THE DEATH OF A PRESIDENT

Click On Anything In Color To View Photo Or Image

It was a warm evening on September 5, 1881, as two thousand men, some

railroad workers and others volunteers from the area, struggled

in the heat to complete their task before morning. Food stores and

hotel kitchens stayed open throughout the night to nourish the men,

and the women from town served the food and drink that was

transported to the work site. As the morning of September 6th dawned,

the job was complete. In less than 24 hours, much of it in darkness,

the men had laid over one half mile of railroad track, building a

spur along Lincoln Avenue from the Elberon Railroad Station in Long

Branch, New Jersey, to within one hundred yards of the Atlantic Ocean

at Francklyn Cottage. Now all the

townspeople, and the nation, could do was to await the scheduled

arrival of the visitor who was the cause of all this labor. At

exactly 1:09pm, the mortally wounded president of the United States,

James A. Garfield, arrived at the Elberon Station.

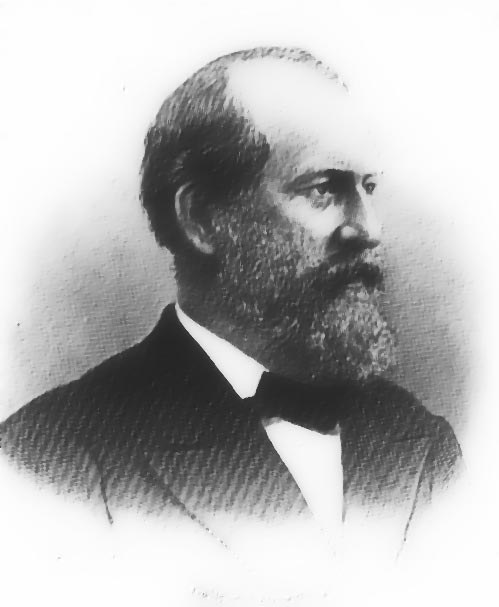

Why James A. Garfield is mostly forgotten by the nation today is a mystery. Although his term as president was short, Garfield was a true "Horatio Alger" story. He started under humble circumstances (the last president actually born in a log cabin) and made his way up the ladder of success through hard work and perseverance. He was born in 1831 in Orange Township, Ohio, the youngest of four born to Abraham and Eliza Garfield, both émigrés from New York. Abraham had come to Ohio to work as a laborer on the construction of the Ohio Canal, and after marrying Eliza purchased a small piece of land and settled down as a farmer. Abraham died in 1833, the victim of the after-effects of fighting a forest fire days earlier. Eliza was determined to keep the farm and the family together, and with the help of nearby relatives and friends she was able to do so. She encouraged the children's education, and James in particular showed an early love of knowledge and adventure.

By the age of sixteen, James was determined to become a sailor. His lack of experience doomed his hope to sail with the steamers that transversed the Great Lakes, so he signed on for three months on a canalboat on the Ohio Canal. He enjoyed the work, but a bout with malaria forced his return home. While recovering, Eliza convinced him to continue his education, so he set out for Geauga Academy in Chagrin Falls where he supported himself doing odd jobs around town. It was here that Garfield discovered another great influence in his life when he joined the Disciples of Christ Church. His enthusiasm for his new found church caused him to transfer to a new school in Hiram founded by the Disciples (now Hiram College) to continue his education. By 1852 he was teaching at the college, and preaching in the church on Sundays. It was while teaching that Garfield met his one and only love, Lucretia (Crete) Rudolph, a student of his. It was love at first sight for both of them, but they decided to be cautious and wait for Garfield to finish his education.

Garfield was determined to graduate at a more prestigious eastern school, and after saving his money he decided upon Williams College in Massachusetts. Although he did not immediately fit in with his more genteel and urbanized fellow students, he quickly won them over with his naturally friendly manner. By the end of his first year he was elected class president, and he graduated with high honors in 1856. He returned to Hiram College to teach, and within one year he had been appointed its president and married his true love, Crete.

By 1859, James Garfield had joined the new Republican Party and was elected to the Ohio Senate. He continued to teach and preach until the Civil War broke out in 1861, when the governor appointed him a lieutenant colonel. He immediately began to study tactics and the art of war, and raised his own volunteers, many from the ranks of his former students. Garfield proved to be a natural leader of men. His regiment won a victory at Middle Creek in 1862, and served with distinction at the battle at Shiloh. Garfield was promoted to Brigadier General and later became General Rosencrans' chief of staff. After being rewarded for his bravery at the Battle of Chickamauga in 1863 with another promotion, his military career was cut short. While away at war Garfield had been elected to a seat in the House of Representatives, and President Lincoln insisted he needed another vote in Congress more than he needed another general on the field. Reluctantly, Garfield resigned his commission and arrived at Washington, DC in December, 1863.

At the age of 32, Garfield had found his true calling in life, politics. He became known for his oratory skills and independence, and quickly became a leader in the House. After the war he taught himself economics and became an expert in the finances of the growing nation. He strongly supported President Ulysses S. Grant at first, but lost respect for him because of the extensive corruption of his administration. He was a friend and backer of the next president, Rutherford B. Hayes, supporting his civil service reforms, though not always his tactics. In 1880, Garfield was elected to the United States Senate by the Ohio legislature and he began to prepare for the next chapter in his life.

Before Garfield could take his seat in the Senate, he was unexpectedly nominated for President of the United States. With the Republican Convention deadlocked between President Grant (seeking a third term) and Maine senator James G. Blaine, Garfield was chosen on the 36th ballot as a compromise candidate. In the general election Garfield bested the Democratic candidate, General Winfield Scott Hancock, by a narrow margin in the popular vote.

President James A. Garfield's term in office was short, but not uneventful. He continued the civil service reform began by Hayes, and faced down his enemies in Congress, especially fellow Republicans who wanted the president to appoint political lackeys to privileged federal positions. This courageous stand against his own party earned him the respect of the American people, and his natural and friendly manner earned their endearment. Stories of how he doted on his children, playing with them and reading to them, and how he adored his Crete, made the American people feel he was one of them and not just some stuffy politician.

On the second of July, 1881, just six months into his term as president, Garfield readied himself for a well deserved "working" vacation. He had been invited to attend the commencement exercises at his Alma Mater, Williams College, and planned to take a two-week trip with stopovers in Vermont and New Hampshire to escape the heat and malaria of Washington. Crete, who had come down with the sickness earlier, was recovering at the Elberon Hotel in Long Branch, New Jersey, and planned to meet her husband in New York to accompany him on the trip. After breakfast at the White House, Garfield left for the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station with James G. Blaine, now his Secretary of State, to board an express train to New York City. As they passed through the almost empty waiting area of the station a slender man approached unseen from behind. Charles Julius Guiteau, a disappointed and unbalanced federal job seeker, drew a revolver from his pocket and fired twice. The president fell to the floor in a pool of blood.

Guiteau was quickly apprehended with little resistance. The wounded president was first brought upstairs at the station and later that day moved to the White House. The first doctor arrived quickly, and determined that the president had suffered a serious wound in the lower right back. He was followed by numerous other physicians, all of whom performed their own examinations, with many of them inserting unsterilized fingers and metal probes into the wound. It was decided that the stricken patient's liver had been punctured (probably by the doctors, not by the bullet), and he would not survive the day. Garfield remained conscious most of the time, though he was deathly pale and vomited constantly. He asked that Crete be sent for, and made sure that the news would be broken to her gently.

President Garfield confounded his doctors by living day after day, wracked by a high fever and nausea. The doctors were initially encouraged by his survival, but grew less so as his condition continued to worsen. They tried various medications and combinations of nourishment, but none seemed to help. They also continued to search for the bullet, even going so far as to have Alexander Graham Bell try his Induction Balance Machine (an early metal detector). It proved ineffective, possibly due to the metal springs in the President's bed. Why the doctors were so preoccupied with the location of the bullet is unknown. Even if they had found it, they did not believe they could have, or should have removed it. The constant search, however, worsened the situation. The doctors were also concerned with the effects of the heat might have on the patient, and the first mechanical air conditioner in the United States was designed to cool the president's room. With temperatures constantly over ninety degrees outside, the machine maintained a steady seventy-five around the sick bed.

By late July, any early enthusiasm the doctors had felt had vanished. The president was on a down hill ride of worsening blood poisoning, and they could do nothing to stem it. Although their were occasional rays of hope, the only thing now keeping the President alive was the constant care given him by round the clock medical personnel, his courageous spirit and well maintained two hundred pound frame. Although the doctors were pessimistic, they did not share their misgivings with the public. Instead, they issued optimistic reports on the "improvement" of the president's health throughout the ordeal. The nation followed the sad story on a daily basis and prayed for his recovery. Already beloved by the public, Garfield further endeared them with his brave battle for recovery. Thinking only of his family and nation, he constantly assured both that he felt better than he appeared and was getting stronger, even though he was surely aware of his true situation.

By the first week of September the president wanted to leave the White House and travel home to Ohio. The doctors, perhaps believing that no one should be subject to dying in the swamps of Washington, agreed, but felt Ohio was too far to travel. At the suggestion of Crete, Long Branch was substituted and arrangements were immediately made. Garfield, perhaps sensing the end was near, grew impatient as the plans for his removal took longer than expected. He admonished his staff, saying, "No, no, I don't want any more delay!" Finally, on September 6th at 6:00am, the president departed the White House bound for the Jersey Shore on a special train provided by the Pennsylvania Railroad.

CLICK HERE TO CONTINUE TO PART II AS PRESIDENT GARFIELD ARRIVES AT LONG BRANCH