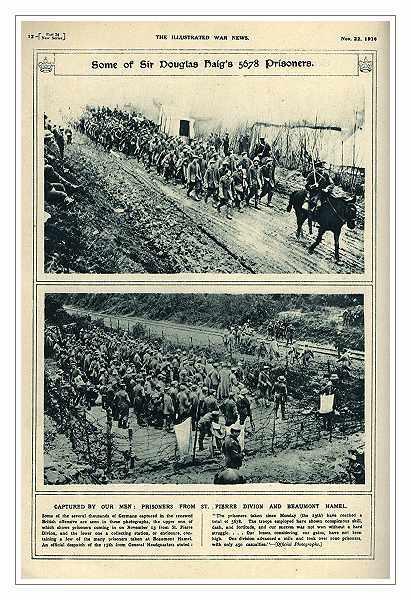

from ‘the War Illustrated’ 25th August 1917.

two pages from a British magazine

a Day in a Prisoners' Cage at the Front

The prisoners cage for the —th Army Corps lay about two hundred yard's to the left of the main road. My car used to pass it every day on the way to the front from the Press Correspondents' Camp in ——. Often I was tempted to mate a stop and pay it a visit, and at last one day I did so, meaning to stop a few minutes. Instead, I stopped for some hours, so interesting was the life of the place.

A "corduroy" road (made of logs, laid transversely) led from the main road across, open fields, without hedges, to the "cage." It was a rectangular, three-acre field enclosed by a high, double rampart of barbed-wire. Between these two ramparts was a space of perhaps ten yards. Within it a sentry, with bayonet fixed, patrolled each side of the rectangle. In addition two sentry-boxes, mounted on platforms at a height of about ten feet, stood at diagonal corners of the enclosure. The sentries thus posted could watch the four sides of the enclosure, each sentry having a clear view of two sides of the rectangle. An electric cable ran round the cage with lamps at intervals, so that at night the intervening space between the two barbed-wire ramparts could be thrown under a glare of light. On the farthermost side of the cage from the road were the only entrances to it, and facing these entrances were the wooden huts wherein lived the guard and the British major in charge of the camp.

Warders and Prisoner Quarters

He welcomed me in the little wooden but that served him for home, office, and reception-room all in one. It was no more than ten feet by nine, and, like most British Army huts, smelt strongly of creosote. A small stove of American pattern supplied heat, and at the same time served to keep hot a pot of tea which an orderly brewed for us. We drank it from iron cups after pouring in milk from a tin. There was buttered toast, too, on a tin plate. First he showed me the tents and huts in which his guard of about forty men lived. They had their own kitchen hut, and also a recreation hut, an invaluable asset in this remote place, seven miles from anywhere. They were garrison, duty troops and Mostly men of forty and thereabouts.

As I looked out of the major's hut window, trimly covered with a curtain the prisoners' camp seemed singularly empty. A few figures dressed in the German grey-blue were to be seen moving about the long lines of tents, and about the open, iron-roofed buildings in the centre of the camp, but there could not have been more than twenty or thirty at the most. "The others are out at work," said the major ; "they are mending the roads about a mile away, but " — here he looked at the little American clock that stood on the window ledge — "they should be back any moment now."

He jumped up from the packing-case on which he had been sitting — having given the one chair of the place to me — and looked out of the window. "Yes, here they come !" he said.

Marching four abreast along the corduroy road came several hundred German prisoners. They carried picks and shovels over their shoulders. They were dressed for the most part in the grey- blue tunics, trousers, little flat caps, and the big top-boots of the German Army. Most of them had overcoats too, generally of a dark blue, but into each coat had been let a round, circular patch of some bright-coloured cloth, generally red, to make a conspicuous mark. Some of the prisoners wore khaki puttees and boots instead of top-boots, and the major told me that these had been supplied by the British Army to men who had not had suitable footwear of their own. Overcoats also had been supplied in many cases, On each flank of the marching column were the British guards in khaki — looking wonderfully spick and span both in walk and in appearance compared with the untidy slouch of the prisoners.

The Company Sergeant-Major

By their side marched also an immense German, over six feet in height and broad as an ox. He was in neat, dark-blue uniform with shining buttons. His collar was trimmed with gold braid, his sleeves with scarlet. This was the German prisoners' "Feldwebel," a rank equivalent to our British Army's rank of company sergeant-major. All orders to the prisoners were transmitted through him. He was responsible to the major for the internal discipline of the camp.

Whenever an order had to be given to the prisoners it was he who gave it. With a roar like a bull's he issued, in German, the commands passed on to him by the officer of the guard. Simple routine orders he shouted on his own initiative. "Right wheel, left wheel, halt, front," etc. It was he who thus piloted the prisoners to 'the cage gate' and brought them in a double rank facing the major's little office. Under his commands they drilled beautifully, like one man for time and smartness. Then he turned and gravely saluted the major who was watching. The major returned the salute.

Fair to Outward Seeming

The prisoners had stacked their picks and shovels in a corner near the huts, and had formed up again two deep, facing their "Feldwebel." He made them salute the major, then left wheel, and in a minute they were ''marching through the gate of the cage which was just wide enough to admit them two abreast. At each side of the gate was a British sergeant who counted in a loud voice as the prisoners went in "Two, four, six, eight !" and so on it went, in a steadily-mounting total. The big "Feldwebel" stood by watching the men go through. Here I had a talk with him in German. He glanced at my uniform, clicked his heels, and saluted gravely, then in answer to my questions he told me stiffly that he was from Silesia, in Eastern Prussia, and that he had been promoted to "Feldwebel" in the fourth month of the war. His father, he said, was a corn-miller. He himself was married and had three children,

As I happened to know well the .part of Germany in which he lived he seemed quite interested and talked with much less stiffness. Once or twice he smiled and became quite human.

Looking at his red-brown cheeks, clear, well-spaced eyes, and strong frame I was beginning to think what a decent sort of soul he was when I received the rudest shock. His men had been marching through the gate in twos. Suddenly one man, a little fellow with weak frame and hanging head, a man who looked to me but half-witted, managed to get into the marching line alone instead of with a comrade. This might have deranged the counting. He was nearing the gate when the "Feldwebel," turning his head away from me, caught sight of him.

Native Brutality of the Hun

He bounded from me with three great strides and bawling the word "Heraus !" (Get out of it'), he struck the wretched little man a blow under the ear that would have felled an ox. The little man went over and fell quite three yards away, lay still on the grass for several seconds, then scrambled to his feet and tottered to the back of the column. Not one of the Germans took any notice. The "Feldwebel" came back to me quite unruffled, and would have resumed the conversation where he left it but I had no patience. "You dirty brute," was all I could say and then I left him. For the simple fault of merely falling out of line he had all but killed a man. If that is the behaviour of a "Feldwebel" towards a fellow-prisoner in a British cage how must they treat their men during the excitements and difficulties of battle ?

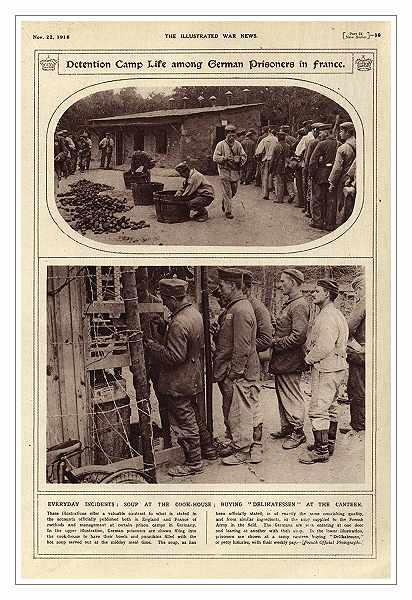

Once inside the cage the prisoners went to their separate tents and then to the wash-houses in the centre of the camp, where they removed the stains of the day's work. Soon they were mustering in a long line to receive their rations. The line marched slowly past their store-house door. Each man received a raw herring and half a loaf, and had his pannikin filled with hot meat stew. Some brought a plate for their herrings, but most of the prisoners clutched them in their fists.

Supper and Music

The herrings were taken off to the kitchens within the prisoners' camp and cooked by Germans who had been chosen by their comrades to stay in the camp all day and to cook meals while the others went out to work. Quite good kitchens, drying-sheds, and bath-rooms had been set up. The prisoners did the building, but the Army supplied the material.

Soon the evening meal was over. The men busied themselves mending their clothes or writing letters. (They are allowed to write regularly to their homes in Germany.) Others produced musical instruments which, by some queer magic, they had managed to have about their persons when captured and when dark came the camp was resounding to the lugubrious singing of "Mein lieber Augustin," "Pipchen, du bist mein Augenstern," and other favourite German melodies.

I spoke with many of the prisoners, and asked them whether they were comfortable. All said they had nothing to grumble about. It was much better, some said, than being in the trenches. Remembering the "Feldwebel's " methods I asked how they got along with him, and one of them told me that he was "No more of a pig than all 'Feldwebels.' "

from 'the Illustrated War News'

see also : Great Escapes of the Great War : 4 Personal Accounts