|

|

THE West Side line of the New York Central Railroad Company does not carry passengers, and no high-speed expresses flash along the track ; yet it is known as the "Lifeline of New York," because the city, to a considerable extent, depends upon this route for its food and milk. The line is used also for fast goods traffic. It is the only all-rail goods line on Manhattan Island, on which the centre of New York City is built. In recent years a project called the West Side Improvement, a scheme so gigantic and intricate as to be one of the greatest ever undertaken jointly by public and private interests on Manhattan Island, has been partly completed. One feature ot the scheme is that factories and warehouses are being built over the track. The trains are operated by electricity and by Diesel-electric locomotives, so that there is no smoke problem to concern the authorities. The importance of the scheme can be realized from the fact that, since the nucleus of New York is on Manhattan Island, the transport problem is different from that of London, Paris, Berlin, and other big cities. Moreover, Greater New York now claims to be the largest city in the world, having won that distinction from Greater London in the last census with a population of 10,901,424, as against London's 8,202,818. It is also the principal seaport of America. Over its wharves pass forty-three per cent of all the foreign commerce of the United States, including that via the Pacific coast and Canadian and Mexican borders. Of this vast traffic the New York Central Railroad alone handles one-fourth over its own piers or on its fleet of 334 harbour craft. The transport problem is therefore very complicated. At a conference of various committees an official of the Port of New York referred to plans for replacing the method of carrying goods round the harbour in vessels by substituting a belt of railway lines. There are about 800 miles of water front, about a quarter of which is developed, with some 700 piers, from which, on an average, steamers sail every twenty minutes during the day. The freight carried by tlie vessels at this time amounted to 120,000 tons a day, but that handled by the railways serving the port was far greater, being 200,000 tons a day. Some of the chief difficulties of handling commerce were due to the fact that, of the twelve major railways, most had terminals on the west side of the Hudson River, and were separated from the thickly populated eastern side by wide and deep waterways.

The New York Central is fortunate. Through its West Shore Railroad it has extensive terminals on the west bank of the Hudson River at Weehawken, New Jersey, and at Hoboken and Jersey City, farther clown, including wharves at which steamships may unload direct from railway wagons. Because of its exceptional position on either side of the Hudson River the railway carries a quarter of all the freight between the metropolitan district and Buffalo and places west, and a third of all the freight between Manhattan Island and the west. No less than forty-five per cent of the milk and cream for the city is delivered by the company. When New York was a city of moderate size on the lower end of Manhattan Island a goods station was built at St. John's Park, which was then on the outskirts of the city, by the old Hudson River Railroad, now a part of the New York Central. The name of St. John's Park, unusual for a goods station in the United States, was due to the fact that the station was on the site of a park once owned by St. John's Episcopal Church. This old landmark on the east side of Varick Street was destroyed by the construction of the West Side Subway. The goods station was opened in 1868 on Hudson Street between Laight and Beech Streets. As the city grew, the goods station, instead of being on the outskirts, became the heart of the wholesale dry goods and grocery districts. It was also very near the upper limits of the financial district. Each year it saved merchants thousands of pounds in trucking charges. Additional goods stations were opened at Thirty-third Street, then at Sixtieth Street and at One Hundred and Thirtieth Street. These city terminals soon proved their value, as they were always available when bad weather impeded, or stopped entirely, the navigation of New York Harbour and the Hudson River by car floats and lighters—the only other means of receiving and sending railway goods. At such times the West Side Line was practically the sole artery along which food and fuel was conveyed to New York's millions. But the growth was such that developments were required. Planning and negotiations went on at intervals for more than forty years between the company and the city and various interests, until at last it was agreed to abandon the old line and replace it by a new one. Situated as the line was, the transactions incidental to securing the title to the right of way to the improvement involved about 350 separate deals in nearly sixty blocks, from Spring Street to Sixtieth Street Yard, and the whole formed one of the most extensive property deals ever undertaken by private interests in New York City. The company began work in 1925, and in June, 1934, the new St. John's Freight Terminal was formed and tlie completion of tlie scheme came within sight. It alters a number of things. Railway crossings at 105 streets are eliminated, and the track is removed from several important thoroughfares running north and south, freeing these avenues and streets from the congestion and traffic troubles inevitable when goods trains are running. It also means the discontinuance of steam locomotives in the city, as the electric third-rail system is extended south to Thirtieth Street. Main line trains south of this are shunted in the Thirtieth and Sixtieth Street Yards. For industries south of Sixtieth Street the traffic will be handled by thirty-six Diesel-electric locomotives.

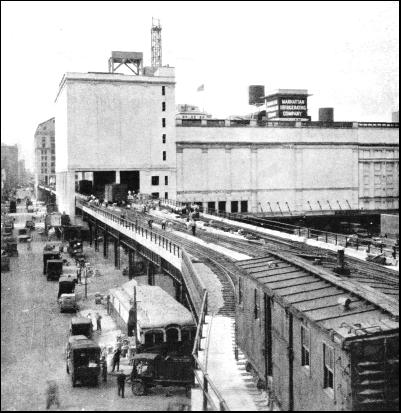

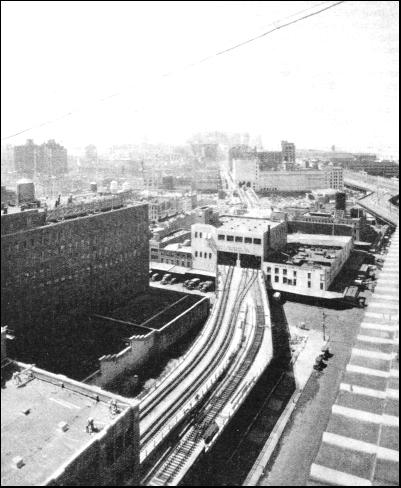

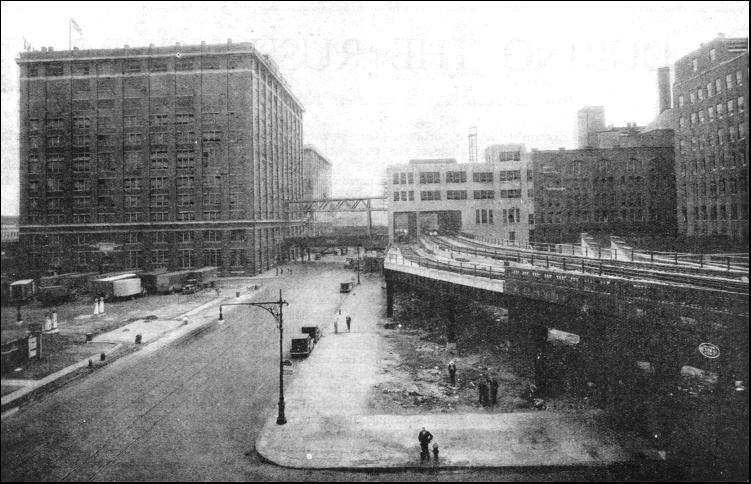

Another outcome is the development of Riverside Park, the covering of the railway north of Seventy-second Street with an express motor highway, and easy access to thirty-two acres of additional recreation space for the public. The improvement of the goods handling and shunting services on the new right of way aids the development of this important industrial area without interfering with street traffic. The old terminal was abandoned and a new one was built at the southern terminus of the new line at Spring Street. The name, St. John's Park, had become so well known that it is continued as the name for the new station. Trains are operated from the new station on a two-track elevated structure along a private right of way to Thirtieth Street Yard, crossing about forty intersecting streets on overhead bridges. The Thirtieth Street Yard is between Thirtieth and Thirty-seventh streets and the area is ten blocks. This goods yard and also that at Sixtieth Street—which is double the size and is between Fifty-ninth and Seventy-ninth Streets—will be rearranged and improved. The tracks between the two yards are to be on a private right of way between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, and are to be built below the street level and will be carried under the cross-streets. Both the yards, which are among the largest privately owned areas in New York City, will be reconstructed so that in the future they can be covered by large commercial buildings, none of the valuable overhead space being wasted. Above Seventy-second Street the railway follows the old gradient and line, but it will be covered by a steel and concrete roof, thus providing for the motor express highway and making possible the extension of Riverside Park down to the water front. To make room for the new line a total of 640 buildings, including a church and two schools, were removed. The section of the line which is carried below the street level, as well as the elevated part, is expected to be covered and built over with warehouses and factories. The outstanding feature of the entire scheme is the new St. John's Park Station. When ultimately completed it will occupy four blocks between Spring, Clarkson, Washington, and West Streets. The initial building covers the northern two-thirds of the area extending from the south side of Charlton Street to Clarkson Street, and is about 800 ft. long. With its three stories and basement it has a gross floor area of 730,000 sq. ft., and is served by eight tracks having a standing capacity of 150 wagons. The completed terminal is planned to cover all four blocks and to be twelve stories high, 1,260 ft long, and with a width varying from 190 to 282 ft. The gross floor area will be 3,500,000 sq. ft. Eight railway tracks witli a standing capacity of 193 wagons will serve the building. The terminal is of steel and concrete construction ; the exterior is of light buff brick with Indiana limestone trim and a base course of granite, the doors and windows being of steel. The whole stands on 311 caissons that were carried 60 to 90 ft. down to bed-rock. The first floor, which is at street level, is the freight house and has platform space for 127 trucks inside the building. The whole of this floor, including these truck-pockets, is enclosed by steel doors, which are operated by motors, along the building line. The second floor is the track floor and has eight tracks in pits with a concrete track floor construction to facilitate cleaning. The track platforms are built with recesses in the edge to enable container cars to be handled. Perishable goods that are being held over are stored in the two refrigerator rooms that are on this floor. The third floor has goods office and record storage facilities, and also arrangements for servicing electric trucks. The roof of the building is designed as a future fourth floor, and the columns have been built to carry nine additional stories. To carry goods between the street floor and the track floor there are fourteen lifts, two of which are large enough to hold trucks. The offices on the third floor are connected with the platforms on the street and track floors by a system of pneumatic tubes. A five-ton hoist is provided at the south end of the building to shift heavy and bulky cases or articles direct from cars on the second floor to trucks in the service drive-way on the street level. The building is equipped with sprinklers, and is one of the most completely fire-proofed buildings in New York City.

Freight can be handled in both carload and less than carload quantities. As St. John's Park has been the city's chief delivery station for dairy produce for more than half a century the facilities for dealing with butter, eggs, cheese and dressed poultry are adequate. The Customs Service has offices in the building, and a corps of inspectors to attend to goods arriving in bond, which are cleared quickly, and promptly forwarded. Leaving the station and going north, the two main tracks of the line are carried on a viaduct up to Thirtieth Street. Here the line turns west and encircles the goods yard to have sufficient space to overcome the difference in levels between the viaduct and the tracks below street level which are to the north. Provision for building future industrial tracks has been made, and sidings now under construction will afford direct service to many industries. The construction of the viaduct was one of the most difficult problems of the scheme, from an engineering point of view. It is of steel with concrete floor construction, the tracks being carried on stone ballast, except in the packing house district between Little West Twelfth and West Fourteenth Streets, where they are on concrete. The "air rights," that is, the rights of erecting warehouses and factories over the track, are being developed. These new buildings will have direct access to the track by means of sidings. In this way raw materials will be brought into a building by rail, and manufactured on the premises above the track. The finished articles will then be placed in wagons on the sidings so that road haulage is avoided. The saving in having a railway on the premises is expected to lower the cost of manufacture. Most of the work in the initial programme has been completed north of West Seventy-second Street, except for the elimination of the crossings at West Seventy-ninth and West Ninety-sixth Streets by carrying the streets over the tracks. In the Manhattanville district the line has been elevated, crossing over the streets between St. Clair Place and West One Hundred and Thirty-fifth Street by a three-track viaduct. Side-tracks have been provided on this high level to serve a number of packing houses. With train operation on the new viaduct there disappeared one of the picturesque scenes of New York City, the boys on horseback, who under an old by-law had to ride ahead of each locomotive or train passing through the street. These West Side "cowboys" and their predecessors, each carrying a red flag giving warning of the approach, at six miles an hour, of the train he preceded, had been riding up and down the West Side of Manhattan since 1849. When the full programme of improvement is completed throughout, the line will be thirteen miles in length.

Many thanks for your help

|

Share this page on Facebook - Share  [email protected] |