- 'A British Reporter Visits Vermelles'

- by Philip Gibbs

- from his book 'Now It can Be Told'

Visiting the Ruins of a French Village

- from a french magazine 'Le Pays de France' : the ruins of Vermelles village in 1915

- see also a French language text : La Prise de Vermelles

Just at first--though not for long--there was a touch of hostility against us among divisional and brigade staffs, of the Regulars, but not of the New Army. They, too, suspected our motive in going to their quarters, wondered why we should come "spying around," trying to "see things." I was faintly conscious of this one day in those very early times, when with the officer who had been a ruler in India I went to a brigade headquarters of the 1st Division near Vermelles. It was not easy nor pleasant to get there, though it was a summer day with fleecy clouds in a blue sky. There was a long straight road leading to the village of Vermelles, with a crisscross of communication trenches on one side, and, on the other, fields where corn and grass grew rankly in abandoned fields. Some lean sheep were browsing there as though this were Arcady in days of peace. It was not. The red ruins of Vermelles, a mile or so away, were sharply defined, as through stereoscopic lenses, in the quiver of sunlight, and had the sinister look of a death-haunted place. It was where the French had fought their way through gardens, walls, and houses in murderous battle, before leaving it for British troops to hold. Across it now came the whine of shells, and I saw that shrapnel bullets were kicking up the dust of a thousand yards down the straight road, following a small body of brown men whose tramp of feet raised another cloud of dust, like smoke. They were the only representatives of human life--besides ourselves--in this loneliness, though many men must have been in hiding somewhere. Then heavy "crumps" burst in the fields where the sheep were browsing, across the way we had to go to the brigade headquarters.

"How about it?" asked the captain with me. "I don't like crossing that field, in spite of the buttercups and daisies and the little frisky lambs."

"I hate the idea of it," I said.

Then we looked down the road at the little body of brown men. They were nearer now, and I could see the face of the officer leading them--a boy subaltern, rather pale though the sun was hot. He halted and saluted my companion.

"The enemy seems to have sighted our dust, sir. His shrapnel is following up pretty closely. Would you advise me to put my men under cover, or carry on?"

The captain hesitated. This was rather outside his sphere of influence. But the boyishness of the other officer asked for help.

"My advice is to put your men into that ditch and keep them there until the strafe is over." Some shrapnel bullets whipped the sun-baked road as he spoke.

"Very good, sir."

The men sat in the ditch, with their packs against the bank, and wiped the sweat off their faces. They looked tired and dispirited, but not alarmed.

In the fields behind them--our way--the 4.2's (four--point-twos) were busy plugging holes in the grass and flowers, rather deep holes, from which white smoke-clouds rose after explosive noises.

"With a little careful strategy we might get through," said the captain. "There's a general waiting for us, and I have noticed that generals are impatient fellows. Let's try our luck."

photograph of the chateau of Vermelles in 1915

We walked across the wild flowers, past the sheep, who only raised their heads in meek surprise when shells came with a shrill, intensifying snarl and burrowed up the earth about them. I noticed how loudly and sweetly the larks were singing up in the blue. Several horses lay dead, newly killed, with blood oozing about them, and their entrails smoking. We made a half-loop around them and then struck straight for the chateau which was the brigade headquarters. Neither of us spoke now. We were thoughtful, calculating the chance of getting to that red-brick house between the shells. It was just dependent on the coincidence of time and place.

Three men jumped up from a ditch below a brown wall round the chateau garden and ran hard for the gateway. A shell had pitched quite close to them. One man laughed as though at a grotesque joke, and fell as he reached the courtyard. Smoke was rising from the outhouses, and there was a clatter of tiles and timbers, after an explosive crash.

"It rather looks," said my companion, "as though the Germans knew there is a party on in that charming house."

It was as good to go on as to go back, and it was never good to go back before reaching one's objective. That was bad for the discipline of the courage that is just beyond fear.

a view of the chateau after the fighting

Two gunners were killed in the back yard of the chateau, and as we went in through the gateway a sergeant made a quick jump for a barn as a shell burst somewhere close. As visitors we hesitated between two ways into the chateau, and chose the easier; and it was then that I became dimly aware of hostility against me on the part of a number of officers in the front hall. The brigade staff was there, grouped under the banisters. I wondered why, and guessed (rightly, as I found) that the center of the house might have a better chance of escape than the rooms on either side, in case of direct hits from those things falling outside.

It was the brigade major who asked our business. He was a tall, handsome young man of something over thirty, with the arrogance of a Christ Church blood.

"Oh, he has come out to see something in Vermelles? A pleasant place for sightseeing! Meanwhile the Hun is ranging on this house, so he may see more than he wants."

a view of the chateau after the fighting

He turned on his heel and rejoined his group. They all stared in my direction as though at a curious animal. A very young gentleman--the general's A. D. C.--made a funny remark at my expense and the others laughed. Then they ignored me, and I was glad, and made a little study in the psychology of men awaiting a close call of death. I was perfectly conscious myself that in a moment or two some of us, perhaps all of us, might be in a pulp of mangled flesh beneath the ruins of a red-brick villa--the shells were crashing among the outhouses and in the courtyard, and the enemy was making good shooting--and the idea did not please me at all. At the back of my brain was Fear, and there was a cold sweat in the palms of my hands; but I was master of myself, and I remember having a sense of satisfaction because I had answered the brigade major in a level voice, with a touch of his own arrogance. I saw that these officers were afraid; that they, too, had Fear at the back of the brain, and that their conversation and laughter were the camouflage of the soul. The face of the young A. D. C. was flushed and he laughed too much at his own jokes, and his laughter was just a tone too shrill. An officer came into the hall, carrying two Mills bombs-- new toys in those days--and the others fell back from him, and one said:

"For Christ's sake don't bring them here--in the middle of a bombardment!"

"Where's the general?" asked the newcomer.

"Down in the cellar with the other brigadier. They don't ask us down to tea, I notice."

Those last words caused all the officers to laugh--almost excessively. But their laughter ended sharply, and they listened intently as there was a heavy crash outside.

Another officer came up the steps and made a rapid entry into the hall.

"I understand there is to be a conference of battalion commanders," he said, with a queer catch in his breath. "In view of this--er-- bombardment, I had better come in later, perhaps?"

"You had better wait," said the brigade major, rather grimly.

"Oh, certainly."

A sergeant-major was pacing up and down the passage by the back door. He was calm and stolid. I liked the look of him and found something comforting in his presence, so that I went to have a few words with him.

"How long is this likely to last, Sergeant-major"

"There's no saying, sir. They may be searching for the chateau to pass the time, so to speak, or they may go on till they get it. I'm sorry they caught those gunners. Nice lads, both of them."

He did not seem to be worrying about his own chance.

Then suddenly there was silence. The German guns had switched off. I heard the larks singing through the open doorway, and all the little sounds of a summer day. The group of officers in the hall started chatting more quietly. There was no more need of finding jokes and laughter. They had been reprieved, and could be serious.

"We'd better get forward to Vermelles," said my companion.

As we walked away from the chateau, the brigade major passed us on his horse. He leaned over his saddle toward me and said, "Good day to you, and I hope you'll like Vermelles."

The words were civil, but there was an underlying meaning in them.

"I hope to do so, sir."

We walked down the long straight road toward the ruins of Vermelles with a young soldier-guide who on the outskirts of the village remarked in a casual way:

"No one is allowed along this road in daylight, as a rule. It's under hobservation of the henemy."

"Then why the devil did you come this way?" asked my companion.

"I thought you might prefer the short cut, sir."

We explored the ruins of Vermelles, where many young Frenchmen had fallen in fighting through the walls and gardens. One could see the track of their strife, in trampled bushes and broken walls. Bits of red rag--the red pantaloons of the first French soldiers--were still fastened to brambles and barbed wire. Broken rifles, cartouches, water-bottles, torn letters, twisted bayonets, and German stick-bombs littered the ditches which had been dug as trenches across streets of burned-out houses.

A young gunner officer whom we met was very civil, and stopped in front of the chateau of Vermelles, a big red villa with the outer walls still standing, and told us the story of its capture.

a painting by French artist Galien LaLoue of the fighting at Vermelles

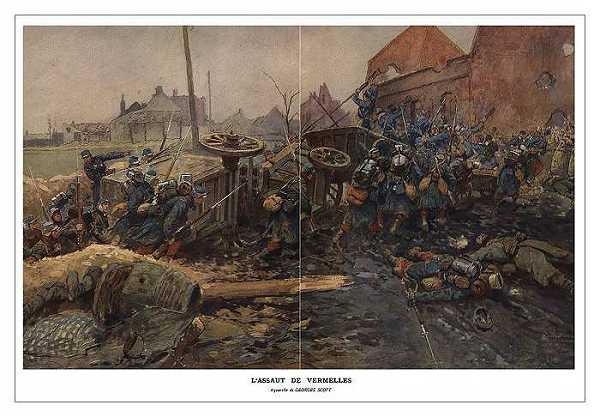

a painting by French artist Georges Scott of the fighting at Vermelles

"It was a wild scrap. I was told all about it by a French sergeant who was in it. They were under the cover of that wall over there, about a hundred yards away, and fixing up a charge of high explosives to knock a breach in the wall. The chateau was a machine-gun fortress, with the Germans on the top floor, the ground floor, and in the basement, protected by sand-bags, through which they fired. A German officer made a bad mistake. He opened the front door and came out with some of his machine-gunners from the ground floor to hold a trench across the square in front of the house. Instantly a French lieutenant called to his men. They climbed over the wall and made a dash for the chateau, bayoneting the Germans who tried to stop them. Then they swarmed into the chateau--a platoon of them with the lieutenant. They were in the drawing-room, quite an elegant place, you know, with the usual gilt furniture and long mirrors. In one corner was a pedestal, with a statue of Venus standing on it. Rather charming, I expect. A few Germans were killed in the room, easily. But upstairs there was a mob who fired down through the ceiling when they found what had happened. The French soldiers prodded the ceiling with their bayonets, and all the plaster broke, falling on them. A German, fat and heavy, fell half-way through the rafters, and a bayonet was poked into him as he stuck there. The whole ceiling gave way, and the Germans upstairs came downstairs, in a heap. They fought like wolves--wild beasts--with fear and rage. French and Germans clawed at one another's throats, grabbed hold of noses, rolled over each other. The French sergeant told me he had his teeth into a German's neck. The man was all over him, pinning his arms, trying to choke him. It was the French lieutenant who did most damage. He fired his last shot and smashed a German's face with his empty revolver. Then he caught hold of the marble Venus by the legs and swung it above his head, in the old Berserker style, and laid out Germans like ninepins. . . The fellows in the basement surrendered".

from a french magazine 'Le Pays de France' : the church at Vermelles

VI

The chateau of Vermelles, where that had happened, was an empty ruin, and there was no sign of the gilt furniture, or the long mirrors, or the marble Venus when I looked through the charred window-frames upon piles of bricks and timber churned up by shell-fire. The gunner officer took us to the cemetery, to meet some friends of his who had their battery nearby. We stumbled over broken walls and pushed through undergrowth to get to the graveyard, where some broken crosses and wire frames with immortelles remained as relics of that garden where the people of Vermelles had laid their dead to rest. New dead had followed old dead. I stumbled over something soft, like a ball of clay, and saw that it was the head of a faceless man, in a battered kepi. From a ditch close by came a sickly stench of half-buried flesh.

"The whole place is a pest-house," said the gunner.

Another voice spoke from some hiding-place.

"Salvo!"

The earth shook and there was a flash of red flame, and a shock of noise which hurt one's ear-drums.

"That's my battery," said the gunner officer. "It's the very devil when one doesn't expect it."

I was introduced to the gentleman who had said "Salvo!" He was the gunner-major, and a charming fellow, recently from civil life. All the battery was made up of New Army men learning their job, and learning it very well, I should say. There was no arrogance about them.

an artillery observation-sketch of the chateau of Vermelles in 1914

"It's sporting of you to come along to a spot like this," said one of them. "I wouldn't unless I had to. Of course you'll take tea in our mess?"

I was glad to take tea--in a little house at the end of the ruined high-street of Vermelles which had by some miracle escaped destruction, though a shell had pierced through the brick wall of the parlor and had failed to burst. It was there still, firmly wedged, like a huge nail. The tea was good, in tin mugs. Better still was the company of the gunner officers. They told me how often they were "scared stiff." They had been very frightened an hour before I came, when the German gunners had ranged up and down the street, smashing up ruined houses into greater ruin.

"They're so methodical!" said one of the officers.

"Wonderful shooting!" said another.

"I will say they're topping gunners," said the major. "But we're learning; my men are very keen. Put in a good word for the new artillery. It would buck them up no end."

We went back before sunset, down the long straight road, and past the chateau which we had visited in the afternoon. It looked very peaceful there among the trees.

It is curious that I remember the details of that day so vividly, as though they happened yesterday. On hundreds of other days I had adventures like that, which I remember more dimly.

"That brigade major was a trifle haughty, don't you think?" said my companion. "And the others didn't seem very friendly. Not like those gunner boys."

"We called at an awkward time. They were rather fussed."

"One expects good manners. Especially from Regulars who pride themselves on being different in that way from the New Army."

"It's the difference between the professional and the amateur soldier. The Regular crowd think the war belongs to them. . . But I liked their pluck. They're arrogant to Death himself when he comes knocking at the door."

from a french magazine 'Le Pays de France' : the station at Vermelles