THE GHOSTLY SPHINX OF METEDECONK

By: Stephen Crane

[One Must Needs Flee for His Life When She Confronts Him. - A Mourning Thing of the Mist. - What Comes of Pouting at the Pleadings of One's Sailor Love]

Metedeconk, N.J., Dec. 28. - About a mile south of here, on the low brown bluff that overlooks the ocean, there is an old house to which the inhabitants of this place have attached a portentous and grewsome legend. It is here that the white lady, a moaning, mourning thing of the mist, walks to and fro, haunting the beach at the edge of the surf in midnight, searches for the body of her lover. The legend was born, it is said, in 1815, and since that time Metedeconk has devoted much breath to the discussion of it, orating in the village stores and haranguing in the post office, until the story has become a religion, a sacred tale, and he who scorns it receives the opprobrium of all Metedeconk.

It is claimed that when this phantom meets a human being face to face she asks a question - a terrible, direct interrogation. She will ask concerning the body of her lover, who was drowned in 1815, and if the chattering mortal cannot at give her an intelligent answer, containing terse information relating to the corpse, he is forthwith doomed, and his friends will find him the next day lying pallid upon the shore. So, for fear of being nonplussed by this sphinx, the man of Metedeconk, when he sees white at night, runs like a hare.

There have bee those who have come here and openly derided the legend, but they have always departed wiser. Once a young man, who believed on the materialism of everything, came to town and perambulated up and down the beach during three midnights. He had requested the inhabitants to bring forth their phantom. She did not appear. During some following days the young man poked all the leading citizens in the ribs and laughed loudly, but he was whipped within an inch of his life by an old retired sea captain named Josiah Simpson. Since then the legend has obtained a much wider credit, and for miles around Metedeconk the people evince a great faith in it.

[The Fisherman's Fright]

The last man to assert definitely that he had encountered the specter is a bronzed and blasé young fisherman, who assures the world that the matter is its believing his story is of no consequence to him. He relates that one night, when swift scudding clouds flew before the face of the moon, which was like a huge silver platter in the sky, he had occasion to pass this old house, with its battered sides, caving roof and yard overgrown with brambles. The passing of the clouds before the moon made each somber shadow of the earth waver suggestively and the wind tossed the branches if trees in strange and uncouth gestures. Within the house the old timbers creaked and moaned in a weird and low chant. By a desperate effort the fisherman dragged himself past this dark residence of the specter. Each wail of the old timbers was a voice that went to his soul, and each contortion of the shadows made by the wind waved trees seemed to him to be the movement of a black and sinister figure creeping upon him.

But when it was when he was obliged to turn his back upon the old house that he suffered the most agony of mind. There was a little patch of flesh between his shoulder-blades that continually created the impression that a deathlike hand was about to be laid upon him. His trembling nerves told him that he was being approached by a mystic thing. He gave an involuntary cry and turned to look behind him.

There stood the ghostly form of the white lady. Her hair fell in disheveled masses over here shoulders, her hands were clasped appealingly, and here large eyes gleamed with the one eternal and dread interrogation. Her lips parted, and she was on the very verge of propounding the awful question, when the fisherman howled and started wildly for Metedeconk. There rang through the night the specter's cry of anger and despair, and the fisherman, although he was burdened with heavy boots, ran so fast that he fell from sheer exhaustion upon the threshold of his home. From that time forward it became habitual with him to wind up his lines when the sun was high over the pines of the western shore of Barnegat, and to reach his home before the chickens had gone to bed.

[Source of the Mystery]

It seems long ago a young woman lived in this house which then was gorgeous with green blinds and enormous red chimneys. The paths in the grounds had rows of boxwood shrubbery lined down their sides with exquisite accuracy, and each geometrical flower bed upon the lawn looked like a problem in polygons. The maiden had a lover who was captain of a ship given to long voyages. They loved each other dearly, and, in consequence of these long voyages, they were obliged to part with protestations of undying affection about three times a year. But once when the handsome sailor luffed his ship into the wind and had himself rowed ashore to bid goodbye to his love, she chose that time to pout. He spent a good deal of time in oration and argument, he proved to her in sixty ways that she was foolish to act thus at the moment of his departure, but she remained perverse, and during his most solemn abjurations she lightly and blithely caroled a little ditty of the day. Finally in despair he placed his hand upon his lacerated heart and left for Buenos Ayres.

But his ship had not passed Absecon Inlet before the maiden was torn with regret and repentance, and by the time the craft was a white glimmer upon the edge of the horizon she began to mourn and mourn in the way that has since become famous. As the days passed, her sorrow grew, and the fishermen used often to see her walking slowly back and forth, gazing eagerly into the southeast for the sail that would bear her lover to her. During great storms she never seemed able to remain quietly in the house, but always went out to watch the white turmoil of the sea.

The round, tanned cheeks grew thin and pale. She became frail, and would have appeared always listless if it were not for the feverish gleam of those large eyes, which eternally searched the sea for a belated sail.

[The Storm's Finale]

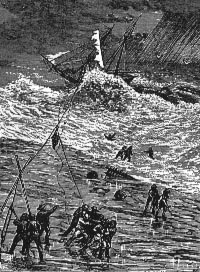

One winter's day a storm came from the wild wastes of the unknown and broke upon the coast with extraordinary fury. The tremendous breakers thundered upon the beach until it seemed that the earth shook from the blows. Clouds of sand whirled along the beach. The wind blew so that it was nearly impossible to make headway, but still the young girl came out to stare at the impenetrable curtains of clouds in the southeast.

That evening as she made her difficult way along the beach, a rocket went up at sea, leaving for a moment a train of red sparks across the black sky. Then she knew that sailor lads were in peril. After a time a green light flashed over the water, and finally she could perceive a large ship on the bar. Above the roar of the waves she imagined she could hear the cries of men.

The fishermen, notified by the rocket, came to the shore by twos and threes. No boat could live in such a sea and the sailors of the ship were doomed. The fishermen bustled to and fro, impatiently shouting and gesturing, but in those days their greatest efforts could consist in no more than providing fires, drink, and warm blankets for any who by some astounding chance should escape the terrible surf. From time to time seamen tried to swim to the shore, and for an instant a head would shine like a black bead on this wild fabric of white foam. Bodies began to wash up and the fishermen, congregating about huge fires devoted their attention to trying to recall the life in these limp, pale things that the sea cast up one by one.

The maiden paced the beach praying for the souls of the sailor who, upon this black night, were to be swallowed in a chaos of waters for the unknown reasons of the sea.

Once she espied something floating on the surf. Because of the small grewsome wake, typical of a floating corpse, she knew what it was and she awaited it. A monstrous wave hurled the thing to her feet and she saw that her lover had come back from Buenos Ayres.

This is the specter that haunts the beach at the edge of the surf and

who lies in wait to pour questions into the ears of the agitated

citizens of Metedeconk.

[EDITOR'S NOTE: Stephen Crane is one of the most celebrated writers associated with the State of New Jersey. He was born the day after Halloween in 1871, in Newark, the last of fourteen children. His father, a minister, moved the family to Paterson in 1876, and after his death in 1880, Stephen's widowed mother moved the family to Asbury Park, where he remained until he entered college in 1890. After only one semester at Syracuse University, Stephen began working for the New York Tribune as a journalist, and as author of a few well reviewed, but not commercially successful novels. In 1893, he wrote the "The Red Badge of Courage" which was a bestseller here and in Europe. He continued to pen novels, poems, short stories, and newspaper articles at a tremendous pace until his death in 1900, at the age of 29, from tuberculosis. The only memorial to him in New Jersey is the Stephen Crane Museum, 508 Fourth Avenue, Asbury Park, which is the house where he grew up. A wall that commemorated his birthplace in downtown Newark was bulldozed in 1996 to make way for a new parking lot. Metedeconk was a fishing and shipping village located at the mouth of the Metedeconk River in what is Brick Township today.]

SOURCES

BOOKS

Stephen Crane: Uncollected Writings

Edited by: Olov W. Fryckstedt

Uppsala, 1963

PERIODICALS

Proceedings of the New Jersey Historical Society

"Jersey Gothic"

By: Oral S. Coad

Volume 84, Number 2, 1966

"Stephen Crane's New Jersey Ghosts"

By: Daniel G. Hoffman

Volume 71, 1953

SPECIAL THANKS TO

The New Jersey Historical Society

Newark, NJ

The Newark Public Library

Newark, NJ

BACK TO HALLOWEEN TALES - 2001