From Vision to Reality

During the reign of Alexander III it had been seen how the Industrial Revolution was transforming Western Europe and the North American continent into a tangible symbol of prestige, progress, and power. The basis for this progress was reliant on having a reliable and extensive railway network, and Alexander saw the benefits of such a mass transportation system. Towards the mid to late 19th century, Alexander was admiring the trans-continental railways of the USA and Canada together with the proposed plans for building of railways in Brazil and Africa. It was when he heard of a plan to connect Great Britain to India by rail that he decided that Russia must be part of this progress. The benefits to the military and the economics of Russia would be enormous, and would be of great political advantage. The policy of the Russian government, at the time, was for the Treasury to finance the construction of railways and then allow private operators to profit from their running. It was decided that it would be more advantageous to both the State and the populace to nationalise the railways. This was done under a policy entitled 'Vykup', which allowed the State to purchase all of the privately run railways in Russia and put them under State regulation. Up to 1880 only 25% of all the privately run railways were under State control, by 1900 this had risen to 60%. While all this was going on the people of Russia were very enthusiastic for the foresight of Alexander III and the availability to travel by railway across Russia.

While the private railways were being bought back by the State, Alexander and his son Nicholas (later to become Nicholas II) had a vision. This vision was to have a railway network that linked Western Russia to its extremities in the east. Nicholas was made the Chairman of the Committee of Siberian Railways in 1893, while Alexander carried on his duties as Emperor. In 1894 Nicholas, upon his father's death, became the new Tsar of Russia, but retained the position of Chairman of the Committee of Siberian Railways. His interest in constructing this railway network was a consuming passion, which had to be interrupted by affairs of State.

Tsar Nicholas II and Alexei in Guards uniforms.

It was evident, from the Russo-Turkish and Crimean wars, that the need for a system to transport troops around the country rapidly was desperately needed. Any invasion on the East Coast of Russia would prove to be impossible to contain until the East was connected to the West. The time to transport something from St. Petersburg to Vladivostok would normally be measured in months instead of days. This delay would be mainly because of the non-existent roads across the interior of Russia. What roads there were in the interior were nothing more than cart tracks, adequate for local travel but extremely arduous for travelling across the country. Hence the dire need for a system to convey a mass of troops and materiel rapidly from West to East, and the Trans-Siberian Railway was born.

Because Nicholas II had to govern Russia and attend to matters of State, it was decided to appoint Sergei Witte as Director of Ministry of Finance Department of Railway Affairs. His appointment was solely due to his enthusiasm and determination to see the Trans-Siberian Railway completed, which mirrored the vision of the Tsar. The dubious title of 'The Speranskii of railway legislation' was bestowed upon Sergei by one newspaper, and it quickly became widely accepted by the citizens of Russia. Speranskii was a Siberian (State Secretary 1810-1812 and State Governor 1819-1821) who got things done with the absolute minimum of meetings and talk. Together with his enthusiasm for the project Sergei Witte was the ideal person for the position. The railways were promoted as - belonging to the people and to no individual as well as serving all the social classes by giving the people access to the highest blessings of culture.

On the 15th of February 1891 the Tsar gave his blessing to the decision to build a railway across Siberia. This railway would link up with the present network already operating in the Western part of Russia, to allow uninterrupted travel from west to east. To put everything in context the Russians referred to the Trans-Siberian Railway as 'The Great Siberian Way', and this is how it was presented to the Russians. It was intended that the railway would be built in four sections, all starting at the same time. This was to maximise the effort required, and the complete network would be finished at the same time. The total distance of this railway would be 7,500 versts (5,000 miles) in length. The four sections would correspond to geographical divisions: Western Siberian; Central Siberian; Transbaikal; and Ussuri (in Eastern Russia). The estimated cost of this massive project was 350 million Roubles (approx. GBP14 million (US$23 million)), which translates to GBP750 million (US$1,232 Million) at today's prices. Such was the state of Russia's finances that outside backing was sought, so as not to strain the Treasury funds. Initially the Bankers, Rothchilds, were interested in funding the project to the sum of 300 million Roubles. Because this loan would mean that all the Baku oil exports using the railway would go directly to the Rothchilds, as a result this loan was refused. Other loans offered had similar monopolistic directives, and this meant that the Treasury financed the whole project without any outside assistance. This decision was not taken lightly, but any repairs and design flaws would have to be funded by the Treasury, thus causing a greater strain on its finances. It was this that showed it was more economical to fund the project as it progressed. On 19th May 1891 Tsarevitch Nicholas performed the earth-breaking ceremonies and laid the foundation stone of the passenger station at Vladivostok. A local Tomsk newspaper (Sibirskii Vestnik - Siberian Herald) wrote the following report about the ceremony:

'Siberia is for Russia, for the Russian people; the whole of Siberia consists in its close unity with the rest of Russia…. The wealth of Siberia is the wealth of Russia. Siberia is not a colony of Russia, but is Russia itself; not Russian America, but a Russian province, and should develop in the same way that the other borderlands of the 'Russian State' have developed.'

From Irkutsk (on the western side of Lake Baikal) the western route would go via major Siberian settlements to Omsk, Samara, Moscow, and St. Petersburg (which was the capital of Russia at the time). The primary concern was, as written in the Russkie Vedomosti (Russian Gazette) by A. I. Chprev, an economist and railway expert:

'The might and prosperity of the great powers of the world were based on industrial and commercial enterprises. This line would enable the minerals to be transported more quickly to the processing centres of Russia.'

In this vein the major export from Siberia to the world was furs, pelts, and hides for the fashion industry. The developed world was an eager buyer of all that came out of Siberia. The station at Moscow was the main terminus for all the goods brought from and destined for Siberia. Any items for export were then transported to St. Petersburg for shipping around the world.

During the 1880s major work on the transport systems were being undertaken in Russia. The Imperator Alexander II Bridge, which spanned the Volga River near Syzran, and the Ob' to Enisei canal that linked Irkutsk to Tiumen, were just two of the other projects. It was decided that these projects would enhance the progress and eventual trade connections with the Trans-Siberian Railway. The route that the railway would eventually take was decided to be Samara (terminus of the Western Russian Railway), to Ufa, Zlatoust, and Cheliabinsk to Omsk. From Omsk it would follow the old post road (more of a cart track in reality) through Krasnoiarsk, Kansk, Nizheudinsk to Irkutsk. The route east of Lake Baikal would go via Verkhneudinsk, Chita, Sretensk, Khabarovsk, and Vladivostok. While all this planning for the construction of the railway was being done, other planning was happening behind the scenes. This other planning was to get new settlers to colonise Siberia and to assist with the railway construction as it passed through their area. These settlers would populate the geographical areas that were best suited for commercial development.

Once the route was approved a proposal by Vyshnegradskii made a lot more common and economic sense. He proposed that 'the construction of this railway must proceed gradually… so that the local population, as well as the State, may derive some benefit from the matter.' The criterion centred around the income generated by each completed section. This would give some return on the investment while the project progressed, and it would be taken quickly to their place of work. This proposal was accepted and the four sections would now be built as the railway reached them, starting from Samara in the west and Vladivostok in the east. The lines would terminate at Lake Baikal and, therefore, progress would be achieved at twice the normal rate. The initial expense would be in transporting the equipment, by sea, to Vladivostok. Most of the committee time was spent attending to clashes of personalities and the commercial interests of its members.

To enable the railway to attract skilled technical employees to work on it, special plots along the right of way were formed. These special plots were large enough for a kitchen garden (¾ acre), whereas the plots available to the migrants were 40 acres. The migrants had their plots set out on arable land in groups of 100 plots. These groups of 100 plots were the basis for the formation of new villages (Otrub). Migrants from Western Russia tended to opt for isolated individual plots to set up home (Khutora). The exodus to Siberia was so great that the government had to drain swamps and irrigate the dry parts of the Steppes to accommodate all the migrants. A total of 18 million acres of land previously owned by the nomadic Kazakhs of Akmolinsk State was utilised. A further 42 million acres belonging to the Cossacks of the Ussuri region was to be used in the event of any overflow of migrants. To encourage migrants to these inhospitable parts of Russia, each family was eligible for a loan of up to 50 Roubles (GBP2 (two) or US$3½), which was a small fortune at the time or more if they ventured beyond Lake Baikal. Additionally once the railway was opened they were allowed a 75% reduction of the standard third class fare. Irregular migrants (peasants without any land in Western Russia) were offered free tickets.

The builders found the going easy from Samara to Ob'. From here on things became more difficult, the ground, which was normally frozen, and their primitive tools meant that progress was very slow, the undrained bogs of the Steppes presented other problems which held up the progress. The surface that the tracks had to be laid upon what was very variable foundations, from frozen solid to the track disappearing under two foot (60cm) of water when crossing boggy land. Because of this the route was redesigned so that the line was built into the side of hills, which gave a better and more stable setting. This involved extra time and expense by having to excavate cuttings into the rock and levelling steep gradients. Once the track reached Lake Baikal it was decided to postpone the construction around the lake and to cross it using the ferry. The ferry connection was between Listvianichnaia (on the west bank near Irkutsk) and Mysovskaia (on the east bank).

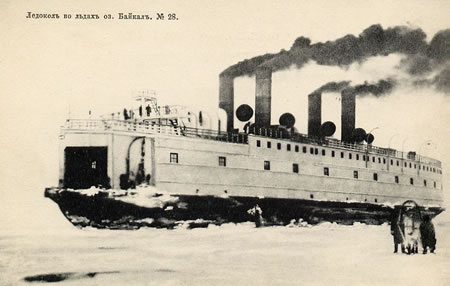

This ferry was specially built to break ice up to 3 feet 6 inches (107cm) thick and carry the whole train (a total weight of 4,200 tons) across the lake in one journey. The Newcastle-upon-Tyne (England) firm of Sir W. G. Armstrong, Mitchell and Company designed and built the ferry, which was named 'Baikal'. Once the ferry had been built and tested for seaworthiness, it was dismantled into kit form and the parts were sent by sea, river, and rail to Lake Baikal. The parts were assembled at a specially built dry dock on the lake, and the 'Baikal' was launched on 29th July 1899, and was operational until its retirement in 1918. This early retirement was due to the troops of the 'Czechoslovak Legion', returning from Russia's civil war, setting fire to it in the summer of 1918. In addition to this ferry a sister ship called the 'Angara' was built, using the same principle by the same English firm, and launched late in 1899. The 'Angara' was built to transport passengers only across the lake. The 'Angara' remained in service for over 60 years, and is now a floating museum on the lake.

Rolling stock ferry Baikal.

Before the eastern section of the line from lake Baikal to Vladivostok was built it was decided to approach the Chinese Government with the view to using land in Manchuria. The reason for this unusual request was that the terrain between Vladivostok and Mysovskaia was proving to be an arduous task. By utilising Manchurian land it would enable the port of Vladivostok to be reached by rail a lot quicker than the alternative route by sea. The negotiations with the Russian and Chinese governments were completed very quickly, and the Chinese agreed to the Russians building, operating, and policing a railway across their land. The line to Chita had already been laid, and as this was the nearest station to the Manchurian border with Siberia, allowed a more direct route to Vladivostok and Port Arthur. Port Arthur was an outpost of Russia based in Manchuria and a naval base with access to the Pacific Ocean. Port Arthur was unlike the other Pacific ports used by Russia, in that it remained ice-free all year round.

Passenger ferry Angara.

By 1902 the link between St. Petersburg and Vladivostok was complete, even though the journey crossed Chinese territory. The link between Vladivostok and Chita (totally on Russian land) was not completed until 1916, but construction continued while the link across Manchuria was being built. The railway, which ran across northern China, was called the Chinese Eastern Railway (CER) and is still in use today, it was thus named to distinguish it from the main Trans-Siberian Railway that was eventually to run totally on Russian land. The route was completed just in time for the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905. The Russo-Japanese War was an ideal test to prove how well equipped it was for transporting troops and materiel to Eastern Russia by rail. This test was passed with flying colours, with the usual occasional snag but proved its value as a rapid transit system. During the usual skirmishes between Russia and China, the Chinese Eastern Railway was taken over by the Chinese government in 1905 as reparations after the Russo-Japanese War.

The anticipated workforce required to build the railway was 30,000 navvies and 20,000 skilled and unskilled labourers. The requirement became more acute in the newly populated parts of Siberia, but the local peasants came to the fore and provided 80% of the heavy labour. Through the sparsely populated parts of Siberia and the worst of the weather the local prison camps supplied the labour. Because of the reluctance by the prisoners to work enthusiastically, progress was slow, but once it was known that prisoners were being used the law was changed. The law now allowed every prisoner 2 days off their sentence for every day they worked on the railway, and a 'wage' for the job. This resulted in a great improvement in its progress. The 'wage' for the prisoners varied between 8 and 18 Roubles per month (which was a fortune for the time) in addition to the reduction in their sentence. The work was hard and the conditions poor, but the thought of getting out of prison earlier than expected was a great incentive. In fact this incentive was so great that sickness averaged only 1% (one percent) of the total workforce. Even the death rate at 2% was very favourable in comparison to the other major construction projects going on around the world. One example is the Panama Canal, which had a death toll of 25,000, and a sickness rate well above 30%.

As was to be expected this railway was built by bribery to officials. The Russians have two proverbs regarding bribery, they are:

1. If they give, take; if they beat, flee.

2. A fool gives, a clever one takes.

The majority of the officials were of the opinion that they must use their wits if they intended to live on more than one income. Bribery was rife in many of the bureaucratic systems run by the government, and the employees took the view that this was no different to any other official office.

During the latter stages of the building of this railway it was noticed that the accounting systems used were many and varied. To this end Sergei Witte sent a memorandum to Kulomzin, which read:

'in essence … the construction of the Siberian Railway, an undertaking of such enormous importance requiring expenditures in the hundreds of millions of Roubles, is virtually being carried out without any record of its cost.'

In actual fact the ledgers recorded the amounts received and paid out. Due to overwork and understaffing, each section of the line used its own means of accounting. In some cases the 'books' were nothing more than a collection of receipts, etc. The inefficiency of the bookkeeping was reflected in the building of the railway. Because of this irregular array of accounting put the whole project into jeopardy, it was not until the intervention of Prince Meshchorskii that the project was continued. Prince Meshchorskii got the committee to issue a directive to the engineers 'To finish the railway at any cost'. This intervention gave some sort of credence to the variety of bookkeeping systems.

In the first year of operation the standard of service was extremely low, which resulted in an unreliable service. The length and size of the trains varied with the terrain, e.g. 36 carriages/wagons per train on flat sections and 16 on hills. The individual Station Masters handled all the trains on a station to station basis. One American passenger recorded a scene that was regarded normal for the service. 'Our train would draw up at a woodpile and a log house. The peasants would scramble off the train, build their fires, cook their soup, boil their tea, and still the train would wait. There was usually no baggage to be taken on or put off, no passengers to join us, no passing train to wait for … At last, for no particular reason, apparently, the Station Master would ring a big dinner bell. Five minutes later they would ring another. Then, soon after, the guard would blow his whistle, the train driver would respond with the engine whistle, the train driver would respond with the engine whistle, the guard would blow again, the driver would answer once more, and after this exchange of compliments, the train would move leisurely along, only to repeat the process two hours later at the next station'. This passenger noted that the stop took 17 hours.

There were no rules or timetables to be found even watches were scarce among the crew. The only thing that was certain was that the driver stayed with his locomotive for the duration of the journey. Towards the end of 1901 improvements to the line and management allowed an average speed of 25 miles per hour, and a reliable maximum journey time of 9 days. Prior to these improvements some parts of the line had a maximum speed of 13 miles per hour for passenger trains and 8 miles per hour for goods. One unusual rule was that the restaurant car on the train had to serve the meals by St. Petersburg time, even though the journey crossed seven time zones.

The economic impact of the railway was the greatest in Western Siberia, but this diminished as it continued eastward. Life for the original inhabitants of Siberia, between living 30 to 50 miles from either side of the line, was unaffected by the railway, and life carried on as it had for generations.

It is recorded that the total cost of the construction of the Trans-Siberian Railway, including the Chinese Eastern Railway, was 855 million Roubles. This cost was almost three times the original estimate of 350 million Roubles. To give some sort of comparison, the cost of building the Amur Railway was 390 million Roubles, the improvements and reconstruction cost 150 million Roubles. Once the resettlement costs, interest charges, and other invisible costs were taken into account the overall cost came to approx., 2,000 million Roubles, far more than the initial estimate of 350 million Roubles.

At the end of the day the Trans-Siberian Railway was an outgrowth of the historical use of the Russian government to control its border territories through centralisation and Russification. This urge had manifested itself continuously in Siberia since the time of Catherine II, and became more forceful in the period of reaction under Alexander III and Nicholas II. The railway represented a stage in the progression of Russian economic policy onwards increasing state intervention. Due to the lack of a Russian infrastructure within Siberia, the Trans-Siberian Railway was proffered as an immediate solution to the problem. The railway would also implement the forward policy that Russian strategists believed would be the best defence on their Asian flank. Along with some members of the professional societies, they proposed the construction of local railways and the improvement of Siberian rivers to promote trade and industry until each region could provide enough revenue to sustain and make profitable its section of a Trans-Siberian trunk (main) line. The regionalist intelligentsia, who voiced the hope that Siberia would thereby be able to withstand the onslaught of the centralising metropolis against its unique culture, shared these views.

The railwayisation of Russia was the most successful component of the State's industrialisation drive and the precondition of its modernisation. The linchpin in this project was Sergei Witte, who became a larger than life character and even overshadowed the Tsar on this project. If Witte had not had the enthusiasm, belief in the project, and the determination to see the project through to the end, most probably it would never have got passed the planning stage. The Russian State's attempt to assert its control over a sprawling geographical realm through colonisation has been the primary concern of its history from the Muscovite Grand Princes to the Politburo. The revolution of 1917 changed the face of Russia, but the continuity of certain patterns of economic development and economic enterprise is not difficult to see. The history of the Trans-Siberian Railway (The Great Siberia Way) exemplifies the predilections of Russian rulers in the age of industrialisation.

Ken Lewis