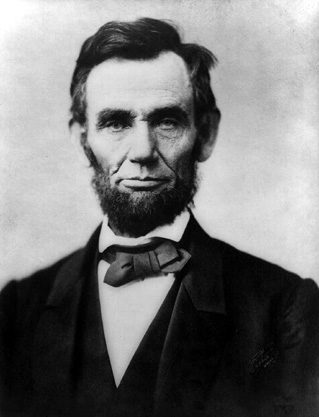

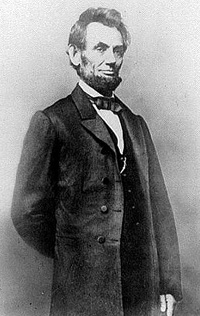

Lincoln rose from humble backwoods origins to become

one of the great presidents of the United States. In his effort

to preserve the Union during the Civil War, he assumed more power

than any preceding president. If necessity made him almost a

dictator, by fervent conviction he was always a democrat. A superb

politician, he persuaded the people with reasoned word and thoughtful

deed to look to him for leadership. He had a lasting influence

on American political institutions, most importantly in setting

the precedent of vigorous executive action in time of national

emergency.

Lincoln thought secession illegal, and was willing

to use force to defend Federal law and the Union. When Confederate

batteries fired on Fort Sumter and

forced its surrender, he called on the states for 75,000 volunteers.

Four more slave states joined the Confederacy but four remained

within the Union.

The Civil War had begun.

~ Early Years ~

The son of a Kentucky frontiersman, Lincoln had to

struggle for a living and for learning. Five months before receiving

his party's nomination for President, he sketched his life:

"I was born Feb. 12, 1809, in Hardin County,

Kentucky. My parents were both born in Virginia, of undistinguished

families--second families, perhaps I should say. My mother, who

died in my tenth year, was of a family of the name of Hanks....

My father ... removed from Kentucky to ... Indiana, in my eighth

year.... It was a wild region, with many bears and other wild

animals still in the woods. There I grew up.... Of course when

I came of age I did not know much. Still somehow, I could read,

write, and cipher ... but that was all."

|

Abraham Lincoln's ancestry on his father's side has been traced

to Samuel Lincoln, a weaver who emigrated from Hingham, England,

to Hingham, Massachusetts, in 1637. The president's forebears

were pioneers who moved west with the expanding frontier from

Massachusetts to Berks County, Pennsylvania, and then to Virginia.

Abraham's father, Thomas Lincoln, was born in Rockingham County

in backcountry Virginia in 1778. In 1781 Thomas Lincoln's father,

who was also named Abraham, took his family to Hughes Station

on the Green River, 32 km (20 mi) east of Louisville, Kentucky.

In 1786 an Indian (Native American) killed the first Abraham

Lincoln while he was at work clearing land for a farm in the

forest. |

|

Thomas Lincoln continued to live in Kentucky. He saw

it develop from a frontier wilderness into a rapidly growing

state. But like his ancestors he preferred the rugged life on

the frontier. In a brief autobiography written for a political

campaign, Lincoln said that his father "even in childhood

was a wandering labor boy, and grew up literally without education.

He never did more in the way of writing than to bunglingly sign

his own name."

Despite Thomas Lincoln's apparent shiftlessness, he became a

skilled carpenter, and he never lacked the basic necessities

of life. At one time he owned title to two farms. He always possessed

one or more horses. He paid his taxes, and, like his neighbors,

he accepted jury duty and militia duty when called.

On June 12, 1806, Thomas Lincoln married Nancy Hanks. Little

is known about Abe Lincoln's mother except that she came from

a very poor Virginia family. She was completely illiterate and

signed her name with an X. After their marriage the Lincolns

moved from a farm on Mill Creek in Hardin County, Kentucky, to

nearby Elizabethtown. There Thomas Lincoln earned his living

as a carpenter and handyman. In 1807 a daughter, Sarah, was born.

In December 1808 the Lincolns moved to a 141-hectare (348-acre)

farm on the south fork of Nolin Creek near what is now Hodgenville,

Kentucky. On February 12, 1809, in a log cabin that Thomas Lincoln

had built, a son, Abraham, was born. Later the Lincolns had a

second son who died in infancy.

When Abraham Lincoln was two, the family moved to another farm

on nearby Knob Creek. Life was lonely and hard. There was little

time for play. Most of the day was spent hunting, farming, fishing,

and doing chores. Land titles in Kentucky were confused and often

subject to dispute. Thomas Lincoln lost his title to the Mill

Creek farm, and his claims to both the Nolin Creek and Knob Creek

tracts were challenged in court. In 1816, therefore, the Lincolns

decided to move to Indiana, where the land was surveyed and sold

by the federal government. |

|

In the winter of 1816 the Lincolns took their meager possessions,

ferried across the Ohio River, and settled near Pigeon Creek,

close to what is now Gentryville, Indiana. Because it was winter,

Thomas Lincoln immediately built a crude, three-sided shelter

that served as home until he could build a log cabin. A fire

at the open end of the shelter kept the family warm. At this

time southern Indiana was a heavily forested wilderness. Lincoln

described it as a "wild region, with many bears and other

wild animals in the woods." Later some of Nancy Hanks's

relatives moved near the site the Lincolns had chosen, and a

thriving frontier community gradually developed.

In 1818 an epidemic of the milk sick broke out. This was not

actually a disease. It was caused by drinking poisoned milk from

cows that had eaten the wild snakeroot plant. One of the first

victims of the milk sick was Nancy Hanks Lincoln. She died October

5, 1818. The next year, Thomas Lincoln journeyed to Elizabethtown,

Kentucky, and married Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow with three

children. Abe Lincoln was very much attached to his kind stepmother,

and he later referred to her as "my angel mother."

One of the most important jobs on a frontier farm

was clearing the forest. Young Abe Lincoln quickly became skilled

with an axe. In his autobiographical sketch written in the third

person, Lincoln stated that "the clearing away of surplus

wood was the great task ahead. Abraham, though very young, was

large for his age, and had an axe put in his hands at once. From

that till within his twenty-third year, he was almost constantly

handling that most useful instrument." One of his chores

with an axe was to make fence rails by splitting poles. Later,

as a presidential candidate, Lincoln was known as the "Railsplitter."

~ Education ~

When his father could spare him from chores, Lincoln

attended an ABC school. Such schools were held in log cabins,

and often the teachers were barely more educated than their pupils.

According to Lincoln, "no qualification was ever required

of a teacher beyond readin', writin', and cipherin', to the Rule

of Three." Including a few weeks at a similar school in

Kentucky, Lincoln had less than one full year of formal education

in his entire life.

Abe's stepmother encouraged his quest for knowledge.

At an early age he could read, write, and do simple arithmetic.

Books were scarce on the Indiana frontier, but besides the family

Bible, which Lincoln knew well, he was able to read the classical

authors Aesop, John Bunyan, and Daniel Defoe, as well as William

Grimshaw's History of the United States (1820) and Mason

Locke Weems's Life and Memorable Actions of George Washington

(about 1800). This biography of George Washington made a lasting

impression on Lincoln, and he made the ideals of Washington and

the founding fathers of the United States his own.

By the time Lincoln was 19 years old, he had reached his full

height of 1.93 m (6 ft 4 in). He was lean and muscular, with

long arms and big hands that gave him an awkward appearance.

Although he had remarkable strength, he never liked farm work.

He preferred instead the easy congeniality that he found at the

general store in nearby Gentryville. A neighbor recalled "Abe

was awful lazy, he would laugh and talk and crack jokes and tell

stories all the time."

The Pigeon Creek farm was near the Ohio River, and Lincoln often

earned money ferrying passengers and baggage to riverboats waiting

in midstream. In 1828, when he was 19, he was hired by the local

merchant, James Gentry, to take a cargo-laden flatboat down the

Mississippi River to New Orleans. |

|

~ Illinois ~

In 1830 another epidemic of milk sick was rumored

to be breaking out in Indiana. Already the Hanks family had moved

west to Illinois, and their enthusiastic letters describing their

new home rekindled the pioneering spirit in Thomas Lincoln. In

March 1830 the Lincoln family set out for the Illinois country.

They settled at the junction of woodland and prairie on the north

bank of the Sangamon River, 16 km (10 mi) west of what is now

Decatur, Illinois. Lincoln helped his father build a log cabin

and fence in 4 hectares (10 acres) to grow corn. Then he hired

out to neighbors, helping them to split rails. That year, Lincoln

attended a political rally and was persuaded to speak on behalf

of a local candidate. It was his first political speech. A witness

recalled that Lincoln "was frightened but got warmed up

and made the best speech of the day."

In 1831 Lincoln made a second trip to New Orleans.

He was hired, along with his stepbrother and a cousin, by Denton

Offutt, a Kentucky trader and speculator, to build a flatboat

and take it down the Mississippi with a load of cargo. The pay

was 50 cents a day plus a fee of $60. According to legend, Lincoln

saw his first slave auction in New Orleans and said, "If

I ever get a chance to hit that thing, I'll hit it hard."

~ Early Political Career

~

In the spring of 1832, Lincoln decided to run for

a seat in the Illinois house of representatives. This was a logical

step for Lincoln to take, for on the frontier a young man with

ability and ambition could rise rapidly in politics.

|

A month after Lincoln announced his candidacy, Offutt's general

store went bankrupt and Lincoln found himself without a job.

But almost immediately, Governor John Reynolds of Illinois called

for volunteers to put down a rebellion of the Native American

Sauk (or Sac) and Fox peoples led by Chief Black Hawk. Lincoln

enlisted at once and, because of his popularity, was elected

captain of his company. When his term expired, he reenlisted

as a private. In all, he served three months, but saw no actual

fighting. However, Lincoln took great pride in this brief military

career. |

|

~ First Campaign ~

When Lincoln returned to New Salem in 1832, election

day was two weeks away. It was a presidential election year,

and political parties had formed around the contending candidates.

Followers of Andrew Jackson, who was seeking a second term as

president, called themselves Democrats. Followers of U.S. Senator

Henry Clay of Kentucky called themselves National Republicans

and later Whigs. Lincoln supported Clay, who had long been his

political idol. He remained a faithful Whig until the party disintegrated

over the question of slavery in the 1850s.

Lincoln's program, as published in the Sangamon, Illinois, Journal,

called for the construction of canals and roads, better schools,

and a low interest rate to stimulate local economic growth. In

his brief campaign, Lincoln spoke from tree stumps in village

squares, visited farmers in their homes and fields, and shook

hands and exchanged stories with as many people as he could meet.

Nevertheless, he was defeated. There were 13 county candidates

running for four legislative seats. Lincoln finished eighth.

In his own precinct, however, he got 277 out of 300 votes even

though the precinct voted overwhelmingly to support the Democrat,

Jackson, for the presidency.

~ Postmaster ~

After his defeat, Lincoln opened a general store in

New Salem with William F. Berry as his partner. But Berry misused

the profits, and in a few months the venture failed. Berry died

in 1835, leaving Lincoln responsible for debts amounting to $1100.

It took him several years to pay them off.

|

After the general store failed, Lincoln was appointed postmaster

of New Salem. The appointment came from Jackson's Democratic

administration. Lincoln's Whig views were well known, but, as

Lincoln explained it, the postmaster's job was "too insignificant

to make his politics an objection." As postmaster, Lincoln

earned $60 a year plus a percentage of the receipts on postage.

He ran an informal post office, often doing favors for friends,

such as undercharging them for mailing letters. The job gave

him time to read, and he made a habit of reading all the newspapers

that came through the office. To augment his income, he became

the deputy surveyor of Sangamon County. |

|

~ Illinois Legislator ~

In 1834 Lincoln again ran for representative to the

Illinois legislature. By then he was known throughout the county,

and many Democrats gave him their votes. He was elected in 1834

and reelected in 1836, 1838, and 1840. As a member of the Whig

minority he became the protégé of the Whig floor

leader, Representative John T. Stuart of Springfield. When Stuart

ran for a seat in the Congress of the United States in 1836,

Lincoln replaced him as floor leader. Stuart also encouraged

Lincoln to study law, which Lincoln did between legislative sessions.

Lincoln's main achievement as a state legislator was the transfer

of the state capital from Vandalia to Springfield. In this effort

he acted as the leader of Sangamon County's delegation of seven

representatives and two state senators, a group called the Long

Nine because they were all tall men. Lincoln devised a strategy

whereby the Sangamon delegation supported the projects of other

legislators in return for their support of Springfield as the

capital city. In American politics this kind of aid is called

logrolling, a term derived from frontier families' tradition

of helping each other to build log cabins.

Lincoln's other votes in the state legislature reflected his

Whig background. He supported the business interests in the state

and defended the pro-business national platform of Henry Clay.

Lincoln's experience in the Illinois legislature sharpened his

political skills. He was adept at logrolling, skilled in debate,

and expert in the art of political maneuver.

In 1837 Lincoln took his first public stand on slavery when the

Illinois legislature voted to condemn the activities of the abolition

societies that wanted an immediate end to slavery by any means.

Lincoln and a colleague declared that slavery was "founded

on both injustice and bad politics, but the promulgation of abolitionist

doctrine tends rather to increase than abate its evil."

Lincoln was against slavery, but he favored lawful means of achieving

its destruction. Throughout his political career, Lincoln avoided

extreme abolitionist groups.

~ Early Law Practice ~

Meanwhile, Lincoln continued his study of law, and in 1836 he

became a licensed attorney. The following year he became a junior

partner in John T. Stuart's law firm and moved from New Salem

to Springfield. Lincoln was extremely poor and arrived in Springfield

on a borrowed horse with all his belongings in two saddlebags.

A Springfield storekeeper, Joshua Fry Speed, whom Lincoln later

called "my most intimate friend," gave Lincoln free

lodging.

~ Courtship and Marriage

~

According to a now discredited legend, while in New

Salem, Lincoln was said to have been in love with Ann Rutledge,

the beautiful young daughter of a local innkeeper. When she died

in 1835, Lincoln was said to be "plunged in despair."

The frequent lapses into melancholy that marked his adult years

were said to be a result of this tragic death. But Lincoln in

his later years never referred to Ann Rutledge, and authorities

are unanimous in agreeing that the Lincoln-Rutledge romance is

a myth.

Indeed, less than 18 months after Ann's death, Lincoln proposed

marriage to Mary Owens, a Kentucky girl who also lived in New

Salem. Theirs was not an ardent love affair, but having made

his proposal, Lincoln felt he could not honorably break it off.

Much to his relief, Mary turned him down. Later she explained,

"I thought Mr. Lincoln was deficient in those little links

which make up the chain of a woman's happiness."

|

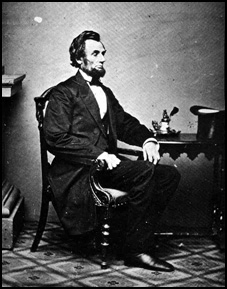

In 1840, Lincoln met a cultured, high-strung Kentucky woman

named Mary Todd (right), who was

staying with a married sister in Springfield. After a long courtship,

they were married on November 4, 1842. A week later, Lincoln

wrote a fellow lawyer, "Nothing new here, except my marrying,

which to me, is a matter of profound wonder." |

|

|

Late in 1843 the Lincolns moved from their simple rented

quarters to a modest frame house in Springfield that Lincoln

bought for $1500. Of their four boys, only the eldest, Robert

Todd Lincoln (right), reached adulthood.

He was born in 1843 and died in 1926. Edward Baker Lincoln was

born in 1846 and died at the age of four. |

|

|

William Wallace (right),

called Willie, was born in 1850 and died in the White House,

the presidential mansion, shortly before his 12th birthday. Lincoln's

favorite son, Thomas, whom he affectionately called Tad (left), was born in 1853, grew up in

the White House, and died at the age of 18. |

|

|

In contrast with the sweet, loving Ann Rutledge of legend, Mary

Todd Lincoln has unfairly been pictured as a shrew who made Lincoln's

life miserable. Certainly she was spoiled, haughty, and temperamental.

The death of her children caused her much anguish, and after

Willie's death she was often hysterical. Lincoln was devoted

to her, however, and there is no evidence that theirs was not

a happy marriage. |

|

On those occasions when she became upset, Lincoln

treated her with patience and understanding. He, for his part,

was careless in his personal habits and subject to extreme depression.

What he and his wife had in common was ambition. Mary aided her

husband's political career immeasurably.

~ Frontier Lawyer ~

At the time of his marriage, Lincoln was earning $1200

to $1500 a year from his law practice, a good income for the

time and place. When the law firm of Stuart and Lincoln dissolved

in 1841, Stephen T. Logan, an able and experienced lawyer, took

Lincoln in as junior partner. In 1844 the firm of Logan and Lincoln

also dissolved, and Lincoln formed a lifelong partnership with

a young lawyer named William H. Herndon.

Lawsuits on the Illinois frontier usually dealt with such trivial

matters as crop damage caused by wandering livestock, ownership

of hogs and horses, small debts, libel, and assault and battery.

The Springfield courts were in session only a small part of the

year. For three months each spring and fall, lawyers and judges

rode the circuit, holding court at rural county seats. Lincoln

rode the eighth judicial circuit, the largest in the state, covering

15 counties and about 12,900 sq km (about 8000 sq mi).

The local sessions of the circuit court were major events on

the frontier. The particulars of each case were well known to

the townspeople and were subject to heated debate. Courtroom

conduct was informal, and more often than not a case was won

on a lawyer's speaking ability rather than the legal merits of

his case. The judge and the lawyers were treated as celebrities,

and Lincoln, because of his storytelling abilities and skill

as a lawyer, was popular on the circuit. Ever the politician,

he used this opportunity to meet new people and advance his political

career.

Lincoln still had political ambitions, but he now looked beyond

the statehouse to the U.S. Congress. In 1843 he wrote a fellow

politician, "Now if you should hear any one say that Lincoln

don't want to go to Congress, I wish you as a personal friend

of mine, would tell him you have reason to believe he is mistaken.

The truth is, I would like to go very much."

The Whigs were a minority party in Illinois, and there was competition

among the Whig politicians over the nomination for U.S. representative

for the Seventh Congressional District, where Whigs were in the

majority. Lincoln sought the nomination in 1842 and 1844 and

received it in 1846. He went on to defeat the Democratic candidate,

the Methodist preacher Peter Cartwright, in the election of November

1846.

~ United States Congressman

~

Congressman-elect Lincoln was a popular, masterful

politician in Illinois. Having succeeded in the rough-hewn Illinois

legislature, he was confident that he would make his mark in

Congress. Once in Washington, D.C., however, Lincoln became one

of many unknown freshman congressmen. The inner councils of government

were closed to him, as was the Washington social life that Mary

Lincoln was looking forward to. However, Lincoln never lost confidence

in himself. He wrote Herndon, "As you are all so anxious

for me to distinguish myself, I have concluded to do so before

long." The Lincolns, with their two sons, lived quietly

in a modest boardinghouse. Lincoln had a small body of friends

with whom he could relax and discuss politics. Among them was

Alexander H. Stephens, the Whig congressman from Georgia, who

later became vice president of the Confederate States of America.

~ Antislavery Leader ~

Lincoln was losing interest in politics when, in 1854,

Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act. The act aroused Lincoln,

in his words, "as he had never been before." The act

created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, and stated that

each territory could be admitted as a state "with or without

slavery, as their constitution may prescribe at the time of their

admission." The author of the act, Senator Stephen A. Douglas,

the leading Democrat of Illinois, called this program popular

sovereignty because it allowed the voters in these territories

to decide for themselves whether slavery would be allowed. The

Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the old dividing line between free

and slave states as set by the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, a new Lincoln emerged

into the world of politics. Although he was as ambitious for

political office as ever, he was now, for the first time in his

career, devoted to a cause. He became a forceful spokesman for

the antislavery forces.

~ Candidate for United States

Senate ~

Agitation over the slavery issue increased in 1856

and 1857. In the Dred Scott Case the U.S. Supreme Court ruled

that Congress could not prohibit slavery in the territories.

In Kansas proslavery and antislavery partisans were engaged in

a bloody civil war for control of the territorial government.

Northern abolitionists demanded the immediate destruction of

slavery, while Southern apologists insisted that their "peculiar

institution" was beneficial to both slaveowner and slave.

In 1858 Senator Douglas came up for reelection. The Republican

Party nominated Lincoln to oppose him. In his acceptance speech

before the Republican state convention in Springfield, Lincoln

said, "A house divided against itself cannot stand. I believe

this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half

free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved; I do not expect

the house to fall; but I do expect it will cease to be divided.

It will become all one thing, or all the other." This was

Lincoln's most extreme statement against slavery. Although he

returned to his more moderate position as expressed in the Peoria

speech, his opponents used the militant words of the House Divided

speech against him.

~ Lincoln-Douglas Debates

~

Both Lincoln and Douglas were excellent speakers.

When Douglas was told that Lincoln was his opponent, he said,

"I shall have my hands full. He is the strong man of the

party-full of wit, facts, dates-and the best stump speaker, with

his droll ways and dry jokes, in the West."

|

The campaign opened in Chicago. Douglas defended popular sovereignty

and attacked Lincoln for his "house divided" speech.

He accused Lincoln of trying to divide the nation. Lincoln replied

by calling for national unity. Recalling the Declaration of Independence,

the document on which the United States was founded, he said,

"Let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the

other man-this race and that race and the other race, being inferior,

and therefore they must be placed in an inferior position. Let

us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout

the land, until we shall once more stand up declaring that all

men are created equal." |

|

In July, Lincoln challenged Douglas to a series of face-to-face

debates. Douglas accepted. It was arranged that seven three-hour

debates would be held in seven different cities between August

and October. In the debates, both candidates respected each other

and kept to the issues. The crux of the discussion was the morality

of slavery.

The debates captivated Illinois. About 10,000 people listened

to the first debate under a blazing hot sun at Ottawa. Over 15,000

listened in drizzling rain at Freeport. Even in the small towns

where the candidates spoke alone, crowds of as many as 6000 were

common. The newspapers carried the arguments of each candidate

throughout the nation.

The Lincoln-Douglas debates brought Lincoln national recognition.

He accepted invitations to speak in Ohio, Indiana, Kansas, Iowa,

Wisconsin, and at the Cooper Union college in New York City.

~ PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED

STATES ~

First Year in Office

Even before election day, Southern militants were

threatening to secede from the Union if Lincoln was elected.

In December, with the Republican victory final, South Carolina

seceded. By February, Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia,

Louisiana, and Texas had followed. These states joined together

to form the Confederate States of America,

also known as the Confederacy. President

Buchanan did nothing to stop the secessionist movement, and

President-elect Lincoln was not yet in a position to intercede.

Lincoln remained silent on the issue, believing that, in time,

Union sentiment would reassert itself in the South and the secession

of the seven states would come to an end.

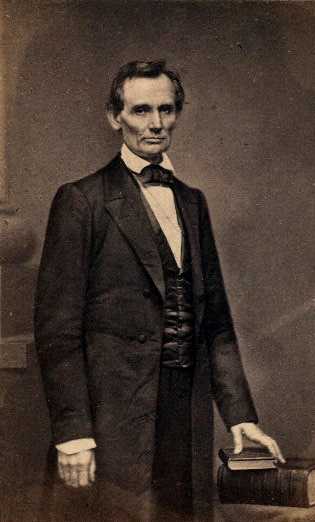

On February 11, 1861, Lincoln bade farewell to his neighbors

in Springfield and set out for Washington, D.C. He now had a

beard, which he had grown at the suggestion of a young girl during

the campaign. Alluding to the troubled days ahead, he told his

friends, "Today I leave you; I go to assume a task more

difficult than that which devolved upon General Washington. Unless

the great God who assisted him, shall be with and aid me, I must

fail. But if the same omniscient mind, and almighty arm that

directed and protected him, shall guide and support me, I shall

not fail, I shall succeed. Let us all pray that the God of our

fathers may not forsake us now."

On the way to Washington, Lincoln made many short speeches, but

he did not commit himself to a specific policy regarding the

South. Because of a rumor of an assassination plot against him

in Baltimore, he was secretly spirited through that city and

into Washington by night. The opposition press ridiculed this

undignified entry of the president-elect into the capital.

~ The Civil War ~

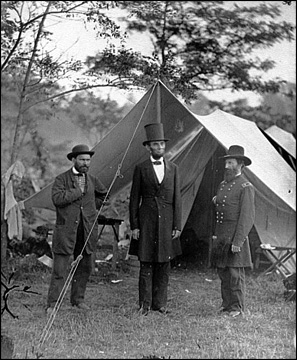

As a commander in chief Lincoln was soon noted for

vigorous measures, sometimes at odds with the Constitution and

often at odds with the ideas of his military commanders. After

a period of initial support and enthusiasm for George

B. McClellan, Lincoln's conflicts with that Democratic general

helped to turn the latter into his presidential rival in 1864.

Famed for his clemency for court-martialed soldiers, Lincoln

nevertheless took a realistic view of war as best prosecuted

by killing the enemy. Above all, he always sought a general,

no matter what his politics, who would fight. He found such a

general in Ulysses S. Grant, to whom he gave overall command

in 1864. Thereafter, Lincoln took a less direct role in military

planning, but his interest never wavered, and he died with a

copy of Gen. William Sherman's orders for the March to the Sea

in his pocket.

|

Politics vied with war as Lincoln's major preoccupation in the

presidency. The war required the deployment of huge numbers of

men and quantities of materiel; for administrative assistance,

therefore, Lincoln turned to the only large organization available

for his use, the Republican party. With some rare but important

exceptions (for example, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton),

Republicans received the bulk of the civilian appointments from

the cabinet to the local post offices. Lincoln tried throughout

the war to keep the Republican party together and never consistently

favored one faction in the party over another. Military appointments

were divided between Republicans and Democrats. |

|

Democrats accused Lincoln of being a tyrant because he proscribed

civil liberties. For example, he suspended the writ of habeas

corpus in some areas as early as Apr. 27, 1861, and throughout

the nation on Sept. 24, 1862, and the administration made over

13,000 arbitrary arrests. On the other hand, Lincoln tolerated

virulent criticism from the press and politicians, often restrained

his commanders from overzealous arrests, and showed no real tendencies

toward becoming a dictator. There was never a hint that Lincoln

might postpone the election of 1864, although he feared in August

of that year that he would surely lose to McClellan. Democrats

exaggerated Lincoln's suppression of civil liberties, in part

because wartime prosperity robbed them of economic issues and

in part because Lincoln handled the slavery issue so skillfully.

The Constitution protected slavery

in peace, but in war, Lincoln came to believe, the commander

in chief could abolish slavery as a military necessity. The preliminary

Emancipation Proclamation of Sept. 22, 1862, bore this military

justification, as did all of Lincoln's racial measures, including

especially his decision in the final proclamation of Jan. 1,

1863, to accept blacks in the army. By 1864, Democrats and Republicans

differed clearly in their platforms on the race issue: Lincoln's

endorsed the 13th Amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery,

whereas McClellan's pledged to return to the South the rights

it had had in 1860.

|

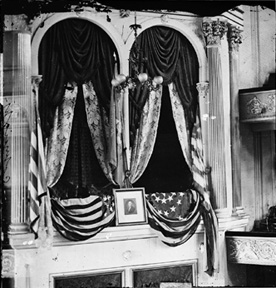

Lincoln's victory in that election thus changed the racial

future of the United States. It also agitated Southern-sympathizer

and Negrophobe John Wilkes Booth , who

began to conspire first to abduct Lincoln and later to kill him.

On Apr. 14, 1865, five days after Robert E. Lee's surrender to

Grant at Appomattox Court House, Lincoln attended a performance

of Our American Cousin at Ford's Theatre in Washington.

There Booth entered the presidential box and shot Lincoln.

The next morning at 7:22 Lincoln died

President's box seats at Ford's

Theater (left) |

|

Lincoln never let the world forget that the Civil

War involved an even larger issue. This he stated most movingly

in dedicating the military cemetery at Gettysburg: "that

we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in

vain--that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of

freedom--and that government of the people, by the people, for

the people, shall not perish from the earth."

Click here to go to Lincoln's "Gettysburg

Address"

Lincoln won re-election in 1864, as Union military

triumphs heralded an end to the war. In his planning for peace,

the President was flexible and generous, encouraging Southerners

to lay down their arms and join speedily in reunion.

The spirit that guided him was clearly that of his

Second Inaugural Address, now inscribed on one wall of the Lincoln

Memorial in Washington, D. C.: "With malice toward none;

with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives

us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are

in; to bind up the nation's wounds.... "

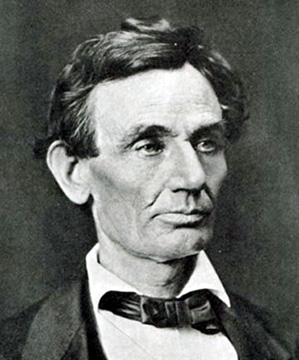

Of all the American presidents, Lincoln is probably the one about

whom the most has been written.

Many critical evaluations of his life have been published, but

they have not diminished his stature, and he remains one of the

foremost products of American democracy and an eloquent spokesman

for its ideals. |

|

|

![]()