THE DYING DUTCHMAN

Click On Anything In Color To View Photo Or Image

It was a normal Wednesday evening on October 23, 1935, at the Palace Chop House and Tavern in Newark, New Jersey, when a group of four well dressed men made their way past the crowded bar to a secluded dining and private dining room in the back. After ordering drinks and dinner, the men began talking business. They continued their discussion through dinner. At 9:00pm a young and attractive woman stopped to drop off some paperwork, staying for at least one drink. By 10:00pm she had left. The bar and restaurant were empty except for the four diners, a couple swinging around the dance floor upstairs, the bartender and a few employees in the kitchen cleaning up. A man entered the bar brandishing a pistol and ordered the bartender to the floor. He complied so quickly, he never even saw the second man, armed with a shotgun, enter. The two men made their way to the dining room in the back, and opened fire. Three men were quickly down and wounded. They found the fourth, the intended "hit", in the bathroom. He never had a chance. Arthur Flegenheimer, alias Dutch Schultz, and his three associates were mortally wounded. The "Dutchman" was dying.

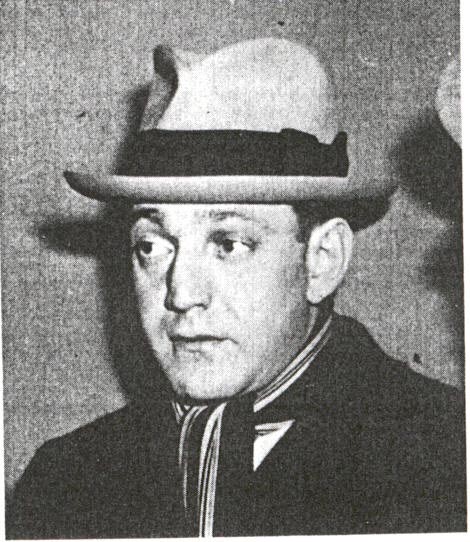

Dutch Schultz had a long and varied criminal history. He was probably the most well known criminal of his time, and was once declared Public Enemy #1 by the FBI. Famous for his ruthlessness, violence and temper, he worked his way up the criminal ladder in the mean streets of the Bronx from an early age. Born in 1902, Schultz began with some petty thefts and assaults, and by the age of 17, had graduated to more serious crimes. He was convicted of robbery in 1919, and sent to a juvenile penitentiary. After a failed escape attempt, he was released after serving 15 months. Despite numerous indictments and arrests, he never again served time behind bars. Following his release, he quickly resumed his former occupation, and first began using the name "Dutch Schultz", appropriated from a legendary deceased New York gang member.

By 1925, Schultz had become both criminally successful, and politically connected. He used money and violence to gain control over unions and the "Numbers Racket", or "Policy Racket", an early and illegal version of the lottery. From his stronghold in the Bronx, his empire spread rapidly into Harlem and parts of Manhattan. He soon discovered "Bootlegging", the importation of liquor, then prohibited by the 18th Amendment (Prohibition), which proved to be a lucrative addition to his already profitable enterprises. His most serious rival at this time was Vincent (Mad Dog) Coll, a former associate who matched Schultz in both temperament and talent. Their fight, bloody and long, lasted for years, claiming many lives. At one point Schultz was so incensed with Coll, he went to a police station and offered a new house to any officer who would gun him down. His generous offer went unclaimed. The war ended in 1932, when Coll was killed by three of Shultz's gunmen while using a phone booth in a Manhattan drug store.

The end of Prohibition in 1933 did not slow Schultz down. He tightened his control over his unions and numbers racket, and continued to increase his influence at Tammany Hall, the seat of power of the corrupt Democratic Machine which controlled the courts, police and just about everything else in New York City. With the help of his new found friends, raids and arrests became a thing of the past, and Schultz was free to further expand and consolidate his power. Finally, the Federal Government felt it had to step in when the local authorities refused to prosecute him. Schultz was indicted in 1933 for tax evasion, but it did not interfere with business. The New York City police refused to pursue him, and he remained at large for almost two years. When J. Edgar Hoover, Director of the FBI, named him "Public Enemy #1", Schultz surrendered, possibly mindful of the fate of the previous "Public Enemy #1", John Dillinger.

Dutch Schultz's tax evasion trial began in early 1934 in Syracuse, New York, after his lawyers, who included a former U.S. Prosecutor and a former New Jersey Governor, successfully argued that he could not receive a fair trail in New York City. Schultz's defense was simple but effective. After the federal government had brought down Al Capone and his brother with the newly created charge of tax evasion, Schultz could see the handwriting on the wall and had tried to settle his debt with the government. He even went so far as to send his lawyers to the Internal Revenue Service in Washington D.C. with $100,000 in cash as a settlement offer. The IRS refused, claiming he owed much more. However, Schultz could now claim he had tried to pay his taxes like any other law abiding citizen, but the government refused to accept the money. Amazingly, this defense (along with some alleged jury tampering) worked with seven out of the twelve jurors, and a mistrial was declared. A new trial was scheduled later that year in Malone, New York, the hometown of the presiding judge on the northern edges of Adirondack Mountains. It was here that Schultz showed the "street smarts" which had kept him free and alive for so long. He and a group of his more honest looking associates arrived weeks before the trial date, and attempted to gain influence with the potential jury pool. They bought dinner and drinks wherever they went, gave interviews with the local papers, and Schultz even attended a local baseball game as the personal guest of the mayor. By the time the trial started, Schultz had convinced many people in the town that he was really a "good guy" being persecuted by a vengeful government. The presiding judge was not amused by this pretrial generosity, and he revoked Schultz's bail. However, the damage was already done and the jury found him not guilty a week later.

Although the Dutchman had beaten the rap, the end was near. There were many other pending indictments, and his business had already suffered from his absence. Other leading New York mobsters including Lucky Lucianao and Albert Anastasia moved in on his rackets, and his legal problems continued to keep Schultz out of town. He set up shop in nearby Newark, New Jersey in August, 1935, and moved into the Robert Treat Hotel. Almost every evening he and his three closest associates, Bernard (Lulu) Rosenkrantz, his second in command, Otto (Abbadabba) Berman and Abe (Misfit) Landau (AKA Abe Frank), would meet at the Palace Chop House around the corner on Park Street. There they would talk business and go over the day's receipts. They kept a regular routine, which made them easy prey on that fateful October evening.

The most amazing aspect of the shooting was not the "hit" itself, but its aftermath. With all the bullets and shells that flew, no one was immediately killed. Schultz stumbled out of the bathroom and asked the bartender to call an ambulance. Rosenkrantz, despite being shot seven times, actually asked for change of a dime to use the phone booth to call the police and report the shooting. Berman was still breathing though unconscious. The final victim and the first to die, Landau, raced after the gunmen firing his pistol, causing a shootout outside on the sidewalk. He died there after collapsing from his wounds. The police arrived to find three wounded men amid the bloody carnage, with the two conscious ones, Schultz and Rosenkrantz refusing to answer any of their questions. They were all taken to Newark City Hospital on Fairmount Avenue. As Schultz was wheeled into the hospital on a stretcher a photographer blocked his way. He growled, "Say, which is more important, your picture or my life? Scram!" He then gave an intern the $725.00 in cash he was carrying on him to ensure good treatment. The intern turned it over to the hospital supervisor. When the police queried Rosenkrantz, he continued to refuse to answer any of their questions, and repeatedly demanded an ice cream soda. At 3:00am Berman was the second to die, never having regained consciousness.

Dutch Schultz, although fatally wounded in the abdomen, lasted until 8:30 that Thursday evening. The wound caused massive internal bleeding and an infection, and when lucid he continued to refuse to say who shot him or why. His relatives and friends, including his wife and mother visited him at the hospital throughout the day. As his condition worsened and his fever increased, he began to drift in and out of consciousness, often babbling strange and disconnected phrases such as, "The glove will fit what I say," and "The sidewalk was in trouble, and the bears were in trouble." The authorities kept a stenographer at Schultz's bedside to record every last rambling thought he uttered. Federal agents and police from New York and New Jersey tried in vain to analyze his last words after his death. Although some of Schultz's rantings may have referred to his shooting and criminal activities, most were believed to be about childhood memories, old rhymes and songs, etc. The stenographer's transcript was immortalized in various books and stories, and forms the basis of William Burrough's well known story, "The Last Words of Dutch Schultz." With Schultz dead, only Rosencrantz was left alive. He lasted until 3:20 the following morning, defiant and silent to the end. Schultz body was removed later that day to Hawthorne, New York for burial. The only rememberence of Dutch Schultz remaining in Newark is a makeshift memorial inscribed into the cement used to fill in one of the side windows of the Palace Chop House today.

As for the killers, when the get-away car pulled away from the Palace Chop House following the shootings, it left one of the killers stranded. He fled on foot in the direction of the car, turned left on Pine Street, and probably headed to nearby James Street, where the car was later found abandoned by the police with one of weapons used in the shootings inside. Although the police investigated the few clues they had, they were unable to identify the killers and moved on to other cases. The press at the time seemed more concerned about why one of Schultz's men was carrying an Essex County Sheriff's Badge, then the death of four men. Local authorities were more concerned with punishing the Palace Chop House and Robert Treat Hotel for allowing criminals to congregate at their establishments. Five years after Schultz's death, in the course of another investigation, a convicted criminal identified Mendy Weiss and Charlie (the Bug) Workman as the shooters, with Workman as the killer of Schultz. The driver of the get-away car, known only as a kid from a Jersey City gang was never identified. Workman was tried and convicted in Newark, and sentenced to life in prison. Weiss was executed in New York for an unrelated murder before he could face trial.

Who ordered the killing of Dutch Schultz? It was probably Lucky

Luciano and the other mobsters who made up the "Syndicate"

that controlled organized crime in New York and elsewhere. Schultz

had wanted Thomas E. Dewey, the mob-busting

New York prosecutor and his personal nemesis, killed and even

threatened to do the job himself. The Syndicate, fearing bad

publicity and an intense crackdown on their operations, could not

allow that to happen. Unable to buy Dewey off, they were forced to

order Schultz killed to prevent him from carrying out his threat. Of

course, with Schultz dead, Dewey needed a new number one target, and

Luciano was it. Six months after Schultz's murder, Luciano was

indicted on 62 charges with a maximum of 1,950 years. He was

convicted in June, 1936. As he was taken to prison to begin serving

his 30 to 50 year sentence, I wonder if Luciano thought maybe Dutch

had the right idea after all.

SOURCES

BOOKS:

The Heydays of the Adirondacks

By: Maitland C. Desormo

Adirondack Yesteryears, 1974 ---- BUY

THIS BOOK

Jerseyana: The Underside of New Jersey History

By: Marc Mappen

Rutgers University Press, 1994 ---- BUY

THIS BOOK

Kill the Dutchman! The Story of Dutch Schultz

By: Paul Sann

Arlington House, 1971 ---- BUY

THIS BOOK

The Last Words of Dutch Schultz

By: William S. Burroughs

Viking Press, 1969 ---- BUY

THIS BOOK

NEWSPAPERS:

The New York Times

New York, NY

The New York Daily News

New York, NY

The Newark Star-Eagle

Newark, NJ

Want to read the complete transcript of Dutch Schultz's last words?

Go to: Dutch

Schultz on His Deathbed