|

|

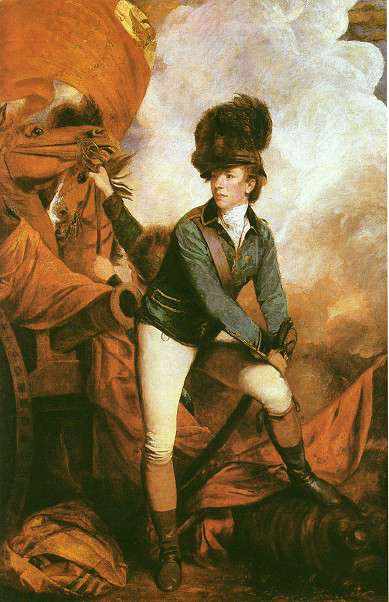

This famous portrait was painted shortly after Tarleton returned to England in 1782. It was commissioned by Mrs. Jane Tarleton, Banastre's mother, who took possession of it after its debut at the Royal Academy. It passed out of the Tarleton family in 1820, and was re-acquired by Admiral Sir John Tarleton in 1875. After that, it remained in the family until 1951, when Mrs. Henrietta Tarleton bequeathed it to the National Gallery in London, where it is currently on display.

|

Any portrait generates the question of whether or not it gives an accurate representation of the sitter's appearance. Portrait painters like Reynolds were the glamor photographers of their day, who knew how to show off any subject to his/her best, but practicality would have limited how far they could stretch the truth. It would have done their reputations no good to produce works that bore so little resemblance to the subject that they were laughable.

Unfortunately, very little in the way of contemporary verbal descriptions of Tarleton can be found for comparison. Shortly after his return home, Ruddiman's Weekly Mercury reported "Col. Tarleton appears to be about five and twenty, middle sized, and has a strong resemblance to the immortal Wolfe." (Balderdash. Ban's formidable schnozz fades to insignificance when compared to that awful accident with a pencil sharper of Wolfe's.) Major Thomas Young, a rebel who became Tarleton's prisoner after Cowpens, said, "He was a very fine looking man, with rather a proud bearing, but very gentlemanly in his manners." Beyond that, any physical descriptions I can locate don't describe Tarleton, they fairly obviously describe Tarleton as painted by Reynolds, which eliminates their usefulness.1

The painting was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1782, alongside another portrait (now lost) of Tarleton by Thomas Gainsborough. The Reynolds made far more of a hit, which is probably one of the reasons why the Gainsborough portrait (which, according to Bass, showed Tarleton mounted on a black charger) was never seen after its initial presentation, and was presumably destroyed or repainted.2

"Portrait of an Officer" was generally well received at its premier. In its coverage of the exhibit, the Morning Herald (May 2, 1782) said, "The portrait of Colonel Tarleton is a high-finished painting. The principal figure being finely disposed, and the ground and sky, described in a glow of colouring admirably suited to a martial subject." Even so, it didn't escape a satirical poke from "Peter Pindar":

Lo! TARLETON dragging on his boot so tight!

His Horses feel a godlike rage,

And yearn with Yankies to engage--

I think I hear them snorting for the fight!

Behold with fire each eyeball glowing!

I wish, indeed, their manes so flowing

Were more like hair: -- the brutes had been as good,

If, flaming with such classic force,

They had resembled less that horse

Call'd Trojan -- and by Greeks compos'd of wood.

I hate to disappoint those writers who see the pose as a pure and unadulterated expression of Ban's personal arrogance, but there is plentiful evidence that it was chosen by Reynolds. He had been planning to do something similar for some time, and was presumably only waiting for the arrival of the appropriate subject. When Ban swaggered through his door for a first sitting, the opportunity must have seemed obvious. The pose is based on an amalgamation of at least three classical sources: a pen sketch by Rembrandt which was in Reynolds' personal collection ("Tobias and the Angel at the River," c. 1652), Reynolds' own sketch of one of the figures in Tintoretto's "Ecce Homo" (done in 1752 when he was in Venice), and an antique marble sculpture of Hermes stooping to bind his sandal which is presently in the Louvre. (A cast of this sculpture was on display in the Royal Academy at the time Tarleton's portrait was painted.)

The uniform Tarleton wears in the painting is considered to be a generally accurate representation of the British Legion uniform (though the breeches should be doeskin or nankeen), but the background elements are pure fantasy. The "eagle" decoration on the banner is a meaningless artistic embellishment. (An equally meaningless "L." appears on the Smith mezzotint, and is often thought to be an afterthought by the engraver. However, I had a chance to view the original painting in June, 2001, and there are vague hints of an "L." on the banner which has faded over time. It would seem to be Reynolds' fancy, then, rather than Smith's.)

Unfortunately, Joshua Reynolds was fond of working with types of paint additives which do not age well (especially bitumen, which he felt gave his colors the "richness" of the Old Masters), with the result that the painting is already extensively cracked and is losing its color clarity.

A wealth of information on the painting from an artistic perspective, along with reproductions of all the various sources of inspiration for its design, can be found in Judy Egerton, The British School (London: National Gallery Publications, 1998) and J. Douglas Stuart, "Pigalle, the Antique et al.,; The Genesis of Reynolds' Banastre Tarleton" in Gazette des Beaux-Arts 112 (1988): 261-268.

A photo print/poster of the painting can be obtained through the Art Renewal Center.

| A detail of the portrait: | Mezzotint by John Raphael Smith: |

|

|

1 The Ruddiman's description is quoted Robert D. Bass, The Green Dragoon; The Lives of Banastre Tarleton and Mary Robinson (New York: Henry Holt and Company; 1957), p8. Thomas Young, "Memoir of Major Thomas Young," Orion Magazine, October/November, 1843, [pg unknown]. [ back ]

| Return to the Main Page | Last updated by the Webmaster on September 30, 2004 |