- from the book

- 'A Diplomatic Diary'

- by Hugh Gibson 1917

Mr. Gibson was Secretary to the American Legation in Brussels in 1914 to 1917, While making a diplomatic trip to Antwerp from Brussels (then already occupied by the Germans) , he passed through the front lines. In Antwerp, he was present during the first Zeppelin bombing raid. Here is his description of the events :

August 25, 1914 : We brought van der Bist back to the hotel, and with his influence ran our car into the Gendarmerie next door. Then to bed.

Blount and I had a huge room on the third floor front. We had just got into bed and were settling down to a good night's rest when there was an explosion, the like of which I have never heard before, and we sat up and paid strict attention. We were greatly interested, but took it calmly, knowing that the forts were nearly four miles out of town and that they could bang away as long as they liked without doing more than spoil our night's sleep. There were eight of these explosions at short intervals, and then as they stopped there was a sharp purr like the distant rattle of a machine gun. As that died down, the chimes of the Cathedral - the sweetest carillon I have ever heard - sounded one o'clock. We thought that the Germans must have tried an advance under cover of a bombardment, and retired as soon as they saw that the forts were vigilant and not to be taken by surprise. We did not even get out of bed. About five minutes later we heard footsteps on the roof and the voice of a woman in a window across the street, asking someone on the sidewalk below whether it was safe to go back to bed. I got out and took a look into the street. There were a lot of people there talking and gesticulating, but nothing of enough interest to keep two tired men from their night's sleep, so we climbed back into bed and stayed until morning.

Blount called me at what seemed an unreasonably early hour and said we should be up and about our day's work. When we were both dressed, we found that we had made a bad guess, when he looked at his watch and discovered that it was only a quarter to seven. Being up, however, we decided to go down and get our breakfast.

When we got down we found everybody else stirring, and it took us several minutes to get it through our heads that we had been through more excitement than we wotted of. Those distant explosions that we had taken so calmly were bombs dropped from a Zeppelin which had sailed over the city and dropped death and destruction in its path. The first bomb fell less than two hundred yards of where we slept - no wonder that we were rocked in our beds! After a little breakfast we sallied forth.

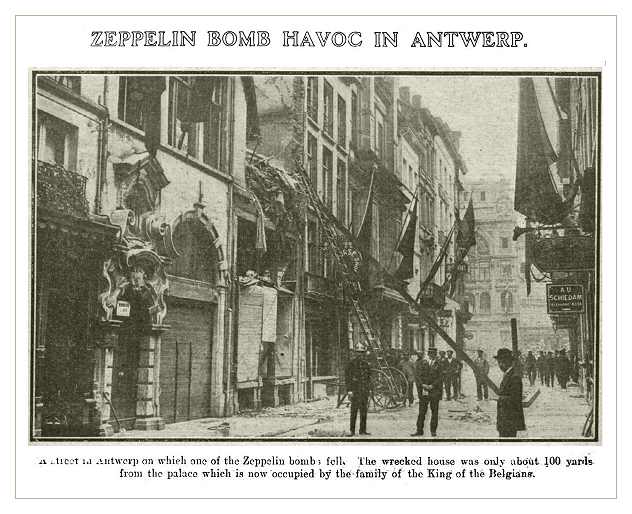

The first bomb was in a little street around the corner from the hotel, and had fallen into a narrow four-storey house, which had been blown into bits. When the bomb burst, it not only tore a fine hole in the immediate vicinity, but hurled its pieces several hundred yards. All the windows for at least two hundred or three hundred feet were smashed into little bits. The fronts of all the surrounding houses were pierced with hundreds of holes, large and small. The street itself was filled with débris and was impassable:

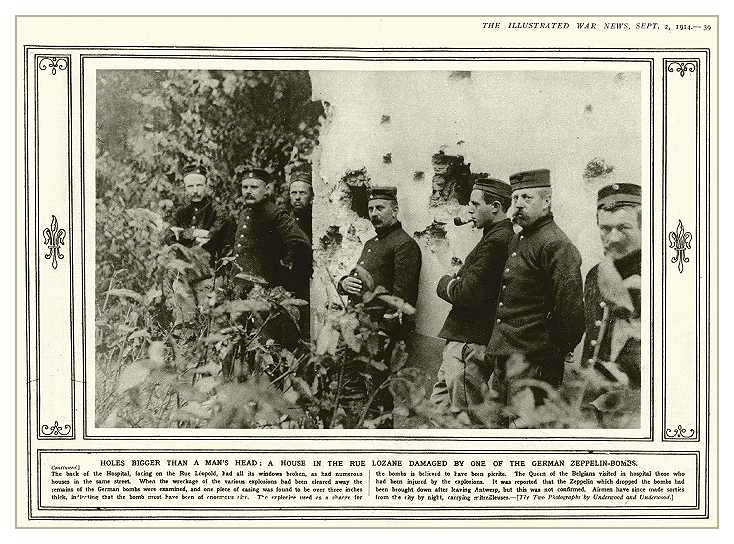

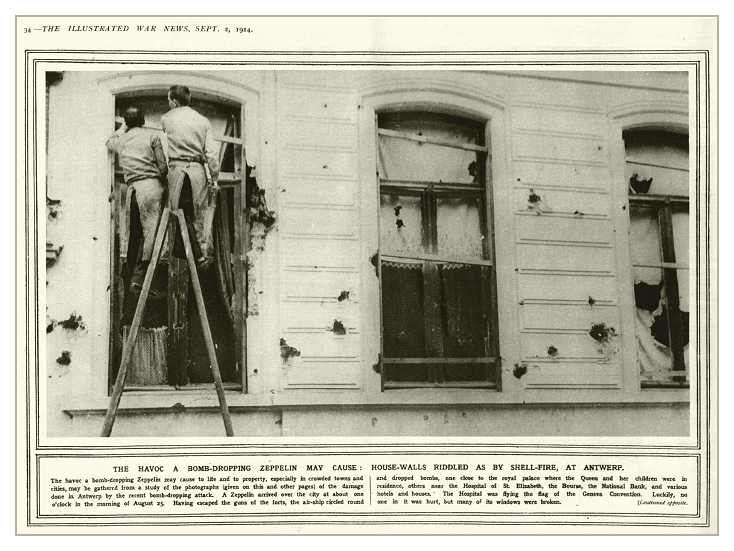

From this place we went to the other points where bombs had fallen. As we afterward learned, ten people were killed outright; a number have since died of their injuries, and a lot more are injured, and some of these may die. A number of houses were completely wrecked and a great many will have to be torn down. Army officers were amazed at the terrific force of the explosions. The last bomb dropped as the Zeppelin passed over our heads fell in the centre of a large square - La Place du Poids Publique. It tore a hole in the cobblestone pavement, some twenty feet square and four or five feet deep. Every window in the square was smashed to bits. The fronts of the houses were riddled with holes, and everybody had been obliged to move out, as many of the houses were expected to fall at any time.

The Dutch Minister's house was near one of the smaller bombs and was damaged slightly. Every window was smashed. All the crockery and china are gone; mirrors in tiny fragments; and the Minister somewhat startled. Not far away was Faura, the First Secretary of the Spanish Legation. His wife had been worried sick for fear of bombardment, and he had succeeded only the day before in prevailing upon her to go to England with their large family of children. Another bomb fell not far from the houses of the Consul-General and the Vice-Consul- General, and they were not at all pleased. The windows on one side of our hotel were also smashed.

We learned that the Zeppelin had sailed over the town not more than five hundred feet above us; the motor was stopped some little distance away and she slid along in perfect silence and with her lights out. It would be a comfort to say just what one thinks about the whole business. The purr of machine guns that we heard after the explosion of the last bomb was the starting of the motor, which earned our visitor out of range of the guns which were trundled out to attack her. Preparations were being made to receive such a visit, but they had not been completed; had she come a day or two later, she would have met a warm reception. The line of march was straight across the town, on a line from the General Staff, the Palace where the Queen was staying with the Royal children, the military hospital of Ste. Elisabeth, filled with wounded, the Bourse, and some other buildings. It looks very much as though the idea had been to drop one of the bombs on the Palace. The Palace itself was missed by a narrow margin, but large pieces of the bomb were picked up on the roof and shown me later in the day by Ingelbleek, the King's Secretary. The room at the General Staff, where I had been until half an hour before the explosion, was a pretty ruin, and it was just as well for us that we left when we did. It was a fine, big room, with a glass dome skylight over the big round table where we were sitting. This came in with a crash and was in powder all over the place. Next time I sit under a glass skylight in Antwerp I shall have a guard outside with an eye out for Zeppelins.

If the idea of this charming performance was to inspire terror, it was a complete failure. The people of the town, far from yielding to fear, are devoting all their energies to anger. They are furious at the idea of attempting to kill their King and Queen. There is no telling when the performance will be repeated, but there is a chance that next time the balloon man will get a warmer reception.

In the morning I went around and called at the Foreign Office, which is established in a handsome building that belonged to one of the municipal administrations. The Minister for Foreign Affairs took me into his office and summoned all hands to hear any news I could give them of their families and friends. I also took notes of names and addresses of people in Brussels who were to be told that their own people in Antwerp were safe and well. I had been doing that steadily from the minute we set foot in the hotel the night before, and when I got back here I had my pockets bulging with innocent messages. Now comes the merry task of getting them around.

At the hotel we were besieged with invitations to lunch and dine with all our friends. They were not only had to see somebody from the outside world, but could not get over the sporting side of our trip, and patted us on the back until they made us uncomfortable. Everybody in Antwerp looked upon the trip as a great exploit, and exuded admiration. I fully expected to get a Carnegie medal before I got away. And it sounded so funny coming from a lot of Belgian officers who had for the last few weeks been going through the most harrowing experiences, with their lives in danger every minute, and even now with a perfectly good chance of being killed before the war is over. They seem to take that as a matter of course, but look upon our performance as in some way different and superior. People are funny things.

I stopped at the Palace to sign the King's book, and ran into General Jungbluth, who was just starting off with the Queen. She came down the stairs and stopped just long enough to greet me and then went her way; she is a brave little woman and deserves a better fate than she has had. Ingelbleek, the King's Secretary, heard that I was there signing the book and came out to see me. He said that the Queen was anxious I should see what had been done by the bombs of the night before. He wanted me to go right into the houses and see the horrid details. I did not want to do this, but there was no getting out of it under the circumstances.

We drove first to the Place du Poids Publique and went into one of the houses which had been partially wrecked by one of the smaller bombs. Everything in the place had been left as it was until the police magistrate could make his examination and report. We climbed to the first floor, and I shall never forget the horrible sight that awaited us. A poor policeman and his wife had been blown to fragments, and the pieces were all over the walls and ceiling. Blood was everywhere. Other details are too terrible even to think of. I could not stand any more than this one room. There were others which Ingelbleek wanted to show me, but I could not think of it. And this was only one of a number of houses where peaceful men and women had been so brutally killed while they slept.

And where is the military advantage of this? If the bombs were dropped near the fortifications, it would be easy to understand, but in this instance it is hard to explain upon any ground, except the hope of terrifying the population to the point where they will demand that the Government surrender the town and the fortifications. Judging from the temper they were in yesterday at Antwerp, they are more likely to demand that the place be held at all costs rather than risk falling under the rule of a conqueror brutal enough to murder innocent people in their beds.

The Prime Minister told me that he had four sons in the army - all the children he has- and that he was prepared to give every one of them, and his own life and fortune, into the bargain, but that he was not prepared-and here he banged his fist down on the table and his eyes flashed - to admit for a minute the possibility of yielding to Germany. Everybody else is in the same state of mind. It is not hysterical. The war has been going on long enough, and they have had so many hard blows that the glamour and the fictitious attractiveness of the thing have gone, and they have settled down in deadly earnest to fight to the bitter end. There may not be one stone left upon another in Belgium when the Germans get through, but if these people keep up to their present level they will come through - what there is left of them - free.

Later in the afternoon I went to the Foreign Office and let them read to me the records of the Commission which is investigating the alleged German atrocities.

They are working in a calm and sane way and seem to be making the most earnest attempt to get at the true facts, no matter whether they prove or disprove the charges that have been made. It is wonderful to see the judicial way they can sit down in the midst of war and carnage and try to make a fair inquiry on a matter of this sort. If one one-thousandth part of the charges are proven to be true.

………..

To make sure of offering no unnecessary chances for Mr. Zeppelin the authorities had ordered all the lights on the streets put out at eight o’clock. It was dark at midnight and there was no use in thinking of venturing out into the town. It was the city of the dead. Guns were posted in the streets ready for instant use in case the airship should put in another appearance. As a result of this and the searchlights that played upon the sky all night, our friend the enemy did not appear. Some people know when they have had enough.

Several photos of damage done to civilian homes