- 'the Last Hours of Edith Cavell

- on the Night of Her Execution'

- Experience of American Diplomat in Effort to Save Life of English Nurse

- Told by Hugh Gibson, Secretary of American Legation at Brussels

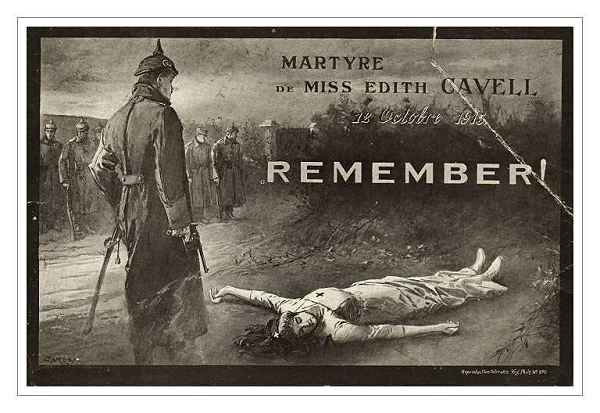

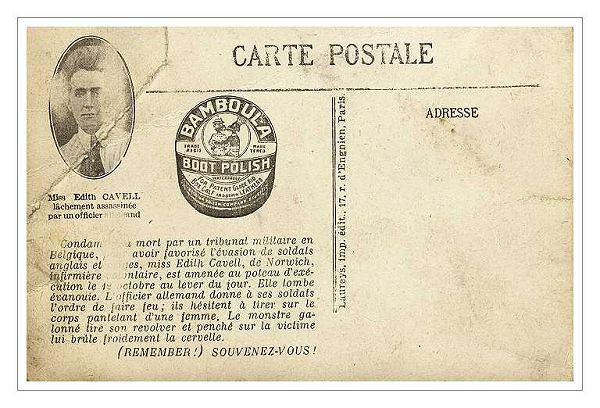

The Execution of a British Nurse

front and back of a French postcard

This is the official story of the events on the midnight just before the execution of Edith Cavell, the English nurse, who became the first woman martyr of the Great War. Hugh Gibson here relates how, with the Spanish Minister and a Belgian counsellor, he went to the house of the German Governor at Brussels late at night and pleaded with Baron von der Lancken and the German officers for a stay of execution. The American Minister, Brand Whitlock, too ill to make the journey himself, waited at the American Embassy for the results of the mission. The story is told in the official report to Minister Whitlock, which was forwarded to the British Government. The narrative given herewith is from Mr. Gibson's statement in the World's Work, with introductory reports from other sources.

1 — Story of the Execution of Edith Cavell

Edith Cavell was an English nurse, daughter of the late Rev. Frederick Cavell, former Vicar of Swardeston, Norfolk. The charge against her was aiding Belgians to escape to England. It is stated she hid them in her house and provided them with money and addresses in England and helped to smuggle them across the frontier.

Miss Cavell was confined in prison ten weeks. Her trial before the military court of Brussels lasted two days. M. De Leval, Belgian Counsellor for the American Legation, tells this story:

"Herr Kirscher assured me repeatedly that the Military Court always was perfectly fair and that he would keep me informed of all developments in the case, but he failed to give me any information and after the trial I learned from other sources the following:

"Miss Cavell was prosecuted for having helped English and French soldiers, as well as Belgian young men, to cross the frontier and go to England. She admitted by signing a statement before the day of the trial and by public acknowledgment in court that she was guilty of the charges, not only that she had helped these soldiers to cross the frontier, but also that some of them had thanked her in writing when arriving in England.

"This last admission made her case more serious, because if it had only been proved she had helped soldiers to traverse the Dutch frontier and no proof was produced that those soldiers had reached a country at war with Germany, she could have only been sentenced for an attempt to commit the crime, and not for the crime being duly accomplished.

"Miss Cavell, in her oral statement before the court, disclosed almost all the facts of the prosecution. She spoke without trembling and showed a clear mind, and often added some greater precision to her previous depositions.

"When she was asked why she helped these soldiers to go to England she replied that she thought if she had not done so they would have been shot by the Germans. Therefore she thought she only did her duty to her country in saving their lives.

"The military prosecutor said the argument might be good for English soldiers, but that it did not apply to Belgian young men, who would have been perfectly free to remain in the country without danger to their lives. The German military court found her guilty and sentenced her to death by shooting."

The execution took place at 2 o'clock in the morning (October 12, 1915) immediately after the American and Spanish diplomats left the house of the German Governor, who refused their appeals.

The execution ground was a garden or yard in Brussels surrounded by a wall. A German firing party of six men and an officer was drawn up in the garden and awaited its victim. She was led in by soldiers from a house nearby, blindfolded with a black scarf. Up to this minute the woman, though deadly white, had stepped out bravely to meet her fate, but before the rifle party her strength at last gave out and she tottered and fell to the ground thirty yards or more from the spot where she was to have been shot.

The officer in charge of the execution walked to her. She lay prone on the ground, motionless. The officer then drew a large service revolver from his belt, took steady aim from his knee and shot the woman through the head as she lay on the floor (this version is denied by the German authorities). The firing party looked on. The officer quietly returned his revolver to its case and ordered the soldiers to carry the body to the house, where charge was taken of it by a Belgian woman, acting under the instructions of the Spanish Minister, who had undertaken the responsibility for the body pending arrangements for the burial.

M. De Leval, a Belgian counsellor, makes this statement of Edith Cavell's last message:

"This morning Mr. Gahan, an English clergyman, told me that he had seen Miss Cavell in her cell yesterday night at 10 o'clock and that he had given her the Holy Communion and had found her admirably strong and calm. I asked Mr. Gahan whether she had made any remarks about anything concerning the legal side of her case, and whether the confession she made before trial and in court was in his opinion perfectly free and sincere. Mr. Gahan said she told him she was perfectly well and knew what she had done; that, according to the law, of course she was guilty, and admitted her guilt, but that she was happy to die for her country." *

II — Story of Hugh Gibson, American Diplomat

When we got to the Political Department we found that Baron von der Lancken and all the members of his staff had gone out to spend the evening at one of the disreputable little theatres that have sprung up here for the entertainment of the Germans. At first we were unable to find where he had gone, as the orderly on duty evidently had orders not to tell, but by dint of some blustering and impressing on him the fact that Lancken would have cause to regret not having seen us, he agreed to have him notified. We put the orderly into the motor and sent him off. The Marquis de Villalobar De Leval and I settled down to wait, and we waited long, for Lancken, evidently knowing the purpose of our visit, declined to budge until the end of an act that seemed to appeal to him.

He came in about 10:30, followed shortly by Count Harrach and Baron von Falkenhausen, members of his staff. I briefly explained to him the situation as we understood it, and presented the note from the minister transmitting the appeal for clemency. Lancken read the note aloud in our presence, showing no feeling aside from cynical annoyance at something — probably our having discovered the intentions of the German authorities.

When he had finished reading the note Lancken said that he knew nothing of the case, but was sure in any event that no sentence would be executed so soon as we had said. He manifested some surprise, not to say annoyance, that we should give credence to any report in regard to the case which did not come from his department, that being the only official channel. Leval and I insisted, however, that we had reason to believe our reports were correct and urged him to make inquiries. He then tried to find out the exact source of our information, and became insistent. I did not propose, however, to enlighten him on this point, and said that I did not feel at liberty to divulge our source of information.

Lancken then became persuasive — said that it was most improbable that any sentence had been pronounced; that even if it had, it could not be put into effect within so short a time, and that in any event all government offices were closed and that it was impossible for him to take any action before morning. He suggested that we all go home "reasonably," sleep quietly, and come back in the morning to talk about the case. It was very clear that if the facts were as we believed them to be the next morning would be too late, and we pressed for immediate inquiry. I had to be rather insistent on this point, and De Leval, in his anxiety, became so emphatic that I feared he might bring down the wrath of the Germans on his own head, and tried to quiet him. There was something splendid about the way De Leval, a Belgian, with nothing to gain and everything to lose, stood up for what he believed to be right and chivalrous, regardless of consequences to himself.

Finally, Lancken agreed to inquire as to the facts, telephoned from his office to the presiding judge of the court-martial, and returned in a short time to say that sentence had indeed been passed and that Miss Cavell was to be shot during the night.

We then presented with all the earnestness at our command the plea for clemency. We pointed out to Lancken that Miss Cavell's offences were a matter of the past; that she had been in prison for some weeks, thus effectually ending her power for harm; that there was nothing to be gained by shooting her, and, on the contrary, this would do Germany much more harm than good and England much more good than harm. We pointed out to him that the whole case was a very bad one from Germany's point of view; that the sentence of death had heretofore been imposed only for cases of espionage, and that Miss Cavell was not even accused by the German authorities of anything so serious. At the time there was no intimation that Miss Cavell was guilty of espionage. It was only when public, opinion had been aroused by her execution that the German government began to refer to her as "the spy Cavell." According to the German statement of the case, there is no possible ground for calling her a spy. We reminded him that Miss Cavell, as directress of a large nursing home, had, since the beginning of the war, cared for large numbers of German soldiers in a way that should make her life sacred to them. I further called his attention to the manifest failure of the Political Department to comply with its repeated promises to keep us informed as to the progress of the trial and the passing of the sentence. The deliberate policy of subterfuge and prevarication by which they had sought to deceive us as to the progress of the case was so raw as to require little comment. We all pointed out to Lancken the horror of shooting a woman, no matter what her offence, and endeavored to impress upon him the frightful effect that such an execution would have throughout the civilized world. With a sneer he replied that, on the contrary, he was confident that the effect would be excellent.

When everything else had failed we asked Lancken to look at the case from the point of view solely of German interests, assuring him that the execution of Miss Cavell would do Germany infinite harm. We reminded him of the burning of Louvain and the sinking of the Lusitania, and told him that this murder would rank with those two affairs and would stir all civilized countries with horror and disgust. Count Harrach broke in at this with the rather irrelevant remark that he would rather see Miss Cavell shot than have harm come to the humblest German soldier, and his only regret was that they had not "three or four old English women to shoot."

The Spanish Minister and I tried to prevail upon Lancken to call Great Headquarters, at Charleville, on the telephone and have the case laid before the Emperor for his decision. Lancken stiffened perceptibly at this suggestion and refused, frankly — saying that he could not do anything of the sort. Turning to Villalobar, he said, "I can't do that sort of thing. I am not a friend of my sovereign as you are of yours," to which a rejoinder was made that in order to be a good friend one must be loyal and ready to incur displeasure in case of need. However, our arguments along this line came to the point of saying that the military governor of Brussels was the supreme authority (Gerichtsherr) in matters of this sort, and that even the Governor General had no power to intervene. After further argument he agreed to get General von Sauberschweig, the military governor, out of bed to learn whether he had already ratified the sentence and whether there was any chance for clemency.

Lancken was gone about half an hour, during which time the three of us labored with Harrach and Falkenhausen, without, I am sorry to say, the slightest success. When Lancken returned he reported that the military governor had acted in this case only after mature deliberation ; that the circumstances of Miss Cavell's offence were of such a character that he considered infliction of the death penalty imperative. Lancken further explained that under the provisions of German military law the Gerichtsherr had discretionary power to accept or to refuse to accept an appeal for clemency; that in this case the Governor regretted that he must decline to accept the appeal for clemency or any representations in regard to the matter.

We then brought up again the question of having the Emperor called on the telephone, but Lancken replied very definitely that the matter had gone too far; that the sentence had been ratified by the military governor, and that when matters had gone that far "even the Emperor himself could not intervene." (Although accepted at the time as true, this statement was later found to be entirely false and is understood to have displeased the Emperor. The Emperor could have stopped the execution at any moment.)

Despite Lancken's very positive statements as to the futility of our errand, we continued to appeal to every sentiment to secure delay and time for reconsideration of the case. The Spanish Minister led Lancken aside and said some things to him that he would have hesitated to say in the presence of Harrach, Falkenhausen and De Leval, a Belgian subject. Lancken squirmed and blustered by turns, but stuck to his refusal. In the meantime, I went after Harrach and Falkenhausen again. This time, throwing modesty to the winds, I reminded them of some of the things we had done for German interests at the outbreak of the war; how we had repatriated thousands of German subjects and cared for their interests; how during the siege of Antwerp I had repeatedly crossed the lines during actual fighting at the request of Field Marshal von der Goltz to look after German interests; how all this service had been rendered gladly and without thought of reward; that since the beginning of the war we had never asked a favor of the German authorities, and it seemed incredible that they should now decline to grant us even a day's delay to discuss the case of a poor woman who was, by her imprisonment, prevented from doing further harm, and whose execution in the middle of the night at the conclusion of a course of trickery and deception was nothing short of an affront to civilization. Even when I was ready to abandon all hope, De Leval was unable to believe that the German authorities would persist in their decision, and appealed most touchingly and feelingly to the sense of pity for which we looked in vain.

Our efforts were perfectly useless, however, as the three men with whom we had to deal were so completely callous and indifferent that they were in no way moved by anything that we could say.

We did not stop until after midnight, when it was only too clear that there was no hope.

It was a bitter business leaving the place feeling that we had failed and that the little woman was to be led out before a firing squad within a few hours. But it was worse to go back to the legation to the little group of English women who were waiting in my office to learn the result of our visit. They had been there for nearly four hours while Mrs. Whitlock and Miss Larner sat with them and tried to sustain them through the hours of waiting. There were Mrs. Gahan, wife of the English chaplain; Miss B. and several nurses from Miss Cavell s school. One was a little wisp of a thing who had been mothered by Miss Cavell, and was nearly beside herself with grief. There was no way of breaking the news to them gently, for they could read the answer in our faces when we came in. All we could do was to give them each a stiff drink of sherry and send them home. De Leval was white as death, and I took him back to his house. I had a splitting headache myself and could not face the idea of going to bed. I went home and read for awhile, but that was no good, so I went out and walked the streets, much to the annoyance of German patrols. I rang the bells of several houses in a desperate desire to talk to somebody, but could not find a soul — only sleepy and disgruntled servants. It was a night I should not like to go through again, but it wore through somehow, and I braced up with a cold bath and went to the legation for the day's work.

The day brought forth another loathsome fact in connection with the case. It seems the sentence on Miss Cavell was not pronounced in open court. Her executioners, apparently in the hope of concealing their intentions from us, went into her cell, and there, behind locked door, pronounced sentence upon her. It's all of a piece with the other things they have done.

On October 11 Mr. Gahan got a pass and was admitted to see Miss Cavell shortly before she was taken out and shot. He said she was calm and prepared, and faced the ordeal without a tremor. She was a tiny thing that looked as though she could be blown away with a breath, but she had a great spirit. She told Mr. Gahan that soldiers had come to her and asked her to be helped to the frontier; that, knowing the risks they ran and the risks she took, she had helped them. She said she had nothing to regret, no complaint to make, and that if she had it all to do over again she would change nothing.

They partook together of the Holy Communion, and she who had so little need of preparation was prepared for death. She was free from resentment and said: "I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness toward any one."

She was taken out and shot before daybreak.

She was denied the support of her own clergyman at the end, but a German military chaplain stayed with her and gave her burial within the precincts of the prison. He did not conceal his admiration, and said: "She was courageous to the end. She professed her Christian faith and said that she was glad to die for her country. She died like a heroine."

- left - a canticle composed in Miss Cavell's honor

- right - a commemoration parade in war-time London