|

|

Apache Apache

Apache Constitution

San Carlos Reservation

Native North Americans of the Southwest composed of six culturally related groups. They speak a language that has various dialects and belongs to the Athabascan branch of the Nadene linguistic stock, and their ancestors entered the area about 1100. The Navaho, who also speak an Athabascan language, were once part of the Western Apache; other groups E of the Rio Grande along the mountains were the Jicarilla, the Lipan, and the Mescalero groups. In W New Mexico and Arizona were the Western Apache, including the Chiricahua, the Coyotero, and the White Mountain Apache. The Kiowa Apache in the early southward migration attached themselves to the Kiowa, whose history they have since shared. Subsistence in historic times consisted of wild game, cactus fruits, seeds of wild shrubs and grass, livestock, grains plundered from settlements, and a small amount of horticulture. The social organization involved matrilocal residence, a rigorous mother-in-law avoidance pattern, and working for the wife's relatives. The Apache are known principally for their fierce fighting qualities. They successfully resisted the advance of Spanish colonization, but the acquisition of horses and new weapons, taken from the Spanish, led to increased intertribal warfare. The Eastern Apache were driven from their traditional plains area when (after 1720) they suffered defeat at the hands of the advancing Comanche. Relations between the Apache and the settlers gradually worsened with the passing of Spanish rule in Mexico. By mid-19th cent. when the United States acquired the region from Mexico, Apache lands were in the path of the American westward movement. The futile but strong resistance that lasted until the beginning of the 20th cent. brought national fame to several of the Apache leadersCochise, Geronimo, Mangas Coloradas, and Victorio. Remnants of the Apache now live in reservations in Arizona, where they number some 11,500. See G. C. Baldwin, The Warrior Apaches (1965); D. L. Thrapp, The Conquest of Apacheria (1967); Keith Basso and Morris Opler, ed., Apachean Culture and Ethnology (1971); J. U. Terrell, Apache Chronicle (1972). Cochise

c.1815-1874, chief of the Chiricahua group of Apache in Arizona. He was friendly with the whites until 1861, when some of his relatives were hanged by U.S. soldiers for a crime they did not commit. Afterward he waged relentless war against the U.S. army and became noted for his courage, integrity, and military skill. His friendship with Thomas Jeffords became the key to peace. In 1872, Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, the Indian commissioner, requested Jeffords to accompany him to Cochise's mountain stronghold. As a result of the peace talks, Cochise agreed to live on the reservation that Howard promised would be created from the chief's native territory. After the death of Cochise, however, his people were removed to another reservation. The southeasternmost county of Arizona is named for him. Geronimo c.1815-1874, chief of the Chiricahua group of Apache in Arizona. He was friendly with the whites until 1861, when some of his relatives were hanged by U.S. soldiers for a crime they did not commit. Afterward he waged relentless war against the U.S. army and became noted for his courage, integrity, and military skill. His friendship with Thomas Jeffords became the key to peace. In 1872, Gen. Oliver Otis Howard, the Indian commissioner, requested Jeffords to accompany him to Cochise's mountain stronghold. As a result of the peace talks, Cochise agreed to live on the reservation that Howard promised would be created from the chief's native territory. After the death of Cochise, however, his people were removed to another reservation. The southeasternmost county of Arizona is named for him. Geronimo

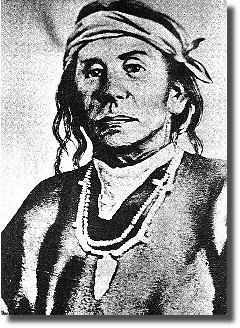

Geronimo's Wife, Taz-ayz-Slath, and Child

c.1829-1909, leader of a Chiricahua group of the Apaches, b. Arizona. As a youth he participated in the forays of Cochise, Victorio, and other Apache leaders. When the Chiricahua Reservation was abolished (1876) and the Apaches removed to the arid San Carlos Agency in New Mexico, Geronimo led a group of followers into Mexico. He was soon captured and returned to the new reservation, where he farmed for a while. In 1881 he escaped again with a group (including a son of Cochise) and led raids in Arizona and Sonora, Mexico. He surrendered (1883) to forces under Gen. George Crook and was returned to the reservation. In 1885 he again left, and after almost a year of war he agreed to surrender to Crook, but at the last minute Geronimo fled. His escape led to censure of Crook's policy. Late in 1886, Geronimo and the remainder of his forces surrendered to Gen. Nelson Appleton Miles, Crook's successor. They were deported as prisoners of war to Florida; contrary to an agreement, they were not allowed to take their families with them. After a further period in prison in Alabama, Geronimo was placed under military confinement at Fort Sill, Okla., where he settled down, adopted Christianity, and became a prosperous farmer. He became a national celebrity when he appeared at the St. Louis World's Fair and in Theodore Roosevelt's inaugural procession. He dictated his autobiography to S. M. Barrett (1906, repr. 1970). See biography by A. B. Adams (1971); studies by Britton Davis (1929, repr. 1963), John Bigelow (1958, repr. 1968), and O. B. Faulk (1969).

Mangas Coloradas [Spanish,=red sleeves], c.1797-1863, chief of the Mimbrenos group of Apache of SW New Mexico. Many of the Mimbrenos were massacred by trappers in 1837 as a result of the bounty for Apache scalps offered by the Mexican authorities. Mangas Coloradas, a natural leader because of his intelligence and size (unusually tall for an Apache, he was over 6 ft/180 cm), united the tribes, led them in a successful war of revenge, and cleared the area of settlers. When the Americans took possession of New Mexico in 1846, he pledged friendship to these conquerors of his Mexican enemies, but peace ended as the gold rush began. In 1851 a series of incidents culminated in hostilities when Mangas Coloradas suffered a humiliating flogging at the hands of some miners. Leading his warriors, he waged continuous warfare until he was finally captured and killed by Union soldiers in 1863. The name sometimes appears erroneously as Magnus Colorado.

Victorio d. 1880, chief of the Ojo Caliente [warm spring] Apache, at one time a lieutenant of Mangas Coloradas. When his people were removed from their ancestral home to the desolate reservation at San Carlos, Victorio bolted (1880) for Mexico with a group of followers. He and his people terrorized the border country with repeated raids and massacres, always managing to elude their pursuers. It took the combined efforts of the Mexican army, the Texas Rangers, and c.2,000 U.S. soldiers to defeat Victorio, a master strategist, and his warriors, who numbered less than 200. Victorio died in the battle. See D. L. Thrapp, Victorio and the Mimbres Apaches (1974). Victorio d. 1880, chief of the Ojo Caliente [warm spring] Apache, at one time a lieutenant of Mangas Coloradas. When his people were removed from their ancestral home to the desolate reservation at San Carlos, Victorio bolted (1880) for Mexico with a group of followers. He and his people terrorized the border country with repeated raids and massacres, always managing to elude their pursuers. It took the combined efforts of the Mexican army, the Texas Rangers, and c.2,000 U.S. soldiers to defeat Victorio, a master strategist, and his warriors, who numbered less than 200. Victorio died in the battle. See D. L. Thrapp, Victorio and the Mimbres Apaches (1974).

Ft. Sill Apache

TRIBE NAME: In their own language, the Fort Sill Apache identify themselves as members of one of the four divisions of the nation anthropologists call the Chiricahua (CHEER- uh-kou-uh) Apache tribe. The Chiricahua sometimes used the term Nd, meaning "people," to refer to themselves. The Fort Sill designation comes from the reservation where they were held as United States prisoners of war.

LANGUAGE: : The Chiricahua are one of the Apachean-speaking nations of the Southwest, Southern Plains and northern Mexico.

HISTORY: Southwestern New Mexico, southeastern Arizona and northern parts of Mexico were Chiricahua territory. In the 1500s, the Spanish invaded and began continuous efforts to force the Apache to submit. The tribe successfully resisted, although many lives were lost. In the mid-1800s, the United States claimed a large part of Chiricahua Apache territory, ignoring the tribe's rights. Thousands of miners, farmers and ranchers began moving onto Apache lands and driving the tribe out. When the people resisted, they were chased and assailed until they agreed to stay on reservations.

Some Chiricahua still resisted, however, so they were taken from their reservations and placed on a different tribe's reservation in Arizona. When a few of the Chiricahua refused to stay on that reservation, all the men, women and children were exiled to Florida as prisoners of war. They were kept there for two years before being moved to Alabama, and then to Fort Sill in Oklahoma Territory, which was to become their reservation when they were finally released. While at Fort Sill, they built homes and began raising crops and cattle. Forced to choose between allotments of farmland in Oklahoma or sharing the Mescalero reservation in southeastern New Mexico, of the 271 remaining tribe members, 187 went to Mescalero and 84 chose to remain in Oklahoma. The last of the Apache prisoners were released in 1914 after 28 years as U.S. prisoners of war. The smaller group who remained in Oklahoma are called the Fort Sill Apache.

CULTURE: Some of the Chiricahua Apache are also known as Warm Springs Apache. Today, most traditional ceremonies have been set aside and only a few remember the language.

LANDMARKS: Fort Sill Museum (Fort Sill).

Current tribal roll: 431

FORT SILL APACHE

Ruey H. Darrow, Chairperson

An Apache Medicine Dance

Apache Literature

Apache Men

Apache Women

Cochise ("Hardwood")

Geronimo - Goyathlay ("one who yawns")

History of the Apache

Land of the Ndee, Apachean People

Lipan Apache

Lipan Apache in Texas

The Handbook of Texas - The Apache

The Handbook of Texas - The Kiowa Apache

The North American Indian - Vol 1, The Apache

The Sunrise Dance

The Texas Apache

The White Mountain Apache Tribe

Identity

Who are these people? Their name for themselves is Tinde. But names that have been or are used by others than themselves are: - Mexican Spanish: Jicarilla , literally "little basket."

- Navajo: Be'-xai , or Pex'-ge

- Mescalero: Kinya-inde

- Kiowa: Keop-tagui , "mountain Apache."

- Picuris: Pi'-ke-e-wai-i-ne

- Mescalero: Tashi'ne

- Tesuque: Tu-sa-be'

Within the Jicarilla themselves are these smaller groups that claim

certain areas as their original homes: - Dachizhozhin : site of the present Jicarilla Reservation.

- Golkahin : south of Taos Pueblo.

- Ketsilind : south of Taos Pueblo.

- Apatsiltlizhihi : Mora .

- Saitinde : around what is now Espanola.

Though all of these are in New Mexico, the Jicarilla have been all through parts of southeastern Colorado, northern New Mexico, and adjoining areas of Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

LAND

Their contacts with the Spaniards began with Coronado in 1540 to 1542, perhaps as the Querechos , whom the later Spanish explorers called Vaqueros.

Hostilities began almost at first contact with the Spaniards, and though a Spanish mission was attempted near Taos in 1733, it was short-lived. Here is a general time table of the Jicarilla's relationships with the new landlords. - 1853: A group of 250 Jicarilla were settled on the Puerco River, but a treaty with the governor of New Mexico was not honored by him and war broke out again.

- 1854: Jicarillas are defeated by the United States Army.

- 1870: The Jicarilla are living on the Maxwell grant in NE New Mexico, but it is sold out from under them.

- 1872 - 1873: The U.S. tries to move the Jicarilla to Fort Stanton.

- 1874: A reservation of 900 square mile is established at Tierra Amarilla, in the north of New Mexico Territory. This lasts less than four years.

- 1878: An Act of Congress is passed to force the Jicarilla south, they refuse, and their annuities are canceled. One version of history has called the resultant acts by the tribe as "resorting to thievery."

- 1880: Act of 1878 repealed, new reservation on the Navajo River.

- 1883: Jicarilla moved to Fort Stanton.

- 1887: On February 11, an Executive Order creates a reservation in the Tierra Amarilla area in northern New Mexico.

- 1908: A southern area is added to the reservation.

From an estimated population of 800 Jicarilla in 1845,

the tribe today numbers about 1,800. |

|

|

|

|

Native American Nations

Native American Nations