|

|

EVERY minute of the twenty-four hours the locomotives of the four British railways travel an average of nearly a thousand miles, equivalent to more than two journeys round the globs every hour. In one year the steam mileage alone amounts to over five and a quarter times the distance between the earth and the sun. There, in a few words, is an indication of the work done by the British railways. The term "railway" is quite inadequate to describe the ramifications of the system. For three-halfpence or a penny a mile the traveller is entitled to the use of a great transport undertaking that provides an unrivalled degree of comfort, speed, frequency and regularity of service. Included in the systems are one of the largest mercantile fleets in the world, the largest dock and harbour undertaking having single ownership, a thousand miles of canals, and a chain of hotels. In addition to these activities, the British railways own and operate the biggest cartage business in the world, control, or are otherwise interested in, about 15,000 passenger motor vehicles, provide all over the country warehouse and storage accommodation for the merchandise of their customers, and operate air services for the conveyance of passengers and goods. A British railway may, therefore, well be regarded as an immense department store, or universal provider, of transport. It thus differs from the railways of most other countries, which for the greater part do not own hotels, steamships or docks—the Canadian Pacific Railway, with its fleet of ocean and lake steamers and its luxury hotels, is an exception. Moreover, much of the cartage work undertaken by the railway companies of Great Britain would be transacted abroad by independent carriers. For instance, in the United States the handling of a large amount of parcels traffic and other small consignments of merchandise, which constitutes so much of the goods business on British railways, is not undertaken by the railways themselves, but by "express companies," who provide their own rolling-stock, in the same way as is done in England by the Pullman Car Company.

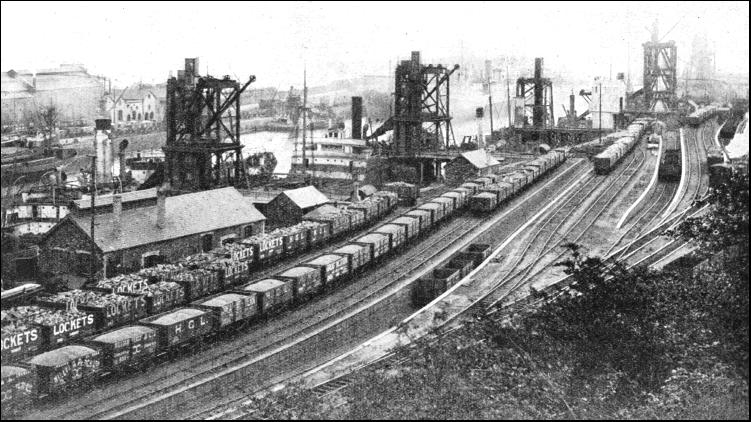

The British railways—and here again their practice is exceptional—are also manufacturers. They construct at their own works the bulk of their locomotives, carriages and wagons. Also permanent way switches and crossings, signal material, and many other requisites are made at such works as Crewe and Swindon, which in their turn have been the nucleus of large towns. This business of manufacturing rolling-stock and equipment (to which has lately been added the conversion of steam passenger stock for electrical working) represents a considerable business in itself, as does also the repair and renewal work carried out at the various "shops." To this day, as in the beginning, by far the largest single item of traffic carried by the British railways is coal. The exact beginnings of the railway are difficult, if not impossible, to trace, but in this country they were certainly connected with coal. According to some historians, a primitive form of railed track may have been in use in the Scandinavian countries as early as the sixteenth, or even the fifteenth, century. Be that as it may, we know that a line with wooden rails was built at Newcastle about 1602 for the haulage of coal from a local mine to a convenient point of shipment on the River Tyne. This little colliery line was the ancestor both of the British railway in particular and of railways in general. Well before the opening in 1825 of the Stockton and Darlington (the first public railway in the world) a relatively considerable railway mileage had already been built in England and Scotland With the exception of the Surrey Iron Railway, these lines were built solely for the conveyance of coal, and carried no other traffic. The Stockton and Darlington line was originally planned for "the more easy and expeditious carriage of coals, lead, etc." The conveyance of passengers, who travelled at first in horse-drawn cars, was an afterthought. Coal is still the backbone of the British railway business Of the railway receipts proper, apart from those of the steamships, docks, and other subsidiary businesses, over half are earned by the goods department. This figure would be still higher if it were not for the fact that the Southern is pre-eminently a passenger-carrying railway and derives only a quarter of its receipts from merchandise and minerals. In 1934 British railways carried nearly 168 million tons of coal, coke, and patent fuel, or well over half a million tons every working day. This traffic, which is exclusive of the fourteen or fifteen million tons of coal a year that the railways themselves require for locomotive and other purposes, represents about two-thirds of the total goods and mineral tonnage of all descriptions carried in 1934. Owing both to the great density of traffic, and to the fact that merchandise is normally carried in small consignments, which in turn means relatively small wagons and short trains, the proportion of locomotives to mileage in Great Britain is exceptionally high. In round figures, the four main railways own 19,300 miles of route, and 50,700 miles of track, including sidings and those sections of line on which two or more running roads are provided. This proportion of track to route mileage—rather over two and a half miles of track to every mile of route—is higher than in any other country, since a large proportion of the railway systems abroad is composed of single track. Excluding Diesel engines and cars, steam and electric rail motors, and other forms of traction, the work of the British railways is done by approximately 20,500 steam locomotives, of which rather less than two-fifths are tank engines, the latter representing an unusually high proportion. The locomotive is, of course, the keystone of the railway structure. One of the great preoccupations of engineers and managers is naturally to obtain the utmost amount of useful work from each machine. Locomotives are designed with an eye to fuel economy, since a variation of a shilling a ton in the price of coal means a saving or an extra expenditure of about three-quarters of a million pounds a year on the British railway coal bill. Moreover, there is a constant increase in size and power, accompanied in recent years by a decrease in the numbers of locomotives employed. Until a few years ago there was an invariable tendency for the number of locomotives to show an increase every twelve months, but this tendency has now been reversed.

In the long run these decreases become remarkable. Thus, while the London, Midland and Scottish Railway had 9,800 locomotives in service at the end of 1929, the figure had dropped to 8,004 by December, 1934. In other words, eight locomotives are now doing the work that six years earlier required ten. This result has largely been made possible by a considerable reduction in the average time during which locomotives are under or awaiting repairs. This means a reduction in the number of engines in the "shops" at a particular time, and a consequent increase in the work obtained from each engine. The reduction is also due to the rapidly increasing tractive power and efficiency of the standard types now being built. In addition to locomotives, the working stock of the main British railway system includes, in round figures, 61,000 passenger carriages and other coaching vehicles, together with electric stock, and a total of 619,000 goods and mineral wagons and departmental vehicles. The latter figure includes coal wagons for the use of the locomotive department, ballast wagons and brake vans, timber, rail and sleeper trucks, breakdown and travelling cranes, gasholder trucks, mess and tool vans, and other miscellaneous stock. This gives approximately one locomotive to every thirty-three vehicles of all descriptions. Even this figure fails to do justice to the work performed by the locomotive department, since, in addition to wagons in the ownership of the railway companies, there are considerably over half a million privately owned goods vehicles, most of which are exclusively used for the conveyance of coal. The tendency for the number to decline is not confined to locomotives. During 1929-1934 the number of coaching vehicles in use on the London, Midland and Scottish Railway fell from 26,809 to 24,023, and that of merchandise and mineral vehicles from 297,963 to 270,441, while the service vehicles were reduced from 20,156 to 15,584. Here, also, a large increase in capacity has gone hand-in-hand with the diminution in numbers. Every year shows a reduction in the wagon stock with a load capacity of less than twelve tons, and an increase in those built to take a bigger load. Another reason for the decrease both of rolling-stock and of locomotives is the speeding up of repair work. At the end of 1923 there was under and awaiting repair on the London, Midland and Scottish Railway a total of 1,958 locomotives, 3,062 coaching vehicles, and 14,006 merchandise and mineral vehicles. In every succeeding year there has been a drop, and the 1934 figures were 512 locomotives, 1,214 coaching vehicles, and 8,394 merchandise and mineral wagons. These figures indicate an even more striking speeding up than is to be seen on the surface. As many as 6,594 of the locomotives underwent renewals or light or heavy repairs during 1934, while the figures for coaching stock and goods and mineral vehicles were 12,219 and 498,972 respectively. In other words, most of the locomotives and over half the coaching vehicles went through the "shops" during the year, while every wagon was dealt with nearly twice, yet the waiting list represented so very small a proportion of the total. Expeditious work of this nature so shortens the time during which locomotives and rolling-stock arc immobilized that more work is obtained from each unit.

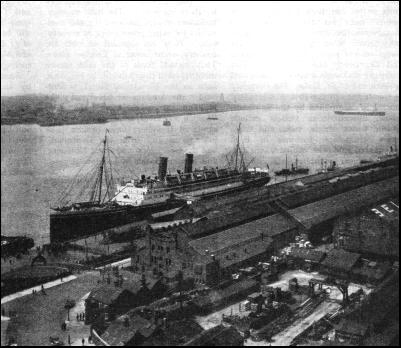

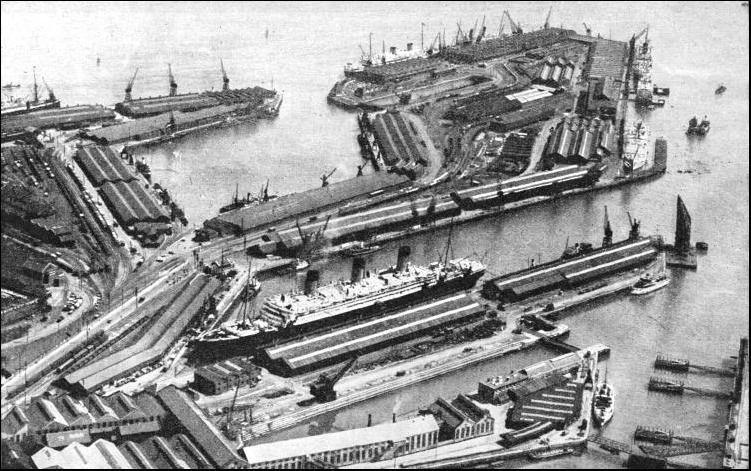

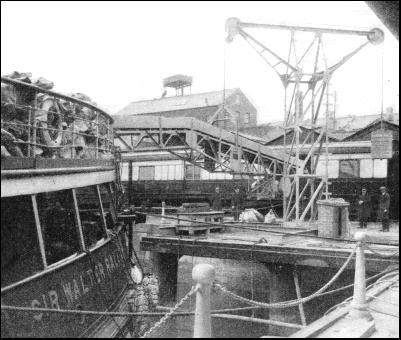

One word more before we leave the locomotive department. Each of the steam locomotives owned by the British main line companies runs an average of approximately 24,000 miles a year, nearly equal to a journey round the world at the equator. As with most figures relating to railway operation, this is also more striking in reality than appears on the surface. The average figure embraces every kind of work performed by every type of locomotive. A large proportion of the total amount of locomotive work, especially that in connexion with goods traffic, necessarily involves many stops and a low running speed. We thus have, on the one hand, the shunting engine, for which a hundred miles may represent a good day's work, and, on the other, the passenger locomotive performing such long non-stop runs as those of the "Flying Scotsman," the "Royal Scot," and the "Cornish Riviera Express." Many locomotives thus exceed the weekly average, which comes out at slightly over 450 miles. Next to the railway system proper, the largest business conducted by the British companies is that of dock owners. The railway-owned docks and harbours vary so greatly both in size and importance that average figures would be misleading. The magnitude of this particular business may, however, be gauged from the fact that the aggregate quay length amounts to considerably over half a million feet, or nearly a hundred miles. The largest and most important are Hull and Grimsby, owned by the London and North Eastern Railway. Grimsby is the premier fishing harbour in the United Kingdom. Other docks and harbours include Cardiff, Swansea, and Barry (Great Western Railway) ; Barrow-in-Furness and Grangemouth (London, Midland and Scottish Railway), and Southampton (Southern Railway). These range in size from the 16,092 feet of quay length at Grangemouth to the 64,063 feet at Hull, which is the largest of all the railway-owned docks. The London and North Eastern Railway Company is the largest individual dock owner in the world.

Southampton, with a total quay length of 30,068 feet and the largest dry dock in existence, is a striking example of a railway-owned harbour. To-day Southampton handles more ocean-going passenger traffic than any other port in the Kingdom, including London and Liverpool. Its position is a tribute to the enterprise of the London and South Western, which bought the docks in 1892, and of its successor, the Southern Railway. In a single month, as many as 460 vessels, carrying over 31,000 passengers, have entered and left the port, and the traffic is constantly on the increase, for which the popularity of cruising holidays is partly responsible. The magnitude of the railway-owned dock and harbour business is not generally realized, yet this side of the undertaking alone is among the greatest commercial concerns in the Kingdom. There is nothing comparable with it in any other country. The British railways, in fact, give the community a service that is both complete and unique, and one that embraces all forms of transport. The tendency for the railway to link up with other means of communication continues to develop, as has been seen in recent years in connexion with both the highway and the air. Air transport is the latest business in which British railways have taken an active interest. Not only are these air services directly linked up with railway travel, but on special occasions, such as the Grand National, the companies also give their passengers the choice of either means of transport for the whole journey. From the ownership of docks and harbours to that of steamers is a logical step. Almost the whole of the cross-Channel passenger traffic between England and France, handled by vessels flying the British flag, is carried by railway-owned steamers. Railway steamers serve also northern and southern Ireland, Holland and Belgium, and various British islands. The cross-Channel services operated by the Southern Railway, either exclusively or in connexion with Continental companies or corporations, include Dover-Calais, Folkestone-Boulogne, Folkestone-Dunkirk, Newhaven-Dieppe, Southampton-Havre, Southampton-St. Malo, and Southampton-Caen. The Dover-Ostend service is run by the Belgian National Railways. In addition, Southern Railway steamers link up the mainland of England with the Isle of Wight and—in conjunction with the Great Western Railway—the Channel Islands. The Great Western joins South Wales and Southern Ireland by means of the Fishguard-Rosslare Harbour service.

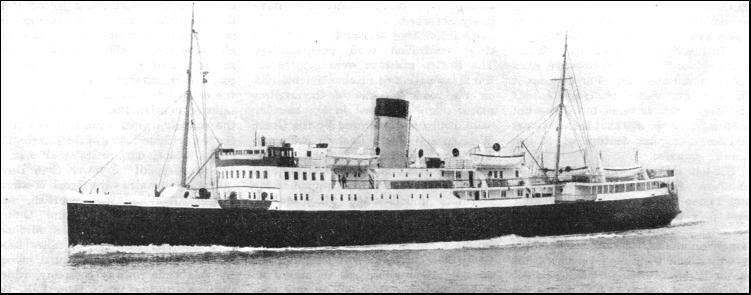

Three services are run by the L.N.E.R. from Harwich—to Hook of Holland, Antwerp, and (in summer only) to Zecbrugge, while Dutch and Danish companies run services from the same port to Flushing and Esbjerg respectively. L.N.E.R. steamers also ply regularly between Grimsby, Rotterdam and Hamburg; and in summer a joint L.M.S.-L.N.E.R. service is run between Hull and Zeebrugge. The L.M.S. operate or are interested in five sea routes between Great Britain and Ireland : Heysham-Belfast, Holyhead-Dun Laoghaire (Kingstown), Stranraer-Larne, Liverpool-Dublin, and Liverpool-Belfast. L.M.S. cargo steamers operate also between Goole and Amsterdam, Antwerp, Rotterdam, Ghent, Copenhagen, and Hamburg. These vessels take a limited number of passengers. On the Clyde the L.M.S. and L.N.E. Railways operate extensive steamer services to and from the many coast resorts, and those in Bute and Arran ; the L.M.S. services are run by a subsidiary company under L.M.S. control. L.M.S. steamers run on certain of the English lakes. The total railway-owned fleet, excluding vessels worked by the railway companies for other owners, and those on the Newhaven-Dieppe route, amounts to over 140 steamships. Many of these have been built for speed, their horse power being exceptionally large in relation to their size. The most powerful is the Southern Railway's "Brighton," of 16,400 h.p., after which come the four London, Midland and Scottish vessels working on the Anglo-Irish service—"Anglia," "Cambria," "Hibernia" and "Scotia"—which are each of 16,000 h.p. Then follow the Southern's "Worthing" (14,500 h.p.) and "Paris" (14,000 h.p.), while the London and North Eastern's Amsterdam, Prague and Vienna are of 13,000 h.p. These last, which have an unusually broad beam and spacious cabins, have aptly been described as ocean liners in miniature, and in common with their larger sisters, handle cruising as well as ordinary traffic.

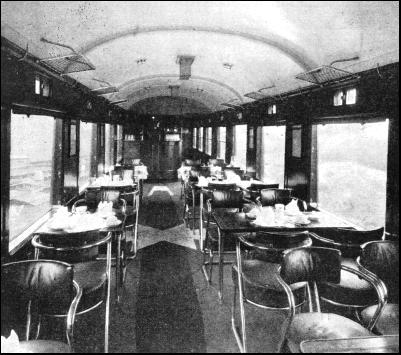

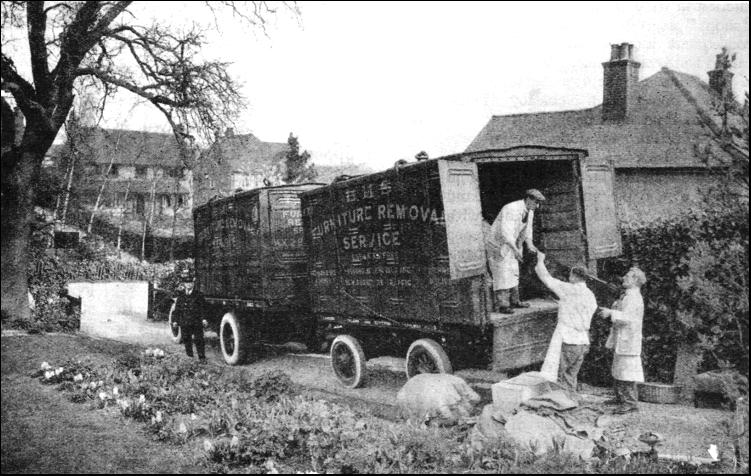

The British railway fleet varies considerably both in size and character. Thus, at the one end of the scale are the fast turbine vessels, and at the other a number of steamboats of under 250 tons. In between come such special craft as the Southern Railway's Auto-carrier, built for the conveyance of motor-cars, the same company's electrically-driven floating crane, and the cargo vessels plying between England and Cherbourg and Honfleur. This company also owns a motor launch that is stationed at St. Malo The diversity of this branch of the British mercantile marine is exemplified by the Southern, whose miscellaneous vessels include paddle boats, single, twin, and triple screw steamships, turbines of both the geared and the ordinary variety, coal barges, lighters and hulks, steam launches, tugs, tow boats and hopper vessels, and ash barges. The Southern Railway has also train-ferry interests, as has the London and North Eastern Railway. At one time it was the fashion to call the subsidiary railway businesses "side shows," but, save for such exceptions as the limestone quarry owned by the London, Midland and Scottish, each of these "side shows" is a considerable undertaking in itself. The hotels, for instance. Not many people, even those with a good knowledge of railways, realize that the four great British railway companies own the largest chain of hotels in the world The total number, including those managed by the companies for other proprietors, is seventy-nine They are situated all over the country, eight being in London alone. They include some of the best known institutions of their kind in the kingdom, such as the Gleneagles Hotel, in Scotland ; the Adelphi, at Liverpool ; the Midland, at Manchester ; the Lord Warden, at Dover, where so many thousands of travellers have broken their journey to and from the Continent ; and the Great Eastern, Great Northern, and Euston Hotels in London. Allied to the hotel business is that of restaurant cars and refreshment rooms. Excluding Pullman cars, which are not owned by the railway companies, there is a total of nearly seven hundred restaurant cars in service. This facility is equally available to the third- and the first-class passengers. Every train, including the fastest and most luxurious, is open to the third-class traveller. Moreover, where a supplementary charge is made, as on the "Brighton Belle," this is far more modest than the addition to the normal fare payable on American and Continental luxury trains. The same holds good of sleeping cars, as will be seen by comparing the charge of £1 for a "sleeper" between London and Aberdeen with that for a journey of corresponding length abroad. Another important business operated by the British railways is that of cartage. This has grown to its present dimensions because of certain operating conditions peculiar to Great Britain and Ireland. The majority of the merchandise consignments are small in bulk, weighing less than half a ton, largely because the speed of the goods services makes it unnecessary for a trader to hold large stocks of merchandise when the railway will so quickly bring a fresh supply to his warehouse or shop. As was declared over forty years ago by one of the most celebrated of all the writers on English railways, "celerity in goods traffic seems to have been a special feature of English railway management from the very first. . . Speaking broadly, it may be said that the whole English goods traffic is nowadays organized on this basis—that the railway receives the goods from the consigner the last thing at night, and hands them over to the consignee the first thing next morning. . . . The Bradford woollen manufacturer attends the London wool sales, buys Cape or Australian wool, and then goes home to bed. At 7.15 next morning his wool reaches Bradford, and after breakfast he can set his hands at work to unpack the bales. It might be thought that speed such as this was fast enough for anything ; but . . . the market traffic (fish and meat) goes much faster yet."

If all this was true in 1890, it is much truer to-day, when express goods trains composed of continuously braked stock traverse the country in all directions, running at almost express speed. With such a service there is a strong inducement for consignors to dispatch their traffic frequently and in small quantities. It often suits both the traders and the railway companies if the whole of the transport is in the same hands from door to door. Freight traffic is, therefore, expedited by the use of containers, of which there are over 10,000 in use. Containers enable goods to be conveyed from door to door without transhipment. The container is not a recent innovation. It was used for coal traffic on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway almost at its opening. It was adopted with a considerable measure of success on the Canterbury and Whitstable line. In the 'forties its use was suggested as a means of overcoming the inconvenience due to the break of gauge when transferring goods between the Great Western and Midland systems. For decades it has been employed on the cross-Channel and Anglo-Irish services, but it was not until a few years ago that the container became a regular feature of British railway practice. The four main railways own, in round numbers, 36,600 road goods vehicles and 14,200 horses, the latter including over four hundred used for shunting purposes. The railways still rely largely on animal traction, considerably less than half their road vehicles being motor driven, though about 1,600 "mechanical horses" were in use in 1934. Experience has shown that each type of vehicle has its advantages. The above figures are far from showing either the full scope or the real magnitude of the highway business carried on by the railway companies, since their accounts and statistical returns do not show the fleets of the passenger transport concerns in which they are interested, or of the large cartage undertakings that they have lately absorbed. An interesting history is attached to these controlled road undertakings. The British railways were pioneers in the introduction of mechanical traction on the roads. Some of the earliest motor omnibuses seen in the country were owned and operated by the Great Western and North Eastern Railways. The North Eastern introduced motor coaches over a quarter of a century ago. But the British railway companies are statutory undertakings, which means, among other things, that they are often not free to undertake a particular business unless specifically authorized by Parliament to do so. They did not consider themselves free to undertake mechanical road traction on any considerable scale until the passing of special legislation in 1928. Since then, instead of competing with existing road services, they have acquired an interest in most of the principal passenger-carrying undertakings operating outside the London area. In this way a great road and railway partnership has come into existence. The thousand miles of railway-owned canals largely represent a legacy from the early days, when the canal companies saw their traffic passing to the railways and their shares falling in value. The railways took over waterways as the price of overcoming the opposition of the canal interests to schemes for new railway construction. The length of the railway-owned canals ranges from the thirty-three chains of the Kensington Canal, which, despite its small size, is the property of no fewer than three railway companies—the Great Western, London, Midland and Scottish, and Southern—to the Shropshire Union, which belongs to the London, Midland and Scottish, and is 194 miles long. Another quite important canal owned by this same railway company, which possesses rather more than half the total mileage, is the Trent and Mersey Canal, which has a length of 117-1/4 miles.

Most people probably imagine that the land and property owned by the railway companies is restricted to tracks and sidings, stations, warehouses, shunting yards, workshops, locomotive and carriage sheds, and the like. But the item officially known as "land, property, etc., not forming part of the railway or stations," represents another considerable business, amounting to 35,000 acres of agricultural, urban and suburban land, and over 53,000 houses and cottages, of which 28,000 are occupied by the members of the staffs. With the exception of certain local authorities, such as the London County Council, the railway companies are the largest individual house owners in the country. This property ranges from small dwellings to large houses in residential districts, as, for instance, Hampstead. Much of it has been acquired to secure in advance land that may be needed for future track widening or station enlargements. This was done by the Great Central Railway when it built its London Extension. Hence the London and North Eastern Railway, in which the Great Central is absorbed, owns a number of houses in the immediate neighbourhood of Lord's Cricket Ground. To deal fully with the many and varied activities of the British railway system would require a large-sized book. There is never a lack of new developments to record, such as railroad depots, at which traders' merchandise is stored until needed ; the provision of special warehouses for individual large customers ; and the use of containers, to which reference has already been made earlier on this page. It has been said by a great authority that British railways "now sell service, whereas they used only to run trains." Here we have in the fewest words a definition of the new spirit of enterprise that has characterized the administration and management since grouping in 1923. This wholesale amalgamation brought in its wake many new problems, since twenty-seven large and ninety-three small concerns were obliged at short notice to fuse into only four undertakings. The enormous difference that the railway companies have made in the social life of Britain cannot be exaggerated. The sites of our homes are dictated in some measure by the railways. Particularly is this so in the London area, where the provision of a fast and frequent electric train service has made it possible for the City worker to live ten, twenty, or thirty miles out of town in rural surroundings. Reasonable season-ticket rates have also contributed in no small measure to the movement of a concentrated population in, and adjoining, our large cities to the open country and to the sea coast. A comparison between life in a country district and that in the smoke-laden atmosphere of a large town requires no emphasis, and the energy and enterprise of Britain's railways have contributed to improved conditions for hundreds of thousands of her people. A sidelight on this phase of the railways' activity is furnished by the camping and holiday cruising arrangements now made for the public. Full descriptions of both these delightful ways of spending a holiday have appeared on other pages. There are other angles, however, from which the railway industry of Britain may be viewed. For example, the financial importance of British railways can be gauged from the tact that the capital receipts for the four main British groups, namely the Great Western, the London and North Eastern, the London, Midland and Scottish, and the Southern Railway, to the end of 1934 amounted to no less than £1,092,000,000, while the capital expenditure was £1,154,000,000. It would seem from these figures as though the expenditure exceeded the receipts, but the difference is met, temporarily, by various renewal, superannuation, and savings bank funds. About ten per cent of the total expenditure relates to docks, steamships, hotels, and other subsidiary businesses conducted by the companies. One aspect of the railways' national importance is apt to be overlooked, and that is that the various companies are the country's best customers, since their purchases reach colossal proportions. For example, the companies between them purchase no fewer than 14,000,000 tons of coal every year to supply the needs of some 20,000 locomotives and for steamships, hotels, offices, and works. British brick-makers supply the railways alone with some 14,000,000 bricks, textile mills sell 2,600,000 yards of cloth to the railways each year, and steel works supply railways to the extent of 195,000 tons. In giving their multitudinous services the railways also find employment for a vast number of men and women.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |