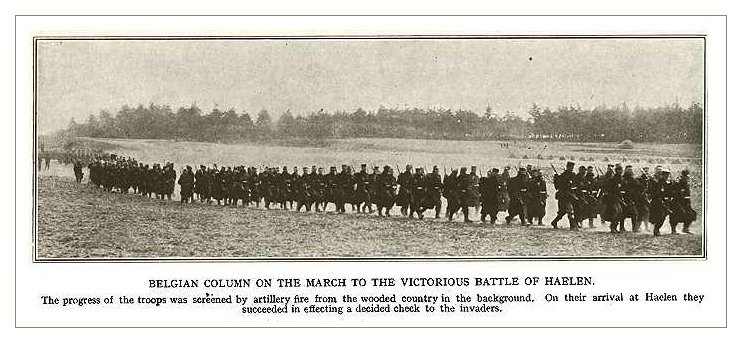

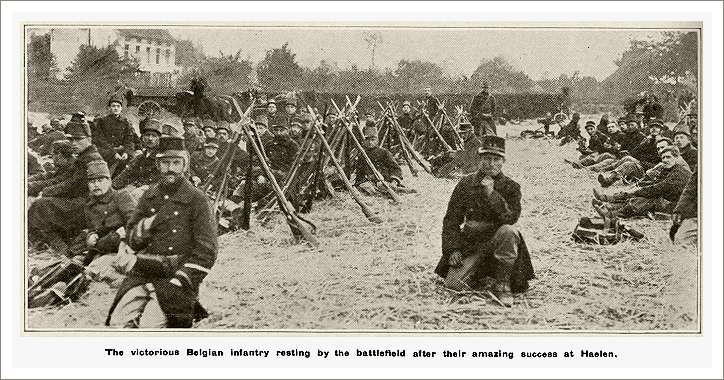

the First Belgian Victory of the War

from the triptych 'The Battle of Haelen' by French artist Alphonse Lalauze

Brussels, August 16, 1914.-This morning I walked out of my office and bumped into Frederick Palmer. I had no idea he was so near. Two weeks ago he was in Vera Cruz, but made a bee-line for Brussels at the first news of impending war. In the breathing spaces during the morning I got in a little visiting with him. He stayed to lunch at the Legation and so did I. In the afternoon I took him to the Foreign Office and the War Office and the Gendarmerie, and got him outfitted with passes, so that he can make a try to get towards the front. As a measure of precaution I added another laisser-passer to my collection, with a beautiful photograph on it. The collection grows every day.

I went to the Palace to dine with Palmer and Blount. We had hardly got seated when in walked Richard Harding Davis (see excerpt from his book 'With the Allies') and Gerald Morgan and joined us. I had not expected Davis here so soon, but here he is.

He was immaculate in dinner jacket and white linen, for war does not interfere with his dressing. While we were dressing, a lot of motors came by filled with British officers. There was a big crowd in the square, and they went crazy with enthusiasm, cheering until the windows rattled.

Brussels, August 18, 1914. At ten in the morning I started with Frederick Palmer and Blount in the latter's car, to see whether we could get a little way out of town and get a glimpse of what was going on. We were provided with laisser-passers and passports and all sorts of credentials, but as a strict prohibition against sightseers has been enforced for some days, we rather doubted whether we should be able to get farther than the edge of town. Before we got back we had gone more than a hundred kilometres through the heart of things and seen a great deal more than anybody should be allowed to see. We got back to town about eight o'clock, thoroughly tired and with eyes filled with dust and cinders.

Part way along the avenue we were hailed by a soldier, who asked us for a lift as far as Tervueren. He climbed into the car beside me and rode out. The Forest de Soignes was mournful. Quatre Bras, where the cafés are usually filled with a good-sized crowd of bourgeois, was deserted and empty. The shutters were up and the proprietors evidently gone. The Minister's house, near by, was closed. The gate was locked and the gardener's dog was the only living thing in sight. We passed our Golf Club a little farther on toward Tervueren. The old chateau is closed, the garden is growing rank, and the rose-bushes that were kept so scrupulously plucked and trim were heavy with dead roses. The grass was high on the lawns; weeds were springing up on the fine tennis courts. The gardeners and other servants have all been called to the colours. Most of the members are also at the front, shoulder to shoulder with the servants. A few caddies were sitting mournfully on the grass and greeted us solemnly and without enthusiasm. These deserted places are in some ways more dreadful than the real horrors at the front. At least there is life and activity at the front.

Before we got out of town the guards began stopping us, and we were held up every few minutes until we got back to town at night. Sometimes the posts were a kilometre or even two kilometres apart. Sometimes we were held up every fifty yards. Sometimes the posts were regulars, sometimes Gardes Civiques; often hastily assembled civilians, mostly too old or too young for more active service. They had no uniforms, but only rifles, caps, and brassards to distinguish them as men in authority. In some places the men formed a solid rank across the road. In others they sat by the roadside and came out only when we hove in sight. Our laisser-passers were carefully examined each time we were stopped, even by many of the guards who did not understand a word of French, and strangely enough, our papers were made out in only the one language. They could, at least, under-stand our photographs and took the rest for granted.

When we got to the first out post at Tervueren, the guard waived our papers aside and demanded the password. Then our soldier passenger leaned across in front of Blount and whispered "Belgique." That got us through everything until midday, when the word changed.

From Tervueren on we began to realise that there was really a war in progress. All was preparation. We passed long trains of motor trucks carrying provisions to the front. Supply depots were planted along the way. Officers dashed by in motors. Small detachments of cavalry, infantry, and artillery pounded along the road toward Louvain. A little way out we passed a company of scouts on bicycles. They are doing good work and have kept wonderfully fresh. In this part of the country everybody looked tense and anxious and hurried. Nearer the front they were more calm.

Most of the groups we passed mistook our flag for a British standard and cheered with a good will. Once in a while somebody who recognised the flag would give it a cheer on its own account, and we got a smile everywhere.

All the farmhouses along the road were either already abandoned or prepared for instant flight. In some places the reaping had already begun, only to be abandoned. In others the crop stood ripe, waiting for the reapers that may never come. The sight of these poor peasants fleeing like hunted beasts, and their empty houses or their rotting crops was the worst part of the day. It is a shame that those responsible for all this misery cannot be made to pay the penalty - and they never can, no matter what is done to them.

Louvain is the headquarters of the King and his Etat-Major. The King is Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces operating in Belgium, and is apparently proving to be very much of a soldier. The town is completely occupied and troops line the streets, stop- ping all motors and inspecting papers, then telling you which way you can go. We were the only civilians on the road all day, except the Red Cross people. The big square was completely barred off from general traffic and was surrounded with grenadiers. We got through the town and stopped at the only café we could find open, where we had a bottle of mineral water and talked over what we should do next.

In Louvain there is an American theological seminary. We had had some correspondence with Monseigneur de Becker, its Rector, as to what he should do to protect the institution. At our suggestion he had established a Red Cross hospital and had hoisted a big American flag, but still he was not altogether easy in his mind. I called on him and did my level best to reassure him, on the ground that the Germans were certainly not making war on seminaries or priests, and that if the Germans reached Louvain, all he had to do was to stay peacefully at home and wait for quiet to be restored. Most of his students were gone and some of the faculty had followed them, so his chief concern was for the library and other treasures. My arguments did not seem to have very much weight, but I left with a promise to look in again at the first opportunity and to respond to any call the Rector might make.

From the seminary we drove along the Tirlemont road, to see if we could get to that little town and see some of the fighting that was known to be going on. At the edge of the town we came to a barricade of carts, road-rollers, and cobble stones, where we were courteously but firmly turned back. Everybody was anxious to make it as nice as possible for us, and one of the bright boys was brought forward to tell us in English, so as to be more convincing. He smiled deprecatingly, and said: "Verrreh bad. Verrreh sorreh. Oui mus' mak our office, not?" So we turned and went back to town. They had told us that nobody could go beyond the barricade without an order from the Commandant de Place at Louvain.

On the way back we decided that we could at least try, so we hunted through the town until we found the headquarters of the Commandant. A fierce-looking sergeant was sitting at a table near the door, hearing requests for visas on laisser-passers. Everybody was begging for a visa on one pretext or another, and most of them were being turned down. I decided to try a play of confidence, so took our three cards and walked up to his table, as though there could be no possible doubt of his doing what I wanted. I threw our three laisser-passers down in front of him, and said in a businesslike tone, "Trois visés pour Tirlemont, s'il vous plait." My man looked up in mild surprise, viséd the three papers without a word, and handed them back in less time than it takes to tell it. We sailed back to the barricade in high feather, astonished the guard with our visa, and ploughed along the road, weaving in and out among ammunition wagons, artillery caissons, infantry, cavalry, bicyclists - all in a dense cloud of dust. Troops were everywhere in small numbers. Machine guns, covered with shrubbery, were thick on the road and in the woods. There was a decidedly hectic movement toward the front, and it was being carried out at high speed without confusion or disorder. It was a sight to remember. All along the road we were cheered both as Americans and in the belief that we were British. Whenever we were stopped at a barricade to have our papers examined, the soldiers crowded around the ear and asked for news from other parts of the field, and everybody was wild for newspapers. Unfortunately we had only a couple that had been left in the car by accident in the morning. If we had only thought a little, we could have taken out a cartful of papers and given pleasure to hundreds.

The barricades were more numerous as we drew nearer the town. About two miles out we were stopped dead. Fighting was going on just ahead, between us and the town, and the order had been given out that nobody should pass. That applied to military and civilians alike, so we could not complain, and came back to Louvain, rejoicing that we had been able to get so far.

We hunted up our little café and ate our sandwiches at a table on the sidewalk, letting the house profit to the extent of three glasses of beer. We were hardly seated when a hush fell on the people sitting near. The proprietor was summoned and a whispered conversation ensued between him and a bewhiskered old man three tables away. Then Mr. Proprietor sauntered over our way with the exaggerated carelessness of a stage detective. He stood near us for a minute or two, apparently very much interested in nothing at ail. Then he went back, reported to Whiskers, and the buzz of conversation began again as though nothing had happened. After a bit the proprietor came over again, welcomed us to the city, asked us a lot of questions about ourselves, and finally confided to us that we had been pointed out as Germans and that he had listened to us carefully and discovered that we were nothing of the sort. "J'ai tres bonne oreille pour les langues," he said.

Of course we were greatly surprised to learn that we had been under observation. Think of German spies within 200 yards of the headquarters of the General Staff ! (And yet they have caught them that near.) Every active citizen now considers himself a policeman on special duty to catch spies, and lots of people suffer from it. I was just as glad the proprietor had not denounced us as spies, as the populace has a quite understandable distaste for them. I was glad the bright café proprietor could distinguish our lingo from German.

After lunch we went down to the headquarters of the General Staff, to see if we needed any more visas. We did not, but we got a sight of the headquarters with officers in all sorts of uniforms coming and going.

The square was full of staff autos. The beautiful carved Hotel de Ville is the headquarters. As we walked by, a British major-general came down the steps, returned everybody's salutes, and rolled away-a fine gaunt old type with white hair and moustache - the sort you read about in story-books.

After lunch we found that there was no use in trying to get to Tirlemont, so gave that up, and inquired about the road to Diest. Everybody who was in any sort of position to know told us we could not get more than a few kilometres along the road, and that as Uhlans were prowling in that neighbourhood, we might be potted at from the woods or even carried off. On the strength of that we decided to try that road, feeling fairly confident that the worst that could happen to us would be to be turned back.

As we drew out along the road, the traffic got steadily heavier. Motors of all sorts- beautifully finished limousines filled with boxes of ammunition or sacks of food, carriages piled high with raw meat and eases of biscuit. Even dog-carts in large numbers, with the good Belgian dogs straining away at the traces with a good will, and barking with excitement. They seemed to have the fever and enthusiasm of the men and every one was pulling with all his strength. In some places we saw men pushing heavily-laden wheelbarrows, with one or two dogs pulling in front.

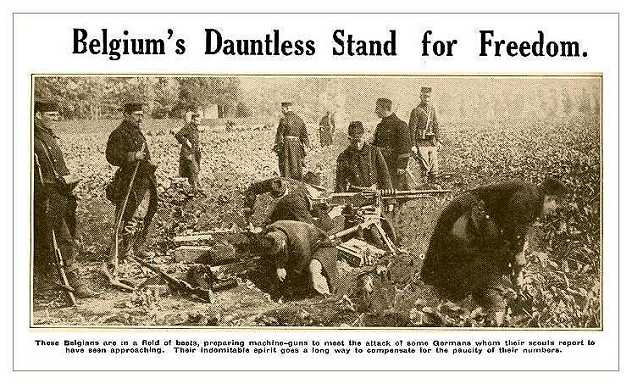

From Louvain on most of the barricades were mined. We could see clearly as we passed where the mines were planted. The battery jars were under the shelter of the barricade and the wire disappeared into some neighbouring wood or field. Earthworks were planted in the fields all along the lines, good, effective, well-concealed entrenchments that would give lots of trouble to an attacking force. There was one place where an important entrenchment was placed in a field of hay. The breastworks were carefully covered with hay and the men had it tied around their hats in such a way as to conceal them almost completely. This war is evidently going to be fought with some attention to detail, and with resourcefulness.

Diest itself we reached at about half past three, after having been nearly turned back six or seven times. We were the only civilians that had turned up all day, and although our papers seemed to be all right and we could give a good account of ourselves, our mere presence was considered so remarkable that a good many of the outposts were inclined to turn us back. By virtue of our good arguments and our equally good looks, however, we did manage to get through to the town itself.

Diest is an old town which figures a good deal in the combats of the Middle Ages. It has a fine old church, quite large, a good hotel de ville, and clean, Dutch-looking streets, with canals here and there. The whole town is surrounded with high earthworks, which constituted the fortifications which were part of the line of forts erected by the allies after Waterloo, as a line of defence against French aggression. These forts were so numerous that Belgium in her younger days had not sufficient men to garrison them. A number of them were abandoned, finally leaving Antwerp, Liége, and Namur to bear the burden. Brialmont, who built the great ring forts at Liége, wanted to build modern fortifications at Diest, but could not get those holding the purse-strings to see things his way.

Diest was attacked by Germans about three days ago. They wanted to take the old fortifications so as to control the road and use the area as a base of operations. It could hardly be called a big battle, but was more probably in the nature of a reconnaissance in force with four or five regiments of cavalry. This part of Belgium is the only place on the whole field of operations where cavalry can be used, and they are certainly using it with a liberal hand, probably in an attempt to feel out the country and locate the main body of opposing troops. They have got into a lot of trouble so far, and I am sure they have not yet located the main bodies of the allied armies.

The shops were all closed and most of the people were sitting on the sidewalk waiting for something to turn up. Some of them had evidently been to America, and we had an ovation all the way in. The Grande Place was filled with motors and motor trucks, this evidently being a supply depot. We had some of the local mineral water and talked with the people who gathered round for a look at the Angliches.

They were all ready for anything that might come, particularly Prussians. In the old days the Uhlans spread terror wherever they appeared, to burn and shoot and plunder. Now they seem to arouse only rage and a determination to fight to the last breath. There was a little popping to the north and a general scurry to find out what was up. We jumped into the car and made good time through the crowded, crooked little streets to the fortifications. We were too late, however, to see the real row. Some Uhians had strayed right up to the edge of town and had been surprised by a few men on the earthworks. There were no fatalities, but two wounded Germans were brought into town in a motor. They were picked up without loss of time and transported to the nearest Red Cross hospital.

Cursing our luck we started off to Haelen for a look at the battlefields. Prussian cavalry made an attack there the same day they attacked Diest, and their losses were pretty bad.

At one of the barricades we found people with Prussian lances, caps, haversacks, etc., which they were perfectly willing to sell. Palmer was equally keen to buy, and he looked over the junk offered, while some two hundred soldiers gathered around to help and criticise. I urged Palmer to refrain, in the hope of finding some things ourselves on the battlefield. He scoffed at the idea, however. He is, of course, an old veteran among the war correspondents, and knew what he was about. He said he had let slip any number of opportunities to get good things, in the hope of finding something himself, but there was nothing doing when he got to the field. We bowed to his superior knowledge and experience, and let him hand over an English sovereign for a long Prussian lance. I decided to do my buying on the way home if I could find nothing myself.

The forward movement of troops seemed to be headed toward Diest, for our road was much more free from traffic. We got into Haelen in short order and spent a most interesting half-hour talking to the officer in command of the village. As we came through the village we saw the effect of rifle fire and the work of machine guns on the walls of the houses. Some of them had been hit in the upper storey with shrapnel and were pretty badly battered up. The village must have been quite unpleasant as a place of residence while the row was on. The commanding officer, a major, seemed glad to find someone to talk to, and we stretched our legs for half an hour or so in front of his headquarters and let him tell us all about what had happened. He was tense with rage against the Germans, whom he accused of all sorts of barbarous practices, and whom he announced the Allies must sweep from the earth. He told us that only a few hours before a couple of Uhlans had appeared in a field a few hundred yards from where we were standing, had fired on two peasant women working there, and then galloped off. Everywhere we went we heard stories of peaceful peasants being fired on. It seems hard to believe, but the stories are terribly persistent. There may be some sniping by the non-combatant population, but the authorities are doing everything they can to prevent it, by requiring them to give up their arms and pointing out the danger of reprisals.

Before we moved on, our officer presented me with a Prussian lance he had picked up on the battlefield near Haelen. We got careful directions from him for finding the battlefield and set off for Loxbergen, where the fight had taken place the day before. The run was about four kilometres through little farms, where the houses had been set on fire by shrapnel and were still burning. The poor peasants were wandering around in the ruins, trying to save odds and ends from the wreck, but there was practically nothing left. Of course they had had to flee for their lives when the houses were shelled, and pretty much everything was burned before they could safely venture back to their homes.

We had no difficulty in locating the field of battle when we reached it. The ground was strewn with lances and arms of all sorts, haversacks, saddle-bags, trumpets, helmets and other things that had been left on the ground after the battle. There were a few villagers prowling around, picking things up, but there were enough for everybody, so we got out and gathered about fifteen Prussian lances, some helmets, and other odds and ends that would serve as souvenirs for our friends in Brussels. As everybody took us for English, they were inclined to be very friendly, and we were given several choice trophies to bring back. While we were on the field, a German aeroplane came soaring down close to us and startled us with the sharp crackling of its motor. It took a good look at us and then went its way. A little farther along, some Belgian troops fired at the aeroplane, but evidently went wide of their mark, for it went unconcernedly homeward. We wandered through the ruins of some old farms and sized up pretty well what must have happened. The Germans had evidently come up from the south and occupied some of the farmhouses along the road. The Belgians had come down from the north and opened fire on the houses with rapid-fire guns, for the walls were riddled with small holes and chipped with rifle fire.

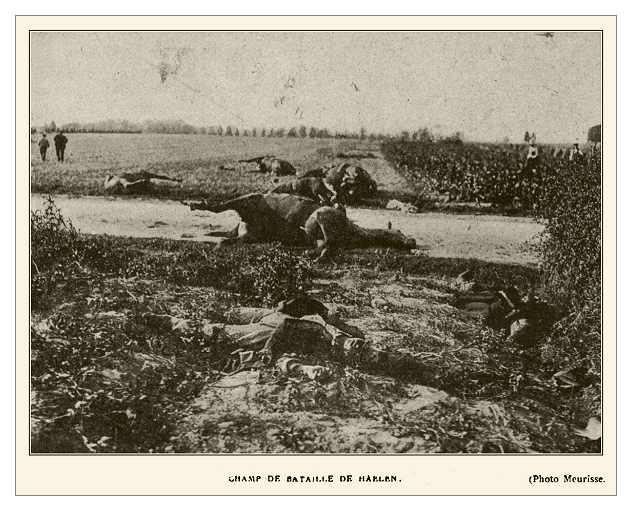

Then shrapnel had been brought into play, to set the houses on fire and bring the German troops out into the open. Then they had charged the Belgians across an open field and apparently with disastrous results. Part of the ground was in hay which had already been harvested and piled in stacks, the rest was in sugar beets. The Prussians had charged across the field and had come upon a sunken road into which they fell helter-skelter without having time to draw rein. We could see where the horses had fallen, how they had scrambled to their feet and tried with might and main to paw their way up on the other side. The whole bank was pawed down, and the marks of hoofs were everywhere. The road was filled with lances and saddles, etc. All through the field were new-made graves. There was, of course, no time for careful burial. A shallow trench was dug every little way-a trench about thirty feet long and ten feet wide. Into this were dumped indiscriminately Germans and Belgians and horses, and the earth hastily thrown over them - just enough to cover them before the summer sun got in its work.

There were evidences of haste; in one place we saw the arm of a German sergeant projecting from the ground. It is said that over three thousand men were killed in this engagement, but from the number of graves we saw I am convinced that this was a good deal overstated. At any rate it was terrible enough; and when we think that this was a relatively unimportant engagement, we can form some idea of what is going to happen when the big encounter comes, as it will in the course of a few days more. It is clear that the Germans were driven off with considerable losses, and that the Belgians still hold undisputed control of the neighbourhood. There were a few scattered Uhlans reconnoitring near by, but they were not in sufficient numbers to dare to attack.

After gathering our trophies we were ready to start for home; and it was well we should, for it was getting rather late in the afternoon and we had a long trip ahead of us with many delays.

Soon after leaving Haelen, on our way back we met a corps of bicycle carabiniers who were rolling along toward Haelen at top speed. The officer in command held us up and asked us for news of the country we had covered. He seemed surprised that we had not seen any German forces, for he said the alarm had been sent in from Haelen and that there were strong forces of Belgians on the way to occupy the town and be ready for the attack. When he had left us, we ran into one detachment after another of infantry and lancers coming up to occupy the little village.

When we got to the barricade at the entrance to Diest, the soldiers of the guard poured out and began taking our trophies out of the ear. We protested vigorously, but not one of them could talk anything but Walloon - and French was of no use. Finally, a corporal was resurrected from somewhere and came forth with a few words of French concealed about his person. We used our best arguments with him, and he finally agreed to let a soldier accompany us to the town hall and see what would be done with us there. The little chunky Walloon who had held us up at the barrier climbed in with great joy, and away we sped. The little chap was about the size and shape of an egg with whopping boots, and armed to the teeth. He had never been in a car before, and was as delighted as a child. By carefully piecing words together through their resemblance to German, we managed to have quite a conversation; and by the time we got to the Grande Place we were comrades in arms. I fed him on cigars and chocolate, and he was ready to plead our cause. As we came through the streets of the town, people began to spot what was in the car and cheers were raised all along the line. When we got to the H6tel de Ville, the troops had to come out to keep back the curious crowd, while we went in to inquire of the officer in command as to whether we could keep our souvenirs. He was a major, a very courteous and patient man, who explained that he had the strictest orders not to let anything of the sort be carried away to Brussels. We bowed gracefully to the inevitable, and placed our relics on a huge pile in front of the Hotel de Ville. Evidently many others had met the same fate, for the pile contained enough trophies to equip a regiment. The major and an old fighting priest came out and commiserated with us on our hard luck, but their commiseration was not strong enough to cause them to depart from their instructions.

The major told us that they had in the Hotel de Ville the regimental standard of the Death's Head Hussars. They are keeping it there, although it would probably be a great deal safer in Brussels.

Unfortunately the room was locked, and the officer who had the key had gone, so we could not look upon it with our own eyes.

Heading out of town, a young infantryman held us up and asked for a lift. He turned out to be the son of the President of the Court of Appeal at Charleroi. He was a delicate- looking chap with lots of nerve but little strength. His heavy infantry boots looked oubly heavy on him, and he was evidently in a bad way from fatigue. He had to rejoin his regiment which was twelve miles along the road from Diest, o we were able to give him quite a boost. He asked me to get word to his father that he wanted to be given a place as chauffeur or aviator, and in any other place that would not require so much foot work. There must be a lot of this sort. We finally landed him in the bosom of his company and waved him a good-bye. By this time it was twilight, and the precautions of the guards were redoubled. A short way out from Louvain, a little Walloon stepped out from behind a tree about a hundred yards in front of us and barred the way excitedly. We were going pretty fast and had to put on emergency brakes, and skid up to him with a great smell of sizzling rubber. He informed us that papers were no good any more; that we must know the password, or go back to Louvain for the night. This he communicated to us in his best Walloon, which we finally understood.

Blount started to tell him that we did not know, as the word had been changed since we left; but in one of my rare bursts of resourcefulness I thought to try a ruse, so leaned forward very confidentially and gave him the password for the morning-" Belgique." With a triumphant look, he shook his head and countered: "No, Haelen!" He had shown the travellers from the outside world that he knew more than they did, and he was without any misgivings as to what he had done, and let us proceed without further loss of time. We got all the way back to Tervueren with this password, which was all that saved us from spending the night in Louvain and getting back nobody knows when. Nearly opposite the Golf Club we were stopped with the tidings that the word was no longer good, but that if we had satisfactory papers we could get into town. For some reason the password had evidently been changed since we left Louvain, so we got through with rare luck all along the line.

We rolled up to the Legation a few minutes before eight o'clock, and found that there was a great deal of anxiety about us. Cheerful people had been spreading the news all day that if we fell into the hands of the Germans they would hold us as hostages, as they did the Bishop and Mayor of Liége. They probably would if they had caught us, but they did not catch us.

Palmer was pleased at the amount we saw. It was by rare good luck that we got through the lines, and we were probably the last who will get so far. To-day all laisser- passers have been cancelled, and nobody can set foot out of town to the east. It gave us a pretty good idea before we got through as to how the troops must be disposed. I came within an ace of putting off our trip for a day or two. If I had, it would have cut me out of seeing anything.

As usual when I go out, the lid had blown off the Legation and the place was in a turmoil. During the afternoon the Government had decided to move to Antwerp and take refuge in the enceinte. The Queen, the Royal children, and some of the members of the Government left at eight o'clock, and this morning more of them left. Most of the Diplomatic Corps have gone, and will have so much time to think of their troubles that they will be more uncomfortable than we are. The Spanish Minister will stay on and give us moral support.

corpses on the battlefield at Haelen

burial of horses afterwards