|

The

African-American Census

|

||

|

[

H I S T O R I C A L . C O N T E X T ]

|

||

In 1837, the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and

for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage and for Improving

the Condition of the African Race, more commonly referred to as the Pennsylvania

Abolition Society (PAS), appointed the Committee to Visit the Colored People.

The Committee was tasked with conducting a census of the entire black population

in Philadelphia and the surrounding suburbs. Data for the census was collected

in 1837 and encompassed 3,652 households and 13,591 individuals. The findings

were published in 1838, which, in addition to the raw census data, included

an "Analysis of Census Facts" that provides a summary of the data

collected. The manuscript of the census is composed of four volumes and though

it is still owned by the PAS, it is held on deposit at the Historical Society

of Pennsylvania. Further information regarding some historical publications

that pertain to the census findings is presented in the section "Additional

Resources."

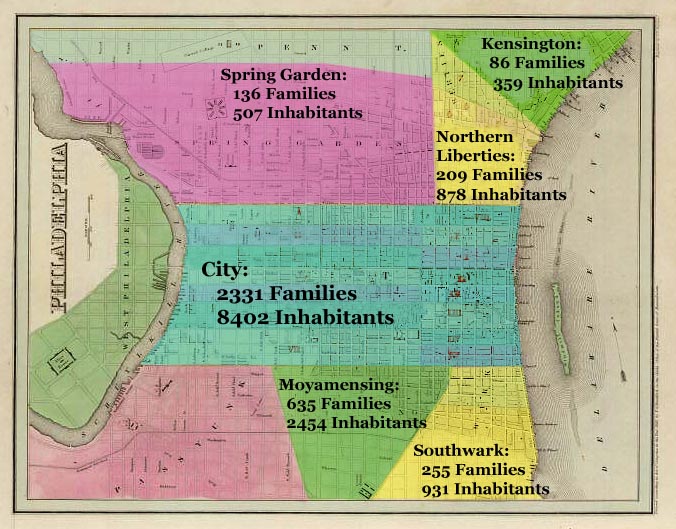

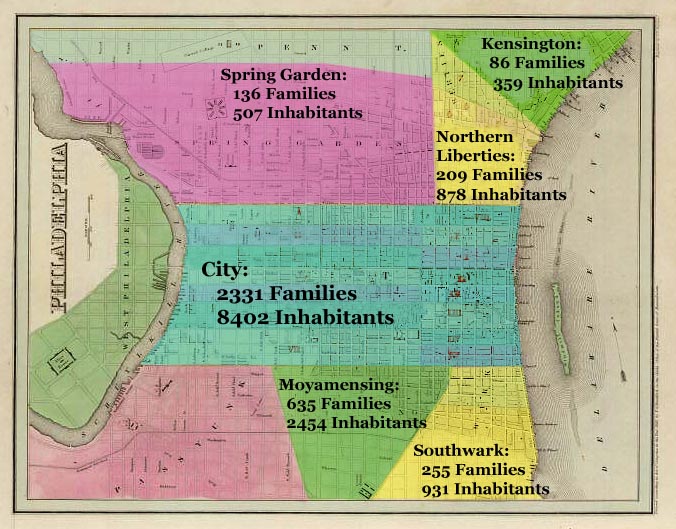

The map of Philadelphia below is based on one taken from S.G. Goodrich and Thomas

G. Bradford's World Atlas of 1841 and depicts the City of Philadelphia

and its suburbs. The African-American Census of 1838 includes the City of Philadelphia,

Moyamensing, Southwark, Northern Liberties, Spring Garden, and Kensington. For

each of these areas, the map notes the number of families as well as the total

number of individuals living in that area. In the City of Philadelphia, we see

the highest population of African-Americans with 2,331 families and 8,402 inhabitants.

Moyamensing follows the City with the second largest population composed of

635 famlies and 2,454 inhabitants. In Southwark, there were 255 families and

931 inhabitants; in the Northern Liberties, 209 families and 878 inhabitants;

in Spring Garden, 136 families and 507 inhabitants; and in Kensington, 86 families

and 359 individuals.

S.G. Goodrich and Thomas G. Bradford. Philadelphia 1841. World Atlas.

From the David Rumsey Collection.

Note: Though the census preceeds the publication of this map, the political

boundaries shown here remained consistent.

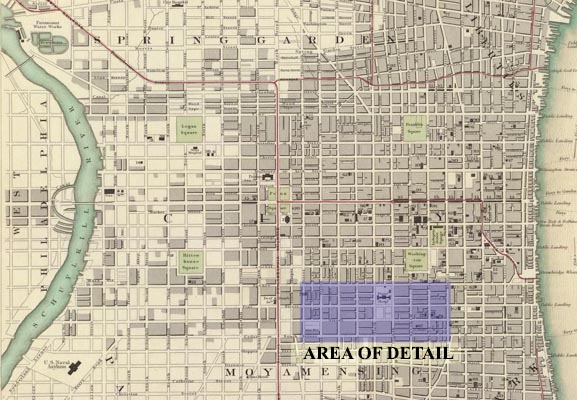

In light of the significantly higher population of African-Americans who lived within the City limits, this project focuses on households in this area. Within the city itself, the largest concentration of African-Americans was found between Fourth and Twelfth Streets and between Spruce and Cedar (now South) Streets. The map below, which is based on a map published by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowlege, shows this area of concentration highlighted in purple. The second map provides greater detail of this area.

Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. Philadelphia 1840. World

Atlas.

From the David Rumsey Collection.

The census itself contains a wealth of information with regard to such topics as occupation, real estate, and church membership. Although the specific wording that the census-takers used varies slightly between volumes, the information requested from each household remains consistent. Information was organized under the following headings:

In order to understand the census of 1838 fully, it is necessary to consider the political changes occurring in Pennsylvania in 1837. At the 1837-1838 convention to amend the Pennsylvania state constitution, there was signficant debate surrounding the issue of whether or not free blacks should continue to have voting rights. The constitution that existed prior to the convention was ambigous with respect to the right of blacks to vote. In her work Philadelphia's Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787-1848, Julie Winch describes this ambiguity: "[The Constitution of 1790] provided simply that citizens over the age of twenty-one who had lived in the state for at least two years and been assessed for a county tax could vote. The only stipulation was that voters had to be 'freemen'" (135). As Winch also describes, however, there was controversy regarding whether or not the term "freemen" applied to blacks. To remove the ambiguity that surrounded the question of blacks' voting rights, Benjamin Martin, a delegate to the Reform Convention to ammend the state constitution, proposed that voting rights be limited specifically to whites. The PAS actively lobbied to prevent this change to the constitution, and the African-American Census was an important component of these efforts. According to both Thomas Hershberg and Gary Nash, historians of African-Americans in Pennsylvania, the census was intended to demonstrate that blacks were valuable contributors to their communities. However, despite the efforts of the PAS and of other activists, the constitution, which was ratified in October of 1838, excluded blacks from the franchise. African-Americans in Pennsylvania would not gain legal voting rights again until after the Civil War. Considering this political context with respect to the African-American Census of 1838 greatly enriches one's readings and understandings of the document.

In addition to the census completed in 1838, two later censuses also were taken

in 1847 and in 1856. The 1847 census, however, was conducted under the sponsorship

of the Society of Friends. Taken together, the three censuses present a unique

research opportunity to trace changes over time. This could, for instance, allow

a researcher to trace families across generations, to examine patterns and changes

in church membership, or to observe changes in the spatial distribution of blacks

in the city. The section "Additional Resources" provides some examples

of how more contemparary authors have utilized the information documented in

the census.

Sources

Hershberg, Theodore. "Free Blacks in Antebellum Philadelphia: A Study of Ex-Slaves, Freeborn, and Socioeconomic Decline." African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting Historical Perspectives. Ed: Joe William Trotter Jr. and Eric Ledell Smith. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1997. 123-147.

Nash, Gary. “The Dream Deferred.” Forging Freedom: The Formation of Philadelphia’s Black Community, 1720-1840. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1988. 246-281.

Winch, Julie. Philadelphia's Black Elite: Activism, Accommodation, and the Struggle for Autonomy, 1787-1848. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 1988. 135.