The Execution of a British Nurse

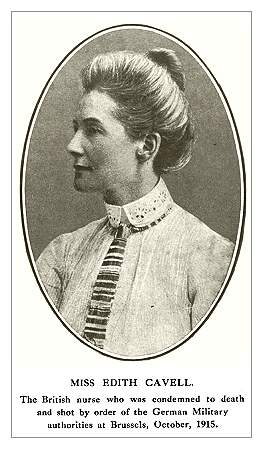

left : portrait of Miss Cavell

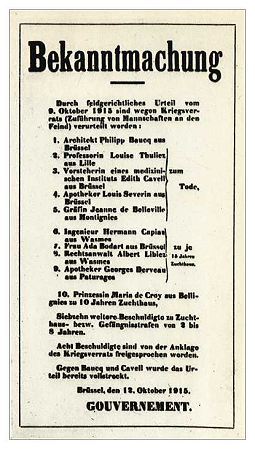

right : article from a French newspaper 'Excelsior'

I : EDITH CAVELL

Early in August Brussels had heard, and all Belgium - or at least all that part of Belgium that lived in chateaux - had heard, that the Princess Maria de Croy and the Countess Jeanne de Belleville had been arrested. The de Croys are one of the oldest families of the Belgian nobility, and the Princess Maria was a maiden lady who lived almost in seclusion in her chateau of Bellignies, near Mons. The Countess Jeanne de Belleville lived not far away, at her chateau of Montignies-sur-Roc, near Andregnies, in the province of Hainaut. These two distinguished ladies had been arrested for having aided British soldiers to pass the Belgian frontier, and were accused of "treason in time of war." At the beginning of the war the Princess de Croy had established a Red Cross hospital in her chateau, where Belgian, English, and German wounded were cared for. After the Battle of Mons a great many British soldiers, cut off in the retreat, had been left behind in Belgium, and all through the winter and spring had lived the lives of hunted animals in the woods or in the farms and fields of Hainaut and of Brabant. Near the chateau of the Princess de Croy thirteen British soldiers had hidden in a haystack on a Belgian farm, and, tracked down at last by German soldiers, they were taken and shot without mercy. This so affected the Princess that she determined to organize a method whereby British soldiers, finding themselves in a position that in all civilized countries would have entitled them at least to the consideration shown to prisoners of war, could be cared for and if possible got out of the country. And, though frail and in delicate health, she and the Countess de Belleville and Mademoiselle Thuliez and certain others organized a system to aid those British soldiers who were still in hiding and to send them to Brussels, where, as she declared in her interrogatory before the military tribunal, she thought they would be less rigorously dealt with than at Mons, which was under the military regime of the Etappengebiet. The Princess did not know what became of them after they reached Brussels ; others aided them to get across the frontier into Holland.

One day in August it was learned at the Legation that an English nurse named Edith Cavell had been arrested by the Germans. I wrote a letter to the Baron von der Lancken to ask if it was true that Miss Cavell had been arrested, and saying that if it were I should request that Maitre de Leval, the legal counsellor of the Legation, be permitted to see her and to prepare for her defence. There was no reply to this letter, and on September 10, I wrote a second letter, repeating the questions and the requests made in the first. On September 12, I had a reply from the Baron stating that Miss Cavell had been arrested on August 5, that she was confined in the prison of St.-Gilles, that she had admitted having hidden English and French soldiers in her home as well as Belgians of an age to bear aims, all anxious to get to the front; that she had admitted also having furnished these soldiers with money to get to France, and had provided guides to enable them to cross the Dutch frontier;, that the defence of Miss Cavell was in the hands of Maitre Thomas Braun, and that inasmuch as the German Government, on principle, would not permit accused persons to have any interviews whatever, he could not obtain permission for Maitre de Leval to visit Miss Cavell as long as she was in solitary confinement.

We at the Legation had not at the time seen anything more serious in the case than in the numerous other cases that were similarly brought to our notice, or of which we were constantly hearing. It was the German practice in Belgium to arrest any one "on suspicion," as we should say in America, and to investigate the facts afterward. Under the German system in vogue in Belgium, as Maitre Théodor had not feared some months before to point out to the authorities, persons who were arrested were not told of the offence with which they were charged, nor were the offences themselves clearly defined; so that Miss Cavell, like many another who has shared her fate, was arrested and held in prison while the secret police continued their investigations and made up the dossier which would reveal its secrets only before a military court, that was at once prosecutor, jury, and judge.

For one of our Anglo-Saxon race and legal traditions to understand conditions in Belgium during the German occupation it is necessary to banish resolutely from the mind every conception of right that we have inherited from our ancestors-conceptions long since crystallized into immutable principles of law and confirmed in our charters of liberty. In the German mentality these conceptions do not exist: the Germans think in other sequences, they act according to another principle, if it is a principle - the conviction that there is only one right, one privilege, and that it belongs exclusively to Germany; the right, namely, to do whatever they have the physical force to do. These so-called courts, of whose arbitrary and irresponsible and brutal nature I have tried to give some notion, were mere inquisitorial bodies, guided by no principle save that inherent in their own bloody nature; they did as they pleased, and would have scorned a Jeffrys as too lenient, a Lynch as too formal, a Spanish auto do fé as too technical, and a tribunal of the French Revolution as soft and sentimental. Before them the accused had literally no rights; he could not even, as a right, present a defence, and if he was permitted to speak in his own behalf it was only as a generous and liberal favour.

Long months before, a clergyman, an American citizen, had been arrested and held for several days at the Kommandantur without the knowledge of any one at the Legation; the fact came to our knowledge only accidentally. I was able to secure the liberation of this American, however, and then I asked the Politische Abteilung to notify me and to permit me to present a defence whenever any American citizen, or a citizen of any country whose interests were confided to my care, was arrested. The Politische Abteilung agreed to this, but we usually learned of such incidents before the Politische Abteilung could notify us, and provided a lawyer to look after the interests of the accused, so far as it was possible to do that before a German military court martial. The defence, as I have just said, was not a defence in our meaning of the word. The lawyer was not allowed to see his client until he appeared to plead the case before the court where the accused was arraigned for trial, and he was not permitted to speak to his client during the trial; often he did not know what the accusation was until the trial began, and sometimes he did not know it even then. There were no written charges and no specifications, much less an indictment or information. The secret police would bring before the bench of German officers sitting there in the Senate chamber all the evidence, as they called it, that they had been able to collect, and present it as they pleased, with no concern as to its pertinence or relevancy. The court would admit hearsay, presumptions, conclusions, inferences, and innuendoes so long as they were on behalf of the prosecution; there was no cross-examination, sometimes even no interrogatory on the part of the presiding judge. The accused was sometimes allowed to present a defence, but it was generally only such as he might contrive in sparring with the judges as they questioned him. He had no process for witnesses in his own behalf, and no right to have them heard even when they were willing to appear.

After the evidence was in, the officer, a kind of judge-advocate, who acted as prosecutor, would state the penalty that he thought applicable, and the court would vote to apply it. The lawyer for the defence, after having gone through the case without any possibility of preparation, without even having spoken to his client before or during the trial, and with no admitted principles to guide him, without the right to present testimony in rebuttal, would be allowed to make a statement or an argument. But, as though he were not already labouring under a disadvantage sufficiently heavy, he must be careful in his argument not to say anything that would reflect in the least on one of the witnesses, especially if the witness happened to be a German soldier, or even a German civilian; he must not contradict a judge-advocate or question the validity or propriety of any act of the prosecution, for this would be equivalent to contempt of court and amount to the heinous offence of failing in respect to the German army. He must show the most exquisite and exaggerated respect for the court, and as a result he could only stand there niddy-noddying, pale with fear, and say nothing. In a word, even when the judgments of those extraordinary tribunals reflected a kind of natural justice, which perhaps they did on occasion, the whole proceeding was the veryest travesty and mockery. The judges could be swayed by any passion, any prejudice, any whim, and when the accused happened to be some one who had offended the secret police or Messieurs les militaires the judgment was a foregone conclusion-unless he was a personage, especially a titled personage, and then he was apt to be shown a snobbish consideration.

It was before such a court that Edith Cavell was to be arraigned. I had asked Maitre de Leval to provide for her defence, and on his advice, inasmuch as Maitre Thomas Braun was already counsel in the case, chosen by certain friends of Miss Cavell, I invited Maitre Braun into consultation. Maitre Braun was a Belgian lawyer of standing and ability; his father was defending the most distinguished of the accused, the Princess de Croy. He was a man thoroughly equipped, who had the advantage of knowing German as well as he knew French, and had appeared constantly and not without success before the German tribunals. I asked Maitre Braun to appear, then, for Miss Cavell, representing the American Legation.

It was supposed at first that the case was no more likely to result in tragedy than the generality of cases brought before such tribunals; that is, that it was one of those numerous cases in which Belgians were being condemned to deportation to some German prison, like Madame Carton de Wiart or Maitre Théodor, to mention the most celebrated, or if one were to consider the cases of those less prominent, the many convictions and sentences to imprisonment for terms of years-two or ten or twenty. They all amounted to the same thing - those terms of imprisonment, for the victims would be freed at the conclusion of peace if they lived, and if peace were ever concluded.

It was not until weeks had passed that we heard that the charges to be brought against Miss Cavell were serious, but still we were in mystery; all we could learn was that " the instruction was proceeding," and that things were taking their course. Then we were told that the offence with which she would be charged was that of aiding young men to cross the Dutch frontier.

I think that we were somewhat relieved; such cases were common, and the sentences provided in them were not in general severe, according to the standard of those in vogue in occupied Belgium.

Edith Cavell herself did not expect such a fate. She was a frail and delicate little woman about forty years of age. She had come to Brussels some years before to exercise her calling as a trained nurse, and soon became known to the leading physicians of the capital and in the homes of the leading families. But she was ambitious and devoted to her profession, and ere long had entered a nursing-home in the Rue de la Clinique, where she organized for Dr. Depage a training school for nurses. She was a woman of refinement and education; she knew French well ; - she was deeply religious, with a conscience almost Puritan, and was very stern with herself in what she conceived to be her duty. In her training school she showed great executive ability, was firm in matters of discipline, and brought it to a high state of efficiency. And every one who knew her in Brussels spoke of her with that unvarying respect which her noble character inspired.

Some time before the trial Maitre Braun informed the Legation that the Germans had forbidden him to plead before the military court and that some one else would have to appear for Miss Cavell; he suggested Maitre Sadi Kirschen, who was engaged. I had thought of asking to have Maitre de Leval attend, but on second thought, and on the advice of Maitre Sadi Kirschen, as well as that of Maitre de Leval himself, I came to the conclusion that perhaps it would not be entirely tactful to do this, for the presence of Maitre de Leval as an observer might suggest to the hypersensitive suspicions of the Germans a lack of confidence, that could only react against Miss Cavell.

It was the morning of Thursday, October 7, that the case came on before the court martial in the Senate chamber where the military trials always took place, and Miss Cavell was arraigned with the Princess de Croy, the Countess de Belleville, and thirty-two others. The accused were seated in a circle facing the court in such a way that they could neither see nor communicate with their own counsel, who were compelled to sit behind them. Nor could they see the witnesses, who were also placed behind them.

The charge brought against the accused was that of having conspired to violate the German Military Penal Code, punishing with death those who conduct troops to the enemy. Its basis in German military law is found in paragraph 68 of the German Code, which says:

Whoever, with the intention of helping the hostile Power, or of injuring the German or allied troops, is guilty of one of the crimes of paragraph 90 of the German Penal Code, will be sentenced to death for treason.

Among the crimes mentioned in paragraph 90 is that of "conducting soldiers to the enemy" (dem Feinde Mannschaften zufuehrt).

We have no record of that trial; we do not know all that occurred there behind the closed doors of that Senate chamber, where for four-score years laws based on another and more enlightened principle of justice had been discussed and enacted. The lips of the lawyers who were there, and of the accused- those among the thirty-five who were acquitted-have not been unsealed, and will not be until the little land is released from the terror that daily enacts such scenes. Miss Cavell did not know, or knew only in the vaguest manner, the offence with which she was charged. No written statement of it had ever been delivered to her, no written statement of it had ever been given to her attorney, and it is a pathetic circumstance that it was her own honesty and frankness, her own direct English way of thinking, that convicted her. With the naiveté of the pure in heart she assumed that the Germans were charging her with the deeds that she had committed, and these she readily admitted, and even signed a paper to that effect. We know enough to be able to say that Miss Cavell did not deny having received at her hospital English soldiers, whom she nursed and to whom she gave money; she did not deny that she knew they were going to try to cross the border into Holland. She even took a patriotic pride in the fact. She was interrogated in German, a language she did not understand, but the questions and responses were translated into French. Her mind was alert, she was entirely calm and self-possessed, and frequently rectified inexact details in the statements that were put to her. When, in her interrogatory, she was asked if she had not aided English soldiers left behind after the early battles of the preceding autumn about Mons and Charleroi, she said yes; they were English and she was English, and she would help her own.

The answer seemed to impress the court. They asked her if she had not helped twenty.

"Yes," she said, "more than twenty; two hundred."

“English ?

"No, not all English; French and Belgians too."

But the French and Belgians were not of her own nationality, said the judge - and that made a serious difference. She was subjected to a nagging interrogatory. One of the judges said that she had been foolish to aid English soldiers, because the English are ungrateful.

No," replied Miss Cavell, "the English are not ungrateful."

"How do you know they are not ?" asked the inquisitor.

“Because," she answered, "some of them have written to me from England to thank me.

It was a fatal admission on the part of the tortured little woman; under the German military law her having helped soldiers to reach Holland, a neutral country, would have been a less serious offence, but to aid them to reach an enemy country, and especially England, was the last offence in the eyes of a German military court.

The trial was concluded on Friday, and on Sunday one of the nurses in Miss Cavell's school came to say that there was a rumour about town that the prosecuting officer had asked the court to pronounce a sentence of death on the Princess de Croy, the Countess de Belleville, Miss Cavell, and several others. The court had not as yet pronounced judgment, however, and there was some hope - or in the tribunals before which Maitre de Leval and I were used to practise there would have been some hope - that the court would not pronounce the judgment proposed. I remember to have said to Maitre de Leval, when he came up to my chamber to report this astounding news:

"That's only the usual exaggeration of the prosecutor; they all ask for the extreme penalty, everywhere, when they sum up their cases.”

"Yes," said Maitre de Leval, "and in German courts they always get it."

Maitre de Leval sent a note to Maitre Kirschen asking him to come on Monday at 8.30 o'clock to the Legation, or to send word regarding Miss Cavell. Maitre Kirschen did not send Maitre de Leval the word he had requested, and on that Sunday de Leval saw another lawyer who had been in the case and could tell him what had taken place at the trial. This lawyer thought that the court martial would not condemn Miss Cavell to death.

At any rate, no judgment had been pronounced and the judges themselves did not appear to be in agreement. On Monday, October II, at 8.30 in the morning, Maitre de Leval went to the Politische Abteilung in the Rue Lambermont, and found Conrad.

He spoke to him of the case of Miss Cavell and asked that, now that the trial had taken place, he and the Reverend Mr. H. Stirling T. Gahan, the British chaplain at Brussels and rector of the English church, be allowed to see Miss Cavell.

Conrad said he would make inquiries and inform de Leval by telephone, and by one of the messengers of the Legation who that morning happened to deliver some papers to the Politische Abteilung Conrad sent word that neither the Reverend Mr. Gahan nor Maitre de Leval could see Miss Cavell at that time, but that Maitre de Leval could see her as soon as the judgment had been pronounced. At 11.30 o'clock on that Monday morning Maitre de Leval himself telephoned to Conrad, who repeated this statement. The judgment had not yet been rendered, he said, and Maitre de Leval asked Conrad to inform him as soon as the judgment was pronounced, so that he might go to see Miss Cavell. Conrad promised this, but added that even then the Reverend Mr. Gahan could not see her because there were German pastors at the prison, and that if Miss Cavell needed spiritual advice or consolation she could call on them. Conrad concluded this conversation by saying; that the judgment would be rendered probably on the morrow - that is, on Tuesday-or the day after, and that even when it had been pronounced it would have to be signed by the Military Governor before it was effective and that the Legation would be kept informed.

Maitre de Leval is one of the most meticulously exact men that I ever knew. The instant he had an important conversation of any sort he used to dictate the purport of it to a stenographer, and thus he always had a record of everything-the date, the hour, precisely what was said and done. In preparing this account I have had the benefit of a glance at Maitre de Leval's own notes. Shortly after noon on that Monday, not having received any news from Maitre Kirschen, Maitre de Leval went to his house, but did not find him there and left his card. He then went to the house of the lawyer to whom reference has already been made and left word for him to call at his house. At four o'clock that afternoon the lawyer went to Maitre de Leval and said that he had gone to see the Germans at eleven o'clock, and that there he had been told that no judgment would be pronounced before the following day. On leaving the Legation to go home Maitre de Leval told all that had happened to Gibson, and asked him to telephone again to Conrad before going home himself.

Thus at intervals all day long the inquiry had been repeated, and the same response made. Monday evening, at 6.20 o'clock Belgian time, Topping, one of the clerks of the Legation, with Gibson standing by, again called Conrad on the telephone, again was told that the judgment had not been pronounced and that the Political Department would not fail to inform the Legation the moment the judgment was confirmed. And then the Chancellery was closed for the night.

II. THE NIGHT OF THE EXECUTION

At nine o'clock that Monday evening Maitre de Leval appeared suddenly at the door of my chamber; his face was deathly pallid. He said that he had just heard from the nurses who were keeping him informed, that the judgment had been confirmed and that the sentence of death had been pronounced on Miss Cavell at half-past four that afternoon, and that she was to be shot at two o'clock the next morning. It seemed impossible, especially the immediate execution of sentence; there had always been time at least to prepare and to present a plea for mercy. To condemn a woman in the evening and then to hurry her out to be shot before another dawn! Preposterous!

But no; Maitre de Leval was certain. That evening he had gone home and was writing at his table when, about eight o'clock, two nurses were introduced. One was Miss Wilkison, "petite et nerveuse, toute en larmes," the other "plus grande et plus calme." Miss Wilkison said that she had just learned that the court had condemned Miss Cavell to death, that the judgment had been read to her in the cell of the prison at four-thirty that afternoon, and that the Germans were going to shoot her that night at two o'clock. Maitre de Leval told her that it was difficult to believe such news since twice he had been told that the judgment had not been rendered and would not be rendered before the following day, but on her reiterating that she had this news from a source that was indisputable de Leval left at once with her and her friend, and tame to the Legation. And there he stood, pale and shaken. Even then I could not believe-it was too preposterous; surely a stay of execution would be granted. Already in the afternoon, in some premonition, Maitre de Leval had prepared for my signature a ‘recours en grace’ to be submitted to the Governor-General, and a letter of transmittal to present to the Baron von der Lancken. I asked Maitre de Leval to bring me these documents, and signed them.

I told Maitre de Leval to send Joseph at once to hunt up Gibson to present the plea, and if possible to find the Marquis de Villalobar and to ask him to support it with the Baron von der Lancken. Gibson was dining somewhere; we did not know where Villalobar was. The Politische Abteilung, the Ministry of Industry, where Baron von der Lancken lived, was only half a dozen blocks away. The Governor-General was in his chateau at Trois-Fontaines, ten miles away, playing bridge that evening. Maitre de Leval went. The nurses from Miss Cavell's school were waiting in a lower room. Other nurses came for news; they too had heard, but could not believe Then the Reverend Mr. Gaham pastor of the English church, came. He had had a note from some one at the St. Gilles prison - a note written in German, saying simply: "Come at once; someone is about to die."

He went away to the prison; his frail, delicate little wife remained at the Legation, and there my wife and Miss Lamer sat with those women all that long evening, trying to comfort, to reassure them. Outside a cold rain was falling. Up in my chamber I waited. . . . A stay of execution would be granted, of course ; they always were granted. There was not in our time, anywhere, a court, even a German court martial, that would condemn a woman to death at half-past four in the afternoon and hurry her out and shoot her before dawn.

Midnight came, and Gibson, with a dark face, and de Leval, paler than ever. There was nothing to be done. De Leval had gone to Gibson and together they went in search of the Marquis, whom they found at Baron Lambert's, where he had been dining; he and Baron Lambert and M. Francqui were over their coffee. The Marquis, Gibson, and de Leval went to the Rue Lambermont. The Ministry was closed and dark; no one was there. They rang, and rang again, and finally the concierge appeared-no one was there, he said. They insisted. The concierge at last found a German functionary, who came down, stood staring stupidly; every one was gone; His Excellency was at the theatre. At what theatre? He did not know. They urged him to go and find out. He disappeared inside, went up and down the stairs two or three times, finally came out and said that he was at "Le Bois Sacré." They explained that the presence of the Baron was urgent and asked the man to go for him; they turned over the motor to him and he mounted on the box beside Eugene. They reached the little variety theatre in the Rue d'Arenberg. The German functionary went in and found the Baron, who said he would come when the piece was over.

All this while Villalobar, Gibson, and de Leval were in the salon at the Ministry, the room of which I have spoken so often as the yellow salon because of the satin upholstery of its Louis XVI furniture of white lacquer-that bright, almost laughing little salon, all done in the gayest, lightest tones, where so many little dramas were played. All three of them were deeply moved and very anxious - the eternal contrast, as de Leval said, between sentiments and things. Laucken entered at last,- very much surprised to find them; he was accompanied by Count Harrach and by the young Baron von Falkenhausen.

"What is it gentlemen ? " he said. "Has something serious happened?"

They told him why they were there, and Lancken, raising his hands, said': Impossible!

He had vaguely heard that afternoon of a condemnation for "spying" (sic), but he did not know that it had anything to do with the case of Miss Cavell, and in any event it was impossible that they would put a woman to death that night.

"Who has given you this information? For, really, to 'come and disturb me at such an hour you must have information from serious' and trustworthy sources.

De Leval replied: "Without doubt, I consider my information trustworthy, but I must refuse to tell you from whom I received it. Besides, what difference does it make ? If the information is true our presence at this hour is justified; if it is not true I am ready to take the consequences of my mistake."

The Baron showed irritation.

"What! " he said, "it is because they say that you come and disturb me at such an hour,. me and these gentlemen? No, no, gentlemen, this news cannot be true; orders are never executed with such precipitation, especially when a woman is concerned. Come to see me to-morrow."

He paused, and then added: "Besides, how do you think that at this hour I can obtain any information. The Governor-General must certainly be sleeping."

Gibson, or one of them, suggested to him that a very simple way of finding out would be to telephone to the prison.

"Quite right," he said; "I had not thought of that."

He went out, was gone a few minutes, and came back embarrassed, so they said, even a little bit ashamed, for he said “You are right, gentlemen; I have learned by telephone that Miss Cavell has been condemned, and that she will be shot to-night."

Then de Leval drew out the letter that I had written to the Baron and gave it to him, and he read it in an undertone-with a little sarcastic smile, so de Leval said-and when he had finished he handed it back to de Leval and said: “But it is necessary to have a plea for mercy at the same time.”

Here it is," said de Leval, and he gave him the document. Then they all sat down.

I could see the scene-as it was described to me by Villalobar, by Gibson, by de Leval, in that pretty little salon Louis seize that I knew so well - Lancken giving way to an outburst of feeling against "that spy," as he called Miss Cavell, and Gibson and de Leval by turns pleading with him, the Marquis sitting by. It was not a question of spying, as they pointed out; it was a question of the life of a woman-a life that had been devoted to charity, to the service of others. She had nursed wounded soldiers, she had even nursed German wounded at the beginning of the war, and now she was accused of but one thing: of having helped British soldiers make their way toward Holland. She may have been imprudent, she may have acted against the laws of the occupying Power, but she was not a spy, she was not even accused of being a spy, she had not been convicted of spying, and she did not merit the death of a spy. They sat there pleading, Gibson and de Leval, bringing forth all the arguments that would occur to men of sense and sensibility. Gibson called Lancken's attention to their failure to inform the Legation of the sentence, of their failure to keep the word that Conrad had given. He argued that the offence charged against Miss Cavell had long since been accomplished, that as she had been for some weeks in prison a slight delay in carryipg out the sentence could not endanger the German cause; he even pointed out the effect such a deed as the summary execution of the death sentence against a woman would have 6n public opinion, not only in Belgium but in America and elsewhere; he even spoke of the possibility of reprisals.

But it was all in vain. Baron von der Lancken explained to them that the Military Governor-that is, General von Sauberzweig-was the supreme authority (Gerichtsherr) in matters of this sort, that the Governor-General himself had no authority to intervene in such cases, and that under the provisions of German martial law it lay within the discretion of the Military Governor to accept or refuse an appeal for clemency. And then Villalobar suddenly cried out: "Oh, come now! It's a woman; you can't shoot a woman like that!"

The Baron paused, was evidently moved. “Gentlemen, it is past eleven o'clock; what can be done?”

It was only Von Sauberzweig who could act, he said, and they urged the Baron to go to see Von Sauberzweig. Finally he consented. While he was gone, Villalobar, Gibson, and de Leval repeated to Harrach and Von Falkenhausen all the arguments that might move them. Von Falkenhausen was young, he had been to Cambridge in England, and he was touched, though of course he was powerless. And de Leval says that when he gave signs of showing pity Harrach cast a glance at him, so that he said nothing more, and that then Harrach said: "The life of one German soldier seems to us much more important than those of all these old English nurses. .

At last Lancken returned and, standing there, announced: “I am exceedingly sorry, but the Governor tells me that it is after due reflection that the execution was decided upon, and that he will not change his decision. . . . Making use of his prerogative, he even refuses to receive the plea for mercy. . . Therefore, no one, not even the Emperor, can do anything for you."

With this he handed my letter and the ‘requete en grace’ to Gibson. There was a moment of silence in the yellow salon. Then Villalobar sprang up, and seizing Lancken by the shoulder said to him in an energetic tone: “Baron, I insist on speaking to you!”

“C'est inutile . . ." began Laucken

"Je veux vous parler!" the Marquis replied, giving categorical emphasis to the harsh imperative.

The old Spanish pride had been mounting in the Marquis, and he literally dragged the tall Von der Lancken into a little room near by; then voices were heard in sharp discussion, and even through the partition the voice of Villalobar:

"It is idiotic, this thing you are going to do; you will have another Louvain!"

A few moments later they came back - Villalobar in silent rage, Lancken very red. And, as de Leval said, without another word, dumb, in consternation, filled with an immense despair, they came away.

I heard the report, and they withdrew. A little while and I heard the street door open. The women who had waited all that night went out into the rain.

III. AN EX-POST FACTO EDICT

The rain had ceased and the air was soft and warm the next morning; the sunlight shone through an autumn haze. But over the city the horror of the dreadful deed hung like a pall. Affiches were early posted and crowds huddled about them in a kind of stupefaction, reading the long and tragic list down to the line that closed with a piece of gratuitous brutality:

Of the twenty-six others condemned with Miss Cavell, four - Philippe Baucq, an architect of Brussels, Louise Thuliez; a school-teacher at Lille, Louis Severin, a pharmacist of Brilssels; and the Countess Jeanne de Belleville, of Montignies-sur-Roc - were sentenced to death. Herman Capiau, a civil engineer of Wasmes, Madame Ada Bodart, of Brussels, Albert Libiez, a lawyer of Wasmes, and Georges Derveau, a pharmacist of Paturages, were sentenced each to fifteen years penal servitude at hard labour. The Princess Maria de Croy was sentenced to ten years penal servitude at hard labour. Seventeen others were sentenced to hard labour or to terms of imprisonment of from two to eight years. The eight remaining were acquitted.

All day long sad and solemn groups stood under the trees in the boulevards amid the falling leaves gazing at the grim affiche. In one of the throngs a dignified old judge said: "Ce n'etait pas l'exécution d'un jugement; c'etait un assassinat !”

The horror of it pervaded the house. I found my wife weeping at evening; no need to ask what was the matter. The wife of the chaplain had been there, with some detail of Miss Cavell's last hours - how she had risen wearily from her cot at the coming of the clergyman, drawn her dressing-gown about her thin throat.

I sent a note to the Baron von der Lancken asking that the Governor-General permit the body of Miss Cavell to be buried by the American Legation and the friends of the dead girl. t In reply the Baron himself came to see me in the afternoon. He was solemn and said that he wished to express his regret in the circumstances, but that he had done all that he could. The body, he said, had already been interred, with respect and with religious rites, in a quiet place, and under the law it could not be exhumed without an order from the Imperial Government. The Governor-General himself had gone to Berlin.

And then came Villalobar ; I thanked him for what he had done. He told me much, and described the scene the night before in that ante-room with Lancken. The Marquis was much concerned about the Countess Jeanne de Belleville and Mademoiselle Thuliez, both French, and hence protogées of his, condemned to die within eight days, but I told him not to be concerned; that the effect of Miss Cavell's martyrdom did not end with her death - it would procure other liberations, these among them. The thirst for blood had been slaked and there would be no more executions in that group; it was the way of the law of blood vengeance. We talked a long time about the tragedy, and about all the tragedies that went to make up the larger tragedy of the war.

"We are getting old," he said. "Life is going, and after the war, if we live in that new world, we shall be of the old - the new generation will push us aside."

Gibson and de Leval prepared reports of the whole matter and I sent them by the next courier to our Embassy at London.

But somehow that very day the news got out into Holland and shocked the world. Richards, of the C R B., just back from The Hague, said that they had already heard of it there and were filled with horror. And even the Germans, who seemed always to do a deed and to consider its effect afterwards, knew that they had another Louvain, another Lusitania, for which to answer before the bar of civilization. The lives of the three who remained of the five who had been condemned to death were

ultimately spared, as I had told Villalobar they would be. The President of the United States and the King of Spain made representations at Berlin on behalf of the Countess de Belleville and Mademoiselle Thuliez, and their sentences were commuted to imprisonment, as was that of Louis Severin, the Brussels druggist. The storm of universal loathing and reprobation for the deed was too much even for the Germans.

The affiche announcing the execution of the sentence Against Miss Cavell was not the only one on the walls of Brussels that morning. There were others, among them one that announced that a Belgian soldier-Pierre Joseph Claes, of Schaerbeek, a suburb of Brussels-had been condemned at Limbourg and shot as a spy,*

IV. MISS CAVELL'S LAST NIGHT

Our rector, Mr. Gahan, whose services and sacrifices during all those sad and brutal times were c9nsoling to so many, was the last representative of her own people to see Miss Cavell. He had gone from the Legation to the prison of St.-Gilles, and his wife was among the women waiting on that night at the Legation. Mr. Gahan was with Miss Cavell all that evening, and though they would not let him be with her at the very last, it is the one ameliorating circumstance of the tragedy that the German chaplain was kind.

When Mr. Gahan arrived at the prison that night Miss Cavell was lying on the narrow cot in her cell; she rose, drew on a dressing-gown, folded it about her thin form, and received him calmly. She had never expected such an end to the trial, but she was brave and was not afraid to die. The judgment had been read to her that afternoon there in her cell. She had written letters to her mother in England and to certain of her friends, and entrusted them to the German authorities.

She did not complain of her trial; she had avowed all, she said-and it is one of the saddest, bitterest ironies of the whole tragedy that she seems not to have known that all she had avowed was not sufficient, even under German law, to justify the judgment passed upon her. The German chaplain had been kind and she was willing for him to be with her at the last, if Mr. Gahan could not be. Life had not been all happy for her, she said, and she was glad to die for her country. Life bad been hurried, and she was grateful for those weeks of rest in prison.

She had no hatred for any one, and she had no regrets; she received the sacrament.

"Patriotism is not enough," she said. "I must have no hatred and no bitterness toward any one.

Those, so far as we know, were her last words. She had been told that she would b& called at five o'clock. . . . At six they came, and the black van conveyed her and the architect Baucq to the Tir National - where they were shot. Miss Cavell was brave and calm at the last, and she died facing the firing-squad - another martyr in the old cause of human liberty.

In the touching report that Mr. Gahan made there is a statement - one of the last that Edith Cavell ever made - which in its exquisite pathos illuminates the whole of that life of stern duty, of human service and martyrdom. She said that she was grateful for the ten weeks of rest she had just before the end. During those weeks she had read and reflected; her companions and her solace were her Bible, her Prayer Book, and "The Imitation of Christ." The notes she made in these books reveal her thoughts at that time and will touch the uttermost depths of any nature nourished in that beautiful faith which is at once so tender and so austere. The Prayer Book, with those laconic entries on its flyleaf in which she set down the sad and eloquent chronology of her fate, the copy of the "Imitation" which she had read and marked during those weeks in prison-weeks which, as she so pathetically said, had given her rest and quiet and time to think in a life that ha4 been "so hurried "-and the passages noted in her firm hand, all have a deep and appealing pathos.

Just before the end she wrote a number of letters; she forgot no one. Among the letters that she left was one addressed to the nurses of her school, and there was a message for a girl who was trying to break herself of the morphine habit. Miss Cavell had been trying to help her, and she sent word telling her to be brave, and that if God would permit she would continue to try to help her.

It was on October 10, 1915, already doomed to death, that Miss Cavell wrote the letter to her nurses. The letter was in French, for all the nurses were Belgian girls, and in it, after expressing the sorrow she felt in bidding adieu to her pupils, she wrote of the joy she had had in being called on September '7, 1907, to organize at Brussels the first school of graduate nurses in Belgium. At that time nursing had not been made a science in Belgium as it had been in England and in America; the graduate nurse was unknown. Dr. Depage, one of the leading physicians in Belgium - one of the leading physicians, indeed, in the world-had been anxious that such a school be founded, and it was through his inspiration and that of his wife that the school was made possible. They succeeded in interesting in the project a number of influential men and women in Brussels, Antwerp, Bruges, Liege, and Mons; a society was formed, and Madame Ernest Solvey gave to the school the sum of 500,000 francs, with which was built the model hospital and training school for nurses that stands now in the Rue de Bruxelles in Uccle. The building had fifty rooms for nurses and thirty rooms for patients, study halls, theatres for operations, and represented the ideas of Dr. Depage, of Madame Depage, and of Miss Cavell. The building was completed in the month of May 1915 - the very month that Madame Depage went down on the Lusitania, and five months before Miss Cavell was killed-and, by the operation of the old ironic smile of life, neither of the two women most concerned ever saw established in it the school they had founded. Miss Cavell, in organizing and establishing this school, encountered very real difficulties in those first years, for, as she says in her letter, " tout était nouveau dans la profession pour la Belgique." She was evidently a woman of great force of will and of nervous energy; she had a high intelligence and a profound character, and she succeeded. She established the school, she established nursing in Belgium, and her name and that of Madame Depage, both victims of German frightfulness,, will ever be associated with the institution at Brussels.

The letter, with its stern command of emotion and feeling, though all the while deep down there is an affection that somehow fears to express itself, so finds the profound depths of the Anglo-Saxon nature, and it somehow sums up the character that made a noble and devoted life. When one thinks that there in her cell behind the grim walls of the prison of St.-Gilles this frail woman sat down and in a firm hand, and in a foreign language, almost without a fault, wrote such. a letter as this, one understands something of her nature. She gives a glimpse of the difficulties she had to overcome in order to found her school in a peculiarly conservative milieu where all was new and strange. She remembers Some of the obscure but tragic conflicts that were going on in the souls of those whom she; was directing. She had been. a strong disciplinarian, a self-contained nature, which she had completely mastered, sternest always with herself; and in asking those girls, who may not always have understood her, O forgive what they may have considered her severity, she was with the touching confession that she loved them more than they knew.

She left several other letters, one for her mother in England, that were turned over to the German authorities to be delivered, but they were never delivered. Again and again I asked for them, begging to be allowed to send them to England to comfort the aged and sorrowing mother, but they refused to give them over. They said that if I were to send them to England they would be published abroad and another sensation created that would react against the German cause. I was able later to give them my word that they would not be published, that they would remain the sacred secret of the mother for whom they were intended; but no, they would not give them up - the military would not consent. But the officer in whose keeping they were did have the grace to say to me finally:

"I wish I might give them to you; they are a very sad and uncomfortable charge for me to keep."

V. THE REACTION

Why was Miss Cavell singled out among the others as the one to be shot at dawn on the morning after condemnation? Why, if justice, even rude military justice, were being done, were not all shot who had been condemned to death? Why this signal distinction, this marked and tragic discrimination? Because Edith Cavell was English; that was her offence. And so they slew her, those generals with stars on their breasts and iron crosses, bestowed for bravery and gallantry-slew the nurse who had cared for their own wounded soldiers. They could not even await the unfolding of their own legal processes; they could not wait even the few days they had allotted to the Countess de Belleville, to Mademoiselle Thuliez, or to Severin the Belgian, although the Countess and Mademoiselle Thuliez, if all that is now known of the complot and the trial is true, were as deeply involved as Miss Cavell. They had been associated in a conspiracy, if the word may be employed, to aid British soldiers to escape; the only fact that saved the Princess de Croy was her declaration that after the men reached Brussels she did not know what became of them. But Messieurs les militaires must hide their intentions, perhaps even from their own colleagues in the Government of Occupation, and shuffle their frail victim out by stealth in the night, like midnight garrotters and gunmen, because she was English. The armies of Great Britain were just then making an offensive, and it was partly in petty spite for this, partly an expression of the violent hatred the Germans bore everything English, the savage feeling that had been fostered and kept alive and fanned into a furious flame by historians and Herr Professors and Herr Doktors and Herr Pastors, and editors with their editorials and harangues and hymns of hate, that they did what they did. It was in that spirit that they pronounced their judgment secretly in her prison cell and hurried her out and slew her before dawn should come and another day in which the voice of pity and of humanity could get itself heard. They could not wait for that, and they would not disturb Von Bissing there at his game of bridge in the chateau at Trois-Fontaines.

We were told that according to the German law, whatever that may mean, it was only the Military Governor in the jurisdiction in which the so-called crime had been committed who had the power to receive or to grant a plea for mercy. I do not know as to that; German military law seems to be whatever Messieurs les mititaires are moved at the moment to call it. Von Sauberzweig said that he alone had the power to receive our plea for mercy, or even to grant a few hours' delay; be accepted the responsibility.

Baucq, the Brussels architect, was shot that morning because it would have been too bald, too patent, even from the Prussian viewpoint, to hurry out a woman all alone and kill her. And so it was Baucq's sinister luck to be chosen for a fate that might have been no worse than that of Severin, or the others whose lives were saved. Poor Baucq has not often been mentioned in connexion with this tragedy. He was no less illegally condemned, no less foully done to death, but his fate was swallowed up in the greater horror of the assassination of his companion of that tragic dawn at Etterbeek. He left a wife and two children. One of them was a little girl of twelve, who, several days after, went to a neighbour's and asked if she might come in and be alone for a while.

I wish to weep for my father," she said, " but I do not like to do it before mamma; I must be brave for her."

There were heroisms even among the Belgian children.

Miss Cavell, as I have said, did not deny having aided British soldiers and Belgian lads by giving them food and clothing and lodging and money. The thirty-five who were tried were said to be concerned in a combination of wide extent-more than seventy persons were said to be included in it-to help men over the frontier into Holland. More than seven thousand young men, it was said, had gone out during the months of June, July, and August.

Miss Cavell was ideally situated to aid such patriotic work. Her nursing home offered an exceptional pied-a-terre. The Germans had apparently convinced themselves, at least, that among the seventy whom they had arrested they had the ringleaders of a formidable organization and that they had undone the knot of the conspiracy that had been carrying on so extensively the work of recruiting for the Allied armies. They determined to break it up, and they employed their favourite weapon- Fuerchterlichkeit. What would make a deeper impression on the mind, or instill greater fear in the hearts of the people, than to take a woman out and shoot her-this calm, courageous little woman with the stern lips and the keen grey eyes that were not afraid? And then she was English-the unpardonable offence.

It is possible that the men at the Politische Abteilung did not know, that Monday afternoon, that the judgment had been pronounced. Messieurs les militaires had an affair in hand, and they had set their hearts on carrying it out; and they may not have told them at the Politische Abteilung, may have kept the truth from their colleagues, or, with that contempt they always had for the civil department of government, may have warned them to keep their hands off. It may be that the Political Department did not care, or did not dare, to interfere. If the military party had deceived or ignored them, they, of course, in the solidarity and discipline that binds all Germans, would not have given that fact as an excuse. The excuse they did give was that Maitre de Leval had led the American Legation into error, and that, anyway, even if Conrad had told Maitre de Leval what he did tell him, neither Conrad nor Maitre de Leval had any diplomatic quality, and that therefore the German authorities had not deceived the American Legation. The first excuse is not founded on fact, the second rests upon a distinction too trivial to give it any moral or legal value. Maitre de Leval did not lead us into error; Conrad did tell him and did tell Toppjng, either honestly believing what he said or having been instructed to say-it must be one or the other or both-that no judgment had been rendered, when, as a matter of fact, that judgment had been rendered hours before.

There is a curious variance between tht statements of the Germans that I have never been able to explain. The affiche of the German Government which announced the death of Miss Cavell begins: ' Par jugement du 9 octobre" ("By judgment of the 9th October"). This statement as to the time of the rendition of the judgment is opposed to all the declarations made by the Germans to representatives of the Legation. Miss Cavell's trial took place on October 7 and 8, and on the 11th de Leval, Gibson, and Topping, who made inquiries, were informed that the judgment had not yet been pronounced and would not be pronounced for several days. The judgment, or the final and formal judgment, Was not pronounced until the 11 h, at 4.30 in the afternoon in the prison of St.-Gilles, and hours afterward Conrad again said that it had not been pronounced and would not be pronounced for a day or two. Either the affiche is mistaken or the officials at the Politische Abteilung were mistaken, or the phrase "Par jugement du 9 octobre" means something else in the German mind than it does in our minds. If the judgment was rendered on October 9 then the action of the Germans is even more odious than ever3 and could be explained on no hypothesis consistent with lionourable conduct, for if the judgment were rendered on October 9, as the official announcement of the German Government states, then their verbal communications to the Legation of the 11th were unspeakable in their cynical disregard of facts. I am of the opinion that the judgment was rendered on October II and that the statement in the affiche is inexact, or else the action of the 9th was in the nature of a verdict and that of the 11th in the nature of a death sentence.

There were many stories of how the Princess and the Countess and Miss Cavell and the others were betrayed: there was the tale of the post card sent to Miss Cavell by the boy whose indiscreet gratitude betrayed his benefactor; there was another that would have it that there was a lad, a messenger somewhere down in the Borinage, who, angry because his pay was not at once forthcoming, betrayed his employers. And only lately I heard a fantastic tale to the effect that one of the accused was a somnambulist who talked in his sleep, and that the Germans, as always, strong on science and modern methods, hypnotized him and so obtained the facts. The story is hardly sufficient for our Anglo-Saxon notions of evidence, and others claimed that the explanation was somewhere to be found in another dark tragedy which some months later shocked that Brussels so accustomed to tragedy.

In the letter that Miss Cavell wrote to her nurses there is a reference to the evil of gossip which is of immense significance not only were happiness and reputations destroyed by idleness, she says, but life itself sacrificed. It is not for me; or any one, to penetrate the sacred precincts of the brave soul of Edith Cavell in that solemn hour, but the references may have been, in part at least, due to the fact that she found herself condemned to death because of some unrestrained and indiscreet tongues that had betrayed her.

It is no small prudence to keep silence in an evil - she wrote in her copy of the "Imitation "- the most pathetic, perhaps, of all the lines she wrote, and the nearest expression of anything like reproach that she ever made.

I shall refer to that other tragedy in its place, but for us at the American Legation there was a sequel a week later. I had had Gibson's and de Leval's reports sent over to the American Embassy at London, and there they were turned over by our Ambassador to the Foreign Office and given out to the Press for publication. They were published far and wide-and in consequence the Rotterdamsche Courant and the other Dutch newspapers were not allowed on sale in Brussels that next day. The closing of the frontier to newspapers was an invariable sign, well known in Brussels, that the Germans were not satisfied with the state of things, and we soon heard that the authorities, were very angry and had even intimated that the Governor-General might have to send all the diplomats away in consequence." It was, of course, the policy of terrorization transferred to the diplomatic field, but it was a menace that held few terrors for us. Our situation was not enviable.

The Germans had a copy of the London Times over at the Politische Abteilung, with our reports spread out in full through all its broad columns, and were greatly agitated. Even little Conrad, much moved, had exclaimed to Villalobar:

"Tres bien," said the Marquis, "vous etes devenu fameux, un des gros bonnets de l'Europe."

Then we heard that the German rage was especially directed against de Leval for having made a report at all, and that they threatened to send him to a concentration camp in Germany. That was on Saturday, the 23rd. I was convalescing; my physician had told me that I might go to work again, and I had made an appointment to see the Baron von der Lancken on the following Monday to discuss a reprise du travail - an appointment that had been postponed several times already by my illness. It was raining heavily when Monday came, and Dr. Derscheid came to give me a piqure and to tell me not to go out; but I went.

The Baron von der Lancken, just from his morning ride, booted, with his Iron Cross and other ribbons, the white cross of St. John on his side, and a large dossier under his arm, received me with a dark, glowering face, asked me upstairs to his little workroom where a fire was burning, and when seated he began solemnly.

And then he went on to say that the diplomats had remained in Brussels by courtesy of the Germans, that the publication of my report in the Cavell case was a great injustice to Germany and a breach of diplomatic etiquette, that our Legation was furnishing an arm to England, Germany's enemy, that it was an unneutral act, etc. All these. observations and others like them were conveyed in phrases that were diplomatically correct, but in the manner of conveying them there was an evident feeling and I know not what of irritation and resentment that revealed or reflected the temper of Messieurs les militaires, smarting, no doubt, under the sting of that universal opprobrium which had surprised them with its lash, and of course trying in their rage to shift the blame for a deed the consequences of which they had apparently been unable to foresee. It was. as I have already reported, a habit, I might almost say a policy of theirs, to open discussions that involved their manners and morals in a way that was intended to put their opponents or their interlocutors at once in the wrong, and I interrupted the Baron then, and he adopted a less emphatic tone.

"Let us talk the matter over unofficially and in a friendly way, and try to reach some conclusion," he said.

This was better, and we discussed the case in all its bearings. He had copies of the Times and of the Morning Post before him, marked with red and blue pencils. His objections, it soon developed, were not to the report so much as to the fact that the report had been published, though by reason of what he alleged as misstatements in de Leval's report he kmself had been accused of having broken his promise; He said that I, officially, as American Minister, had not made frequent inquiries, that it was de Leval who had spoken to Conrad, and that neither de Leval nor Conrad had any diplomatic quality. What he wished then, at the end, was that r express regret at the publication and that de Leval instantly be dismissed from the Legation; otherwise he could not be responsible for what would happen to him. Already the military had threatened to arrest and deport him.

To this I replied that I was responsible for de Leval and for his actions, that I would not dismiss him, and that my Legation would be his asylum if any effort were made to molest him.

"You don't think me capable of throwing him to the wolves and letting this Sauberzweig eat him alive!" I exclaimed.

And as for regrets, I said that I would not express any, nor make any statement unless instructed by my Government so to do.

We talked calmly and frankly perhaps as never before, both recognizing in our conversation the fact that the relations between our Governments were still strained over the Lusitania case. We spoke of the ravitaillement, and the danger involved to it in any disagreement; but even so, I said, rather than seem to shirk any responsibility or to abandon de Leval, I should prefer to withdraw from Belgium. At this he protested, begged me not to mention such a thing, suggested that Villalobar join the discussion- to which I consented, of course, with pleasure - and we parted, to meet again that afternoon. And in the end he shook hands twice and inquired solicitously about my health.

At three o'clock that afternoon, in the yellow salon downstairs, the Baron and the Marquis and I met, and Baron you der Lancken outlined the whole subject again; on the table before him were copies 'of the London newspapers, with the Graphic, or some illustrated journal, containing my portrait and one of Villalobar - the Marquis in a yachting-cap, at Cowes - thirty years before, he said with a sigh.

Baron von der Lancken was especially bitter against de Leval. He said that de Leval was persona non grata, and that his presence compromised our neutrality. I told him that of course if de Leval was persona non grata he could be eliminated, though not as a punishment, and only after communication with Washington.

We talked all afternoon-a terrible afternoon. I was weary and depressed-weary of the long strain, weary of negotiations in French of all accents, and I was still seedy and under the horror of that awful night. The cold rain was falling in the Park. . . The Baron was anxious and even insistent that I make a statement, in writing, that would absolve the German authorities by admitting inaccuracies in the report made by de Leval and express regret at its publication; he had a sheet of paper and a pencil ready to write it all down. But I declined to make such a statement or any statement or to authorize any expression in the nature of an excuse, a disavowal, or a regret.

So it was left. Van Vollenhoven was waiting to join us in the discussion of the reprise du travail. He came in and I hurried the business through; every one, indeed, was tired except Van Vollenhoven, and possibly Villalobar, who seemed never to get tired.

The next day Baron von der Laucken went to Munich. The Governor-General had gone to Berlin. The President and the King of Spain had made appeals to the Government at Berlin on behalf of the Countess de Belleville and Mademoiselle Thuliez, and Villalobar and I felt that their lives were saved, at any rate. And Severin, who was a Freemason, had friends who were working, in his behalf. Some one brought to the Legation and committed to my care Miss Cavell's Prayer Book, with its touching entries, written in her own hand, firmly, that last night, with the verses of Scripture that had given her comfort, and then, last entry of all - written while she was yet alive and life still pulsing within her, when, in a world otherwise ordered, long years of devoted service might have been hers-the legend, the epitaph that need not yet have been: "Died at 7 a.m. on Oct. 12th, 1915."

There were a few francs and a few precious trinkets, all her poor little belongings. And yet-how vast, how noble, how rich an estate

The modest English nurse whose strange fate it was to be so suddenly summoned from the dim wards of sickness and of pain to a place among the world's heroes and martyrs will have, in happier, freer times, her monument in Brussels ; some street or public place will bear her name, the school she founded will be called after her and continue her mission of healing in the earth. And when the horror of her cruel and unjust fate shall have faded somewhat in the light of its emergent sacrifice, the few lines she wrote and the simple words she spoke as she was about to die will remain to reveal the heights that human nature may attain, and to sanctify a memory that will be revered as long as faith and honour are known to men.