If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames).

| Literate English (3) | ||

| Written texts in Old English can be assigned to four major dialects: Northumbrian, Mercian, West Saxon and Kentish. The northern dialects particularly were influenced and infiltrated by the North Germanic branch of the Germanic languages through the Danish invasions. The florescence of English written texts and translations from the Latin that is traditionally associated with the court of King Alfred made the West Saxon dialect the most usually encountered in the later Anglo-Saxon period. The detailed study of place names has augmented the study of written texts in examining linguistic patterning over the landscape. | ||

| A few terms from Latin entered the vernacular in relation to matters of the church. Legal process was an oral procedure, carried out at local level according to laws passed on by oral tradition. When the later Anglo-Saxons wished to commit a legal procedure, such as establishing the ownership of land, to writing, it was carried out through a form of Latin diploma. These were evidently drawn up and written by literate monastic scribes. |

|

|

| The Anglo-Saxon Charters web site can tell you all you possibly need to know about these. | Another one of those schoolbook images depicting Anglo-Saxon justice. They make it look very melodramatic. | |

| It appears to be in the time of Edward the Confessor that the vernacular was first used for legal documents, in the form of the charter or writ. These concise documents, authenticated with the great seal, formed a basis for much that came later and give us a glimpse at Old English legal language. | ||

|

||

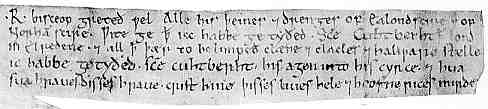

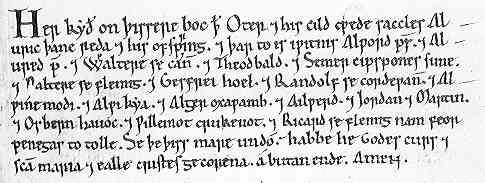

| An example of an Old English charter or writ, from 1106-1128, of Ranulf Flambard, bishop of Durham (Durham Cathedral 2da 1ma Pont. No. 9). (From the New Palaeographical Society 1904) | ||

| The above example, in which a bishop grants lands to Durham cathedral, is an interesting anachronism in that it dates from after the Norman Conquest, and furthermore is in an ecclesiastical context, so you would expect it to be in Latin. Odd, and just goes to show that you can't make absolute rules about anything. It shows how short and sweet these things were, and how they used insular minuscule script when writing in English, as opposed to the Caroline minuscule they used for Latin. | ||

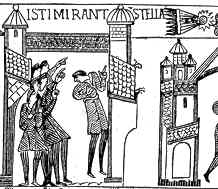

| The year 1066 was a highly significant one. Halley's comet appeared for one thing. As far as England was concerned, yet another wave of foreign speaking invaders landed on their shores and refused to go home. |

|

|

| Halley's Comet in 1066, as depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. | ||

| The Norman aristocracy claimed descent from the Vikings. While they had adopted French ways and spoke a version of French, it was not the French of Paris, but a dialect which had undergone some Germanic influence. It is referred to as Anglo-Norman or Norman French. | ||

|

||

| Much later medieval effigy representing Rollo, the Viking ancestor of William the Conqueror, in Rouen Cathedral. | ||

| Unlike the Anglo-Saxon invaders, they did not supplant the language of the existing population. This linguistic invasion had a social dimension, as the imported aristocracy and those who aspired to it spoke Norman French, and the lower orders, freemen and serfs, spoke English. Latin was firmly re-established as the language of the church and of legal documents, although the form of the Anglo-Saxon charter or writ was retained, but translated into Latin. Written English dips under the radar for a while at this time, although it surfaces here and there. | ||

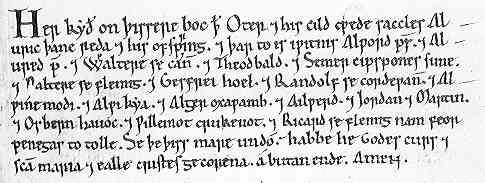

| Some Old English terms from the Latin section of a bilingual charter of Henry I, of 1123 (British Library, Campbell Chart. xxi 6), by permission of the British Library. | ||

| Some Old English legal terms occasionally appear in Latin charters, indicating rights and privileges that have existed from the previous linguistic regime. The fact that they often appear in alliterative pairs, with a certain rhythm and metre to them, suggests that they are formulae remembered from oral tradition. | ||

|

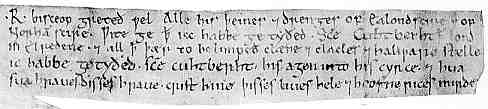

Extract from early 12th century manumissions of serfs, now bound in the front of the Exeter Book (Exeter Chapter Library, No. 3501). (From The New Palaeographical Society 1903) | |

| The above example is one of a set of manumissions of serfs that were originally entered into a gospel book, but later rebound into a codex of Anglo-Saxon poetry. Vernacular gospel book entries are found from the early days of literate legal process, and represent a form of oath taking, recorded in the most sacred artifact. The text makes reference to kissing on the book, and that God's curse will be on any person that undoes this act. | ||

If you are looking at this page without frames, there is more information about medieval writing to be found by going to the home page (framed) or the site map (no frames). |

||