|

|

|

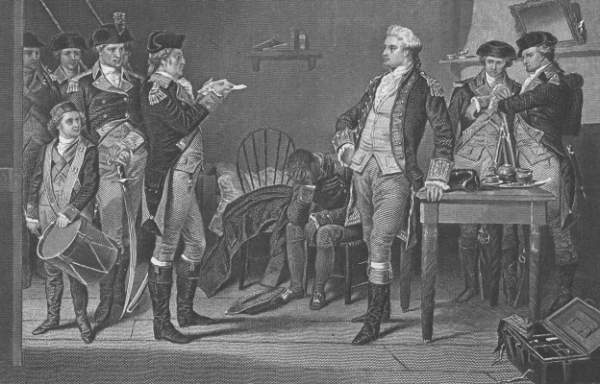

The circumstances of John André's capture, trial and execution held all the elements of a fictional tragedy, and provided fodder for dozens of prints and engravings, from 1782 to as recently as the 1980s. (The illustration above, showing André receiving his sentence, is a 19th century engraving based on a painting by Alonso Chappel.)

Washington remained intractable in the face of attempts to negotiate for the young Englishman's life, but those of his junior officers who got to know their prisoner during his captivity were not so unmoved. "From the few days of intimate intercourse I had with him," wrote Benjamin Tallmadge, (André's opposite number in the Continental Army with respect to intelligence gathering), "I became so deeply attached to Major André that I could remember no instance when my affections were so fully absorbed by any man."1

In a letter written to his fianceé on the day of André's execution, Alexander Hamilton, a member of Washington's staff, wrote angrily:

"Poor André suffers to-day. Everything that is amiable in virtue, in fortitude, in delicate sentiment and accomplished manners, pleads for him, but hard-hearted policy calls for a sacrifice. He Must die. I send you my account of Arnold's affair: and to justify myself to your sentiments, I must inform you that I urged compliance with André's request to be shot; and I do not think it would have had an ill-effect, but some people are only sensible to motives of policy and sometimes, from a narrow disposition, mistake it.

"When André's tale comes to be told, and present resentment is over, the refusing him the privilege of choosing the manner of his death will be branded with too much obstinacy.

"It was proposed to me to suggest to him the idea of an exchange for Arnold, but I knew I would have forfeited his esteem by doing it, and therefore declined it. As a man of honor, he could not but reject it, and I would not for the world have proposed to him a thing which must have placed me in the unamiable light of supposing him capable of meanness, or of feeling myself the impropriety of the measure. I confess to you, I had the weakness to value the esteem of a dying man, because I reverenced his merit."

André's trial and execution took place in the village of Tappan (or "Tappaan" as it was then spelled), New York. Located only about twelve miles from New York City, Tappan has long since been absorbed into that city's metropolitan sprawl, but a brief visit in June 2003 showed that the village still retains a surprising number of Georgian buildings, a great deal of charm -- and a plethora of historical markers relating to the case.

|

|

| While he was being tried and awaiting execution, André was held prisoner in the Mabie House, built around 1750. In 1800, it became a tavern for the second time -- having been turned to other purposes in previous years -- and has remained a public house ever since, making it one of the oldest in America. Nowadays it's a restaurant/bar called the 76 House. (It's a nice place for lunch, if you're in the neighborhood, both in terms of atmosphere and good food.) |

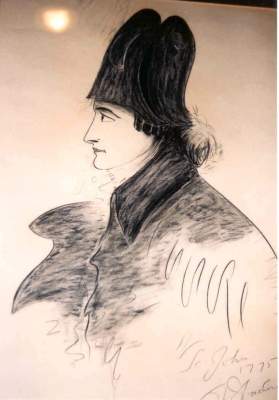

| The interior is dark and heavily timbered, with a decided André theme. Copies of contemporary and Victorian engravings of his capture and execution line the walls. This pencil self-portrait, drawn as a gift for John Cope while André was a prisoner of war in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1775, fills another corner.2 |

|

| Above the fireplace are matched images of André and Benedict Arnold, given a droll touch by the fact that Arnold's hangs upside-down. |

| And the room where André was held prisoner is now a banquet room. |

|

|

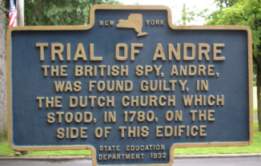

André's trial took place in the Reformed Dutch Church of Tappan. Although the site is

marked, the church itself does not survive, having been replaced by this one in 1835. According

to a plaque mounted on the building, the church was used as a hospital and prison, as well as a

courthouse, during the Revolution.

André's trial took place in the Reformed Dutch Church of Tappan. Although the site is

marked, the church itself does not survive, having been replaced by this one in 1835. According

to a plaque mounted on the building, the church was used as a hospital and prison, as well as a

courthouse, during the Revolution.

|

| A short walk up the street brings one to André Hill, the site of John's execution. Unlike the previous two sites, this one isn't well marked in the local Historical Society pamphlet, and we had a little trouble finding it. (We would have had even more if a helpful local hadn't popped his head out of a barber shop at the sight of three obviously confused people staring at a pamphlet, asked if we were looking for "The André site," and pointed us in the right direction.) |

|

André lay buried on the spot where he was hanged until his remains were returned to England, for burial in Westminster Abbey. The site was originally left unmarked, but since his disinterment, it has gone through a series of events that make an interesting saga. In The Two Spies, Nathan Hale and John André, Benson Lossing says that:

|

Two monuments have been erected at different times on the spot where André was executed. [...] One of these monuments was set up by James Lee, a public-spirited New York merchant, nearly forty years ago. It consisted of a small bowlder, upon the upper surface of which were cut the words, "ANDRÉ WAS EXECUTED OCTOBER 2, 1780." It was on the right side of a lane which ran from the highway from Tappaan village to old Tappaan, on the westerly side of a large peach-orchard, and about a mile from Washington's headquarters. I visited the spot in 1849, and made a drawing of this simple memorial-stone[.] |

A "more elegant and durable" [memorial was] placed on the same spot a few years ago by another public-spirited New York merchant, Mr. Cyrus W. Field, and bears an inscription written by the late Rev. Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, the Dean of Westminster. [...] While Dean Stanley was visiting Mr. Field [in 1878] at his country residence on the eastern bank of the Hudson, nearly opposite Tappaan, he with his two traveling companions and their host crossed the river, and, with one or two citizens of Tappaan, visited places of historic interest in the vicinity. They found that nothing marked the place of André's execution, and that it had even been a subject of controversy. The bowlder-monument had been removed several years before. The dean expressed his surprise and regret that no object indicated the locality of such an important historical event [...]3

Field said that if Dean Stanley would write the inscription he (Field) would purchase the plot of ground and build a monument to André's memory. Unfortunately, when it was announced in the paper, the offer generated a flurry of protest:

So soon as it became known that Mr. Field proposed to erect a memorial-stone at Tappaan, a correspondent of a New York morning journal denounced the intention [...] A storm of apparently indignant protests, or worse, ensued; and one writer, lacking courage to give his name, made a threat that, if Mr. Field should set up a memorial-stone upon the place where André was executed, "ten thousand men" were ready to pull it down and cast it into the river!4

Despite the threat, Field carried on with the project:

Before the visit of Mr. Field and the dean, Mr. Henry Whittemore, a public-spirited citizen of Tappan, and Secretary of the Rockland County Historical Society, had found four living men who were present at the disinterment of André's remains in 1821. With these men he went to "André Hill," where they identified the place of the spy's grave. The requisite plot of ground was secured by Mr. Field [...and o]n the 2d of October, 1879, the ninety-ninth anniversary of the execution of André, the monument prepared by Mr. Field's order, and placed over the spot where the spy was buried, was uncovered in the presence of representatives of the Historical Societies of New York, and Rockland County, of officers of the army of the United States, of the newspaper press and other gentlemen, and a few ladies. At noon, the hour of the day when André was executed, Mr. Field directed the workmen to uncover the memorial. There was no pomp or ceremony on the occasion.5

The sheer pettiness of the newspaper protests is mindboggling, considering that a century had passed since André's execution, but once Field had turned his plans into reality, worse was to come. In the years following the monument's unveiling, radicals made several attempts to destroy or deface it. (It still shows the scars). On November 3, 1885, someone tried to blow it up with dynamite, but succeeded only in shattering the pedestal. A later attempt, perhaps by the same criminal, resulted in an explosion "heard for miles around" but again failed to shatter the shaft of the monument. In between the two, someone partly defaced the inscription. Field had the memorial repaired, and turned the surrounding area into a park.6

The violence and the newspaper's accusation prompted a far more gracious response from local citizens:

Two days after that outrage, a New York morning journal of large circulation and wide influence declared that "the malignity with which the people about Tappaan regard Mr. Field's monument to André appears to be settled and permanent." To this grave indictment of the inhabitants of a portion of Rockland County as participants in the crime, people responded by resolutions unanimously adopted at an indignation meeting held at the Reformed Church at Tappaan on the evening of the 9th. They denounced the charge as utterly untrue, expressed their belief that no person in the vicinity had "the remotest connection" with the crime; that it was desirable to have the place of André's execution indicated by a memorial-stone with a suitable inscription, and commended Mr. Field for his zeal in perpetuating events of the Revolution in such a manner.7

|

Lossing provides a sketch and a description of the monument, as it was in his time:

The memorial-stone erected at Tappaan is composed of a shaft of Quincy gray granite, standing upon a pedestal of the same material. The whole structure is about nine feet in height from the ground to the apex. It is perfectly chaste in design. There is no ornamentation. The granite is highly polished. It stands upon an elevation, about two miles from the Hudson River, and thirty yards from the boundary-line between New York and New Jersey, and overlooks a beautiful country.8 |

|

| Nowadays, its situation is considerably different. Its height is more like six feet than nine, due to the final loss of the much-abused pedestal, and it stands at the center of a small roundabout in a suburban neighborhood, surrounded on one side by what looks like a parkette (we didn't have time to explore it), and on the others by modern homes. |

On its west face, it bears the following inscription, written by Dean Stanley:

|

"HERE DIED, OCTOBER 2, 1780, MAJOR JOHN ANDRÉ, OF THE BRITISH ARMY, WHO, ENTERING THE AMERICAN LINES ON A SECRET MISSION TO BENEDICT ARNOLD, FOR THE SURRENDER OF WEST POINT, WAS TAKEN PRISONER, TRIED AND CONDEMNED AS A SPY. HIS DEATH, THOUGH ACCORDING TO THE STERN RULE OF WAR, MOVED EVEN HIS ENEMIES TO PITY; AND BOTH ARMIES MOURNED THE FATE OF ONE SO YOUNG AND SO BRAVE. IN 1821 HIS REMAINS WERE REMOVED TO WESTMINSTER ABBEY. A HUNDRED YEARS AFTER THE EXECUTION THIS STONE WAS PLACED ABOVE THE SPOT WHERE HE LAY, BY A CITIZEN OF THE UNITED STATES, AGAINST WHICH HE FOUGHT, NOT TO PERPETUATE THE RECORD OF STRIFE, BUT IN TOKEN OF THOSE BETTER FEELINGS WHICH HAVE SINCE UNITED TWO NATIONS, ONE IN RACE, IN LANGUAGE, AND IN RELIGION, WITH THE HOPE THAT THIS FRIENDLY UNION WILL NEVER BE BROKEN." "ARTHUR PENRHYN STANLEY, Dean of Westminster." |

|

On the north face is a brief inscription:

"HE WAS MORE UNFORTUNATE THAN CRIMINAL."

"AN ACCOMPLISHED MAN AND GALLANT OFFICER."

GEORGE WASHINGTON.

Lossing identifies the first quote as taken from a letter of Washington to Count de Rochambeau, October 10, 1780 and the second as Washington to Colonel John Laurens on the 13th of October.

The south face has another brief inscription. The east face was originally left blank but unfortunately it is now marred by an offensive little plaque placed by the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society in 1905. It's unfortunate that they didn't handle the situation with as much grace as Dean Stanley.

Their purchase of the monument was driven by the final, though fortunately less violent, disaster which overtook it. It was described in a local paper report from the time:

THE ANDRÉ MONUMENT SOLD

Family That Owned It Failed to Pay the Taxes.

New York City, N.Y., Nov. 7 -- The monument erected by the late Cyrus W. Field, of this city, at Tappan to the memory of Major André has been sold for the non-payment of taxes. The monument stands upon André Hill, just over the spot where the British officer was buried after his death by hanging. Since the death of Mr. Field his family has neglected to pay taxes on the plot of ground, 100 feet square, within which the memorial shaft stands.

This property was one of several pieces sold recently by the county treasurer of Rockland, and when it was put up for sale there were no bidders. The amount of taxes due was $6.38, and for this sum the ground and monument were bought in by the treasurer for the county. If it is not redeemed within a specified time, the shaft and land upon which it stands will pass out of the hands of the Field family and become the permanent possession of Rockland county. [...]

In April, 1882, the monument was blown to pieces by a charge of dynamite. In 1885 Mr. Field put up a larger and better stone and enclosed it with an iron fence. In the same year it was blown off its pedestal by another explosion. Public sentiment, however, began to change, and since the monument was replaced it has not been disturbed. [...]9

And another ninety-nine years later, that situation appears not to have changed, despite the urbanization that has taken place around it.

(Old Tappan is well worth a visit, for anyone travelling in the neighborhood. In addition to the André-related sites, it has a number of other historic buildings, and an interesting settlers' graveyard. It's probably a half-day expedition from New York City. (We drove up from Philadelphia, and managed to turn it into nearly a day-trip, but that was due to getting lost a few times.)

|

[Thanks to Holley Calmes for providing the photos of the interior of 76 House (which soundly defeated the flash on my digital camera).]

1 Benson Lossing, The Two Spies, Nathan Hale and John André (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1904), p105. [ back ]

2 Robert McConnel Hatch, Major John André, A Gallant in Spy's Clothing (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1986), photo insert. [ back ]

9 The Evening Bulletin, 7 November 1904. [ back ]

| Return to the Main Page | Last updated by the Webmaster on January 30, 2004 |