|

|

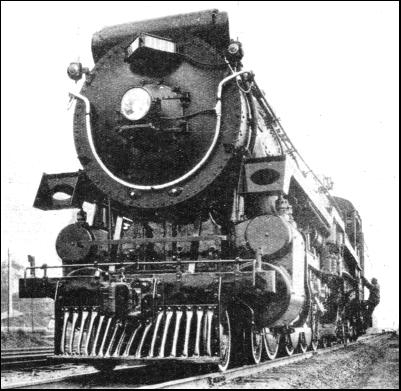

PICTURE the Windsor Station at Montreal. The "Trans-Canada Limited" express is waiting to begin its 2,886-mile journey to Vancouver. The train—long, smooth, powerful, the last word in mechanical efficiency—will soon be sweeping over the rails in a continuous pulsating rhythm to glide at last, quite unruffled by the feat, into Vancouver. "Red-caps"—name for porters in Canada, where "porter" is a sleeping-car attendant—are taking the luggage, while some of the passengers walk down the length of the express, which comprises ten passenger coaches ; two parlour-cars that go as far as Ottawa, a dining-car four standard sleepers, two ordinary compartment cars and a lounge car. At the head of the train is the locomotive She is a mighty monster of the 3,100 type—the pride of the Canadian Pacific shops which built her. Nearly 100 ft. in length, with tender included, she weighs 316-1/2 tons, this figure having been reduced to a minimum by the extensive use of nickel-steel parts. The engine has a tractive effort of 60,800 lb.; equal, that is, to 3,685 horse-power. There are eight pairs of wheels—a four-wheel leading truck, eight "drivers," and a four-wheel trailing truck. The driving wheels have a diameter of 6 ft. 3 in., and the cast nickel-steel cylinders are each 25-1/2 in. bore with a stroke ot 30 in The boiler supplying steam to these cylinders works at a pressure of 275 lb. per square inch. The coal capacity of the tender is 18-1/2 tons. The water tank holds 12,000 imperial gallons. A mechanical stoker lightens the duties of the fireman. From whatever aspect this superlative locomotive is viewed a feeling of awe is inspired by the triumph of engineering and design she epitomizes. Steam hisses, metal glistens, the passengers stand, held in admiration until they realize that they have only a few minutes to find their seats again. And now, with hardly a perceptible jerk, the journey has begun. It is "Au revoir Montreal !"

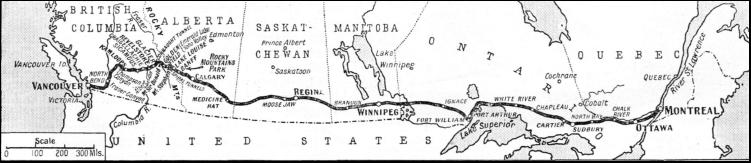

Montreal is not only the biggest city in Canada, but is also the commercial metropolis of the Dominion. A wonderful view of the city is seen from Mount Royal, with the broad waters of the St. Lawrence, spanned by huge bridges, in the distance. Beyond Ottawa, the capital, the route lies through Sudbury, the centre of the world's largest nickel deposits, discovered during the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Having left Sudbury, the "Limited" will thunder through the wild and still practically uninhabited territory north of Lakes Huron and Superior. The construction of the Lake Superior section of the line presented such difficulties that the eminent engineer, William van Home, described them as "engineering impossibilities." Their conquest is a story that ranks high in the history of railway engineering. The country to be traversed was a waste of forest, rock, and "muskegs" or swamps. Enemies of the railway declared that this portion of the line alone would require twenty years to build—if construction proved possible at all.

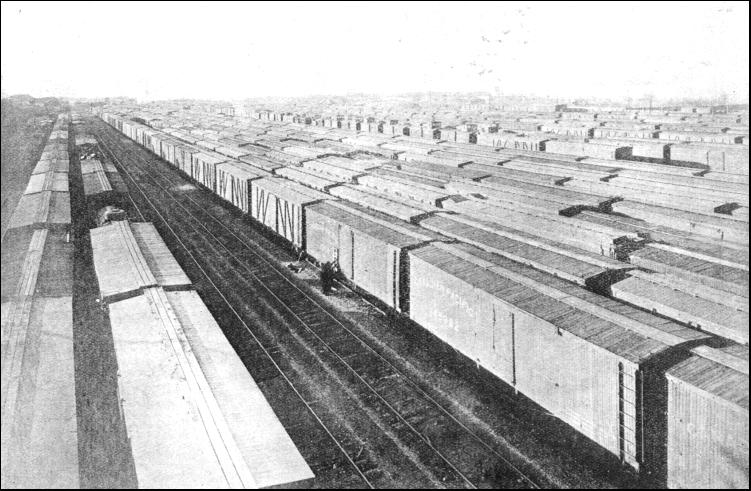

It was built in four years, but the labour was terrific. Of the £2,400,000 expended on this section of two hundred miles, approximately £400,000 were spent for explosive material. It seems incredible that the cost of building some parts of the line over which the train travels was little short of £140,000 per mile. The journey across Canada cannot fail to make the traveller appreciate the Dominion's debt to the railway. Cities owe their very existence to this narrow band of steel that spans a continent, while thousands of acres of prairie land have been opened up for agricultural development. By Lake Superior are the famous twin cities Port Arthur and Fort William, forming the outlet through which flows the great wheat crop of Western Canada. The railway, which has made accessible these inconceivably vast crops of grain, also handles the gigantic volume of wheat pouring in from Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta. Every year the railway company masses over 40,000 box cars with a combined capacity of over 1,570,000 tons, each of these capable of carrying over 60,000,000 bushels of grain per journey. Estimating that each car will make five journeys between the grain fields and the head of the Great Lakes or Vancouver, the company is in a position to shift 300,000,000 bushels of grain during the four months of the grain rush. This calls for considerable organization, as may well be imagined. The magnitude of the concentration of the box cars can be judged when it is known that if placed end to end they would stretch for 320 miles, and that it would take the fastest trans-continental train eight hours to pass this line. Eleven hundred freight locomotives are needed to keep the grain and normal traffic moving in western Canada.

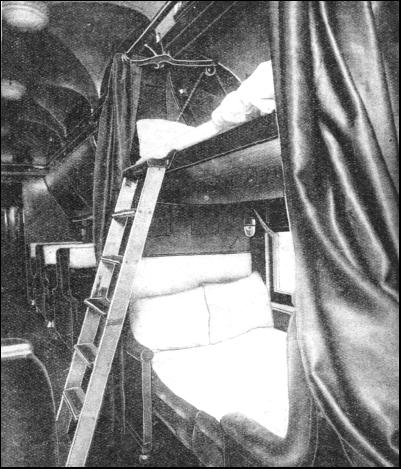

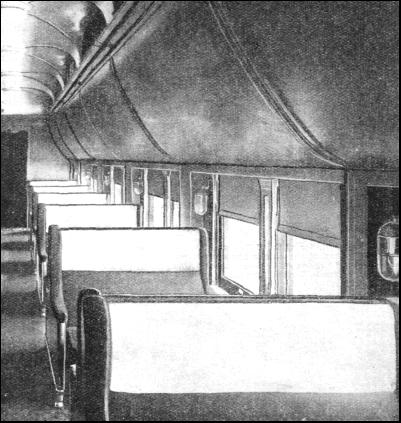

It is, of course, impossible to journey through this part of the Dominion without recalling the railway's mighty achievements, but passengers naturally want to explore the train. They can walk right through the cars to the solarium lounge car, the last coach on the "Trans-Canada Limited" express and invariably its most popular section. The coach contains a solarium room, fitted with vitaglass windows leading out to the observation platform. Apart from this there is the closed-in observation room proper, which has a buffet service, a small library, a smoking - room, shower - baths and ladies' lounge—all in one coach. The comforts and the conveniences of the "Trans-Canada Limited" make it comparable to an hotel on wheels. The train staff is a little army ; besides the driver—known in Canada as the "engineer"—and the fireman, the express has a conductor, trainman, sleeping-car conductor, one porter to each sleeping-car, a parlour-car attendant and the dining-car staff comprising chef, stewards, and waiters. The passengers have supper in the dining-car which seats thirty-six persons at a time. Afterwards, they quietly enjoy cigarettes and coffee while the train thunders steadily westward, towards the shores of Lake Superior. At last they turn in and sleep soundly If desired, a "valet service" will press suits while the owners sleep.

On the evening of the next day, Fort William is reached, and already nearly a thousand miles have been covered since the departure from Montreal. Four hundred miles west of Fort William comes Winnipeg, the gateway to the Granary of the British Empire, at which the train arrives on the third day out. Little more than fifty years ago Winnipeg comprised only the frontier settlement of Fort Garry, with a population of two hundred souls clustered round the Hudson Bay Company's post. Since the building of the C.P.R. it has become the largest primary grain market of the world, a prosperous, populous city, and the possessor of the biggest individual railway concentration yards in existence. Now the train is passing through endless miles of golden wheat fields, the prairie which the railway has miraculously transformed into an agricultural land of vast wealth, the home of hundreds of thousands of settlers. This is indeed the Kingdom of Wheat founded by the surveyors and pioneers of the railway. From the observation platform a great stretch of farms and grain fields, interspersed with large towns and stations surmounted by grain elevators, can be seen slowly unfolding. Regina, the Queen of the Kingdom, is the capital of the province of Saskatchewan, and the "Trans-Canada Limited" arrives there on the third day. A fifteen minutes' wait, and the train continues its journey. Regina, with its vast railway yard and sidings, has now become the principal railway centre between Winnipeg and Vancouver.

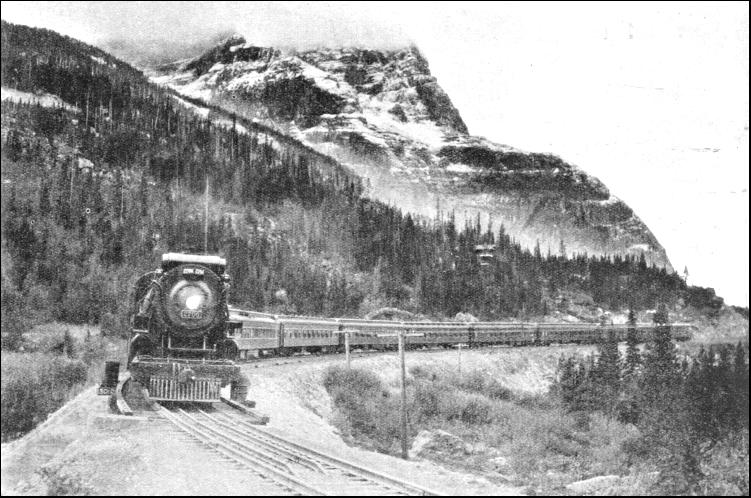

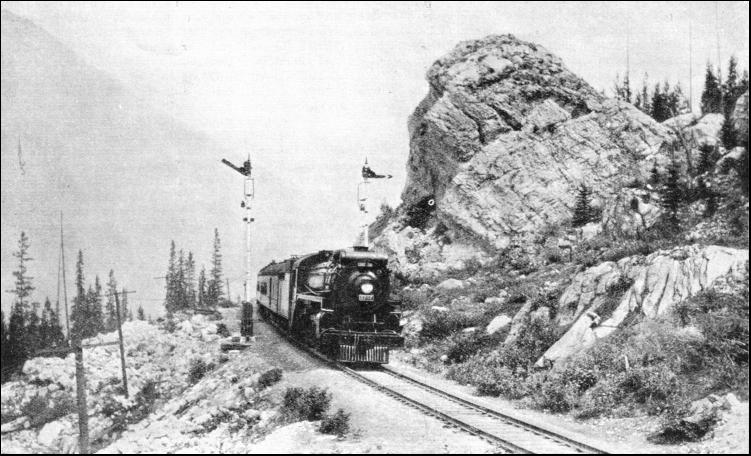

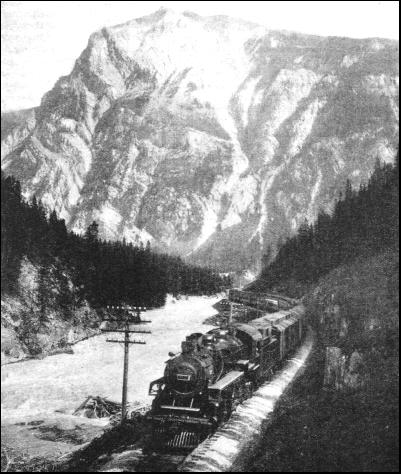

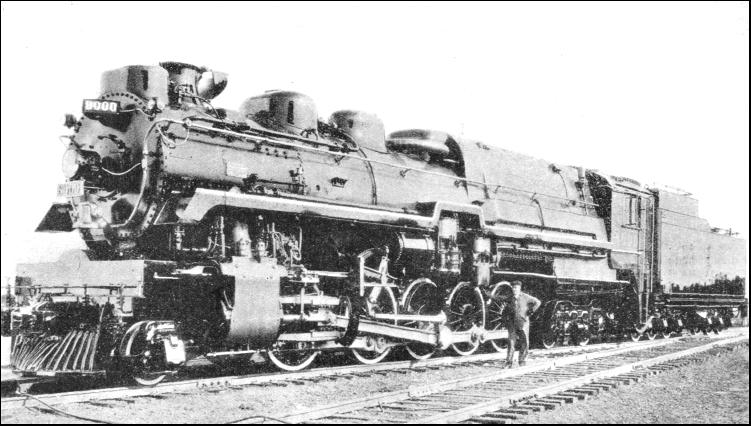

Gradually the prairie grows less uniform. Foothills are in evidence. Passengers begin to look out eagerly for the first faint outlines of the Rocky Mountains. These colossal ranges of towering crags formed the testing ground where the builders of the transcontinental line gave of their best. overcoming unparalleled difficulties and finally winning the applause of a whole civilization. Indeed, the mountain section of the Trans-Canada route must stand always as the supreme monument to the dauntless hearts and genius of its builders. For crossing the Rockies the locomotive is changed for a type recently introduced into the C. P. R 's service. This is one of the 8,000 class, built in the Company's shops at Montreal. This engine represents a new advance in the development of steam motive power towards maximum efficiency and is known as a "multi-pressure" engine, generating its steam in three separate stages and at three different pressures, thus permitting the economical use of high-pressure steam. This locomotive has no less than ten coupled driving wheels, and a few figures illustrate its enormous size. Its overall weight is approximately 392-1/2 tons, while the length of engine and tender combined is 99 ft. 3-3/8 in The ten driving wheels are each 5 ft. 3 in. in diameter. The two low-pressure cylinders, located outside the frame, using superheated steam at 250 lb. pressure per square inch, are 24 in. in diameter and 30 in. stroke. The high-pressure cylinder runs on superheated steam at 850 lb pressure per square inch, and is 15-1/2 in in diameter with a stroke of 28 in. The tender has a capacity of 12,000 gallons of water and 4,350 gallons of fuel oil, thus enabling the engine to undertake long runs without replenishing its supplies. Entering the mountains by the eastern portal, the "Gap," the train whirls the traveller into a realm of crags and canyons, glaciers and foaming torrents ; tree-skirted valleys and thunderous waterfalls extending westward for nearly 600 miles—a grand chaos of scenic glory. An express train crosses the Swiss Alps in five hours. This transcontinental flycr, the "Trans-Canada Limited," sending up strange echoes to grim hillsides, will take twenty-three hours to cross the ranges in Alberta and British Columbia. From the observation platform the onlooker is thrilled and overwhelmed by the wonderful views that flash into vision. Rearing heights, great purple chasms—all in one awe-inspiring cavalcade of Nature's grandeur. Few can help feeling that this country is much greater than men and that only because the gods of the mountains are kindly disposed have men been permitted into their fastness. On the north side of the line, as the express emerges from the "Gap," rears a fantastically notched and broken array of peaks, called the Fairholm Range, the greatest being known as the Grotto. To the south is seen the Goat Range, a series of massive, snow-laden promontories, rising thousands of feet, and penetrated by giant alcoves imprisoning a fairyland of shadowy-coloured vales. In the neighbourhood of the easily distinguishable companion peaks, the Three Sisters, a curious group of pillars known as the "Hoodoos," suddenly appears. Beyond them, north of Banff station, looms the mighty bulk of Cascade.

From Calgary to the "Gap" the railway closely follows Bow River. Winding and climbing, the line now enters this natural approach. The climb, up is long and slow. As the rails twist tortuously in and out of crags and terraces, the engine labours to the summit at Stephen, at which point the line lies at 5,329 ft. above sea level, having climbed 1,901 ft. in 123 miles. While the railway winds along the course of Bow River, between Banff and Lake Louise, dense forests, over which mountains tower on either side, can be seen from the carriage window. Far to the south the passenger has a view of the dream-like snow-clad peaks that enclose Simpson's Pass, and he cannot help wondering what it would be like to ascend these magnificent heights. The train goes on towards the "Great Divide," whence the waters from the glaciers separate to course down eitlier side of the mountain before heading for the Arctic or the Pacific. It is a vast marsh and the summit was conquered without tunnelling or erecting protective snowsheds. The descent, however, falls away so suddenly that to keep the gradient within limits tunnelling was employed to a large extent. As originally planned, when time and money were scarce, a temporary line was constructed involving a steep grade of 1 in 23, for 4 miles. But when competition enforced drastic revision the route on "Big Hill," as the climb was nicknamed, was abandoned. Instead, by an ingenious relocation of the line, including the boring of two spiral tunnels on opposite sides of the valley, the gradient has been flattened to an average of 1 in 50, at the cost of 4-1/2 miles increase in distance.

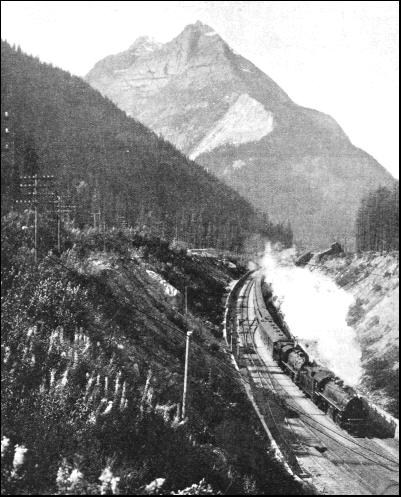

Westbound, the ''Trans-Canada Limited" enters the first tunnel, and when the track has completed an entire circle within the mountain, emerges into daylight again. Then the express swings to the east, crosses the river and passes through the second tunnel under Mount Ogden. In this tunnel, also, the train turns another complete circle, finally issuing from the heart of the mountain to continue west to Field. The line here doubles back upon itself twice and forms a rough figure "S" bend. About 6,000 ft. above Field, the gateway to the famous Yoho National Park, and Yoho Valley, one of the most beautiful spots in the Rockies. Mount Stephen rears skywards. At the foot of the mountain the Kicking-Horse River rushes and tumbles on its way to join the Columbia. The journey between Lake Louise and Field, a matter of twenty miles, brings a startling realization of the unavoidably steep gradients, and of the engineering difficulties encountered. Westward from Field, the route runs parallel with the turbulent Kicking-Horsc River. Then the train plunges down into the Kicking-Horse Canyon, where the mountain walls are practically vertical From the observation car can be heard the roar of the river boiling over the rocks below As the wheels thud over the metals, the reverberations mingle with the continual echoes of the angry stream. Golden comes next. It is the fourth day of the "Limited's" journey. The traveller is now in the contrasted calm of the mighty Columbian mountains. Between Golden and Glacier, the climax of the mountain splendour reveals itself. First there is the magnificent eastern thrust of the Selkirks, a dominating array of peaks culminating in the lofty pinnacle of Sir Donald. Among bursting cascades of mountain torrents, narrow gorges, precipitous canyons and dizzy abysses, the giant train is reduced by comparison to a crawling worm of steel. Overhead, white against a clear blue sky, fly streaming pennons of smoke. Sunlight catches the slope of a mountain—pines, crags, and streams are tinted with shades of gold. Mount Macdonald of the Selkirks lies ahead. The train will soon be passing through the longest tunnel in Canada, five miles in length from portal to portal. When the railway pioneers were con fronted by the implacable barrier of the Selkirks even local Indians could not suggest a way through. Major Rogers accordingly set out to explore. He found rivers resembling a succession of weirs, and ravine after ravine dropping sheer for several hundred feet. Rogers spent many days of perilous mountaineering before he discovered and followed a rift which led him through the great range. To-day that rift is called "Rogers Pass." For twenty-five years the Canadian Pacific trains threaded their way through this pass. But the wedge-like route between the mountains forced the trains to struggle up 1,768 ft. in 45 miles and then descend 2,857 ft. during the subsequent 22 miles. Besides the tremendous strain imposed on the locomotive, and the limitations of traffic capacity, the track was exposed to snow-falls and avalanches, which perpetually threatened to block the line. Owing to the increasing volume of traffic and the competition of other lines, the company demanded that its engineers should locate another route. The problem of the gradient was finally overcome by the boring of the Connaught Tunnel. Above the crown of the bore of this tunnel there is about one mile of rock, forming the body of the peak. Fifty feet to one side of the centre line of the main work a preliminary tunnel was driven in order to facilitate and to speed up construction ; by forcing galleries out at right angles from the temporary tunnel, thirty-two working faces were possible instead of only two. The approaches to the tunnel also necessitated heavy excavation. Having passed through this tunnel the train slackens speed prior to a halt at Glacier station. Above is the Illecillewaet glacier, a vast plateau of gleaming ice, framed in a dark forest of giant cedars, hemlock and spruce trees, scarred by crevasses, and covering an area of about ten square miles For a considerable portion of the journey, the "Trans-Canada Limited" pursues the course of the Illecillewaet River, which, tumbling along boulder-strewn gorges, rushing and foaming, pours in a turbulent and foam-flecked torrent from its icy source into the waters of the Columbia, two thousand feet below. During the revision of the alignment after the tunnelling of Mount Macdonald, the course of the Illecillewaet River was diverted, owing to the fact that in spring, when waters are in flood, they represent a serious menace to the rails. Accordingly, the engineers had either to bridge or to divert the river. Diversion was favoured, and an embankment of 900,000 cubic yards was constructed, and a huge channel dug parallel to the track to offer a new bed.

Beyond Revelstoke the express crosses the Gold Range through Eagle Pass, where, at Craigellachie, an obelisk commemorates the completion of the Canadian Pacific Railway and the driving of the last spike of the great line. The spike was driven in at Craigellachie by the late Sir Donald Smith (Lord Strathcona) on November 7, 1885, and the first transcontinental train ran in 1886. Vancouver is drawing steadily nearer, but there are still the Thompson River Canyons to traverse. They, in turn, lead on to the celebrated Fraser Canyon—the only practicable passage for the railway. As the train passes along the constricted terraces the passengers—comfortably reading the current newspapers—may not appreciate how great the difficulties of blasting away along the slopes of these canyons must have been. At Lytton the canyon widens, to admit the Fraser, the chief river of British Columbia. This river comes pouring down from the north between two great lines of mountain peaks, and its turbid flood soon engulfs the bright green waters of the Thompson. This section of the railway again exemplifies the skill and courage of the builders. The line follows the canyon at a considerable height above the river bank, while the track itself has been hewn through solid rock. At Hell's Gate, attention is arrested by a fine view of a spectacular cataract formed by the sudden compression of the river between two jutting promontories, whence it escapes through a bottle-necked outlet. Beyond Yale, occupying a cleft above the river, in a deep recess in the mountains. Here the canyon in which the train has been travelling for so long begins to fall away, and now come the valleys through which the express swiftly sweeps on towards Vancouver. The time is nearly up, the destination at hand, and although the passengers cannot all visualize the difficulties of constructing the route which the express takes, they feel proud of the engineering triumph which has rapidly transported them over thousands of miles. Now come the outlying districts of Vancouver. There is a considerable bustle in consequence. People begin packing their light luggage. Though they are still on the train, their journey is over. It has been a dreamlike experience, an unforgettable episode—crossing the entire stretch of Canada in 89-1/4 hours ! Here is a view of Vancouver itself. The city ranks as one of the principal ports on the western seaboard. Built on Burrard Inlet, the fully-sheltered harbour has a favourable place on the world's highway of commerce and is developing into an important shipping centre. The great "Trans-Canada Limited" express is slackening speed, and gliding into the station. A few days later it will return to Montreal The carrying of passengers in complete comfort, even for 3,000 miles, by no means gives the full significance of the railway system over which the "Trans-Canada" passes The journey from Montreal to Vancouver, perhaps the finest panoramic spectacle the world has to offer, also makes a thoughtful passenger realize the supreme importance of the railway to the industrial and commercial existence of Canada. Over half a century the railway has expanded by 20,000 miles of line. The single track of early pioneer years has been converted into a double track from ocean to ocean ; branch lines and connexions have been extended north, south, east and west. Where the rails have been driven, settlements, towns, and cities have grown up. Many of the towns the express passed on the route were scarcely in existence fifty years ago.

The iron-horse has gone on steadily conquering Canada since the running of the first express in 1886, making the country habitable for an ever-increasing population; and the "Trans-Canada Limited" itself roars through the country-side as the natural heir of the cumbersome old-time trains hauled by ancient locomotives with their grotesque spark-arresters on the smoke-stacks. The original alignments of the line have been greatly improved in the course of time ; huge sums of money have been lavished upon new tunnelling, bridging and the diverting of streams. Speed and more speed has been demanded, and the railway has always met that demand with improved locomotives. To-day it is the 8000 type engine that hauls the long-distance expresses over the mountains, where spiral tracks in narrow defiles have been supplanted by tunnels which pierce giant buttresses, and trestle bridges have given way to steel. Important additions have been made to the storage capacity and equipment of the grain elevators—the type that the "Trails-Canada" passes as it rushes through the various stations of the prairie towns. Beside the railway telegraph lines run the cables which link up two hemispheres. Stations such as Winnipeg have grown from rough wooden structures to magnificent buildings. The workshops at Montreal built the express locomotive pulling the "Trans-Canada Limited," and these engine works have become the first in magnitude on the American Continent, and turn out the largest and most powerful locomotives in the whole of the British Empire. Since the coming of the railway, vast areas of mineral wealth have been opened up for the prospector. In Ontario is found the third largest gold mine in the world—the Hollinger Gold Mine. Only one fifth of the mineral area of the Dominion has been exploited. During the building of the trans-continental line, the famous Sudbury nickel-copper area was developed ; it now ranks as the chief source of the world's nickel supply, and of late has been also producing copper in large quantities. In British Columbia, beyond the Rockies, great lead-zinc deposits are being worked. Agriculture has been and still is the basic element in the progress of the Dominion. The opening to the settlement of the seemingly limitless plains of the West was the first act in the drama that began after the actual building of the railway. Before the prairie was opened by the steel highway, Canadian agriculture was confined to the east—to the river valley and coastal regions of the Maritime Provinces. Now, an agricultural empire has arisen which has changed the entire balance and aspect of the Dominion. The call of the west and the wheat-lands was heard throughout two continents, and the human inflow from Great Britain and Europe has been the main feature in Canada's progress during the last three decades. In British Columbia, too, the uplands and coastal areas have been stirred to life by the coming of the locomotive. Vancouver was brought into being by the Canadian Pacific Railway. Prior to its selection as the western terminus and port of the trans-continental line, it was but a tiny clearance in the bush. North of Quebec and Ontario a long wedge of pioneer settlement has entered into the belt lying between James Bay and the Upper Great Lakes. In Ontario and Quebec production, especially in dairy-farming, has increased rapidly. Besides the fostering of agriculture and mining, the railway has encouraged the vast industry of paper making and pulp. From the endless forestlands of Canada the freight engines can be seen drawing train after train of bolster wagons loaded with timber for the paper mills. The newspapers and journals of Canada and the United States provide an inexhaustible market for these mills. The railway has also assisted the widespread development of water-power, which, cheap and plentiful, has attracted from abroad big industries whose output swells Canada's export trade. But, apart from the mineral wealth brought to light, it is in the development of the agricultural regions that the importance of the railway to Canada's prosperity has been shown.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |