Geoffrey

Chaucer

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Literate English (4) | |||

| Perhaps the most notable thing about written Old English is that it does not make one bit of sense to us. It's not just eccentricities of spelling, but completely unfamiliar words. The various dialects also have large differences. Minor local variations of pronunciation and vocabulary have become lost to us, but it is a fair bet that the average villager could only converse truly fluently with a fairly limited proportion of the population. | |||

| There is no particular occasion on which Old English became Middle English, but by the 14th century the language had changed considerably. It is almost comprehensible to us, if we read aloud, ignoring the spelling, and skipping over the odd unfamiliar word. | |||

|

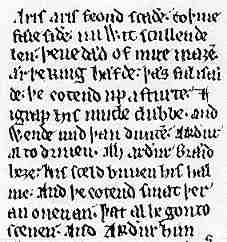

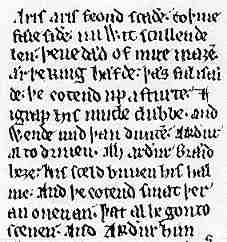

This example, from the early 13th century, shows something of the transition, as well as exemplifying the sliding social scale of language and its changes. The segment is from Layamon's Brut, a translation from the Norman French of the Roman de Rou, which in itself incorporated a translation from the Latin of Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain. This segment is a highly legendary bit of the King Arthur legend, where he battles a giant near Mont St Michel. | ||

| Segment from an early 13th century version of Layamon's Brut (British Library, Cotton Caligula A IX, f.155). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1906) | |||

| The language of this sample is still seriously incomprehensible, although bits jump out. The line igrap his mucle clubbe suggests something ugly about to happen! The Brut became a defining document of Englishness, despite its linguistic parentage, and was used as the basis for later English language chronicles which were added to it. Arthur, the great British hero battling the Anglo-Saxons, transformed into Arthur the prototypical English king. Strange really. | |||

| By the time of Chaucer, England was still a country with linguistic social stratification, but the nature of both English and French had changed. In fact, it was a bit hard to know just what was England and what was France as bits of territory went back and forth between them and the aristocracy seemed to change sides depending on what side of bed they got out of in the morning. |

|

||

|

Geoffrey

Chaucer

|

|||

| Aristocratic families in England still spoke French. Their increasing taste for fancy volumes of vernacular literature had also largely been satisfied by works in French. Now it was more likely to be the French of Paris rather than the old Anglo-Norman dialect, as they were likely to have been hobnobbing around with other aristocrats from France. As education crept slowly down the social scale, children from English speaking families also learned French in school. However, during the course of the century there developed an increasing demand for, or acceptance of, English literature and Chaucer, of course, was able to produce his famous bestsellers. | |||

|

The beginning of The Geste of Kyng Horn, early 14th century (British Library, Harley 2253, f.83). (From The New Paleographical Society 1912) | ||

| While professional authors and poets like Chaucer or John Gower were writing some works in English, educated lay people were taking an interest in copying down compilations of all sorts of things that interested them. The above segment is of an English work probably derived ultimately from the oral tradition, although known in several manuscript copies. It is in a codex, written almost entirely in one hand, of assorted works in English, French and Latin. Linguistic stratification into church, aristocracy and common laity was evolving into multilingualism, at least for the literate classes. | |||

| Significant Latin works were also being copied into English. John of Trevisa undertook the English translation of such whopping great Latin works as Higden's Polychronicon and Bartolomeus Anglicus' De Proprietatibus Rerum. Works originally designed for contemplation and preaching inspiration by the clergy were getting a new life. | |||

| 1362 was a big year for the official recognition of English in matters of law and government. The Statute of Pleading was enacted in Parliament, ensuring that all pleas in the King's courts should be conducted in English, although in fact this did not happen in the common law courts, which continued to use French. Records of court proceedings continued to be kept in Latin and those of Parliament in French. In that year also, the Parliamentary clerks recorded, in French, for the first time that Parliament had been addressed in English. It probably wasn't the first time it had happened, but suddenly it was an issue of note. As far as legal documents issued by the Chancery were concerned, formal charters were in Latin, but less formal documents such as writs or warrants could be in the vernacular, at this stage still French. | |||

|

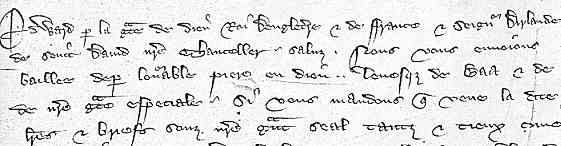

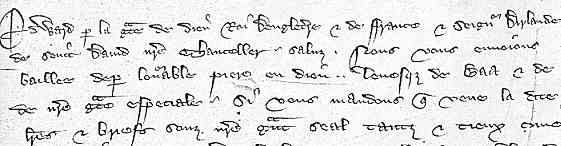

|||

| This is the top left segment of a chancery warrant of 1349, ordering letters and writs under the great seal to the Bishop of Bath and Wells. (London, National Archives C.81/339/20343). By permission of the National Archives. | |||

| In the above example of a chancery warrant under Edward III, the script is a cursive chancery hand. The language is French. | |||

| While English retained its Germanic structure and most of its vocabulary, some words were absorbed from French. There were deliberate and self-conscious borrowings by the new generation of English litterati in order to create a more elegant written language. Other absorptions just happened. Sometimes these reflected the social differences embodied in the languages. The most quoted example for this is the use of words of Anglo-Saxon origin for domestic animals (cow, sheep, pig) and those of French origin for their meat (beef, mutton, pork). While the French speaking nobles consumed the product, the English speaking agricultural workers who tended the beasts had to make do with pease porridge in the pot, nine days old. | |||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

|||