22nd a football game between our district, on whose team I played, and the neighboring one. We were loosing. And then my brother comes running and shouts: "Genka, the war has started!" I say: "What war? Don't you see we're loosing!" And later that night in the club, where we watched a movie, unexpectedly the screen was pulled up and a platform rolled out. Some district committee worker addressed us with a speech that the war had started and asked all KOMSOMOL members to report to the Party district committee. We went there during the night. I wrote an application and asked to be sent to the front as a volunteer, but since I was born in '24, which wasn't due for conscription yet, they sent me to procure hay for the army instead of the front. They put me in charge of 13 girls, who couldn't do almost anything - and so I ran from one to another: "Genka, fix the scythe! Genka, my scythe is stuck in a hummock! Genka, sharpen my scythe!" I was exhausted with them.

That same summer I enrolled in the Tomsk Railway Institute. I only studied one month at the institute, and then they sent us home. In January 1942, when I had become 18, I was drafted. They sent our entire group of conscripts to Moscow, where we were put into a sorting camp, which was located in Izmailovo. When our crew arrived a sergeant major approached me and asked: "How many classes have you finished?" I said: "10" He: "Do you know trigonometry?" "Yes" "Want to become an AA gunner?" I said: "Gladly!" And so, in April 1942, I was put into a battery of small caliber anti-aircraft artillery. They said they'd be training us until August. In the beginning of June we received our AA guns - 37mm guns Model 1939 with the rate of fire of 160 rounds per minute. But in reality, after 75-100 shots they heated up so much that they jammed.

The battery commander assigned our duties and I became a range finder. As it turns out, stereoscopic perception, that is the ability to differentiate distances to objects and determine their relative distance, is particularly subjective. The test was extremely simple: the commander pointed at a tree and a pole, which were approximately 800 meters away from us, and asked which one was farther. Since I had responded correctly I became a range finder. At that time our battery consisted of four guns which were positioned as if at the vertices of a square with sides of 100-150 meters. The command post was located at the center of the square and consisted of waist high foxholes for the spotter, the range finder, and the commander. The battery commander and the guns were connected by wire communications. In reality, during battle, there was no possibility to give voice commands because of the din of salvos, that's why we developed a special system of prearranged signals.

Hands on training, May '46. Germany.

(Although the picture was taken after the war, it gives full impression of how the battery command post worked). |

The battery worked in the following manner. The spotter, armed with binoculars, after having located approaching enemy aircraft, determined their number. In the ideal case that was possible from five kilometers away. I, a range finder, determined the distance to the target and continually informed the commander about its change. In turn, the commander allocated targets between guns and chose the time to fire and the type of fire - single shots, short, or long bursts. Usually the fire was opened from the distance of 2000-2200 meters in short bursts. Long bursts were used against low flying targets. We shot using regular HE shells. Of course, we were also allocated AP shot, but they were rarely used and then only to fire at ground targets. A gun's crew consisted of 8 men - commander, two gunners numbers 1 and 2, range finder, spotter for the direction and velocity of target's flight, loader, and two ammo carriers (if the firing was conducted in long bursts, then one man was not able to keep up, the clips disappeared as if into a meat grinder). The Number 1 aimed the gun in the vertical until the horizontal line in the collimator overlaid the target, the Number 2 in the horizontal until the vertical line in the collimator overlaid the target, Number 3 set the distance and velocity of the target which were relayed by the battery commander, the spotter, by turning the fly-wheel, tried to guess the aircraft's direction, the commander, after having determined that the target was acquired reported to the command post and at battery commander's order the Number 2 opened fire. Although, experienced gunners usually aimed by the tracer shells. This ability was worked on during the constant training exercises between air raids or during sentry duty (one gun was always on sentry in the battery).

A gun crew of Sergeant Ivan Shapin Standing from left to right: ammo carrier, range finder, loader, spotter of direction, ammo carrier, commander; sitting: 1st number, 2nd number.(From the book by A. Grechko "Bitva za Kavkaz"; "The battle for Caucasus".) |

So, returning to 1942, we didn't even have time to finish mastering the guns, when an order arrived about our transfer to the front. In the beginning of July our 241st Army Anti-Aircraft Artillery Regiment, consisting of 4 batteries and 2 machine gun companies armed with DShK's, was transferred to the Voronezh Front. We were studying the guns right on the railroad cars, and once, during a training session, the gunners fired a shot which almost killed our battery commander - the shell flew over his head. At the Serebriannye Prudy station we were bombed for the first time. I jumped head first into the closest bushes and sat there shaking with fear until the planes left. And already at the Anna station we received our real baptism by fire.

Until the end of summer we kept falling back with the ground forces until the front stabilized on the river Don, on whose bank we were deployed right up to the beginning of the counteroffensive. It was a difficult time. Ammo was scarce. We were poorly fed - for the first and second course soup or porridge from whole grain wheat, or peas freshly cooked on Uzbek cotton oil, which looked like rust. And one time we didn't even have salt - that was real torture. We were fed this way for about a month.

That was the last year when the Germans tried to fight according to a schedule. They almost never bombed at night, but the raids of their aviation started in the morning. There was scorching heat - half past eight in the morning, heat, stink, the first group of bombers comes in. They bomb both us and the infantry. In 30-40 minutes, it's the second group. After the third bombing raid, if they bombed successfully, we all would be black from soot and dust.

After one such raid the regiment's komsorg (KOMSOMOL organizer - trans.) was wounded and the political department appointed me acting komsorg. Anytime I had a free minute, I visited our batteries, talked about the situation at the front, about the actions of our allies. The men were mostly illiterate - our

|

Sergeant Gennadii Shutz, 1942 |

entire battery had only two men with secondary education, and the rest either 7 years or only 4 grades. Of course you had to talk to them. After all, the Germans also conducted their own propaganda - dropped leaflets. I remember some of them well. The first one, this two page leaflet in A4 format, on chalk paper. There was a circle cut out on the first page so that the Soviet coat of arms could be seen on the third page. When you open it, there is a caption below the coat of arms: "Hammer to the left, sickle to the right, this is our Soviet coat of arms. Reap if you want, or hammer if you want, you'll still get" and three dots (To any Russian speaker, the obvious rhyme is a vulgar word for the male sexual organ, which in this case would mean "you'll get nothing" - trans.) That was low, of course. Apparently, the Germans were informed that we had shortages of paper, and that we didn't even have anything to roll a cigarette with, so the second leaflet was specially printed on cigarette paper in the hope that the soldiers would use it for cigarettes and read it at the same time. It read: "Only Timoshenko with Yids the heroes want war. You retreat only because Stalin killed 130 thousand best commanders and political officers." Or there was a leaflet showing how well some surrendered Ivanov, Petrov, Sidorov lived. They were pictured sitting there, playing an accordion, smiling. I had to explain that all that was lies.

When the Stalingrad offensive started we reached the Cossack villages of Kantimirovka and Buturlinovka. During the offensive our life was also not too sweet - our guns were pulled by Willys jeeps which coped well on flat ground. But when driving downhill, a gun with the boxes of shells loaded on it aimed to push the car off the road. Only in 1944 we got Dodge 3/4, and then two axle Chevrolet and �Studebaker US6x6�, which usually pulled 2 guns. But back then only the Willys could get us through.

After the end of the Battle of Stalingrad I was sent to an artillery school in Tomsk, and then to Irkutsk, where I finished it. Already in the fall of 1943 I found myself in Leningrad. A small pre-revolutionary "ovechka" ("sheep" in Russian, comes from the locomotive's designation - "OV" - trans.) steam engine brought us, having flown at full speed through the corridor breached between Volkhov and Leningrad in '43. I was sent to the 32nd Division from the transfer point, where I was put in charge of a platoon (2 guns). At that time an enlargement of artillery units occurred and our 32nd Anti-Aircraft Artillery Division RGK (RGK - C-in-C's Reserve - trans.) had 4 regiments, of them 3 regiments (1387th, 1393rd, and our 1413th) were MZA (Small Caliber AAA) and one 1387th Regiment SZA (Medium Caliber AAA), armed with 85mm guns. The reorganization also involved the batteries - they now contained 6 artillery pieces. The guns in a position were now arrayed in a hexagon, with the distance between them of 150-200 meters. That was according to the manual, but in a combat environment we sometimes used different deployments, for example a line when guarding columns.

We struck in the month of January. Liberated Gatchina and almost reached Pskov. During the offensive the regiment covered the 46th Luga Rifle Division. Already at Pskov I was appointed battery commander. I remember the day of the appointment very well. It was in the beginning of February. I had just arrived at the 4th battery, which was put under my command, and went to meet the personnel. At that time the battery, with the auxilary services, consisted of 84 men. In addition, the platoon commanders were all lieutenants, while I was a junior lieutenant. Basically, I was greeted with distrust. And then a raid happened: 30-35 Ju-87. Everyone was looking at me - to see how I was going to command. You ask if I could keep from opening fire? I could, but it was considered as cowardice among AA gunners. We had a law - while a raid continues no one, from ammo carriers to the battery commander, could even bend down. You had to keep doing your duties. The main thing was not to lose your nerve. After all, there were some who stuck their heads under the gun's carriage out of fear. So, we went through that baptism by fire successfully. We didn't shoot anything down, but we scattered the aircraft, they didn't go for a second attempt, and we saved the crossing. That's a contribution. Also, no one was killed.

Overall, from the beginning of 1944 until May 1945 my battery shot down 13 aircraft, and we were in one of the first places in the division by performance. It doesn't seem like much, right? But what is our task? Not to let the enemy bomb while aiming at the guarded objective. Sure, it's great to shoot a plane down, but that's not the main thing, the main thing was that the covered infantry, tanks, or a crossing don't get hurt from the raid. At Stalingrad our regiment shot down around 100 planes in 2 months. But those were Ju-52, which supplied the encircled 6th Army, it was easy to shoot them down. But to shoot down a Ju-87 - that was very difficult. It was the most perfidious and dangerous dive bomber the Germans had. Although not very fast, its bombing was very precise. That's why we shot at it at the moment when it climbed before the dive. It's scary for the pilot, he sees that he's being shot at. He'll drop the bomb anyway, but to make him err, drop the bomb sooner or too late - that was our task. But when we did see that we shot down a plane, we immediately sent a gun mechanic on a "Willys" to the spot of the crash, to take the factory plate as material evidence. It was also useful to get a confirmation from the guarded detachment. Of course, it happened that the plane would fall already in the enemy territory, then it was counted only if such confirmation was given. And so, for the first 5 aircraft I got the Order of the Red Star, for the next 5 - Order of the Patriotic War 2nd Degree. I was also decorated with the medals "For Defense of Leningrad", "For the Capture of Berlin", and "For Victory over Germany".

From Pskov we were transferred to Vyborg. Again we broke through the enemy defenses and advanced for a hundred kilometers without a hitch, thought that it would continue, but no - before Vyborg we ran into strong resistance and halted, and the entire army kept going under its own momentum and an accumulation of people and vehicles occurred on the Primorskoye highway. I dispersed the battery by platoons along the column over almost 2 kilometers. The Germans didn't make us wait. During the raid bomb fragments wounded practically the entire crew of one of the guns. Then the gun commander Ermeneyev, being wounded himself, replaced a gunner and with another guy shot down 3 planes coming out of a dive, and scattered the rest, for which he was awarded and became a Hero of the Soviet Union. That was the official story. But unofficially, he did have a wound, but it was light, and he didn't shoot down all 3 - we put them down on him. The others were also firing, and the planes fell beyond the front line. But still it was a heroic feat - he didn't let them bomb the column, otherwise it would've been a mess.

Hero of the Soviet Union "Comrade senior lieutenant, remember and don't forget your Hero. Viktor Ermeneyev. A gift to remember me to the battery commander Sr. Lt. Gennadiy Shutz. Stendal (Germany) 7.10.45 (October 7, 1945) |

We recommended him for a decoration, but not the Hero, since for the Hero you had to write a separate recommendation. In 1944 it was decided to mark the Artillery Day on the anniversary of the counteroffensive at Stalingrad, November 19th. Apparently, there was Stalin's order to recommend one or two men for a Hero of the Soviet Union from each type of artillery units. In the fall I was called to the regiment HQ and asked to write a recommendation for Ermeneyev. And thus my battery came to have a Hero.

There, at Vyborg, we also had an unpleasant incident. During the offensive I became acquainted with a major, commander of the VNOS service (Aerial Reconnaissance, Warning, and Communication). Only girls served there, and he was in command of them. And so, they had a balloon, like a sausage, on which this major went up with a radio to maybe 800 meters to spot for artillery. And one time we saw a "messer" (Messerschmitt - trans.) coming at this balloon at extremely low height. We opened fire, so that it wouldn't break through and set the "sausage" on fire. It must be said that it's very difficult to shoot at a low flying fast target, everything depends on the coordinated work of the gunners, who intuitively select the moment to fire. And suddenly I see our shell pierce the balloon, it bursts into flames and starts falling. That guy that was in it managed to bail out and open the parachute when he was already close to the ground . "Well," I'm thinking, "that's it - court martial." And here our regiment commander comes in a "Willys" - an unpleasant man. Says: "Write a recommendation, the commander saw how you shot down a 'messer'." I say: "What 'messer'? I shot down our 'sausage'!" But he pushes his own line. I think he was hoping to get his own decoration. I sent the Willys to find out if the major's alive. They came back with him. Thank God he's alive! But he's hurt badly - arms scratched, abrasions on the face. Then he starts swearing at me! I say: "Well, you saw it yourself - we were chasing the 'messer' away." We drank a cup of alcohol with him, made up, and afterward, while the offensive was continuing, we met more than once. Of course, anything could happen during the war. Another time we fired at our own fighter. It's a good thing we didn't shoot it down. Of course, we did have an identification system, YaSS (I am Our Airplane), but it was rather primitive - various rolling of the wings during the day, and a combination of running lights during the night. The signals were changed every day, which severely complicated my job as a battery commander.

Then we advanced westward along the shore of the Bay of Riga. One time we were sitting on the beach, playing cards with some girls. And then the look-out shouted: "Water target!" I looked and saw three German torpedo boats approaching the shore. I called an alert and we started letting them get closer, but from 800 meters they opened fire. I saw one explosion, another. And we replied from all six guns. Basically, we chased them off and went to finish the game. Soon we liberated the city of Tartu. It was a warm August night when we entered this city, and I got an impression that the war bypassed it - no shots could be heard, traces of battles were absent from the streets. We halted, and I decided to go gather some raspberries that grew in the garden in front of the house. Picking the large, tasty raspberries, I parted some bushes and saw a dead woman lying flat on the ground. This contrast between beauty and silence on one side and death on the other has imprinted itself in my memory for the rest of my life.

We crossed the border with Germany in the region of the Netze River at Kostschin (Kostrzyn). We were driving at night over the site of yesterday's battles. Exhausted soldiers slept in the back of the truck. Suddenly I saw a plywood arch over the road and a sign on it in large black letters. I read it and my skin became covered with goose bumps: "Here it is - the criminal Germany." I called my platoon commanders. The soldiers were woken up. Here, I say, we're entering the fascist beast's lair. In the morning the regiment commander arrived. We had it set up so that a look-out watches both the air and the road, expecting superiors. If he sees a commander's "Willys" he would also command "Alert!", same as during an air raid. The commander asks: "What did you feed the soldiers today?" "Well, porridge, as always" - I reply. "Sergeant major, come here. What did you feed the soldiers?" "Porridge, Comrade Colonel." "Porridge, porridge... I was at Terekhov's battery, they already procured pork, or whatever. Take a Studebaker or a Chevrolet and drive to a farm. Take everything they got." It must be said that beyond Netze the population in the radius of 20 km ran away, abandoning hungry farm animals. So our commanders were pushing us to pillage. Although, this ceased shortly because an order of the Front Commander Zhukov came out, saying something like: "We are a liberator army, which brought liberation to the German people, and we must treat the German people same as our own." But try to explain to simple Russian soldiers, who had relatives hanged or shot, houses destroyed, that they must forget everything at once?! It's impossible! The men were indignant: "Why am I supposed to forget what the Germans have done with my land, my relatives?" This transition was very painful. Because from the very Stalingrad to Germany's border we were advancing under the slogan: "Kill a German!" I still see Ilya Erenburg's articles in front of my eyes. You also have to keep in mind that the replacements in my battery by that time were mostly criminals, released due to amnesty. There was a case when my soldier, a criminal like that, raped a mother and daughter in a cemetery. I had to defend myself, write a report, SMERSH (stands for "Death to Spies", wartime military counter-intelligence organization - trans.) got interested, and he was put before a court martial. But there weren't any mass cases.

Well then, we captured Berlin, then Magdeburg,

crossed Elba, and reached Stendal. There we stopped and lived for about a year.

That's how the war ended.

| Recorded

and edited by Artem Drabkin Translated by Oleg Sheremet Photos from the archive of G. Shutz |

|

|

|

|