|

|

Evgenii Monyushko, 1944 |

The battery to which the messenger had led me was deployed in an indirect firing position near a small farm. The 76mm ZIS-3 guns were dug in, but they were not sufficiently camouflaged from an IPTAP (anti-tank artillery regiment) soldier's point of view. On the other hand, indirect fire was not the same as fire over open sights. My first PNP (forward observation post) which, like all the subsequent ones, had the call sign of "Dolina-1" ("Valley-1") was located on the northern side of a gently sloping hill 188.1, about 100 meters from the top. A dug-out shelter had been constructed there, cutting into the side of an irrigation ditch, which had a depth of around two meters. Water flowed at the bottom, so you could move only along a narrow path beaten right near the water's edge. Movement was allowed only in the darkness because the ditch was perpendicular to the front line and could be observed by the enemy. Shallow trenches of our infantry ran next to our dug-out and passed to the left, to the top of the hill 188.1 occupied by us, and to the right, to the edge of the town of Dankwitz, still occupied by the Fritzes. The hill was not in the sector of the rifle detachment to which the battery was attached. Apparently, the PNP was not deployed on the slopes of the hill for that reason, although if we were located there, with a good field of view, we could perform our tasks better in the interest of "our" infantry. The presence of my PNP in the infantry combat formations was basically a formality. I couldn't direct the battery's fire myself because I didn't have a map and didn't know the coordinates of the firing positions. But, of course, thanks to the presence of communications, I could always report the situation to the battery commander, call for fire, even communicate with the entire artillery battalion. I could also correct the fire, but only through the battery commander, transmitting the deviation of explosions from the target in meters and directions. The battery commander was supposed to convert them to the required settings for the guns. The main thing was that the artillery men were next to infantry, as required by the field manual.

Our dug-out was small, approximately 2x2 meters, its height -- about 1 meter -- allowed us only to lie, which is easily explained: we couldn't build a tall roof taking the requirements of camouflage into account, and we didn't have any materials for that either. But the water running through the ditch did not allow us to dig deeper. The roof was only boards, straw, and a thin layer of dirt. There was no layer of logs on top. A ground sheet substituted for the door, it was rolled up during daylight for illumination. During the nights we had "telephone illumination" -- a piece of PTF-7 telephone cable, which had cotton insulation soaked in resin that would burn with a dim smoky flame, was hung from stakes driven into the walls of the dug-out along its entire perimeter. In the evening the cable would be lit from one end, in several hours it would burn through to the other. Faces, hands, clothes would be black with soot in the morning. On rare occasion we would get trophy candles -- lampions. We conducted our observation through the "Scout" type periscope, which was stuck right through the boards of the roof. No movement could be seen inside the German positions, same as ours, during daylight. Two burned out tanks stood between our trenches and the edge of Dankwitz. They had been destroyed before our arrival to the PNP. The infantrymen said they had both been destroyed by mines.

|

The 2nd Battery 9th Art. Regiment forward NP near the town of Dankvic, on the northern slope of Hill 188.1. February 1945. Author's drawing, February 1945. |

Food was brought to us twice daily: before dawn and after the dark settled. Remembering the German surprise with the cold bath, we constantly monitored the water level in the ditch. A corpse laid in the water near the entrance to the dug-out. A small purling current of water flowed through its back sticking out of the water and left a line of bubbles on the greatcoat. When the water level fell, his line could be seen for some time above the water level. If it rose, there was no distance between the bubbles and water. This alarmed us: 10-15 centimeters more, and we would have to bail out of the dug-out, very probably right under the enemy fire...

Apparently, the hill 188.1 was of interest to the Germans -- our rear could be seen from it to the distance of at least 2-3 kilometers. Once, during the day, the Germans suddenly broke through to the hill. It wasn't difficult with the extremely sparse infantry combat formations. The battalion commander immediately organized a counterattack and beat the Germans back.

This event alarmed the command, and that same day, when the dark settled, the battery commander Metelsky appeared at the PNP with the rest of my platoon. Several holes had been dug into the sides of the ditch next to our dug-out. A small number of replacements arrived to the infantry. During the night the Germans fired on us from a small caliber AA machine gun, installed on an APC. The sound of its engine could be heard very well, and long bursts of tracer shells flew from there to the slopes of the hill. The crackle of their explosions, the sounds of firing merged into one, so it seemed that we were fired upon form somewhere very near. Although, that probably was the case.

Our battery on the orders of Metelsky (the battery commander) started firing almost blindly since we didn't know the exact location of the target, and besides, the Germans fired while constantly changing their position. Still, after several salvos from the battery, the German fire ceased.

|

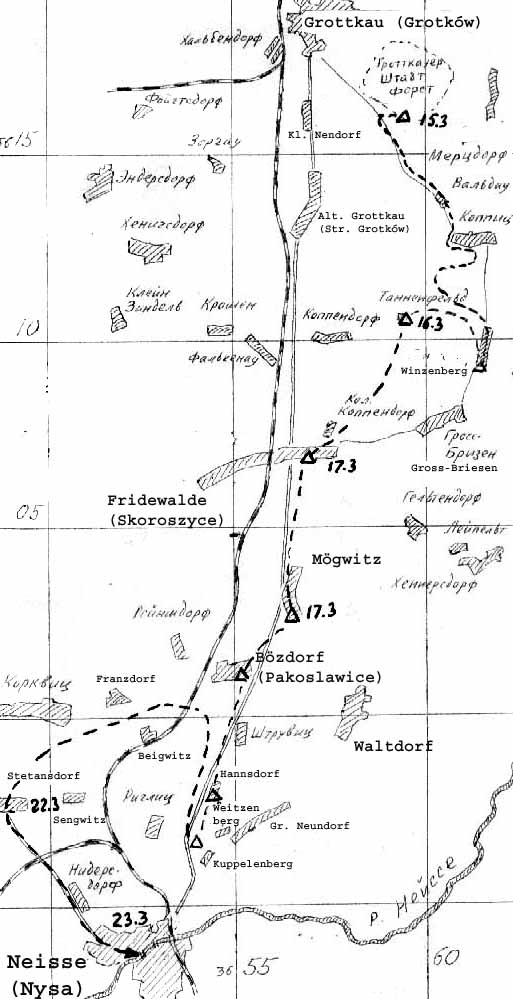

The general diagram of the combat area for the 9th Artillery Regiment

in February-May 1945. Scale 1:500,000 City names are given as of 1945 when possible. In case the name changed, the modern name is given in parantheses in the original transcription. |

The next morning started with a new German attempt to capture the hill 188.1. This time -- after a rather sound artillery bombardment. Although, only the artillery pieces of caliber not higher than 105mm participated, but for no less than 15 minute the fire was so dense, that you almost couldn't tell the different explosions apart in the unbroken roar and wail of shells and fragments. Then the shelling was repeated more than once. The telephone communications were interrupted from the very beginning of the bombardment. Radio operators Ivanov and Burenkov, who had arrived with Metelsky the day before, immediately deployed their A7-A radio set and contacted the battery. As soon as the bombardment subsided a little, a telephone operator Sukhanov was sent on my order to check the line. Time passed, communications were not getting restored, although it was clear that the break was close to the NP (observation post) -- the Germans did not fire at our rear. Then Vania Skorogonov crawled to the line, quickly restored the connection and dragged Sukhanov back with him -- he was lying there alive and well. By that time Metelsky was already giving orders to Shutrik by radio. Nevertheless, as soon as the firing platoons' call sign "Bukhta" ("Bay") could be heard through the crackle and rustle of cables being connected, the battery commander abandoned radio and came over to the telephone operators. Either he, like many during that time, mistrusted radio communications or had an exaggerated impression of the capabilities of radio homing.

In order to finish the story about the hill 188.1, it must be noted that if the day before the Germans managed to capture it even for a short time, this time all their efforts, thanks to the timely efforts of our command, did not bring them even a short-lived success. But all artillery men not involved into directing the battery's fire participated in combat together with infantry to repulse the attack.

Several things about our communications have already been mentioned. I'll discuss this question in more detail.

There were radios of two types in the platoon: A7-A and RBM. The first had a short range: about 10-15 kilometers depending on the receive mode and the condition of its batteries. It worked using the principle of frequency modulation, thanks to which it was less affected by interference. We used the A7-A with a microphone, and in general radio operators preferred the microphone channel, since the majority of them didn't feel themselves too comfortable with the Morse code transmission.

|

Telephone operator in the dug-out shelter. Author's drawing, February 1945. |

I want to emphasize again that the majority of officers considered telephone as the main type of communications. And it was so in reality. A cable phone wire was laid to an NP, PNP at the first opportunity, and if the disposition remained constant for a while, a "permanent" line was also laid. This word was used to call any phone line laid not with the regular telephone cable, but from improvised materials: pieces of various electric lines, many of which remained along roads, different pieces of wire, sometimes even barbed wire. Since such wiring usually didn't have insulation, it was installed on various supports, posts, drawn through the air between trees and ruins of buildings while also trying to establish parallel sectors for reliability and stability of communications. The name came from the similarity of some sectors of such line to permanent lines of "civilian" communications, installed on poles. First, the "permanent" line allowed us to roll up the regular cable before hand, and not spend any time doing that when changing our disposition. Obviously, in the proximity of NP, in areas observed by the enemy, the cable lines were not replaced by "permanent" ones. Second, the use of "permanent" lines allowed us to create better branching communications network. After all, the supplies of the regular cable in the battery were not large -- a total of 10-12 km.

But let's get back to reconnaissance. I can't even remember how many forward NP's Senior Sergeant Kolechko and I changed in a short period of time. As a rule, we were deployed among rifle companies, in the forward positions. It is interesting to compare the various definitions of "forward positions" that exist at different levels. If somewhere they considered the area where the command posts of regiments or even divisions of the first echelon were deployed as the forward positions, the infantry justly considered even the indirect firing positions of divisional artillery as deep in the rear. But I can say without boasting that our "Dolina-1" was in the forward positions from any point of view. I've already mentioned this, but I want to emphasize our limited capabilities at the forward NP again. All actions -- only through the battery commander. There was no map, the location of the firing positions wasn't always known. But still our appearance in the infantry trenches uplifted the spirits of company and platoon commanders, and even privates: after all, the artillery was nearby and would help out if anything happened.

Of course, besides direct involvement in the course of actions, our main task was reconnaissance and the transfer of information about everything to the battery commander and the battalion's chief of intelligence.

The time of the operation that came to be known as Upper Silesian in the history of the Great Patriotic War was coming closer and closer. (The reason the operation received that name is not understood. Maybe, to differentiate it from the just completed Lower Silesian Operation. The operation that began on March 15 was conducted on the territory of Oppelnskaya Silesia (in Polish, Opolskiy Shlionsk), and is called Opolskaya Operation in the Polish military-historical literature. The Upper Silesia itself had been liberated as far back as January 1945.)

The 2nd Battery 9th Artillery Regiment NP (PNP) movement diagram during the Upper Silesian Operation 15-23 March 45. Scale 1:10000

City names are given as of 1945 when possible. In case the name changed, the modern name is given in parantheses in the original transcription.

Finally, in the night of March 15, somewhere to the right of us where the Grottkau-Neisse highway was, we could hear the rumble of tank engines and tracks, which could be recognized by scouts even in the dark as coming from T-34's. Tanks appeared, it would begin soon! March 15 arrived. The time to commence artillery bombardment came. During the very first salvos, the glow from gunshots and explosions completely blinded the eyes. Darkness and light replaced each other with enormous frequency. The roar was such that you couldn't hear not only speech, but also yelling. It became impossible to observe target destruction from the NP: the explosions blended into an unbroken line of fire, smoke, uplifted soil, various wreckage. Everything flew, flashed... The explosions were storming 300-400 meters from the NP. All unnecessary personnel had been pulled back about a hundred meters to the rear, toward the dug-outs, just in case. But no one wanted to hide -- they believed in the mastery of our artillery men, our equipment. Everybody wanted to see what was going on with their own eyes. Of course, you also had to beware German fire in response, but we didn't get that in our sector.

After the powerful initial bombardment which continued for what seemed like 10 minutes, the infantry reconnaissance detachments moved forward and found out that the Germans had left the first line of defense, leaving only covering forces.

We started to march forward behind the infantry and together with it. At first we tried to lay the telephone line, but then switched to radio, and laid the wire only during compulsory stops. The day of March 15 was sunny, warm, although the morning started gloomy. I remember how hard it was to run up some slope, and there was only one thought -- reach the crest faster, where the first soldiers were already lying, and lie down with them to rest a little. But those on top laid down not because of exhaustion, but because the Fritz was snapping back at us with fire from beyond the crest. We pulled up, established communications with the fire platoons. The battery commanders called for artillery fire... And again forward, further.

Another picture stands before my eyes. A highway passes through a wide hollow from an area already captured by us to the south, toward the Germans. It's hard to move through a soaked spring field for both infantry and vehicles -- everyone assembles on that road. Our group, the battery commander, me, and the bigger part of the HQ platoon (some signalers are at the lines and the firing positions), gradually drifts in the same direction together with the infantry we are attached to. In the hollow, at the lowest point in the road, there is a small ruined bridge over a stream. Next to the bridge a crossing was constructed out of its wreckage. Infantry runs over it, slipping in the mud, and a tank that left the highway inches forward through it. The logs wriggle under the T-34's tracks, one of them presses a mine lying on the ground with its end. The explosion was about 30 meters from us. Wounded, killed infantrymen fall. The tank moves on...

Running, we crossed the stream after the tank. Ahead of us, about 500-700 meters, there was a small town to the left of the road. That was Waldau. A small belltower could be seen over the houses. From there, from the direction of Waldau, several infantrymen had been downed by single shots. Everybody fell to the ground, opened rabid fire with their rifles, machine guns, although it's doubtful that anyone had time to see the sniper, there wasn't enough time for that, and it wasn't that close either. Nevertheless, no one shot at us after that, I don't think we killed the sniper, just scared him away, and the presence of the tank also contributed.

We passed Waldau. Metelsky was cautious and although he kept our group close to the infantry, but not in the common crowd, we were walking several dozens meters to the side of the road, on the left. A narrow strip of an apple orchard crossed our path approximately three kilometers beyond Valdau. The trees were still naked, of course, growing in straight rows. To the front and to the back, from the north and the south, the orchard was bracketed by deep ditches, filled with water. These ditches saved us: when we were already crossing the orchard, a salvo from "Katiushas" descended on it. We fell into the ice cold water, hid in the ditch. Fortunately, none of us were hit.

The second day of the offensive is on. Our tankers are suffering heavy losses. Burned out vehicles, with turrets torn off by explosions, remain in memory, charred bodies thrown out during an explosion, or maybe they had managed to bail out before being mowed down by a German machine gunner. When the fighting was over, in the relatively "quiet" period, I made pencil sketches. Fortunately, some of them still remain.

Winzenberg has just been cleared from Germans. Sparsely built houses, fenced gardens between them, sheds. Beyond a field stretching about one and a half kilometers -- a line of trees, pointed tile roofs can be seen between them. That's Gross-Briezen. Germans are there. Tankers' attempts to break through to it are unsuccessful. Apparently, there are tanks or SPG's entrenched there.

|

Fighting for Gross-Briezen, 15 March 1945. |

An RBM radio set is deployed near a shed's wall on the edge of "our" Winzenberg. The artillery battalion commander Shliahov reports to someone "on top": "...we're fighting for Gross-Brizen. The combat is heavy, boxes (tanks) are burning..."

My spotters deploy the equipment, begin to search for targets. Shliahov enters the shed with some of the battalion's officers: it looks to him it would be better to observe from there through the holes and cracks in the wall. At that moment a shell fired from the edge of Gross-Brizen pierces both brick walls of the shed and with a squealing sound flies on toward our rear. Shliahov and the officer that followed him jump out of the shed, swearing furiously. Both are bruised, their tunics red with brick dust. Fortunately, the shell turned out to be a dud.

An artillery bombardment of Gross-Briezen by all three batteries of the battalion follows in response...

We bypassed Gross-Briezen from the north together with the infantry and armor, and came to the Grottkau-Neisse highway. Fridewalde stretched in a long stripe across the highway going south. We passed through the western part of that town, and captured Mögwitz by the end of the third day of fighting, on March 17.

Unlike Friedewalde, that village stretched in a stripe not across the highway, but along, mostly to the left of it. In two-three houses on the southern end of Mögwitz, facing toward the enemy, a large number of NP's had concentrated in the attics: the artillery was there, and infantry, even the tankers. A market, not an NP. Vasiliy Kolechko was being loudly indignant that the basic rules of camouflage were not followed, but neither he nor I could do anything -- I was only a junior lieutenant. But shoulder straps with even two stripes (major to colonel) were not a rarity there...

Two incidents occurred in the morning of March 18. Germans were still holding Bözdorf -- about a kilometer and a half to the south. Our infantry hadn't yet advanced further than Mögwitz's edge. And suddenly a truck driving on the highway from our rear appeared. 10-12 people were standing in the back, many of them officers, judging by their caps. The truck was driving fast, because of the surprise no one had time to stop it in Mögwitz, it drove past the last houses where our observation posts were located. We started shooting behind the truck... Finally they understood -- started braking, turning around. Germans also opened fire, but they were too late.

We were still discussing what had just occurred, no more than half an hour had passed, when a German passenger commander's car -- a "fritzwillys", as Kolechko put it -- appeared, driving fast toward us. We hesitated in surprise, then ran downstairs grabbing our weapons, but someone from the infantry had already fired a burst. The light all-terrain vehicle flew into a side ditch. We took the driver alive, but the officer riding in the car had been killed on the spot. We found out from the driver that he had been a headquarters representative riding to restore order among the retreating units. He thought that the fighting was on the approaches to Friedewalde, that is 3-5 kilometers to the north. That happens when situation reports are late or outpace the events.

By that time the infantry had reached the line of a small separate house to the left of the Grottkau-Neisse highway, a little to the south of a small Hannsdorf village. We deployed our PNP in that house. For some reason we decided that it was the house of the road supervisor.

The sparse line of barely entrenched infantry stretched to the left starting from the house's walls, and a little to the right, intersecting the highway. Everything inside could be literally swept with fire through the windows with frames knocked out, holes in the walls, and not only by infantry weapons -- the door that separated a room from the kitchen had a circular, as if cut with a compass, hole from an armor piercing shell.

We established communications, deployed the periscope for observation.

The rifle company commander crawled to us for a visit, said that he had no more than 30 soldiers in the sector of about half a kilometer.

After reporting the situation to the battery commander, the NP's location, we received an order to continue observing, wait for further instructions. We stayed for two days there. I remembered some moments.

Three tankers in black coveralls and ribbed tank helmets made their way from the rear side of the house during the day. They declared that they had come to take a look at the road. They didn't pay attention to our warnings about the danger, and even responded somehow rudely to our offer to use our periscope. One of them got up the staircase from the basement, right near the door pierced by the shell, stood up and immediately fell in our and his comrades' arms. The bullet pierced him right through his chest. The tankers crawled away dragging their comrade with them. He either lost consciousness or was dead.

In the evening of May 4 Metelsky ordered me to secure the transfer of the battery NP from Marksdorf to the northern approaches to Tsobten, still occupied by the enemy. There wasn't much time left before dark, but we couldn't afford to wait until the darkness settled for a safe way out of Marksdorf -- we needed time to find an NP with a good view while there was still visibility. We grabbed our weapons and a surveying compass and, together with Kolechko, sometimes crawling, sometimes running, crossed the dangerous sector and set out toward the southern end of Rogau-Rozenau. On the way, despite the deficit of time, we spent a quarter of an hour to look at the visual demonstration of the new 100mm gun's merits -- a "sotka", as it was called. By the way, this was the first and only time I ever saw it in action. The "sotka" turned up here while passing through, as they say. A lone tracked tractor was pulling the single gun to somewhere along the front line. Infantry that was in their positions somewhere on the edge of a farm, had stopped the tractor, and the soldiers tried to talk the senior lieutenant into "scaring" a German tank which they had seen in a village at the distance of a kilometer and a half. The "senior" tried to wave them off, but then he got interested, looked. Kolechko and I also got interested and decided to see how it would end. The gun crew detached the gun on the senior lieutenant's order and rolled it to a convenient spot, assisted by the infantrymen. While they were preparing the gun for action, the tractor turned and backed toward the gun. They took a single shell out of the box, carefully aimed the gun, having determined the distance to set the sight by the map. A single shot -- the tracer shell pierced the armor and the tank burst into flames. And the "gunners", not wasting any time, were already attaching the gun to the tractor. I wished that we had such a gun in 1944 in our IPTAP (anti-tank artillery regiment) at the Sandomierz bridgehead.

Despite the unforeseen delay, we managed to find a spot when it was still light, or rather before complete darkness settled. There were earth walls raised between Rogau and Tsobten, apparently for protection against floods. We decided to cut the trench for the post into such a wall.

Evgenii Monyushko (on the left) and Vasilyi Kolechko. Czechoslovakia, 1945 |

The attack began after a very short -- about 10 minutes -- artillery bombardment. There were few tanks, there were only 2 or 3 vehicles in a rather wide sector that could be seen from the NP, but then they were the heavy IS-2's. They drove slowly, carefully, not outpacing the infantry, supporting it by the fire over their heads. Nevertheless, the infantry started to advance energetically, and Kolechko and I, as always, also had to move forward, so that we wouldn't lose "our" company in the city. A telephone operator started to lay his wire after us. We crossed almost the entire small town with the infantry. When we got to the south end we were stopped by heavy fire from the Germans entrenched in the last houses in the south. While we tried to throw them out of there, Germans bypassed the town from both flanks and entered it from both east and west, almost connecting in the center, and cut us off. At the same time those still in the city counterattacked.

Before my eyes a heavy machine gun crew, trying to take the position about 20-30 meters from our NP in the center of the town square, was destroyed by a direct hit of a shell fired along the street from the south end of the town.

I didn't have a direct link to the firing positions, the telephone line connected us only to the battery commander who, with the main part of the HQ platoon was in the northern end of Tsobten. Using the map that the battery commander had given me for that day, I was pointing out the sectors that needed to be fired upon, and Metelsky was preparing the data and passing the orders to the firing positions.

When it was found that the Germans that had oozed from the flanks appeared in the town's center between us and the battery commander, I requested fire on that area, which caused Metelsky's indignation, he even said that I couldn't read a map. With difficulty I convinced him that the problem was not in a topographical error, but in the changed situation, about which they didn't even suspect there in the main NP. After that the battery fired several salvos. Soon after the start of firing the connection was broken: either we broke the line ourselves, or the Germans, having found our telephone cable passing through an area already taken by them, cut it. After the communications were broken we had to join the infantry, since there could be no question of fixing the line. We retreated together with the infantry, sometimes crawling, sometimes running, making our way through holes in building walls and fences. I can't forget that if it wasn't for Kolechko, I could've been unable to get out of Tsobten alive. Having run through a small garden enclosed by two meter high walls, we ran into Germans who, apparently not noticing us, were combing the garden with bursts from their SMG's. They were firing explosive bullets, which were bursting in the dense brush, which made it seem as if there was shooting from all sides among the branches. We fell to the ground and started crawling in different directions along the fence, in order to find an exit faster. A dead end turned out to be on my side. I laid down, prepared my SMG, although I didn't have much hope for it. The thing was that the day before that foray into Tsobten SMG's were taken away from many artillery men, including me, to better arm the infantry -- after all, I wasn't supposed to have a sub-machine gun according to the TO&E. Of course, right after we entered Tsobten, I found an SMG which apparently remained from a wounded or killed soldier, but the PPSh turned out to be broken -- it only fired single shots. Because of this I was feeling unarmed and uncertain. Then I felt somebody pulling at my leg -- Vasiliy came back for me after finding a breach in the wall and reconnoitering our way further. After joining the infantry, I armed myself with a carbine instead of the broken PPSh. We fought our way through to the northern end, where we found two battery commanders -- Gavrilenko and Metelsky -- and all the signalers from both batteries prepared to retreat. It turned out that an order had been received to get out of the town to the initial positions and march to a different sector from there.

On the southern edge of the Forst Nonnen Busch forest, about 3 km from Freiburg we became witnesses, and to some degree participants of the last serious combat engagement. Everything that happened after, including in Czechoslovakia after May 9, didn't have such tension. When the advancing infantry, and us artillery men with it, reached the line of the forest's edge, a line of German assault guns started to advance toward us ascending a gentle slope from the edge of Freiburg -- no less than ten on a front of about a kilometer. Urgent communications with the fire platoons. To Malyshev's howitzer battery -- open fire, and the "gunners" -- immediately deploy for direct fire. But it was clear that the Germans would arrive first -- they were already on the move, about two kilometers remained, and our guns were farther, and they also had to take off their positions and deploy on the new spot on top of that... It seemed that it would get hot. And then SU-152's, one of which by accident had almost finished us before that, appeared from behind our backs right through the forest and deployed into a similar line.

The slaughter began after several minutes. Six inch shell of our SPG's literally tore German boxes to pieces, but their return fire couldn't pierce the front armor of SU-152's. The desperate attempt to defend Freiburg ended in ten smoky fires through the entire field.

Comments by Evgenii Monyushko

Did you personally shoot at enemy soldiers?

There was only one time when no one except me was shooting, and I knocked out an enemy. It was either May 5 or 6 in Tsobton, Silesia. We were encircled and had to fight our way out of the town. We burst into a house, where a group of soldiers assembled, and started searching for where to run next. There was a fence on the opposite side of the street, about 100 meters away -- brick posts and bars between them. I looked out and saw either a German or a Vlasovite trying to climb over to our side. I had an SMG, but I couldn't be certain of a hit at such a distance. I pulled back and grabbed a carbine from a soldier, jumped out, aimed, and fired. I saw how he somersaulted backward, but we were leaving and I don't know what happened to him.

Was the divisional artillery used to suppress enemy artillery?

Artillery suppression was done by army and corps artillery regiments. They made use of sound ranging and aerial reconnaissance. Divisional artillery took almost no part in that except for suppression of mortar batteries. Divisional artillery's task was the suppression of 1-3 lines of trenches and to support our infantry. They would sometimes give a map case with photos from aerial reconnaissance before an offensive, and that was it.

Did you fire at specific targets, or by quadrants?

An artillery attack was never conducted simply by quadrants. We always fired

at selected targets. Of course, if a group of targets could not be seen from

an observation post, then areas where targets were located were suppressed.

Everything had to be suppressed to the distance of 15 kilometers from our initial

positions.

What decorations do you have?

An Order of the Patriotic War, 1st degree and Order of Red Star.

| Interview

Artem Drabkin Translated by Oleg Sheremet |

|

|

|

|