|

|

AMONG the great international express trains of the International Sleeping Car Company none is perhaps more fascinating than the "Taurus Express," with its connecting services to Baghdad and Cairo. Its route is from Haydarpasa, on the Bosporus opposite Istanbul, across Asia Minor to Aleppo and beyond. The history of the railways in Asia Minor is one of the most interesting chapters in the annals of railway construction. The first project for a railway dates back to 1836 and was formulated in Great Britain by Colonel Chesney. Even in those days that country had considerable interests in Asia and was interested in keeping open the overland route to India. Great Britain already dominated the seas, but steam navigation was still in its infancy and not yet sufficiently safe for long voyages. In this project of 1836 appears the first suggestion of a railway in the direction of India. The idea of steam navigation was abandoned in favour of a railway, which was planned to run from the Mediterranean via Baghdad to the Persian Gulf. It is curious that the Baghdad Railway scheme should stand first in the history of the Turkish Railways. But the development of steam navigation revived the interest of the British Government in the sea route to India, and Colonel Chesney's project was pigeon-holed. A regular steamship service took the British mails from England to Alexandria. From Alexandria they were carried overland to Suez, and thence by sea to India. In 1850 Colonel Chesney appealed to private enterprise tor the necessary capital, and his project attracted considerable interest in many quarters. But nothing ever came of it, as the Crimean War of 1854-6 was soon to convulse Europe.

At the end of the war a period of feverish activity began in the Ottoman Empire, and the first railway concession was granted in 1856 to a British company, called "The Ottoman Railway from Smyrna to Aidin." The old project of the Baghdad Railway was revived, but it was checked by the completion of the Cairo-Suez Railway, which improved communications with India. Once more this great scheme remained in abeyance, and it was not till 1871 that the first step was taken for its realization. In that year the construction ot railways in Asiatic Turkey was put in hand by the Ottoman Government. The line from Haydarpasa to Baghdad was to be the first railway in the Asiatic Dominion of the Turkish Empire. After a hasty survey, work was begun in August 1871, and exactly two years later the first section to Ismid, a distance of twenty-nine miles, was completed. Once more the Baghdad Railway project was brought forward. In 1872 the British Government appointed a special Commission under the chairmanship ot Sir Stafford Northcote to investigate the whole question. The report of the Commission was submitted to Parliament on July 27, 1872. It recommended that, besides the Suez Canal, a second line ot communication would be ot great and increasing value, and that the Government should leave nothing undone to ensure this end. Notwithstanding this strong recommendation, the Government of the day did not come to any practical conclusion, and even refused to guarantee the interest on the capital Two years later Disraeli effected the purchase ot the Suez Canal shares, and, a dreaded competitor being thus eliminated, Great Britain lost for the time being all further interest in the Baghdad Railway. Turkey now began to take interest in the idea. In a report submitted to the Sultan in 1880 by the Minister of Public Works, the Baghdad Railway took first place among the various public undertakings under consideration. The project had no better fate than the others, including those which had agitated public opinion between 1878 and 1886. Among them was that promoted by a syndicate under the chairmanship of the Duke of Sutherland, who sent an expedition headed by the great explorer Cameron to map out the line. With the widening ot the Suez Canal in 1886, Great Britain was confirmed in her withdrawal from the field. Although France had great political and commercial interests in Turkey, she confined her railway activities to lines of a more local character. In 1888 a new competitor suddenly appeared. This was Germany, whose influence at the Court of the Sultan grew with the weakening of British and French influence. In October, 1888, Europe was startled by the news that the Sultan had granted a concession to Germany for the construction of the railway from Ismid to Ankara via Eski Shehir. The second step in the construction of the Baghdad Railway was thus ensured. A new era in railway politics now began for Turkey. During the next five years concessions were granted for railways in Asia Minor totalling 2,995 miles, the great majority to French and German capitalists. Great Britain remained outside. The vast capital invested by France in Turkey—it amounted in 1914 to £80 million gold, of which £20 million were in railways—almost gave that country a controlling interest. Germany, mainly through the far-sighted policy of the Deutsche Bank, assured herself a steadily growing influence at Constantinople (now Istanbul).

In 1889 the Société Ottomans des Chemins d,f Fer d'Anatolie (Ottoman Company of Anatolian Railways) was founded. This German company took over from the State the old line from Haydarpasa to Ismid. The old line was in such a deplorable condition that a new track had to be built by a company of contractors, formed for the purpose, and composed ot the Régie Générale des Chemins de Fer (General Railway Administration) of Paris and the firm of contractors, Philipp Holzmann of Frankfurt. Work was begun in May, 1889. In December 1892 the line to Ankara, a distance of 305 miles, was completed. In 1893 the Anatolian Railway obtained the concession for the line from Eski Shehir to Konia—the third stage of the Baghdad Railway. This line was built by a number of contractors, again headed by Philipp Hoizmann. The contractors completed the line of 276-1/2 miles by July, 1895. Two years later the Turkish Government began negotiations with the Anatolian Railway for the construction of the Baghdad Railway. Whereas previous projects had favoured a line from Ankara via Sivas, the extension of the line from Konia now found considerable favour. A number of new parties appeared on the scene with fresh schemes. Among these parties was a British group, of whom an interesting story is told. It is said that, in the hope of obtaining the Sultans personal intervention in their favour, the aspirants presented Abdul Hamid with a map worked in pure silver on which the projected railway line was set out in costly gems. About this time also Russia submitted plans for railways to link up with the Russian railways ; two main lines to Baghdad and Basra on the Persian Gulf were to be connected via Tabriz, in Persia, with the Trans-Caucasian Railways. But all these projects were either financially unsound or politically suspect. The German Emperor now made his spectacular and fruitful visit to Constantinople. Various new railway concessions and the construction of the harbour works at Havdarpasa were the immediate result. Moreover, the imperial visit was not without influence on the negotiations about the Baghdad Railway then proceeding. At the instance of the Government the Anatolian Railway Company dispatched a Commission of German engineers and experts to investigate the proposed route of the Baghdad Railway. During their absence the activities of the chairman of the Deutsche Bank, Dr. von Siemens, brought matters to a head. The provisional agreement, signed on November 27, 1899, was a bombshell in the European chancelleries. Many obstacles were still to be overcome and years passed until the opposition raised by Russia and England was overcome. Russia, who had cleverly managed to prevent the construction from Ankara via Sivas, was opposed also to the new southern line from Konia. Great Britain's attitude, which so far had remained that of an aloof spectator, sceptical as to the final outcome, was distinctly hostile now that the Baghdad Railway had entered upon the stage of realization. France having invested so much capital in the country, could not remain indifferent.

An understanding between the Deutsche Bank and the French capitalists was, however, arrived at, by which the capital of the new company to be formed was to be divided between the two countries in equal shares and with equal rights. A new technical Commission was sent during the winter of 1899-1900 to establish the definitive route of the railway. At the same time the German cruiser "Arkona" surveyed the Persian Gulf to determine the most suitable locality for a terminus of the railway. The report of the Commission declared that the construction of the line from Konia would be feasible but difficult, and suggested several alterations in the route. Thus the passage from Asia Minor to Northern Syria was to be moved from the Alexandretta-Berlau Pass to the more northern route via Osmanie. This alteration was made in deference to the representations of the Turkish Government, which did not favour the construction of the line along the coast where it might be exposed to enemy fleets. Another important alteration was that which moved the line via Nisibin, and the transfer of the line from Mosul to Baghdad from the eastern to the western bank of the Euphrates. The contract was signed in 1902 after all the financial arrangements had been made. The Turkish Government undertook to pay a sum of 15,500 francs (£620) per kilometre (five-eighths of a mile), which was guaranteed by State monopoly on various articles and an increase of customs duties. But here the other European Powers, signatories of the Dette Ottomans (the Turkish Public Debts Control Board), intervened, and it seemed as if an agreement would be difficult to reach. The conflicting political interests of the various European countries hampered the construction of the overland route to the East, and once more the Chancelleries of Europe were busy, once more Asia Minor, as thousands of years before, dominated the attention of the world. To make a start with the construction of the railway, it was decided to divide the whole line into independent sections of 125 miles, the completion of which and the guarantee funds for which would be independent of one another. In this way it was possible for the Government to find the guarantee funds out of other sources without encroaching upon the Dette Ottomans conditions. On March 5, 1903, the appropriate decree was signed by the Sultan, Abdul Hamid, and the great work was now to begin. Nearly seventy years had elapsed since the first idea of a Baghdad Railway had been conceived by Colonel Chesney. Two clauses in the agreement are of particular interest, as they show the respect Abdul Hamid had for Britain. Paragraph 8 of the concession stipulated that the railway must never pass into other hands, while Paragraph 29 provided that the line between Baghdad and the Persian Gulf was not to be opened for traffic until the line from Constantinople to Baghdad had been completed.

In April, 1903, the Societt Impérials Ottomans du Chemin de Fer de Bagdad (Imperial Ottoman Company of the Baghdad Railway) was constituted in Constantinople. In view of the international character of the railway the company endeavoured to interest British capital. London financial circles, as well as the British Government, were favourably inclined towards a financial participation, when suddenly a violent press campaign was launched against the venture. The result was that both Government and the London market withdrew. Thus it came about that Great Britain still remained outside. The construction of the first section, from Konia via Eregli to Bulgurlu, was begun in July, 1903, by a syndicate formed lor the purpose, in which the Philipp Hoizmann Company of Frankfurt again took the leading part. Eighteen months later this section of 125 miles was completed. It was, for administrative purposes, provisionally transferred to the Anatolian Railway Company.

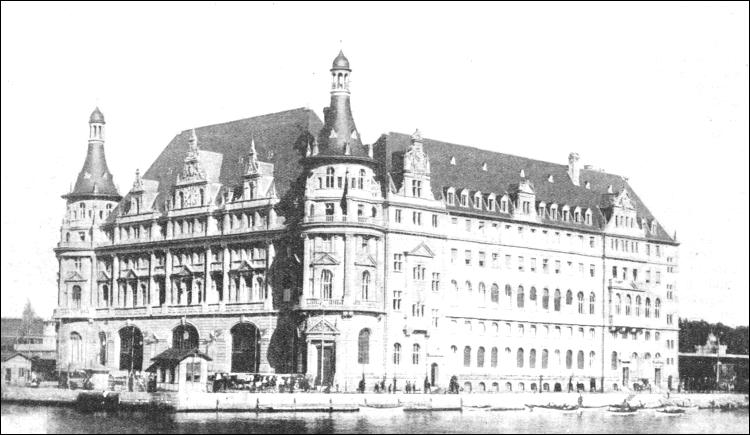

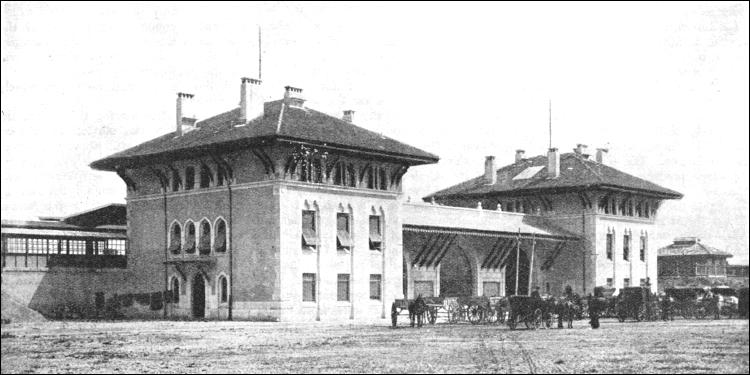

The inability of the Turkish Government to find the necessary guarantee funds delayed the construction of other sections, and years had to pass until all these difficulties were overcome. It was not till 1908, after the unification of the Turkish Debt, that sufficient funds became available for the conclusion of an additional agreement for the extension of the line to Helif (522 miles). After many vicissitudes a conference was held in 1910 at Potsdam (Berlin), at which the principal European powers were represented. This led to a further additional international agreement whereby the Baghdad Railway Company obtained a concession for continuing the line from Helif to Baghdad. But the railway company relinquished its right to the construction of the railway from Baghdad to Basra, on the Persian Gulf. This was transferred to a Turkish company constituted for the purpose. Germany further undertook not to build any port or railway station on the Persian Gulf without British consent. By this move the company came to an understanding with Great Britain. During the period from 1912 to the outbreak of the war of 1914-18 an aggregate of 330 miles in different parts of the country was opened for traffic. During the war the German Government advanced the necessary capital to the Turkish Government, as the completion of the line was a matter of vital importance to the German and Turkish armies. To speed up construction, it was decided to build the remaining sections to the narrow gauge of 60 cm. (2 ft.), and to leave to a later period its alteration to standard gauge. By the beginning of 1917 the mountain ranges of the Taurus and the Caucasus had been pierced and through communication established. The alteration of the Taurus line to standard gauge was completed in October 1918—a few weeks before the Armistice, and not, therefore, of much benefit to the German and Turkish armies. After the Armistice the line passed temporarily under British control and work was continued. During the war the British troops had built a strategic line of metre (3 ft. 3-3/8 in.) gauge from the Persian Gulf towards Baghdad, which is still in use. Up to a few years ago, that is, before the International Sleeping Car Company had inaugurated the service of the "Taurus Express" in connexion with the "Simplon Express," the journey across Asia Minor was somewhat of an ordeal. To-day, however, it is rendered as pleasant as anywhere in Europe. Such pleasure is greatly enhanced by the fascination which a trip by the "Taurus Express" exercises, even on the most jaded mind. It is difficult indeed to conceive a journey through any other land which leaves such a deep impression on the mind. On the "Taurus Express" the passenger falls a victim to the spell of a great past. Here is a bygone culture, buried beneath the sands of the desert, here and there are brought to light traces of mighty cities and of mightier kingdoms. Haydarpasa, on the Asiatic side of the Bosporus, the starting-point of the journey, lies opposite Istanbul, once Constantinople. Istanbul, extending along the Golden Horn, with its thousands of minarets glittering in the sun, is one of the most beautiful cities in the world. Haydarpasa, the former terminus of the Anatolian Railways, is a large structure built in a rather florid style, a blend of Western and Oriental architecture. Under the efficient administration of the Turkish State Railways the station has been modernized and presents an up-to-date aspect, with all the appurtenances of a busy railway centre.

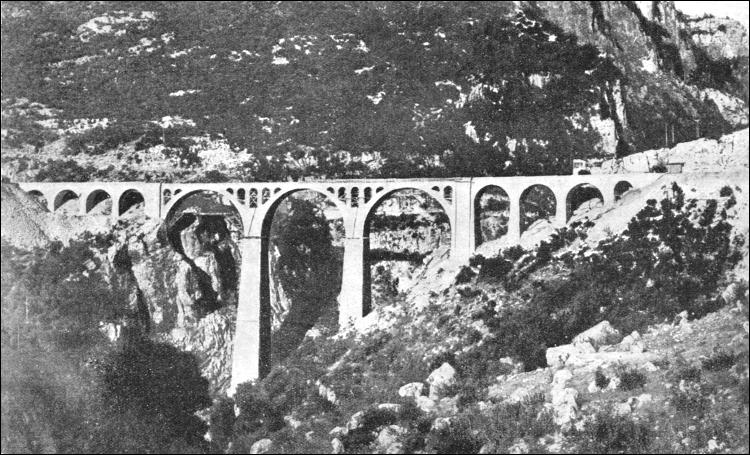

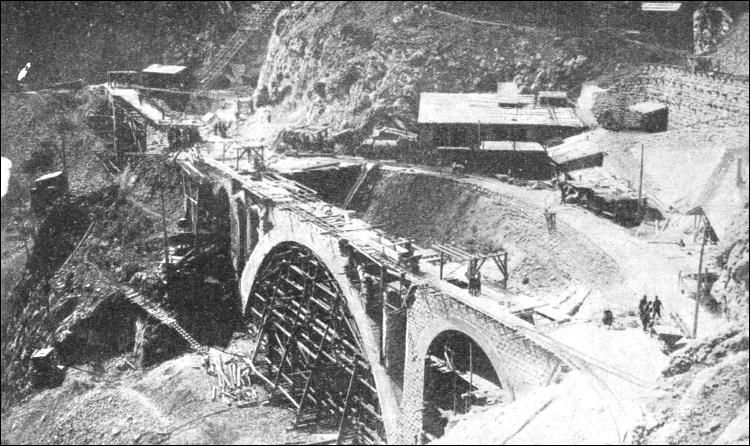

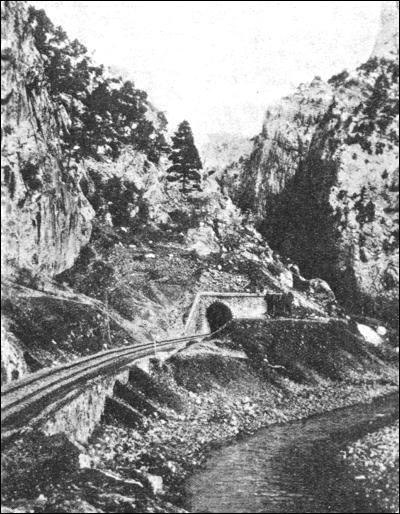

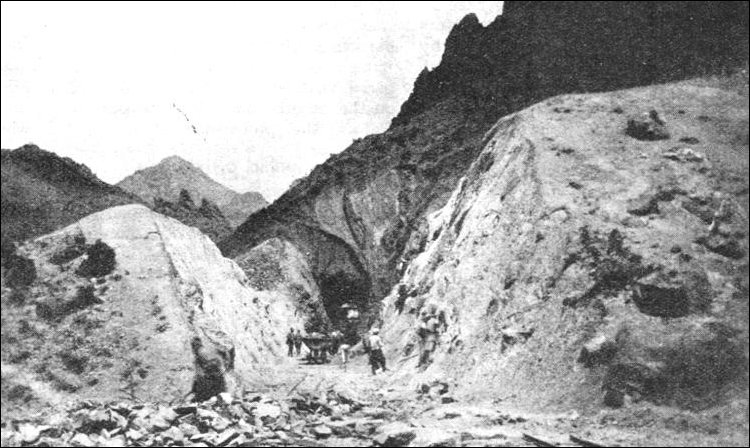

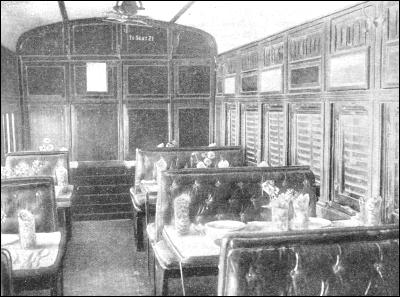

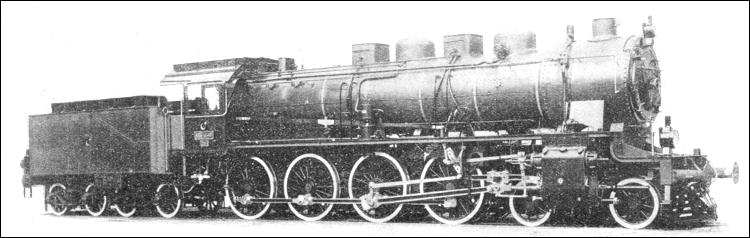

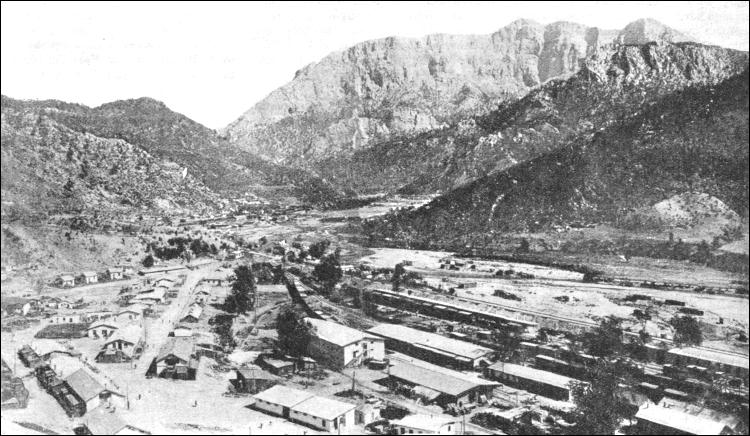

A powerful locomotive, built by one of the great German works, is ready to haul the train, which is composed of two sleepers, a dining-car, and a luggage van. There are also first, second and third-class ordinary coaches between Haydarpasa and Adana. The station and train staff have a smart appearance. The staff of the dining-car is busy taking in large blocks of ice, and fruit is delivered in large baskets. The train leaves at 9.40 a.m. Soon after steaming out of the station we travel among beautiful suburbs, with princely villas among flowering gardens on the coast of the Sea of Marmora and along the Gulf of Ismid. The gulf affords a beautiful view, with Istanbul in the background. After the station ot Ismid the line runs through swampy land on the banks of the Lake Sabaudja, and enters the fertile valley of Sakaria, where tobacco and chillies are cultivated by Muhadjers (Turkish peasants), who were settled here by the Turkish Government. They are mostly immigrants from districts which are now under foreign rule. The line then enters the valley of the Karasu, an affluent of the Sakaria, and rises 950 feet in a distance of seven and a half miles. Bridges, tunnels, and cuttings alternate in almost continuous sequence. The great Anatolian plateau lies in front of us—a vast expanse, intensively cultivated in parts, almost desert in others, where water is extremely scarce. The train reaches the important junction of Eski Shehir, and since 1935 has run thence via Ankara, the capital of Turkey. Eski Shehir is famous for its mosques, which date from the ninth and tenth centuries, and for its hot springs. The former route was via Afyon—the Achrones of antiquity—which is noted for its citadel 370 ft. high, built upon a conical hill. Next came the station of Konia (the ancient Ikonium), where remarkable early monuments are found and some fine mosques. Konia, or Kenya, is a large town, and lies in the centre of a fertile district. Considerable irrigation works were carried out here by the late Anatolian Railway Company, the water being derived from Lake Bey Sekehir Go and conveyed through canals 170 miles long. Konia was the terminus of the old Anatolian Railway, and here begins the Baghdad Railway proper. The first section of the line from Konia to Bulgurlu (127 miles) is laid over flat country, and no engineering works of any importance arc encountered. The plateau lies at an average height of 3,300 ft. The next section from Bulgurlu to Yenice is one of the finest pieces of railway engineering on the line. The line here traverses the Taurus Mountain range in a south-easterly direction towards the coast, and reaches, three miles north of the station of Ouloukichlar, its maximum height at 4,845 ft. above sea-level. The original idea was to pierce the mountain range by one long tunnel, but the necessity of completing the line during the war induced the Government to construct a series of tunnels instead, as this allowed of simultaneous work in several places. The series of tunnels begins at a point 225 miles from Konia. and continues for eight miles as far as the station of Hadjikiri. There are in all twelve tunnels varying in length from 40 to 2,300 yards. Their total length is 7 miles 580 yards, and there are only 1,863 yards of open track between the tunnels, including 362 yards of bridging. The longest bridge is a concrete structure composed of one span of 165 ft., one of 33 ft., and one of 16-1/2 ft. The banks of the rivers are steep, and consist of limestone rock. In many places they are close to one another, forming gorges a thousand feet deep into which the sun never penetrates. The spectacle is often almost terrifying in its weird and sombre grandeur. The construction of the tunnels was a difficult undertaking. For the surveying alone fourteen miles of road had to be constructed, on which several thousand men were employed during a whole year. This in itself was an engineering feat, as the roads were built on top of the mountains and zigzaged down to the gorges To facilitate access to the mouths of the tunnels the concrete bridges over the gorges were built first. This series of tunnels follows the course of the Chakit Torrent, which runs between precipitous high mountains and descends in several cascades from a height of 1,600 ft. between the two end tunnels. The mountains are of a hard limestone rock and, with the exception ot a few pockets of clay which caused some inconvenience, the boring proceeded without incident. The tunnels are lined only in those sections which required strengthening because of the nature of the rock. Ordinary masonry lining was used, with a concrete crown. In the majority of places the tunnel is not lined, as the hard rock is extremely compact. Shortly after leaving this region the train reaches the station of Yenice, which lies 104 ft. above sea-level. We have been travelling over twenty-five hours since we left Haydarpasa. Yenice is the junction for the railway line to Mersina. Our next stop is Adana, a busy and important commercial centre on the banks of the River Sheihun, which we cross on a steel girder bridge 1,040 ft. long. The bridge is composed of four spans of 177 ft. and one of 315 ft. The masonry piers rest on oak piles.

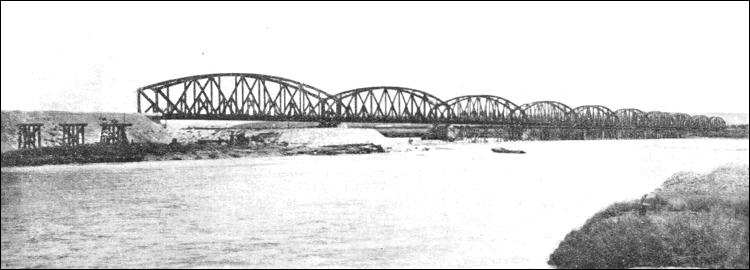

At Adana the Turkish State Railways come to an end. We enter Syria, and the line now belongs to a French company as far as Aleppo. Shortly beyond Adana, the River Tihun is crossed by a bridge composed of four steel girders, each of 164 ft. span. The line rises now again beyond the station ot Mamourié, and negotiates the Amanus Mountain range by a series of fourteen tunnels. The construction of this part of the line was fraught with considerable difficulties because of the inaccessibility of the mountains. Between the stations of Mamourié and Islahie, a distance of twenty-one miles, nearly six miles of tunnels had to be constructed, the longest of which is the Bagtschi Tunnel, with a length of 5,365 yards. This tunnel was bored through hard rock which was sufficiently compact over the second halt to render lining unnecessary. It is located at an average height of 2,500 ft. above sea-level. We rapidly descend and, near Radjoun, cross a deep gorge by the Here Dere Viaduct, a steel girder construction consisting of three spans each of 243 ft., one span of 131 ft., and one of 46 ft. The girders rest on towers of steel trestle work 280 ft. high. We next travel in a south-easterly direction to Aleppo, which is reached shortly after 10 p.m. Aleppo is an important commercial town, the history of which dates back to the earliest times. It is famous for its "Souks," as the bazaars are called here. From Aleppo a railway line branches off to Tripoli on the Mediterranean, whence a motor-coach belonging to the International Sleeping Car Company conveys passengers over well-kept roads to Beirut and Haifa in eleven hours. From Haifa a through train, with dining cars, leaves on the following morning at 8.30, arriving at Cairo the same evening at 10.30 p.m. The " Taurus Express " leaves Aleppo at 10.40 p.m. and runs through the fertile plains ot Syria. Near Jerablus the River Euphrates is crossed by a bridge consisting of ten steel girder spans of 263 ft. each. This bridge is a fine construction resting on masonry piers built on oak piles, which were driven by means of special steel sheet cofferdams to a depth of over 30 ft. below the river bed.

Soon after crossing the Euphrates the line rises slowly to an altitude of 2,670 ft. above sea-level. At 11 a.m. we arrive at Tel Kotchek, the last station on the line. Motor-coaches belonging to the International Sleeping Car Company are waiting at the station to convey passengers by road to Mosul and Kirkuk. Near Tel Kotchek the frontier between Turkey and Iraq has been crossed. We now travel over ground which, from its Biblical and historical associations, may justly be called the cradle of civilization. Mosul lies on the bank of the River Tigris, and is a handsome town built of the strikingly white stone found in the district. In its immediate neighbourhood two mounds mark the site of one of the greatest cities of bygone ages—Nineveh, the capital of the kings of Assyria. Nothing remains above ground to testify to its past greatness. But the incomparable collection of Assyrian treasures in the British Museum which Sir Henry Layard discovered during the excavations made by him in 1845 reveal the high degree of civilisation which the Assyrians had reached. Among other treasures 22,000 tablets were discovered from the library of the great king Ashurbanipal, some of them recording the story of the Great Flood. The run from Tel Kotchek to Mosul lasts two and a half hours; passengers remain overnight at Mosul and proceed the next morning in the same motor-coach to Kirkuk, which is reached at 5 p.m. Here begins the Iraq Government railway line, which brings us in a comfortable sleeping car of the International Sleeping Car Company to Baghdad, the journey occupying twelve hours. Baghdad was formerly called Medinat as Salam ("The City of Peace"). To-day it is described as "the city of amazing contrasts between early medievalism and the last word in modernity, an apparently hopeless jumble of the tenth and the twentieth centuries. "Baghdad was the city of the Arabian Nights, of Harun ar Rashid, and was once the centre of a religious world, of fabulous luxury and magnificence. It was destroyed and its inhabitants were put to the sword by Hulagu Khan, at the head of his endless hordes of Mongols. The city was hardly on the way to recovery when it was sacked again by the Mongol King Tamerlane, notorious for his pyramid built of thousands of heads that fell under the unerring axe of his executioners.

The train has arrived at Baghdad at 8 a.m. The new station is a comfortable, well-planned building which houses the administration of the Iraq Government Railways. As stated earlier on this page, the railway line on which we are now to travel was originally laid by the British Army during the war of 1914-18, to connect Basra with Baghdad. The "Taurus Express"—now the "Iraq Express"—leaves Baghdad punctually at 6 p.m. Fresh supplies have been taken in, including large quantities of ice for cooling the cars. We are entering upon the last stage of our fascinating journey. At Hindiyah Junction the line again crosses the Euphrates. Here are the largest irrigation works in Iraq, constructed in 1913 by British engineers. Towards noon we arrive at Hillah, an unimportant village in itself, but now the starting-point for a visit to the ruins of Babylon, three miles away. At a point 228 miles from Baghdad the line reaches the station of Ur Junction, in the neighbourhood of which are the ruins of the famous city of Ur of the Chaldees. Ur of the Chaldees, the birthplace of Abraham, is claimed to be the seat of the earliest civilization so far traced. The claim is supported by the results of excavation. Basra, 353 miles from Baghdad, is reached the following morning at 7.30 a.m. Basra does not lie on the Persian Gulf, but is connected with it by a natural canal, wide and deep enough to admit the passage of ocean steamers. Our journey is now at an end. We left Haydarpasa on Sunday at 9.40 a.m. and have arrived at Basra on Friday at 7.30 a.m.—118 hours. As the journey from London to Istanbul takes three days less a few hours, the entire journey from London to Basra requires approximately eight days.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |