~ The Reason We Went to War

~

~ The Reason We Went to War

~

Close to two million slaves were brought to the American

South from Africa and the West Indies during the centuries of

the Atlantic slave trade. Approximately 20% of the population

of the American South over the years has been African American,

and as late as 1900, 9 out of every 10 African Americans lived

in the South. The large number of black people maintained as

a labor force in the post-slavery South were not permitted to

threaten the region's character as a white man's country, however.

The region's ruling class dedicated itself to the overriding

principle of white supremacy, and white racism became the driving

force of southern race relations. The culture of racism sanctioned

and supported the whole range of discrimination that has characterized

white supremacy in its successive stages. During and after the

slavery era, the culture of white racism sanctioned not only

official systems of discrimination but a complex code of speech,

behavior, and social practices designed to make white supremacy

seem not only legitimate but natural and inevitable.

In the antebellum South, slavery provided the economic

foundation that supported the dominant planter ruling class.

Under slavery the structure of white supremacy was hierarchical

and patriarchal, resting on male privilege and masculinist honor,

entrenched economic power, and raw force. Black people necessarily

developed their sense of identity, family relations, communal

values, religion, and to an impressive extent their cultural

autonomy by exploiting contradictions and opportunities within

a complex fabric of paternalistic give-and-take. The working

relationships and sometimes tacit expectations and obligations

between slave and slave holder made possible a functional, and

in some cases highly profitable, economic system.

--

Academic Affairs Library, The

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill |

~ Beginnings ~

|

Slavery played a central role in the history

of the United States. It existed in all the English mainland

colonies and came to dominate agricultural production in the

states from Maryland south. Eight of the first 12 presidents

of the United States were slave owners. Debate over slavery increasingly

dominated American politics, leading eventually to the American

Civil War, which finally brought slavery to an end. After emancipation,

overcoming slavery's legacy remained a crucial issue in American

history, from Reconstruction following the war, to the civil

rights movement a century later.

Slavery has appeared throughout history in many forms

and many places. Slaves have served in capacities as diverse

as concubines, warriors, servants, craft workers, and tutors.

In the Americas, however, slavery emerged as a system of forced

labor designed for the production of staple crops. Depending

on location, these crops included sugar, tobacco, coffee, and

cotton; in the southern United States,

by far the most important staples were tobacco and cotton. |

|

Most of the agriculture in the southern United States during

the early 19th century was dedicated to growing one crop-cotton.

Most of the cotton crop was grown on large plantations that used

black slave labor, such as this one on the Mississippi River. |

|

|

There was nothing inevitable about the use of black

slaves. Although 20 Africans were purchased in Jamestown, Virginia,

as early as 1619, throughout most of the 17th century the number

of Africans in the English mainland colonies (American Colonies)

grew slowly. During those years, colonists experimented with

two other sources of forced labor: Native American slaves and

European indentured servants. The number of Native American slaves

was limited in part because the Native Americans were in their

homeland; they knew the terrain and could escape fairly easily.

Although some Native American slaves existed in every colony

the number was limited. The settlers found it easier to sell

Native Americans captured in war to planters in the Caribbean

than to turn them into slaves on their own terrain.

More important as a form of labor was indentured servitude.

Most indentured servants were poor Europeans who wanted to escape

harsh conditions and take advantage of opportunities in America.

They traded four to seven years of their labor in exchange for

the transatlantic passage. At first, indentured servants came

mainly from England, but later they came increasingly from Ireland,

Wales, and Germany. They were primarily, although not exclusively,

young males. Once in the colonies, they were essentially temporary

slaves; most served as agricultural workers although some, especially

in the North, were taught skilled trades. During the 17th century,

they performed most of the heavy labor in the Southern colonies

and also provided the bulk of immigrants to those colonies. |

|

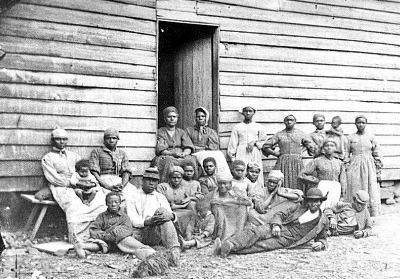

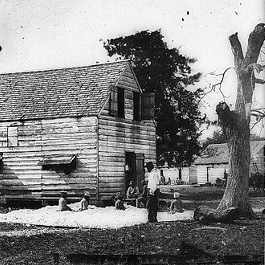

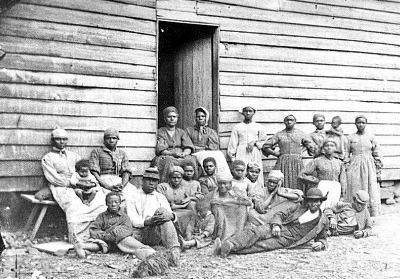

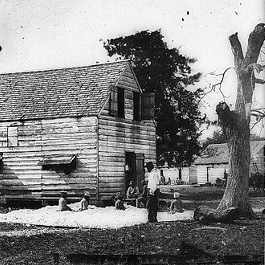

Ex-slaves sitting in front of a cabin. This picture is from the

main eastern theater of war, The Peninsular Campaign, May-August

1862. |

|

~ Slave Trade ~

|

Because the labor needs of the rapidly growing colonies

were increasing, this decline in servant migration produced a

labor crisis. To meet it, landowners turned to African slaves,

who from the 1680s began to replace indentured servants; in Virginia,

for example, blacks, the great majority of whom were slaves,

increased from about 7 percent of the population in 1680 to more

than 40 percent by the mid-18th century. During the first half

of the 17th century, the Netherlands and Portugal had dominated

the African slave trade and the number of Africans available

to English colonists was limited because the three countries

competed for slave labor to produce crops in their American colonies.

During the late 17th and 18th centuries, by contrast, naval superiority

gave England a dominant position in the slave trade, and English

traders transported millions of Africans across the Atlantic

Ocean.

Since others died before boarding the ships, Africa's

loss of population was even greater. By far the largest importers

of slaves were Brazil and the Caribbean colonies; together, they

received more than three-quarters of all Africans brought to

the Americas. About 6 percent of the total (600,000 to 650,000

people) came to what is now the United States. |

|

The transatlantic slave trade produced one of

the largest forced migrations in history. From the early 16th

to the mid-19th centuries, between 10 million and 11 million

Africans were taken from their homes, herded onto ships where

they were sometimes so tightly packed that they could barely

move, and sent to a strange new land. |

|

~ Spread of Slavery ~

|

Slavery spread quickly in the American colonies. At first the

legal status of Africans in America was poorly defined, and some,

like European indentured servants, managed to become free after

several years of service. From the 1660s, however, the colonies

began enacting laws that defined and regulated slave relations.

Central to these laws was the provision that black slaves, and

the children of slave women, would serve for life. By the 1770s,

slaves constituted about 40 percent of the population of the

Southern colonies, with the highest concentration in South Carolina,

where more than half the people were slaves. |

|

|

Slaves performed numerous tasks, from clearing

forests to serving as guides, trappers, craft workers, nurses,

and house servants, but they were most essential as agricultural

laborers. Slaves were most numerous where landowners sought to

grow staple crops for market, such as tobacco in the upper South

(Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina) and rice in the lower South

(South Carolina, Georgia). Slaves also worked on large wheat-producing

estates in New York and on horse-breeding farms in Rhode Island,

but climate and soil restricted the development of commercial

agriculture in the Northern colonies, and slavery never became

as economically important as it did in the South. Slaves in the

North were typically held in small numbers, and most served as

domestic servants. Only in New York did they form more than 10

percent of the population, and in the North as a whole less than

5 percent of the inhabitants were slaves.

~ Slavery in the US ~

By the mid-18th century, American slavery had acquired

a number of distinctive features. More than 90 percent of American

slaves lived in the South where conditions contrasted sharply

with those to both the south and north. In Caribbean colonies,

such as Jamaica and Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti), blacks

outnumbered whites by more than ten to one and slaves often lived

on huge estates with hundreds of other slaves. In the Northern

colonies, blacks were few and slaves were typically held in small

groups of less than five. The South, by contrast, was neither

overwhelmingly white nor overwhelmingly black: slaves formed

a large minority of the population, and most slaves lived on

small and medium-sized holdings containing between 5 and 50 slaves.

The second distinctive characteristic of slavery in

the United States was in many ways the most important: in contrast

to slaves in most other parts of the Americas, those in the United

States experienced natural population growth. Elsewhere,

in regions as diverse as Brazil, Jamaica, Saint-Domingue, and

Cuba, slave mortality rates exceeded birth rates, and growth

of the slave population depended on the importation of new slaves

from Africa. As soon as that importation ended, the slave population

began to decline. At first, deaths among slaves also exceeded

births in the American colonies, but in the 18th century the

birth rates rose in those colonies, mortality rates fell, and

the slave population became self-reproducing. This transition,

which occurred earlier in the upper than in the lower South,

meant that even after slave imports were outlawed in 1808, the

number of slaves continued to grow rapidly. During the next 50

years, the slave population of the United States more than

tripled, from about 1.2 million to almost 4 million in 1860.

The natural growth of the slave population meant that slavery

could survive without new slave imports.

By the 1770s, only about 20 percent of slaves in the

colonies were African-born, although the concentration of Africans

remained higher in South Carolina and Georgia. After 1808 the

proportion of African-born slaves became tiny.

The emergence of a native-born slave population had

numerous important consequences. For example, among African-born

slaves, who were imported for their ability to perform physical

labor, there were few children and men outnumbered women by about

two to one. In contrast, American-born slaves began their slave

careers as children and included approximately even numbers of

males and females. Masters went through a similar process of

Americanization. Those born in America usually felt at

home on their holdings. Caribbean planters often sought to make

their fortunes quickly and then retire to a life of leisure in

England. American slave holders, by contrast, were less often

absentee owners. Instead, they typically took an active role

in running their farms and plantations. |

|

Seven African American slaves sitting in a pile of cotton in

front of a gin house on the Smith Plantation, 1861-1862). |

|

~ Beginnings of the Opposition

to Slavery ~

The last third of the 18th century saw the first widespread

questioning of slavery by white Americans. This questioning increased

after the American Revolution (1775-1783), which sharply increased

egalitarian thinking. The contradiction between the rhetoric

of documents such as the Declaration of Independence and the

reality of slavery was apparent. Many leaders of the new government,

including George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, while slave

holders, were profoundly troubled by slavery. Although leery

of rash actions, they undertook a series of cautious acts that

they thought would lead to gradual abolition of slavery.

These acts included measures in all states north of Delaware

to abolish slavery. A few states did away with slavery immediately.

More typical were gradual emancipation acts, such as that passed

by Pennsylvania in 1780, whereby all children born to slaves

in the future would be freed when they became 28 years old. Two

significant measures dated from 1787. First, the Northwest

Ordinance barred slavery from the Northwest Territory, an

area that included much of what is now the upper Midwest. Second,

a compromise reached at the Constitutional Convention allowed

the Congress of the United States to outlaw the importation

of slaves in 1808. Meanwhile, a number of states passed acts

making it easier for individuals to free their slaves.

Hundreds of slave owners, especially in the upper

South, set some or all of their slaves free. In addition, tens

of thousands of slaves acted on their own, taking advantage of

wartime disruption to escape from their masters. As a result,

the number of free blacks, which had been tiny before the Revolution,

surged during the last quarter of the 18th century.

Nevertheless, the Revolutionary-era challenge to slavery

was successful only in the North, where the investment in slaves

was small. The antislavery movement never made much progress

in Georgia and South Carolina, where planters imported tens of

thousands of Africans to beat the cut-off of the slave trade

in 1808. In the upper South, sentiment in favor of equality faded,

along with revolutionary enthusiasm, in the 1790s and 1800s.

The end of slave imports did not undermine slavery as it did

elsewhere because the slave population in the United States was

self-reproducing. The ultimate result of the first antislavery

movement was to leave slavery a newly sectional institution,

on the road to abolition throughout the North but largely intact

in the South. |

~ Growth of Slavery ~

|

Slavery expanded rapidly, along with the United States.

Fueled by a surging world demand for cotton and the 1793 invention

of the cotton gin, which efficiently separated the cotton seeds

from the fiber, cotton cultivation spread rapidly westward.

By the 1830s, Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana

formed the heart of a new cotton kingdom, producing more than

half of the nation's supply of the crop. The great bulk of this

cotton was cultivated by slaves. Between 1790 and 1860, about

one million slaves were moved west, almost twice the number of

Africans shipped to the United States during the whole period

of the transatlantic slave trade. Some slaves moved with their

masters and others moved as part of a new domestic trade in which

owners from the seaboard states sold slaves to planters in the

cotton-growing states of the new Southwest.

As slavery grew, so too did its diversity. Slavery

varied according to region, crops, and size of holdings. On farms

and small plantations most slaves came in frequent contact with

their owners, but on very large plantations, where slave owners

often employed overseers, slaves might rarely see their masters.

Some owners left their holdings entirely in the care

of subordinates, usually hired white overseers but sometimes

slaves. A few slave owners were even black themselves: a small

percentage of free blacks owned slaves, in some cases as a ruse

so that they could protect family members, but more often to

profit from slave labor. Most slaves on large holdings worked

in gangs, under the supervision of overseers and slave drivers.

Some, however, especially in the coastal region of

South Carolina and Georgia, labored under the task system: they

were assigned a certain amount of work to complete in a day,

received less supervision, and were free to use their time as

they wished once they had completed their daily assignments.

In addition to performing field work, slaves served as house

servants, nurses, midwives, carpenters, blacksmiths, drivers,

preachers, gardeners, and handymen. |

~ Trends ~

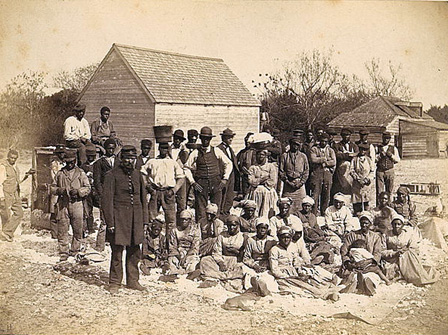

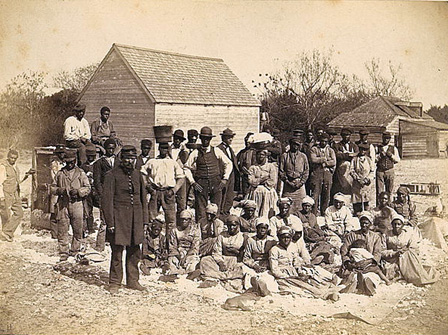

Slaves of the Confederate Genl.

Thomas F. Drayton, Hilton Head, S.C.

Despite such variations, there were a number of dominant

trends:

- First, slavery was overwhelmingly rural: in 1860 only about

5 percent of all slaves lived in towns of 2500 people or more.

- Second, although some slaves lived on giant estates and others

on small farms, the norm was in between: in 1860 about one-half

of all slaves lived on holdings of 10 to 49 slaves. The remaining

half of the slave population was evenly divided between larger

and smaller establishments. Holdings tended to be bigger in the

deep South than in the upper South.

- Third, most slaves lived with resident masters; owner absenteeism

was most prevalent in the South Carolina and Georgia low country,

but in the South as a whole it was less common than in the Caribbean.

- Fourth, most able-bodied adult slaves engaged in field work.

Owners relied heavily on children, the elderly, and the infirm

for "nonproductive" work such as house service; only

the largest plantations could spare healthy adults for exclusive

assignment to specialized occupations.

The main business of Southern farms and plantations,

and of the slaves who supported them, was to grow cotton, tobacco,

rice, corn, wheat, hemp, and sugar. |

~ Slave Treatment ~

|

Southern slave holders took an active role in

managing their property. Viewing themselves as the slaves' guardians,

they stressed the degree to which they cared for them. The character

of such care varied, but in purely material terms such as food,

clothing, housing, and medical attention, it was generally better

in the pre-Civil War period than in the colonial period. Judging

by measurable criteria such as slave height and life expectancy,

material conditions also were better in the South than in the

Caribbean or Brazil.

Although young children were often malnourished, most

working slaves received a steady supply of pork and corn, which

if lacking in nutritional balance (about which Americans of the

era knew nothing) provided sufficient calories to fuel their

labor. Slaves often supplemented their rations with produce that

they raised on garden plots allotted to them. Clothing and housing

were crude but functional: slaves typically received four coarse

suits (pants and shirts for men, dresses for women, long shirts

for children) and lived in small wooden cabins, one to a family.

Wealthy slave owners often sent for physicians to

treat slaves who became ill; given the state of medical knowledge,

however, such treatment-which could range from providing various

concoctions to "bleeding" a patient-often did as much

harm as good. |

|

Masters intervened continually in the lives

of their slaves, from directing their labor to approving or disapproving

marriages. Some masters made elaborate written rules, and most

engaged in constant meddling, directing, nagging, threatening,

and punishing. Many took advantage of their position to exploit

slave women sexually.

What slaves hated most about slavery was not the hard

work to which they were subjected, but their lack of control

over their lives, their lack of freedom. Masters may have prided

themselves on the care they provided, but the slaves had a different

idea of that care. They resented the constant interference in

their lives and tried to achieve whatever autonomy they could.

In the slave quarters, the collection of slave cabins that on

large plantations resembled a miniature village, slaves developed

their own way of life and struggled to increase their independence

while their masters strove to limit it. The character and resolution

of this struggle depended on a host of factors, from size of

holdings and organization of production to residence and disposition

of masters. Masters rarely were able, however, to shape the lives

of their slaves as fully as they wanted. |

~ Slave Life ~

The Hermitage, slave quarters,

Savannah, Ga.

|

Away from the view of owners and overseers, slaves

lived their own lives. They made friends, fell in love, played

and prayed, sang, told stories, and engaged in the necessary

chores of day-to-day living, from cleaning house, cooking, and

sewing to working on garden plots. Especially important as anchors

of the slaves' lives were their families and their religion.

Throughout the South, the family defined the actual

living arrangements of slaves: most slaves lived together in

nuclear families with a mother, father, and children. The security

and stability of these families faced severe challenges: no state

law recognized marriage among slaves, masters rather than parents

had legal authority over slave children, and the possibility

of forced separation, through sale, hung over every family. These

separations were especially frequent in the slave-exporting states

of the upper South. Still, despite their tenuous status, families

served as the slaves' most basic refuge, the center of private

lives that owners could never fully control.

Religion served as a second refuge. In the colonial

period, African slaves usually clung to their native religions,

and many slave owners were suspicious of others who sought to

convert their slaves to Christianity, in part because they feared

that converted slaves would have to be freed. During the decades

following the American Revolution, however, Christianity was

increasingly central to the slaves' cultural life. Many slaves

were converted during the religious revivals that swept the South

in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

Slaves typically belonged to the same denominations

as white Southerners, the largest of which were the Baptists

and Methodists. Some masters encouraged their slaves to come

to the white church, where they usually sat in a special slave

gallery and received advice about being obedient to their masters.

In the quarters, however, there developed a parallel, so-called

"invisible" church controlled by the slaves themselves,

who listened to sermons delivered by their own preachers. Not

all slaves had access to these preachers and not all accepted

their message, but for many religion served as a great comfort

in a hostile world. |

~ Slave Resistance ~

|

If their families and religion helped slaves to avoid

total control by their owners, slaves also challenged that control

more directly through active resistance. Their ability to resist

was limited. Unlike slaves in Saint-Domingue, who rebelled against

their French masters and established the black republic of Haiti

in 1804, slaves in the United States faced a balance of power

that discouraged armed resistance.

When it did occur, such resistance was always quickly

suppressed and followed by harsh punishment designed to discourage

future rebellion. In some instances, planned slave rebellions

were nipped in the bud before an actual outbreak of violence.

Such aborted conspiracies occurred in New York in 1741, in Virginia

in 1800, and South Carolina in 1822.

The most notable uprisings included the Stono Rebellion

near Charleston, South Carolina in 1739, an attempted attack

on New Orleans in 1811, and the Nat Turner insurrection that

rocked Southampton County, Virginia, in 1831. The Turner insurrection,

which at its peak included 60 to 80 rebels, resulted in the deaths

of about 60 whites; the number of blacks killed during the uprising

and executed or lynched afterward may have reached 100. But the

rebellion lasted less than two days and was easily suppressed

by local residents. Like other slave uprisings in the United

States, it caused enormous fear among the whites, but it did

not seriously threaten the institution of slavery. |

|

Less organized resistance was both more widespread

and more successful. This included silent sabotage, or foot-dragging,

by slaves, who pretended to be sick, feigned difficulty understanding

instructions, and "accidentally" misused tools and

animals. It also included small-scale resistance by individuals

who fought back physically, at times successfully, against what

they regarded as unjust treatment.

The most common form of resistance, however, was flight.

About 1000 slaves per year escaped to the North during the pre-Civil

War decades, most from the upper South. This represented only

a small percentage of those who attempted to escape, however,

since for every slave who made it to freedom, several more tried.

Other fugitives remained within the South, heading for cities

or swamps, or hiding out near their plantations for days or weeks

before either returning voluntarily or being tracked down and

captured. |

~ Tensions Between Free North

& Slave South ~

|

Slavery was an increasingly Southern institution.

Abolition of slavery in the North, begun in the revolutionary

era and largely complete by the 1830s, divided the United States

into the slave South and the free North. As this happened, slavery

came to define the essence of the South: to defend slavery was

to be pro-Southern, whereas opposition to slavery was considered

anti-Southern. Although most Southern whites did not own slaves

(the proportion of white families that owned slaves declined

from 35 percent to 26 percent between 1830 and 1860), slavery

more and more set the South off from the rest of the country

and the Western world. If at one time slavery had been common

in much of the Americas, by the middle of the 19th century it

remained only in Brazil, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the southern

United States. In an era that celebrated liberty and equality,

the slaveholding Southern states appeared backward and repressive.

In fact, the slave economy grew rapidly, enriched

by the spectacular increase in cotton cultivation to meet the

growing demand of Northern and European textile manufacturers.

Southern economic growth, however, was based largely on cultivating

more land. The South did not undergo the industrial revolution

that was beginning to transform the North; the South remained

almost entirely rural. In 1860 there were only five Southern

cities with more than 50,000 inhabitants (only one of which,

New Orleans, was in the Deep South); less than 10 percent of

Southerners lived in towns of at least 2500 people, compared

to more than 25 percent of Northerners. The South also increasingly

lagged in other indications of modernization, from railroad construction

to literacy and public education. |

The Cedars, Slave Cabin, Barnhart,

Jefferson County, MO

|

The biggest gap between North and South, however,

was ideological. In the North, slavery was abolished and a small

but articulate group of abolitionists developed. In the South,

white spokesmen, from politicians to ministers, newspaper editors,

and authors, rallied around slavery as the bedrock of Southern

society. Defenders of slavery developed a wide range of arguments

to defend their cause, from those based on race to those that

stressed economic necessity. They made heavy use of religious

themes, portraying slavery as part of God's plan for civilizing

a primitive, heathen people. |

|

Increasingly, however, Southern spokesmen based their

case for slavery on social arguments. They contrasted the harmonious,

orderly, religious, and conservative society that supposedly

existed in the South with the tumultuous, heretical, and mercenary

ways of a North torn apart by radical reform, individualism,

class conflict, and, worst of all, abolitionism. This defense

represented the mirror image of the so-called free-labor argument

increasingly prevalent in the North: to the assertion that slavery

kept the South backward, poor, inefficient, and degraded, proslavery

advocates responded that only slavery could save the South from

the evils of modernity run wild.

From the mid-1840s, the struggle over slavery became

central to American politics. Northerners who were committed

to free soil, the idea that new, western territories should be

reserved exclusively for free white settlers, clashed repeatedly

with Southerners who insisted that any limitation on slavery's

expansion was unconstitutional meddling with the Southern order

and a grave affront to Southern honor.

In 1860 the election of Abraham

Lincoln as president on a free-soil platform set off a major

political and constitutional crisis, as seven states in the Deep

South seceded from the United States and formed the Confederate

States of America. The start of the Civil War between the

United States and the Confederacy in April 1861 led to the additional

secession of four states in the upper South. Four other slave

states-Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri-remained in

the Union, as did the new state of West Virginia, which split

off from Virginia. |

~ The End of Slavery In America

~

|

Freed slaves under Union Army guard leaving

their plantations. |

|

Harper's Weekly February

21, 1863 |

|

Ironically, although Southern politicians supported

secession in order to preserve slavery, their action led instead

to the end of slavery. As the war dragged on, Northern war aims

gradually

shifted from preserving the Union to abolishing slavery and

remaking the Union.

This goal, which received symbolic recognition with

the Emancipation Proclamation that President Lincoln issued on

January 1, 1863, became reality with the 13th Amendment to the

Constitution, passed by Congress in January and ratified by the

states in December 1865.

Although slavery was ended, it was followed by an

intense struggle during Reconstruction over the status of the

newly freed slaves. In subsequent decades, black Americans continued

to struggle against poverty, racism, and segregation, as they

sought to overcome the bitter legacy of slavery. |

(See Bibliography below)

| Back to Timeline

| or click on your browser's "back to previous page"

button

©

Photographs: Library of Congress

Bibliography: Anstey, Roger, and Antippas, A. P., The Atlantic

Slave Trade and British Abolition, 1760-1910 (1975); Ball,

Charles. Fifty Years in Chains; or, The Life of an American

Slave. Ed. Isaac Fisher. New York: H. Dayton, (1859); Barker,

Anthony J., The African Link: British Attitudes to the Negro

in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade, 1550-1807 (1978);

Barrow, Reginald K., Slavery in the Roman Empire (1928);

Beachey, R. W., The Slave Trade of Eastern Africa (1976);

Bloch, Marc, Slavery and Serfdom in the Middle Ages, trans.

by W. R. Beer (1971); Coupland, Reginald, The British Anti-Slavery

Movement, 2d ed. (1964); Cratin, Michael, Roots and Branches:

Current Directions in Slave Studies (1980); Curtin, Philip

D., The Atlantic Slave Trade: A Census (1969); Davis, David

B., The Problem of Slavery in the Age of Revolution, 1770-1823

(1975), Slavery and Human Progress (1984), and The Problem

of Slavery in Western Culture (1988); Detweiler, Robert, and

Kornweibel, Theodore, Slave and Citizen: A Critical Annotated

Bibliography on Slavery and Race Relations in the Americas

(1983); Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick

Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself. Boston: American

Anti-slavery Society, (1845); Du Bois, W. E. B., The Suppression

of the African Slave-Trade to the United States of America, 1638-1870

(1896; repr. 1973); Fedric, Francis. Slave Life in Virginia

and Kentucky; or, Fifty Years of Slavery in the Southern States

of America. Ed. Rev. Charles Lee. London: Wertheim, Macintosh,

and Hunt, (1863); Filler, Louis, Crusade against Slavery: Friends,

Foes, and Reforms 1820-1860, ed. by Keith Irvine, 2d rev.

ed. (1986); Finley, Moses I., ed., Slavery in Classical Antiquity

(1968); Fogel, Robert W., and Engerman, Stanley, Time on the

Cross, 2 vols., (1974; vol. 1, repr. 1985); Genovese, Eugene

D., The Political Economy of Slavery (1965) and Roll, Jordan,

Roll (1974); Hellie, Richard, Slavery in Russia (1982);

Irwin, Graham, Africans Abroad: A Documentary History of the

Black Diaspora in Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean (1977);

Jackson, John Andrew. The Experience of a Slave in South Carolina.

London: Passmore and Alabaster, (1862); Klein, Herbert S., African

Slavery in Latin America and the Caribbean (1986); Lewis,

Bernard, Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical

Enquiry (1990); Litwack, Leon F., Been in the Storm So

Long: The Aftermath of Slavery (1979); Lovejoy, Paul E., ed.,

Africans in Bondage: Studies in Slavery and the Slave Trade

(1987); Mellafe, Rolando, Negro Slavery in Latin America,

trans. by J. W. S. Judge (1975); Meltzer, Milton, Slavery:

From the Rise of Western Civilization to the Renaissance (1971)

and Slavery II: From the Renaissance to Today (1972); Miller,

Joseph C., ed., Slavery: A Worldwide Bibliography, 1900-1982

(1985); Parish, Peter J., Slavery, History and Historians

(1989); Patnaik, Utes, and Dingwaney, Manjari, eds., Chains

of Servitude: Bondage and Slavery in India (1985); Patterson,

Orlando, Slavery and Social Death (1982); Pinney, Roy,

Slavery, Past and Present (1972); Pope-Hennessy, James,

Sins of the Fathers: A Study of the Atlantic Slave Traders,

1441-1807 (1967); Reilly, Linda C., Slaves in Ancient Greece

(1978); Sawyer, Roger, Slavery in the Twentieth Century

(1986); Stampp, Kenneth M., The Peculiar Institution: Slavery

in the Ante-Bellum South (1956; repr. 1964); Watson, Alan,

Roman Slave Law (1987); Watson, James L., Asian and African

Systems of Slavery (1980); Wiedemann, Thomas, Greek and

Roman Slavery (1981); Wilbur, Clarence M., Slavery in China

during the Former Han Dynasty, 206 B.C.-A.D. 25 (1943; repr.

1967); Winks, Robin W., Slavery: A Comparative Perspective

(1972); Yavetz, Zvi, Slaves and Slavery in Ancient Rome (1988).

© Copyright "The American Civil War" - Ronald

W. McGranahan - 2004. All Rights Reserved.

![]()