|

|

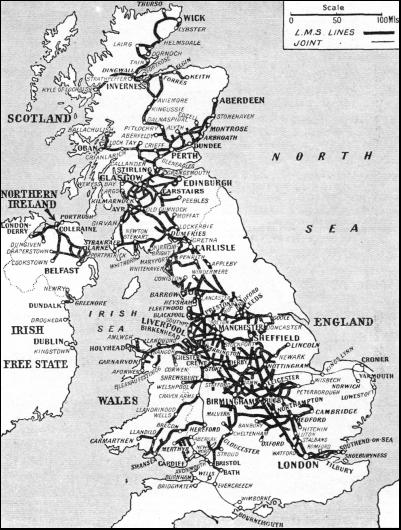

Of the four great railways formed in 1923 by the Railways Act of 1921, the London, Midland and Scottish is the largest. It is the only British railway serving England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland. Excluding the Irish Northern Counties Committee and certain joint lines, its route mileage is 6,758, and its total length, reduced to single track, is 18,921 miles. The L.M.S. is made up of seven constituent and twenty-seven subsidiary companies. The seven constituent companies absorbed in 1923 were the London and North Western, the Midland, the North Staffordshire, and the Furness Railways in England, and the Caledonian, Glasgow and South Western, and Highland Railways in Scotland. Many of these had already assimilated scores of smaller lines. The London and North Western, for example, was made up of about a hundred companies. Its last acquisitions were the Lancashire and Yorkshire and North London Railways, taken over on the eve of the general amalgamation. Some years before the war of 1914-18 the Midland absorbed the London, Tilbury and Southend and the Belfast and Northern Counties Railways. Of the constituent companies the London and North Western, generally accorded the title of "the premier line." was the largest, with a route mileage of 1,807 in 1921. Next in order of length were the Midland, with 1,529, and the Caledonian, with 896 route miles. The corresponding figures for the other constituent companies were Highland 485, Glasgow and South Western 449, North Staffordshire 206, and Furness 115. The route mileage of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway in 1920 was 533.

The subsidiary companies included the Wirral, serving the Cheshire peninsula of that name; the Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction, once known as the East and West Junction; the Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Joint, on which ran the Stranraer boat-expresses, via Dumfries; and the Maryport and Carlisle, and Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith, in Cumberland. Some of these railways, even in the days of their independence, were worked by the larger companies. On the Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith, for example, the passenger service was run by the London and North Western, and the freight service by the North Eastern Railway. At the present day (1935) the L.M.S. is divided into the Western Division (including most of the former London and North Western Railway), the Midland Division (former Midland Railway), the Central Division (Lancashire and Yorkshire), and the Northern Division (including all the three Scottish lines taken over in 1923). Some idea of the extent of the L.M.S. system may be gathered from the fact that its main lines extend from London to Wick, in the far north of Scotland and 729 miles from Euston. Even this is not the extreme limit of the L.M.S., as a branch line runs from Wick to Lybster, 742½ miles from Euston. The most northerly railway station in Great Britain is Thurso, on all L.M.S. branch of the main line to Wick. diverging at Georgemas.

The main line of the former London and North Western Railway runs from Euston to Carlisle, 299 miles distant, by what is known as the West Coast Route. Its main intermediate stations are Rugby, Stafford, Crewe, and Preston. The most important of its numerous branches are those from Rugby to Birmingham (originally a continuation of the main London and Birmingham line); from Crewe to Manchester, to Chester and Holyhead (for steamers to Ireland), and to Shrewsbury (for the joint line referred to later); and from Sutton Weaver Junction, about sixteen miles north of Crewe, to Liverpool. The country of the former North Staffordshire Railway lies to the east of a line drawn from Stafford to Crewe. The North Staffordshire line from Colwich, a junction on the main West Coast Route six miles east of Stafford, provides the shortest route (183½ miles) between London and Manchester, though the fastest Euston-Manchester expresses take the five miles longer route via Crewe. From Carnforth, twenty-seven miles north of Preston, the main line of the former Furness Railway skirts the Lake District and runs to Barrow-in-Furness and Whitehaven. The former Midland main line from St. Pancras to Carlisle, 310½ miles in length, runs via Leicester, Sheffield, Leeds (for Bradford), and Hellifield. A loop-line takes in Nottingham. and another loop avoids Sheffield. From Trent Junction, 20 miles north of Leicester, another main line runs to Derby and Manchester. From Derby an important cross-country line strikes south-west to Birmingham, Bath, and Bristol.

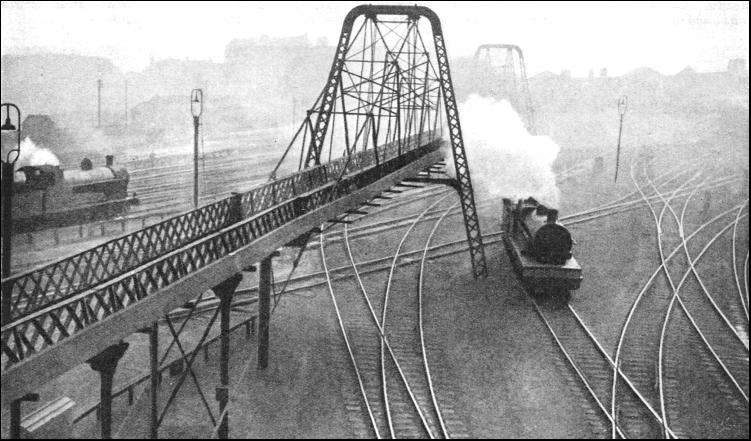

At Carlisle Station the main line of the Midland Division meets that of the former London and North Western. Running across the two main routes is a maze of lines uniting Lancashire and Yorkshire. One of these is the shortest line from Liverpool to Manchester - the oldest part of the L.M.S. system - and its continuation across the Pennines to Leeds. Many of the others, as might be expected, once belonged to the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, these include another line from Liverpool to Manchester, which also is continued across the Pennines. From Carlisle the main line - formerly belonging to the Caledonian Railway - runs north to Glasgow (102½ miles), Edinburgh (101 miles), Perth (150¾ miles), and Aberdeen (240½ miles). The route of the former Glasgow and South Western Railway from Carlisle to Glasgow, via Dumfries, is thirteen miles longer than the Caledonian route; it is taken by the London-Glasgow expresses via the Midland Division of the L.M.S. From Dumfries there branches off the line to Stranraer (for Northern Ireland). The Highland line, uses Perth as its starting-point, though it really begins at Stanley Junction, over seven miles to the north. It is not possible here to do justice to the numerous minor branches of the L.M.S. One of these, however, calls for mention by reason of its length - the Central Wales Line to Swansea from Craven Arms, on the Shrewsbury-Hereford line. This picturesque branch is ninety-five and a half miles long.

In conjunction with the Great Western Railway the L.M.S. operates the busy cross-country line from Shrewsbury via Craven Arms to Hereford, for Newport, South Wales, Bristol, and the West of England. It is joint owner with the Southern Railway of the Somerset and Dorset Joint, whose main line runs from Bath to Bournemouth West. The Cheshire Lines, operating an express route between Liverpool and Manchester, via Warrington, in addition to several branches, belong jointly to the L.M.S. and the L.N.E.R. Another joint L.M.S. and L.N.E.R. line is the Midland and Great Northern Joint, extending from Saxby and Peterborough to King's Lynn, Cromer, Yarmouth, and Lowestoft. In addition, there are four L.M.S. and L.N.E.R. Joint Committees, interested in the working of various minor joint lines. The L.M.S. is thus connected with every one of the other great British railways. In Ireland the L.M.S. owns and works the Northern Counties Committee (formerly the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway), whose main line is from Belfast to Londonderry. The L.M.S. also owns the Dundalk, Newry and Greenore Railway, worked by the Irish Great Northern Railway; and it is jointly interested with the latter company in the narrow-gauge lines of the County Donegal Joint Committee, and of the Strabane and Letterkenny Railway. In view of the wide ramifications of the L.M.S. system it is not surprising that its route mileage exceeds that of any of the other great British railways. Indeed the mileage compares favourably with that of the great overseas railways. Although, for example, the Canadian Pacific Railway extends across the North American Continent, its track mileage is not proportionately in excess of that of the L.M.S.

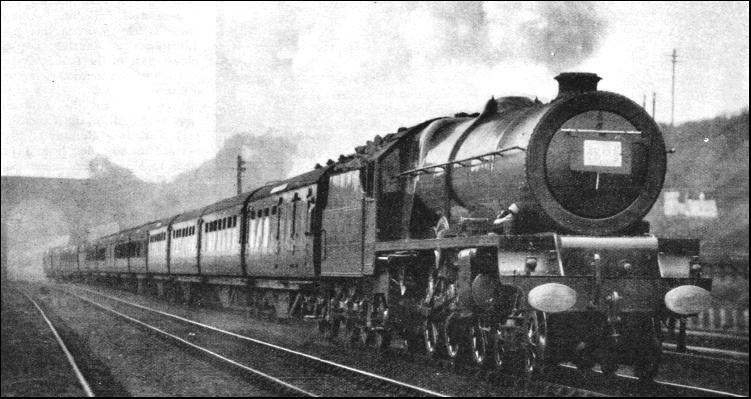

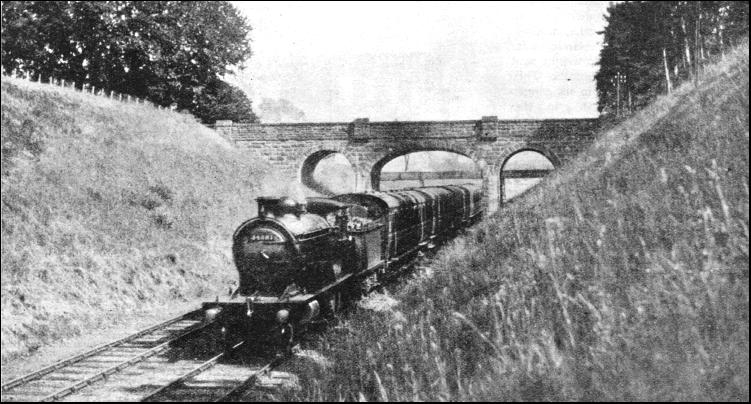

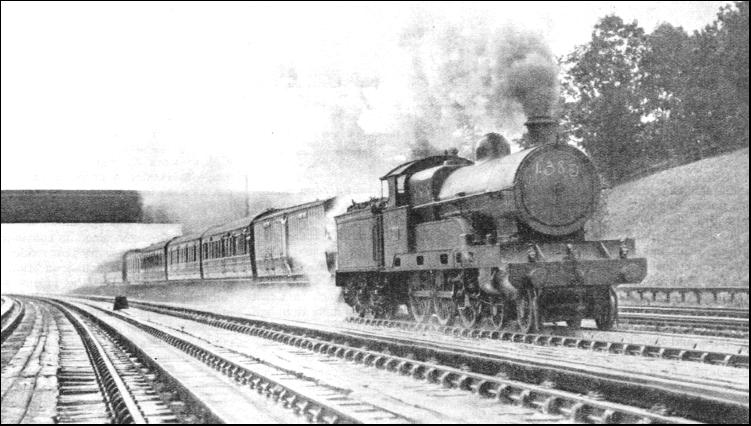

But it is not in length alone that the L.M.S. can claim distinction. It possesses the largest stock of locomotives, carriages and wagons. On January 1, 1934 it owned 8,004 locomotives, 24,023 coaching vehicles, 250 electric-motor vehicles, twenty-two steam rail-motors, three Diesel rail-cars, 270,441 merchandise and mineral vehicles, and 15,584 service vehicles. Under the last heading are included ballast wagons, coal and coke wagons for the use of the locomotive department, gas holder trucks, travelling cranes, tool vans, timber, rail, and sleeper trucks and breakdown cranes. Twenty-two locomotives are reserved for departmental use. In addition, the company owns 2,088 parcels and goods road motor vehicles, and over 8,400 horses. It possesses also forty-nine steamboats (four jointly owned), 537 miles of canal, and docks, harbours and wharves, with a total length of approximately 93,000 ft. of quay. Of these Barrow, Grangemouth, Fleetwood, Holyhead, Heysham, Garston, Ayr, and Troon are the largest. Over 104 miles of track are electrified. Of British railways, the L.M.S. handles the largest passenger and goods traffic, and earns the largest income, its weekly traffic receipts averaging over £1,000,000. It owns numerous hotels, including some of the finest in the country. The passenger train services are generally fast and frequent. The company has the largest number of long non-stop runs in Britain, one of these - that of the up "Royal Scot" from Carlisle to Euston - being a world's record for over nine months of the year. The 299 miles are covered every weekday in five and a half hours. The number of trains booked at fifty-five miles an hour and upwards from start to stop is greater than on any other British railway. In the spring of 1935 the daily mileage at sixty miles an hour and over from start to stop reached the figure of 1,235, all on the lines of the former London and North Western Railway. The fastest L.M.S. train is the 5.25 p.m. from Liverpool to Euston, which covers the 152.7 miles from Crewe to Willesden Junction in 142 minutes, at an average speed of 64.5 miles an hour. At the time of writing (1935) its schedule is the second fastest in the British Isles, being beaten only by that of the "Cheltenham Flyer," between Swindon and Paddington.

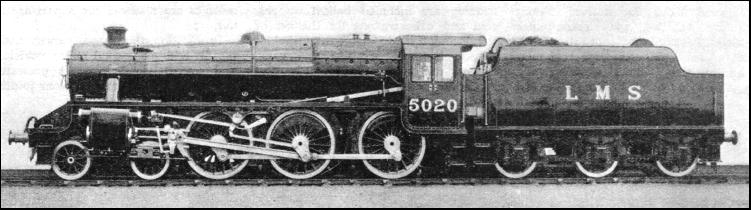

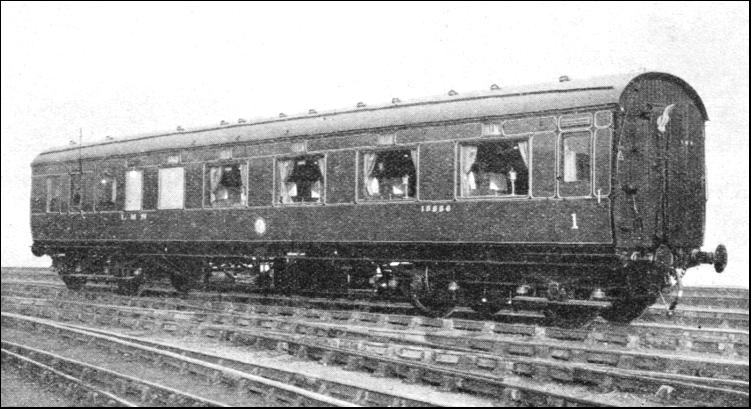

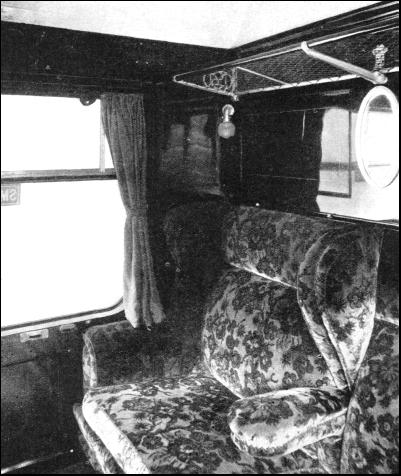

The locomotives are up to date and efficient, large numbers of passenger and freight engines having been built in recent years. The L.M.S. is the only British railway which employs compound locomotives in large numbers. The largest L.M.S. locomotives are not, however, compounds. Experiments are constantly being made with new types, including turbine locomotives, and rail-cars of Various kinds. The rolling-stock is second to none, the company having inherited the traditions of the former Midland Railway in this respect. Midland influence is also seen in the crimson lake which is now the standard colour for passenger coaches and for many classes of express locomotives. Long-distance trains are equipped with both open vestibule and compartment corridor coaches of the most modern type. The make-up of the "Royal Scot" is renowned. The "Merseyside Express" and the "Ulster Express" have first-class lounge cars, in addition to the ordinary accommodation, and special luxury coaches are found on certain other services. Observation cars are run on scenic routes in Scotland and North Wales. First and third-class sleeping cars form part of the equipment on many of the night expresses. Although it is the proud and well founded boast of the L.N.E.R. that, by virtue of ownership of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, it is "the oldest firm in the railway business," the beginnings of the London, Midland and Scottish system go back nearly a quarter of a century before that September day in 1825 when the first public railway was opened. The Sirhowy branch of the London and North Western, in North Wales, was originally a plate way - with the unusual gauge of 4 ft. 4 in. - incorporated as early as 1802, although locomotives were not introduced until 1829. Another pioneer line now vested in the L.M.S. was the Kilmarnock and Troon Railway, incorporated in 1808 and opened in 1810. It was the first railway in Scotland to use a locomotive, which was experimentally introduced in 1817, but withdrawn as its weight was too great for the light plate rails. This line also was unorthodox in its gauge, partly 4 ft. and partly 3 ft. 4 in., the latter section being laid with fish-bellied rail set in iron chairs spiked to stone sleepers. Several other railways incorporated before the Stockton and Darlington now form part of the L.M.S. system.

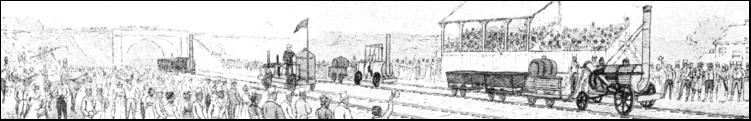

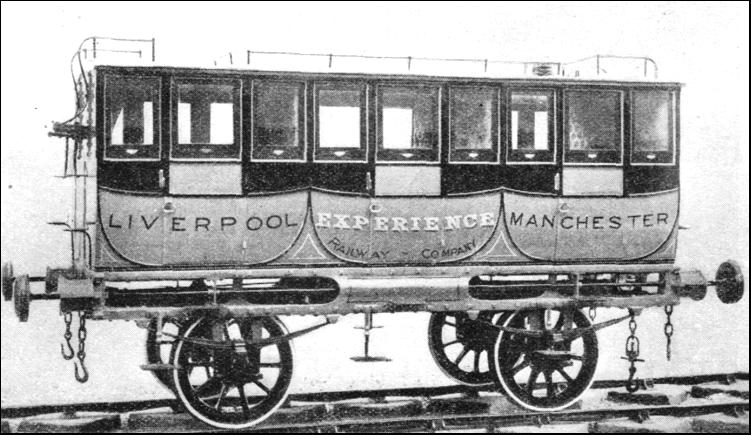

These early lines were more numerous than is generally realised, since no fewer than twenty-three companies obtained powers for the construction of horse operated railways before the Stockton and Darlington was incorporated. Although the traces of most of them have disappeared, some have become embodied in the existing great railways. Included in the L.M.S. is the Liverpool and Manchester, the second public railway in the world. Within five years of the opening of the line passenger receipts amounted to ten time the promoters' estimates, and goods earnings to three times as much as had been reckoned on. Through its ownership of this line, the L.M.S. claims to be "the oldest-established firm in the railway passenger business."

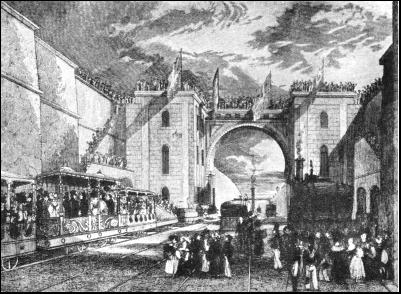

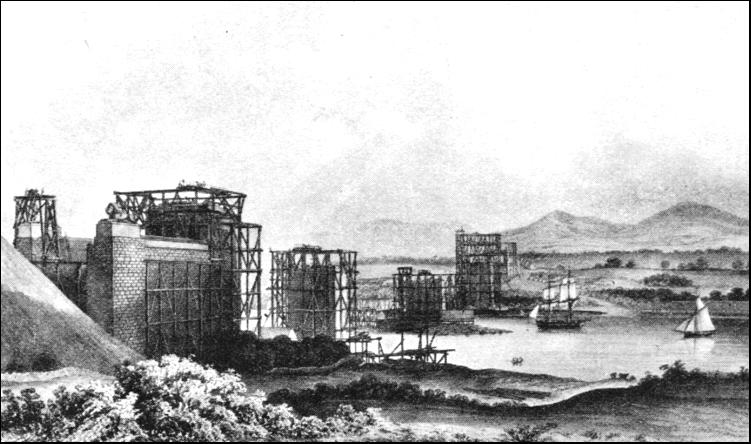

The real history of the L.M.S. thus begins with the Liverpool and Manchester, which was incorporated in 1826. But this was a year later than the Cromford and High Peak Railway, which was absorbed by the London and North Western in 1887, and, despite its short length, is unusually interesting from both the historical and engineering standpoints. It was built to connect the Midland Counties with Liverpool and Manchester, the mountainous nature of the district making a canal out of the question, and it joined the Cromford Canal with the Peak Forest Canal at Whaley Bridge. The line is in part as much as a thousand feet above sea level, this elevation being made possible by the use of a number of inclined planes with gradients as steep as 1 in 7½ and 1 in 8½, on which traffic was originally worked by fixed engines. On the intervening sections, horses at first were used. The line, which was opened in 1830, was thirty-four miles long. The seven miles section between Whaley Bridge and Ladmanlow has been abandoned, but the five and a half miles stretch between Parsley Hay and Hindlow remodelled for passenger traffic in 1894, now forms part of the branch from Ashbourne to Buxton, and is one of the most picturesque lines in the country. But to return to the Liverpool and Manchester - This project arose out of the delays and uncertainties of water transport between the two cities, as well as the excessive tolls charged by the canal companies, which had not yet begun to realise that their former monopoly was passing. The original scheme was for a line thirty-one miles in length, with a Liverpool terminus at the Wapping Docks. Since many of the most eminent engineers of the day still doubted the capabilities of the locomotive, the mode of traction was not definitely decided on. The first Act of Parliament even contained the uncommon provision that locomotives were not to be used in towns. This restriction was subsequently withdrawn; the route was slightly modified and shortened, and the success of the "Rocket" at the Rainhill Trials of 1829 definitely convinced the directors of the possibilities of locomotive traction. The line, which was opened on September 15, 1830, with great pomp and ceremony, possessed two unusual engineering features, Chat Moss and the Olive Mount Cutting at Edge Hill. Chat Moss was the surviving remnant of a belt of fen, uncultivated mosses, and morasses which at one time stretched across England from the Mersey to the mouth of the Ouse, and was described by the author of "Robinson Crusoe" as being "indeed frightful to think of, for it will bear neither horse nor man, unless in an exceedingly dry season, and then so as not to he travelled on with safety."

Parliament was told that the Moss was too formidable an obstacle to be crossed, while another sceptic said that if it were possible the cost would be well over a quarter of a million. The expense proved to be only £28,000, and the method adopted was to spread hurdles interwoven with heather so as to form a floating road, and to construct a watercourse (drainage being impracticable) out of empty tar barrels covered with clay. On this foundation the weight of track and trains was not only safely supported, but also the section "eventually proved to be the most satisfactory part of the line," although its abandonment had at one time seriously been considered because of the difficulties involved. The Olive Mount Cutting, which has been illustrated in so many of the early railway prints, is two miles long and more than a hundred feet deep in parts, and involved the removal of nearly half a million cubic feet of stone. Originally constructed to take two tracks, it was afterwards widened to accommodate four. In 1845 the Liverpool and Manchester Railway was amalgamated with the Grand Junction Railway, which extended from Liverpool and Manchester, via Crewe, to Birmingham, where it linked up with the London and Birmingham line. A year later the three undertakings, together with a number of other lines, including the Manchester and Birmingham, became the London and North Western. The first section of the London and Birmingham, between London and Tring, was advertised to open in 1837, and by September in the following year through trains were running the whole distance to Birmingham. After 1846 the London and North Western Railway proceeded to expand apace. In 1858 Parliament sanctioned the absorption of the Chester and Holyhead Railway. The following year the London and North Western leased the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, now an integral part of the West Coast route to Scotland.

The years 1864-67 were known as the "amalgamation years," because of the number of systems taken over. As late as the eve of its dissolution the "premier line" assimilated two important railways, as stated earlier. The nucleus of the Midland Railway system owes much to William Hudson, the "railway king." He was the first to realise, and to put into practice, the idea that railways could best be worked as large-scale undertakings; and that amalgamation, which would yield centralised ownership and management, was therefore necessary. Hudson was a native of York, where he had made a respectable fortune as a linen draper, and became associated with George Stephenson. Among his companies were the York and North Midland and the Midland Counties, and in 1844 these two systems were amalgamated with the Birmingham and Derby, which had become a competitor of the York line. The fusion of the three, all of which had been incorporated in 1839, was the beginning of the Midland Railway Company. The Midland grew in importance, but remained for a time only a provincial undertaking, the London terminus at St. Pancras not being opened until October, 1868, although previously Midland trains had reached London over the Great Northern tracks. After the company had come into possession of its own terminus it adopted a progressive policy, largely due to the enterprise of the late Sir James Allport, one of the most celebrated of all English railway managers.

On April 1, 1872, Allport created a sensation in the railway world by announcing that thenceforth the Midland would carry third-class passengers by all trains, thus being the first railway in the kingdom to admit the "penny-a-miler" on terms of equality. Another innovation followed three years later, when the second-class was abolished. One reason for this step is said to have been that in 1874 the company introduced Pullman cars into England, and, since a supplementary fee was charged for their use, the result was in effect to have four classes. But this could have been only a minor cause, the main reason being the foresight of the general manager. Incidentally, the company abolished Pullmans at a later date, when they had been adopted on the Southern lines. That the Midland was the first to admit third-class passengers to all trains, and to abolish the second-class, is known to everyone who has a smattering of British railway history. But it is not generally known that the second-class was abolished many years before 1875 on another line forming part of the system. This railway was the Sheffield and Rotherham, which was opened in 1838, and was the first to do away with the intermediate class. But, while under the Allport regime the third-class passenger was given almost the same degree of comfort as the first-class passenger, on the Sheffield and Rotherham he had to be content with "mere trucks with deal forms to sit upon, which were painted green." But although the Midland grew out of Hudson's amalgamations, the first portion of the system constructed was the Leicester and Swannington Railway, which, as happened with so many of the early lines, was built with the primary idea of cheapening the conveyance of coal. It was opened in July, 1832, and one of its original features was a "self-acting incline" near the Bagworth collieries. The Leicester and Swannington (Leicester was one of the six cities whose coats-of-arms were embodied in that of the Midland) is noteworthy for two innovations; the locomotive steam whistle was first heard on its lines, and it ran the first excursion train on record.

The generally accepted story is that one of its engines, the "Samson," ran over at a level crossing a cart laden with eggs and butter, and that to avoid a repetition of such accidents, it was suggested to George Stephenson by the manager of the line, who afterwards became the first general manager of the London and Birmingham Railway, that it might be possible to equip the locomotives with a steam-operated whistle. Stephenson approved the idea; a Leicester musical instrument-maker named Ashlin Bagster devised a "steam trumpet." When the device was fitted to the "Samson," it proved so successful that it was not only made part of the equipment of the whole of the company's locomotive stud, but, was also adopted by every other railway. Credit for the invention is therefore due, not to Stephenson, who never laid claim to it, but to Bagster. The first excursion train was run on July 20, 1840, and was organised by the Nottingham Mechanics' Institute, whose members desired to visit an exhibition at Leicester. When the railway company received a list of intending passengers, it arranged to run a special train at half fares, and a week later the Leicester Mechanics' Institute was granted similar facilities for a visit to an exhibition at Nottingham. These two trains were so successful that in the following month the railway company ran excursions of its own, one from Leicester and intermediate stations to Nottingham, and the other in the reverse direction. No fewer than 2,400 people booked for the latter; they were accommodated in a single train composed of sixty-five coaches and hauled by numerous engines.

Out of these beginnings there grew the travel business of Thomas Cook (which also originated in an excursion on the Midland) and the whole vast traffic at cheap rates, which in Great Britain today makes up more than half of the main line passenger bookings. When the Midland Railway Company was formed in 1844, it became the largest single undertaking in the country, if not in the world, in point of mileage. Its tracks, then 181½ miles long, were partly laid on stone blocks and partly on longitudinal sleepers, with a section a mile and a half long laid on bridge rails. Considerable savings were the immediate result of fusion. For instance, the three separate locomotive "shops" at Derby were merged into one, and were placed under the supervision of the celebrated Matthew Kirtley, who remained in charge until his death in 1873, when he was succeeded by S. W. Johnson. Both engineers left their mark on Midland locomotive design. Kirtley was a pioneer of standardisation; when he took over control he found a stud of ninety-five engines, all of which were four-wheelers. He immediately introduced six-wheelers, although it was not until 1851 that he built his first engine at Derby. When it became evident that the policy of "third-class by all trains" would lead to an immediate increase in their length and weight, he was so well prepared for the resulting demand on his department that on the very day of the new departure, he had sixty-eight new engines ready, specially and successfully designed for the work.

The absorption in 1846 of the Bristol and Gloucester Railway enabled the Midland to reach Bristol, the terminus at Temple Meads adjoining that of the Great Western. Because of certain legal engagements, the Bristol and Gloucester Railway was for a time obliged to remain a broad-gauge line, and it was not until 1854 that the narrow-gauge track was laid to Temple Meads. Here Kirtley also showed his foresight by building broad-gauge engines designed for ultimate conversion to the narrow gauge. He reduced the width of the axles, thus antedating by some forty years the convertible Great Western engines that were built when the abolition of the 7 ft. 0¼ in. gauge was definitely in sight. Two years before the Midland was able to work through on the narrow gauge to Bristol, a proposal had been put forward for amalgamation with the London and North Western. The latter company was agreeable, and the Midland was eager, since its constantly growing traffic was every year rendering direct access to London a question of greater urgency. But the scheme fell through, as the North Western, "thinking the bargain safe," insisted on knocking fifty shillings a share off the minimum price that had been fixed by the Midland chairman. Later in the same year the Midland company was approached by both the North Western and the Great Northern with a view to amalgamation, and the matter went so far as the promotion of a Bill in 1853 for the fusion of all three companies. Had this plan materialised, the result would not only have been the creation of the greatest single railway system under one ownership then in existence in any country, but might also have profoundly influenced British railway practice as a whole. Parliament considered that the national interest would be best served by the existence of as many competing railways as possible, and threw out the measure.

Had the scheme succeeded, it would have saved much competition that while it gave certain benefits to the public, inflicted considerable losses on the stockholders. It has been said that the Great Northern (now part of the London and North Eastern Railway) was "pre-eminently a fighting line" during the whole of the first twenty-five years of its life. Its inception was attended by a Parliamentary battle with the Midland that has no parallel in British railway history. In the year of the Great Exhibition the rivalry between the two companies brought the first-class return fare between Leeds and London down to five shillings. This bargain was nothing in comparison with the fare cutting of 1856, when the York London return fare was reduced to five shillings first-class and half a crown third-class, while from Peterborough to London and back passengers could book for as little as a shilling. Fifteen years later, the Midland and the Great Northern engaged in another war, during which coal was carried from the South Yorkshire pits to London at a third of the normal rates. Before leaving the Midland, we may recall two more historic facts of its career. It was the first railway to carry coal to London. In 1845 coal was conveyed from Clay Cross to Rugby, whence it was transferred to the London and Birmingham Railway, to the great disgust of the autocratic general manager of that system, who complained that his line would next be called on to carry manure. The traffic was accepted, but "it is on record that when coal trucks first passed over this line they were 'sheeted' down so that their contents might not be suspected; and at Weedon, where coal was transferred to the railway from the barges of the Grand Junction Canal, there stood for many years a high screen, erected originally to conceal the ignominious transaction from the eyes of the passing traveller." Today, coal and coke tonnage represent a far greater volume of traffic on the British railways than all other merchandise put together, and in 1934 the L.M.S. alone carried over seventy-two million tons, or more than half as much again as every other class of general freight and minerals.

The germ of the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway was the Manchester-Normanton-Leeds section of the Manchester and Leeds, which was opened on March 1, 1841, although it had been incorporated in 1836, and talked about for over ten years before then. In 1838 there was opened the Manchester and Bolton, which began life as a scheme for converting the Manchester, Bolton and Bury Navigation Canal into a railway; it was subsequently considered preferable to build a railway more or less parallel with the waterway. This line was amalgamated in 1846 with the Manchester and Leeds, and in the following year the two companies and five others, of which the Manchester and Leeds was the must important were fused into a new undertaking, the Lancashire and Yorkshire. Out of this amalgamation there grew a compact east-to-west system traversing the north of England from Goole to Liverpool. It serves a number of the most important industrial centres, such as Manchester, Wigan, Burnley, Oldham, Bradford, Huddersfield, Barnsley, Bury and Preston, and it had offshoots to the seaside resorts of Blackpool and Southport, and to the port of Fleetwood. This undertaking, which was joint owner of sixty-eight miles of line, in addition to the 533 miles of its own, was among the most important railway owners of docks and steamships. There was a long-standing friendly association with the London and North Western dating from 1862, and coaches in the Lancashire and Yorkshire livery were for many years a familiar sight at Euston. The two companies attempted to amalgamate in the 'seventies, and they succeeded just before the grouping of 1923.

The Lancashire and Yorkshire was a pioneer in electric traction, which was first introduced on the Liverpool-Southport-Crossens section in 1904, the year of the electrification of the North Eastern's Tyneside lines. These two companies were thus the first British mainline systems to replace steam by electrical working. Another Lancashire and Yorkshire innovation was the printed ticket. The inventor, Thomas Edmondson, first offered it to the Newcastle and Carlisle, which would have nothing to do with the newfangled idea, and then took it to the manager of the Manchester and Leeds, who "was just in the mood to jump at it," because of the delay at the booking-office windows" while the clerks wrote their fastest with spluttering quill pens and pencils that broke at the point." Edmondson's device was therefore given a trial on a section of line on his own modest terms of half a sovereign a mile of road a year. The invention was shortly after taken up by the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway, and became so popular that Edmondson was able to pay off his old bankruptcy creditors in full, and then to make a fortune for himself. The Furness and North Staffordshire Railway, both ranking as constituent companies, were much smaller concerns. The former originated in a line in the Barrow district that was mainly intended for the conveyance of minerals. It has been described as "a local line unconnected with the main railway system." This undertaking was incorporated in 1844. Subsequently the company absorbed the Ulverston and Lancaster, Coniston, and Whitehaven and Furness Junction Railway, took over the working of the Cleator and Workington Junction, and was the joint owner with the Midland and North Western of other lines. At grouping, it owned 115 miles of route, in addition to its share of twenty-four miles of joint railway. and the important Barrow Docks, to which no other railway system had direct access.

The North Staffordshire, which served the "Five Towns," was the larger and more important of the two minor constituent companies. Its northern extremity was Macclesfield, and by the exercise of running powers its trains ran also into Nottingham, Derby, Burton-on-Trent, Birmingham, Wolverhampton and Walsall, Wellington, on the Great Western, and Rugby, where the North Western station was its farthest south. The North Staffordshire was one of the systems whose history virtually began with amalgamation. In 1846 Parliamentary powers were obtained for the construction of three separate lines - the Churnet Valley, Harecastle and Sandbach and the "Potteries" Line. In the following year the three schemes were consolidated under the title of the North Staffordshire. Five other small undertakings were subsequently absorbed, and the company also worked the Leek and Manifold Railway, a line, now closed, eight miles long, on the 2 ft. 6 in. gauge. Immediately before grouping, the owned mileage amounted to 206. The company also had a share with the Great Central in the Marple and Bollington Railway, eleven miles in length. Mention must also be made of an undertaking that, although small in point of mileage, formed an important link in the British railway system. This was the North London Railway, which was incorporated in 1846 for the purpose of linking up the London Docks by a line from the North Western's Camden Town goods station. A close working arrangement always existed between the two railway companies, and the North London head offices were at Euston Station, where its stockholders' meetings also used to be held. At the end of 1908 an agreement was entered into under which the North London was thenceforth worked under the supervision of London and North Western officers, but the railway remained a separate undertaking until 1923.

The original grouping scheme provided for five and not four amalgamated companies, the intention having been to set up a separate group for Scotland. But the Scottish companies objected on the ground that the small population of the country and the relative lack of industrial development would impose a financial handicap on such a group, and that they therefore preferred to be associated with the English companies. The scheme was amended accordingly, the general basis being that the lines forming the Scottish section of the West Coast route became part of the L.M.S., while those on the East Coast went to the L.N.E.R. Including joint lines and small subsidiaries, the total route length of the Scottish lines taken over by the L.M.S. was approximately 2,200 miles. The largest system was that of the Caledonian Railway, with a route mileage of 896. It had the longest main line of all the Scottish companies, extending from Carlisle to Perth and Aberdeen, via Coatbridge, with offshoots to Edinburgh and Glasgow. Together with the London and North Western Railway, it formed the West Coast Route between England and Scotland.

The undertaking out of which this railway developed was incorporated in 1845, for the construction of a railway from Carlisle to Edinburgh and Glasgow, and the company did not obtain its Act of Parliament until after a fierce and lengthy struggle, which cost £70,000. Once powers had been obtained, the work proceeded so rapidly that the first sod was cut on October 11 of the same year, the initial section from Carlisle to Beattock was opened in September, 1847, and trains were running through to Edinburgh and Glasgow in the following February. The early history of the Caledonian was not peaceful. "Under powers of various Acts, this company, at a time of great excitement and much uncertainty as regards the real profits made out of railway undertakings, became involved in engagements which were found to be beyond its resources," and a financial rearrangement, which was carried out in 1851, consequently became necessary. When the company obtained its first Act there was a general belief that traffic possibilities would never warrant the construction of more than one trunk line between England and Scotland, and the railway history of the period is coloured by the fight between the advocates of the West Coast and East Coast routes. The Glasgow and South Western Railway was a more compact undertaking. It began at Gretna Junction, whence its trains ran the eight and a half miles to Carlisle over the Caledonian tracks, and the main line extended to Glasgow, via Dumfries and Kilmarnock. Another line ran along the west coast of Scotland, serving Ayr and Ardrossan, and connecting with the Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Railway, an east to west line in which the company had a joint share with no fewer than three other systems - the Caledonian, London and North Western and Midland. The Kilmarnock and Troon Railway, to which reference has already been made, formed part of the system, the total length of which, inclusive of its share of joint lines, amounted to 449 miles. Carlisle formed the southern terminus of both the Caledonian and Glasgow and South Western systems. Before 1923 the station was managed by the Carlisle Citadel Station Joint Committee, which had the status of a joint railway company, and it was jointly owned by the Caledonian and the London and North Western. Five other railways - the Midland, Glasgow and South Western, North Eastern, North British, and the little Maryport and Carlisle - made use of it as tenants. Thus no fewer than seven British railway companies used the same passenger station. Five of the seven are now absorbed in the L.M.S., which has become the sole proprietor of the station.

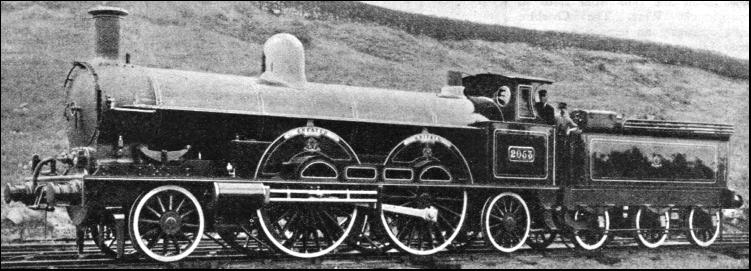

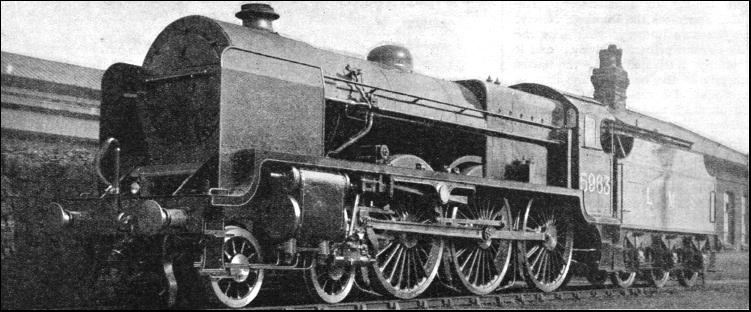

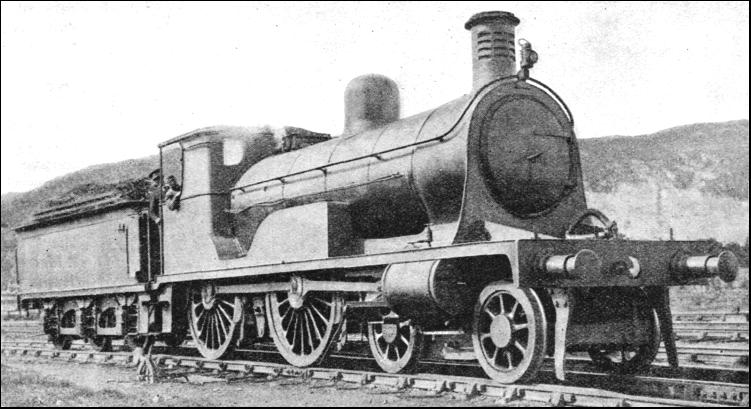

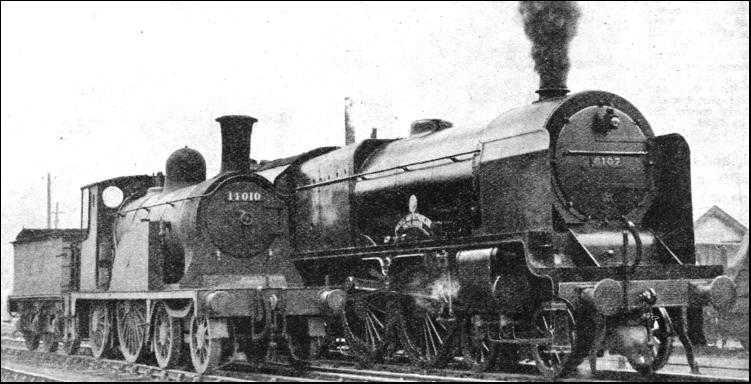

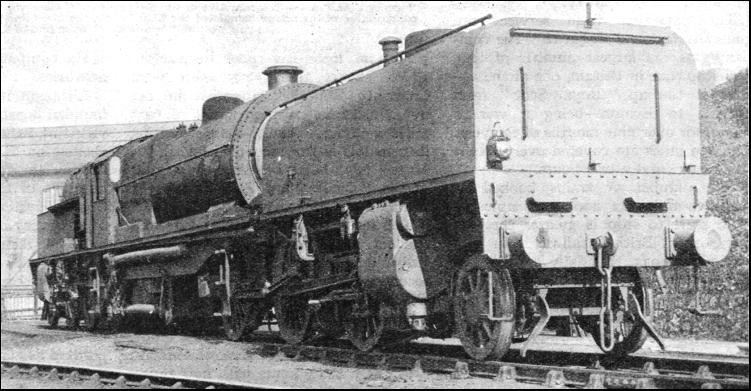

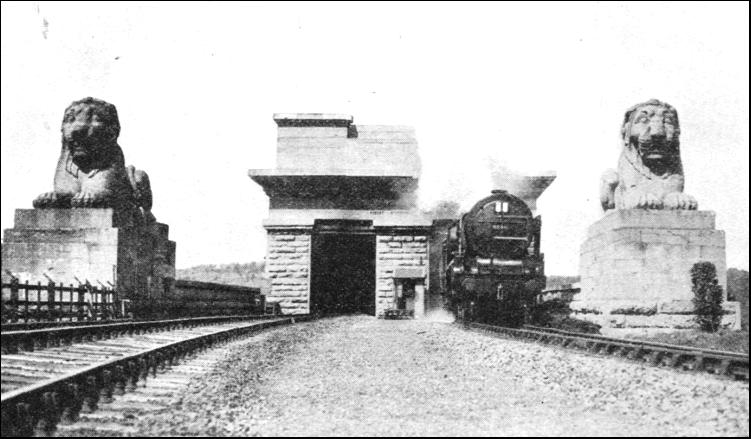

The Highland Railway, as its name implied, was an undertaking entirely confined to the north of Scotland, over which its line spread in the shape of a cross. The southern terminus was at Stanley Junction, near Perth, where it linked up with the Caledonian. It extended northwards to Wick and Thurso, and the centre of the system was Inverness, through which passed the lines to the east and west coasts. It began with the fifteen-miles Inverness and Nairn Railway, opened in 1855, which was three years later amalgamated with a line from Nairn to Keith. The total length before grouping was 485 miles, most of which was single track. Track troughs, which enable locomotives to take up water, were first laid in 1860. They were the invention of John Ramsbottom, a famous locomotive superintendent of the London and North Western Railway. Their use has permitted the introduction of the long non-stop runs which are a prominent feature of modern British railway working. Of the locomotive works, Crewe has been described as "probably the largest and most celebrated railway establishment in the world." It opened its doors in 1843, when it was owned by the Grand Junction Railway, and has an area of some 160 acres, of which over fifty are covered, In recent years it has undergone extensive modernisation. Second in point of importance on the L.M.S. are the Midland "shops" at Derby, which make carriages and wagons, as well as locomotives, and cover about 210 acres. The carriage "shops" on the Western Division are at Wolverton, Bucks. Famous engines of the nineteenth century, beginning with Stephenson's "Rocket," include the "Bloomers," "Precedents," and Webb compounds of the London and North Western, the Midland bogie singles and the Caledonian 4-4-0's. The twentieth century saw such successful classes as the North Western "George the Fifth" 4-4-0's and the Midland compounds. Modern L.M.S. locomotives include the "Princess Royals." the "Royal Scots." the "Baby Scots," and the Stanier two-cylinder and three-cylinder 4-6-0's. The latest L.M.S. freight engines are two-cylinder 2-8-0's, introduced in June, 1935. In the same month appeared a new 4-6-2 turbine-driven express locomotive, No. 6202.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |