Emilienne Moreau - a Civilian Heroine

We in America find it possible to read with calm pulse and an attitude of cold, reasoned impartiality the stories that are written in red blood and heroic action by real participants in the great war. Their language, like their viewpoint, seems to us extreme, violent, embittered. Yet, inasmuch as the presence of stern reality, which colors viewpoint and language, is the same that inspired the valorous action itself, we submit, exactly as it came from Paris, this article, which recounts at first hand the desperate courage ef Mile. Moreau.

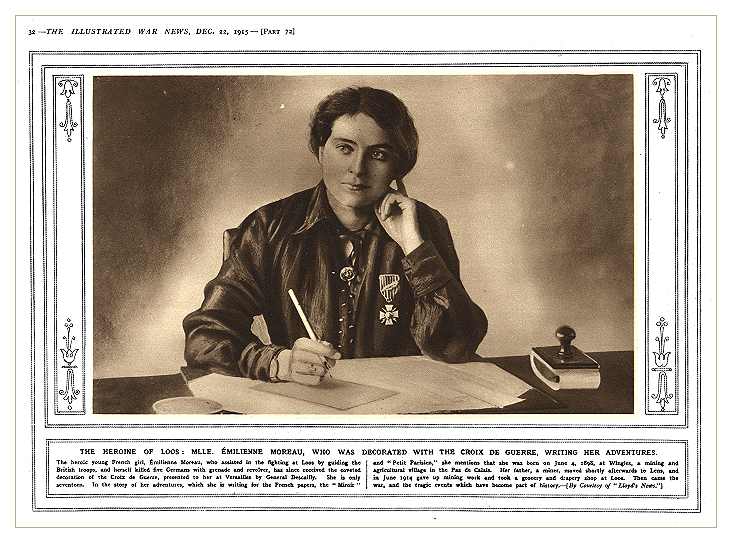

IN the musty archives of the. French Government she is merely Emilienne Moreau, youngest of her sex to have achieved mention in Gen. Joffre's Order of the Day and the right to wear upon her breast the Cross of War. But to thousands upon thousands of French and British soldiers, she is the Jeanne d'Arc of Loos — whose valiant spirit won back Loos for France.

The Official Journal has only this to say about Emilienne Moreau:

"On Sept. 25, 1915, when British troops entered the village of Loos, she organized a first-aid station in her house and worked day and night to bring in the wounded, to whom she gave all assistance, while refusing to accept any reward. Armed with a revolver she went out and succeeded in overcoming two German soldiers who, hidden in a nearby house, were firing at the first-aid station."

No mention is made in the official record of the fact that she shot down the two Germans when their bayonets were within a few inches of her body; and that later on she destroyed, with hand bombs snatched from a British grenadier's stock, three more foemen engaged in the same despicable work.

Nor is it set forth how, when the British line was wavering under the most terrible cyclone of shells ever let loose upon earth, Emilienne Moreau sprang forward with a bit of tri-colored bunting in her hand and the glorious words of the "Marseillaise" upon her lips, and by her fearless example averted a retreat that might have meant disaster along the whole front. Only the men who were in that fight can fully understand why Sir Douglas Haig was right in christening Emilienne Moreau the Joan of Arc of Loos.

All this happened during the last great offensive of the allies in Artois, between Arras and La Bassee. For almost a year before Emilienne Moreau, who is now just seventeen, had lived in Loos under the rule of the invader.

During almost all of that time the village had been under the allies' artillery fire. Yet neither she nor her parents made any attempt to move to a safer place. Their home was in Loos, and some day, they felt sure, the Germans would be driven back. They were always short of food. Sometimes they faced death by starvation, as well as by bombardment.

But they remained, and Emilienne even contrived to continue the studies by which she hoped to become a school teacher.

Like the Historic Maid of Orleans, the maid of Loos has not only the warlike but the diplomatic genius. Despite the dangers she faced because she was both young and comely, she succeeded in gaining the Germans' confidence to such an extent they entrusted to her much of the administration of what remained of the village.

Children whose parents had been killed or taken away as prisoners were put in her care, and she was permitted to give them what little schooling was possible under the conditions. She was at the same time the guardian angel of her entire family; for her father, a hot-blooded old veteran of 1870, frequently put them in danger of drastic punishment by his furious denunciations of the enemy. His chagrin so embittered him that, what with that and scanty nourishment, he died. Then Emilienne became the protectress and sole support of her mother and her ten-year-old brother.

She buried her father with her own hands, in a coffin built by her brother and herself, there being neither undertakers nor carpenters left in Loos. And she continued to go quietly about her many tasks, still stifling within her the resentment against the ever-present "Boche," until there came that glorious day when she knew the allies' offensive had begun.

For three days the girl huddled in the cellar with her terror-stricken mother and little brother waiting for the end of that awful cannonade which she realized was destined to bring the British to Loos.

Every minute of those seventy-two hours she and every one of the handful of old men, women and children in the village were facing death, but she told an English officer after it was all over that to her it had been the happiest time since the German occupation began.

As soon as Emilienne heard among the deep notes of the guns the sharp reports of rifles she rushed out into the street and into the midst of the first phase of the battle. The British were driving the Germans before them at the point of the bayonet, but there was still much desperate activity going forward with bombs and hand grenades, for remnants of the German main line were ensconced strongly in various fortlets and bombproofs scattered among the trenches. On every street of Loos the wounded lay thickly.

Emilienne saw there was only one way she could help them, and so very swiftly she turned the Moreau house into a miniature hospital, and with the aid of the British Red Cross men she tended as many wounded as she could drag from the maelstrom of the fight.

It was when the first lull came that she detected the firing upon her first-aid station. How she followed and shot down the two Germans responsible for this wanton attack is narrated in the official report. Not long afterward she located three more in the act of perpetrating the same outrage, and this trio she despatched with grenades borrowed from a British sergeant.

Although it was the first time in the war that a woman had fought with hand bombs, such was the confusion of the battle that her brave exploit passed unremarked until it was revealed by a special correspondent of a Paris newspaper, the Petit Parisien, who got the story from British soldiers. From the same source all France learned that because a young girl had been courageous enough to sing the "Marseillaise" amidst the din of battle the British troops had ceased to falter in their advance, and the village of Loos had again become part. of France.

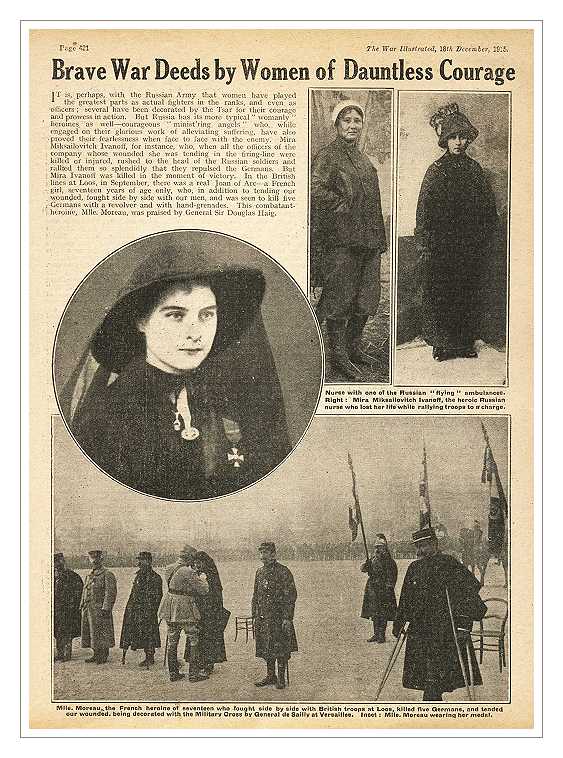

The spirit of Jeanne d'Arc, which inspired Mile. Emilienne, is abroad, not only in her native France, but among the women of France's allies as well. Their heroines emerge in the war news day by day — sometimes individually, sometimes en masse.

There is an actual "Regiment de Jeanne" — a whole corps of French and Belgian women commanded by Mme. Louise Arnaud, who has obtained permission from the War Minister to put them in uniform. The corps is for general service at the front, one-third of the members to be enrolled as combatants, drilled and armed like ordinary soldiers, and all able to ride and swim.

Mme. Arnaud is the widow of an officer who was killed in the war. Her father was a merchant ship captain of Calais. Her new "amazon" command is to be officially designated the "Volunteer Corps of French and Belgian Women for National Defence."

Servian and Russian women are fighting alongside the men in the trenches along the Balkan and other fronts to-day. Mme. Alexandra Koudasheva, a distinguished Russian literary lady and musician, has been appointed Colonel of the Sixth Ural Cossack Regiment of the Czar's army, for her valiant services in the field. England has the London Women's Volunteer Reserve, headed by Col. Viscountess Castlereagh, which drills regularly at Knightsbridge Barracks and has reached a high state of efficiency, both in manoeuvers and the manual of arms.

Many of the English women soldiers are assisting the authorities as guards of railway bridges and other points of military importance in out of the way parts of the country.

The British Government shows no disposition to make use of the women in fighting, but many of the women themselves are eager to fight. The "suffragettes" have made themselves remarkable by demanding a more vigorous prosecution of the war.

The reports generally agree that the women fight with great bravery and some even say that they display greater bloodthirstiness than men. This is an interesting question which has hardly yet been settled, although psychologists have furnished an explanation why we should expect them to be more ferocious. They are of course more emotional and when circumstances such as an attack on their homes or children force them to overcome their womanly instincts and resort to fighting, they throw away all restraint and fight with mad, instinctive ferocity.

from an American newspaper

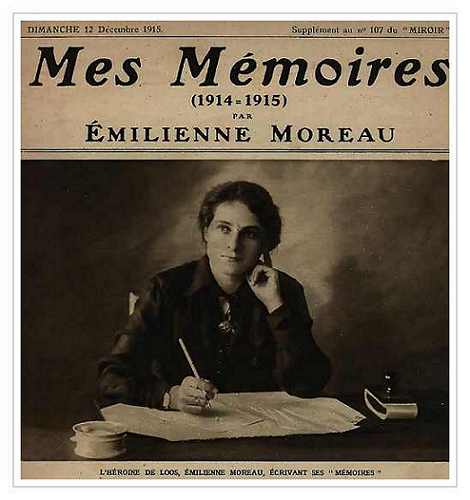

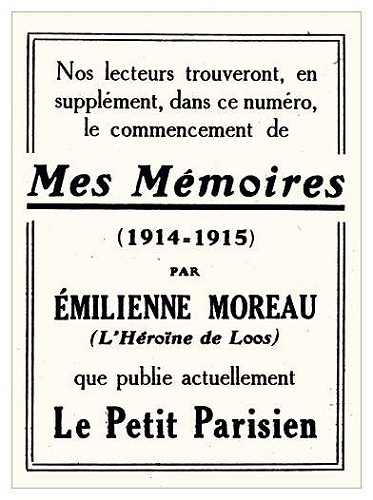

Advertisement in 'Le Miroir' issue no. 107 of 12 December 1915

from a British newsmagazine : 'the Illustrated War News'

In November, Miss Moreau was offered the royal sum of 5000 FF by the newsmagazine 'Le Petit Parisien' for the rights to publish the memoires of her war years and exploits during the battle of Loos. As she was very poor at the time, living on a war-relief allocation for the whole family of 5 FF a week, she accepted and her story was published in several news magazines (see advertisement and photos reproduced above).

She married in 1931 and went to live in nearby Lens. During World War II, her Great War exploits were not forgotten nor forgiven by the (second) German Occupation Authorities. A price was placed on her head. With her two brothers and husband she joined the underground Resistance movement and was active in both the north and south of France. Her war-time work took her to London and on parachute drops. After the Second World War she was decorated with the title 'Compagnon de la Résistance', a distinctive honor bestowed upon but 1000 other underground combattants.

From 1945 to 1963 she was active in the French Socialist Party and enjoyed an honored and respected career on various government committees, commissions and Ministry of Education posts. Emilienne Moreau died on January 7th 1971.