|

|

Incas

Incas and the Inca Empire

Extent and Organization of the Empire

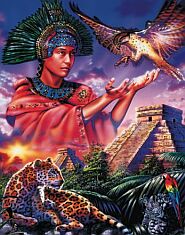

Centered at Cuzco, Peru, the empire at the time of the Spanish conquest (1532) dominated the entire Andean area from Quito, Ecuador, S to the Ro Maule, Chile, extending some 2,000 mi (3,200 km). Although the Inca showed a genius for organization, their conquests were facilitated by the highly developed social systems of some of the kingdoms that they absorbed, such as the Chim, and the established agrarian communities that covered the area of their conquest. The Inca empire was a closely knit state. At the top was the emperor, an absolute monarch ruling by divine right. Merciless toward its enemies and requiring an obedience close to slavery, the imperial government was responsible for the welfare of its subjects. Everything was owned by the state except houses, movable household goods, and some individually held lands. In addition to cultivating the land, the common people were drafted to work on state projects such as mining, public works, and army service. This obligation was known as mita. From well-stocked storehouses were drawn goods to support priests, government servants, special craftsmen, the aged and the sick, and widows.

The royal family formed an educated, governing upper nobility, which at the time of the Spanish conquest numbered around 500. To further increase government control over an empire grown unwieldy, all who spoke Quechua became an Inca class; by privilege and became colonists. Lesser administrative officials, formerly independent rulers, and their descendants were the minor nobility, or curaca class, also supported by the government.

For purposes of administration the empire was divided into four parts, the lines of which met at Cuzco; the quarters were divided into provinces, usually on the basis of former independent divisions. These in turn were customarily split into an upper and a lower moiety; the moieties were subdivided into ayllus, or local communities. Much as it exists today as the basic unit of communal indigenous society, so the ancient ayllu was the political and social foundation of Inca government. When a territory was conquered, surveys, consisting of relief models of topographical and population features, and a census of the population were made. With these reports, recorded on quipus, of the material and human resources in each province, populations were reshuffled as needed. Thus transplanted, and dominated by Quechua colonists, the subject peoples had less chance to revolt, and the separate languages and cultures were molded to the Inca pattern.

Religion, controlled by a hierarchy similar to the government hierarchy, emphasized ritual and organization. Heading the Inca gods was Viracocha. His servants were the sun, the god of the weather or thunder, the moon, the stars, the earth, and the sea. The sun god was foremost among these. Divination, sacrifices (human only at times of crisis), celebrations and ceremonies, ritual, feasts, and fasts were all part of Inca religion.

The Empire's Growth

Since the Inca combined much Aymara mythology with their own, their origin myth is obscure. The most common belief is that the legendary founder, Manco Capac (who seems to have been a historical figure), brought his people from mountain caves to the Cuzco Valley. During the early Inca period (c.1200-c.1440) the tribe gradually established its hegemony over other peoples of the valley and under the emperor named Viracocha (the name also of the supreme creator in Inca cosmology) allied themselves with the Quechua. However, it was not until the reigns of Pachacuti (c.1440-1471) and his son Topa Inca, or Tupac Yupanqui (1471-93), that the Inca made their great conquests. The present Ecuador (the kingdom of Quito) was subjugated by Huayna Capac, giving the empire its greatest extent and power. At his death it was divided between his sons, Huscar and Atahualpa, and a long civil war ensued from which Atahualpa emerged triumphant just as Francisco Pizarro landed on the shores of Peru and the Spanish conquest began.

Native Americans - Inca Chieftan and Leader Spanish Conquest

When Francisco Pizarro landed in South America in 1532, he was welcomed by Atahualpa. By strategem the conquistador lured the emperor into his camp, captured, and then executed him. Shortly thereafter (1533) Pizarro entered Cuzco. Although the Spaniards did not immediately subdue the Inca, the highly personal and centralized political structure of the Inca facilitated the Spanish conquest. Despite the heroic resistance carried on in many sections and the rebellion (1536-37) of Manco Capac, the conquest was assured. Under Spanish rule Inca culture was greatly modified and eventually Hispanicized . The natives were reduced to a subordinate status, and only in recent years have efforts been made to make the indigenous Peruvian population (about 50% of the total) an integral part of the national life.

Inca Agriculture, Engineering, and Manufacturing

Although the Andean area offered a diversity of plant domestication, the handicaps of terrain and climate presented severe obstacles. To overcome them, Inca engineers demonstrated extraordinary skill in terracing, drainage, irrigation, and the use of fertilizers. They lacked draft animals, but domesticated animals (the llama, the alpaca, the dog, the guinea pig, and the duck) were important to daily living; from the wild vicua, fine wool was sheared.

Without paper or a system of writing, the architects and master masons who designed and supervised the construction of public buildings and engineering works in such cities as Machu Picchu and the fortress of Sacsahuamn built clay models and, in actual construction, employed sliding scales, plumb bobs, and bronze and stone tools. Without wheeled vehicles for transport, the huge polygonal stone blocks for fortress, palace, temple, and storehouse were emplaced by ramp and rollers and were fitted with extraordinary precision. Wall corners were always carefully bonded. Adobe bricks and plaster were common, especially along the coastal desert. Buildings were usually of one story.

One of the most remarkable evidences of Inca engineering skill was an elaborate network of roads, which in many places still survives. Streams were crossed by a log or stone bridge, placid rivers by balsa ferry or pontoon bridge, and chasms by a breeches-buoy contrivance or by a suspension bridge that might be as much as 200 ft (60 m) long. Road sections were maintained by the nearest village, as were the shelters and military storehouses that were spaced a day's travel apart; a village also supplied messengers for its sector. These men, serving 15-day shifts, relayed messages about every mile. About 150 mi (240 km) could be covered daily, a distance that later took the Spanish colonial post 12 to 13 days to cover.

In the manufacture of textiles the Inca utilized almost every available kind of fiber and produced elaborate multicolored tapestries. In ceramics they achieved a fine-grained, highly polished, metallic hardness that stressed functional and utilitarian design. Mining was fairly extensive. Of the metals, copper and bronze were for public use; gold, silver, and tin were reserved for the emperor, the temples, and the upper nobility. Metallurgical processes included the techniques of smelting, alloying, casting, hammering, repouss, incrustation, inlay, soldering, riveting, and cloisonn.

Machu Picchu

This is a fortress city of the ancient Incas, Peru, about 50 mi (80 km) NW of Cuzco. It is perched high upon a rock in a narrow saddle between two sharp mountain peaks and overlooks the Urubamba River 2,000 ft (600 m) below; it was unknown to Spanish explorers. Discovered in 1911 by the American explorer Hiram Bingham, the imposing city is one of the few urban centers of pre-Columbian America found virtually intact. Perhaps the most extraordinary ruin in the Americas, Machu Picchu contains 5 sq mi (13 sq km) of terrace and construction, with over 3,000 steps linking it to many levels. It shows admirable architectural design and execution, although the stonework is not always as refined as in other Inca sites. The period of occupancy is doubtful, but legend indicates that the city may have been the home of the Incas prior to their migration to Cuzco as well as their last stronghold after the Spanish Conquest. See Hiram Bingham, Lost City of the Incas (1948, repr. 1969).

Bibliography

See chapters on the Inca in the Handbook of South American Indians, Vol. II (1963). For accounts by early historians, see Pedro de Cieza de Lon, The Incas (tr. 1959) and Garcilaso de la Vega, The Royal Commentaries of Peru (tr. 1966).

See also W. H. Prescott, The History of the Conquest of Peru (1855, repr. 1963); C. R. Markham, The Incas of Peru (1910, repr. 1969); P. A. Means, Ancient Civilizations of the Andes (1931, repr. 1964) and The Fall of the Inca Empire (1932, repr. 1964); Hiram Bingham, Machu Picchu: Lost City of the Incas (1948, repr. 1969); V. W. von Hagen, Highway of the Sun (1956); Louis Baudin, A Socialist Empire: The Incas of Peru (tr. 1961) and Daily Life in Peru under the Last Incas (tr. 1962); J. A. Mason, The Ancient Civilizations of Peru (rev. ed. 1968) and Alfred Mtraux, The History of the Incas (tr. 1970); G. W. Conrad and A. A. Demarest, Religion and Empire; The Dynamics of Aztec and Inca Expansionism (1984).

Native Americans - Inca Empire 1438 - 1525 |

|

|

|

|

Native American Nations

Native American Nations