Civil War Field Fortifications

Lines with

Intervals

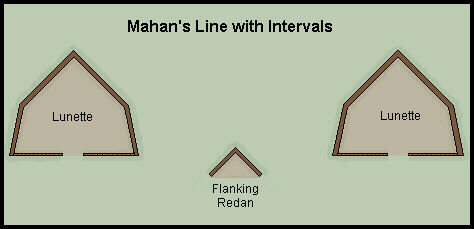

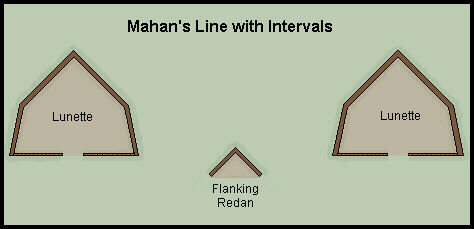

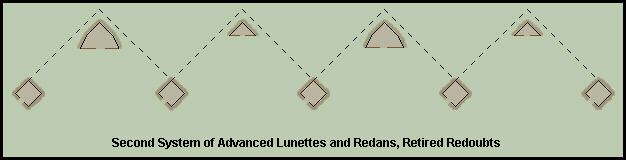

Nineteenth century manuals describe at least three distinct

systems for arranging field works within lines with intervals. D. H. Mahan

offered a system composed of three distinct lines of works in his Complete

Treatise on Field Fortifications. Mahan's first line was composed of

lunettes or square redoubts with salient angles 250 yards apart. Each

lunette, which Mahan preferred over redoubts because they were open at the

gorge and their interiors were subject to fire from the second line, was

to be large enough to conveniently shelter a garrison of 300 to 400 men and

a field battery and have 90 degree salient angles with faces about

60 yards and flanks 40 yards long. Each lunette was to be positioned to project

columns of fire well across the fronts of the salient angles of collateral

lunettes. The gorge of each lunette was to be obstructed with abatis or

palisading to prevent the enemy from gaining easy access to the

rear of the

work. The size of Mahan's prescribed garrisons for the works of the first

line suggests that each lunette was to have its own reserve and be able to

defend itself independent of the other works in the line. The second line

was composed of redans with faces about 40 yards long which were positioned

to cover the intervals between works of the first line with the faces directed

to project their columns of fire across the faces of the lunettes of the

first line. Second line redans were to include an armament of artillery

to increase the strength of supporting fire for the first line. In positions

where cavalry could be used to advantage a third line consisting of large

epaulments could be constructed 200 yards in rear of the salients of the

first line to protect the cavalry from enemy fire while they awaited orders

to advance with the reserve to counter the enemy. These works were only intended

for the protection of cavalry and were not prepared for defense with banquettes

or artillery platforms.

rear of the

work. The size of Mahan's prescribed garrisons for the works of the first

line suggests that each lunette was to have its own reserve and be able to

defend itself independent of the other works in the line. The second line

was composed of redans with faces about 40 yards long which were positioned

to cover the intervals between works of the first line with the faces directed

to project their columns of fire across the faces of the lunettes of the

first line. Second line redans were to include an armament of artillery

to increase the strength of supporting fire for the first line. In positions

where cavalry could be used to advantage a third line consisting of large

epaulments could be constructed 200 yards in rear of the salients of the

first line to protect the cavalry from enemy fire while they awaited orders

to advance with the reserve to counter the enemy. These works were only intended

for the protection of cavalry and were not prepared for defense with banquettes

or artillery platforms.

The two most notable features of Mahan's line were the

strength of its artillery armament and the inability of guns mounted in the

retired redans to reach the interiors of the advanced lunettes with their

fire. Given field batteries of six guns in each advanced lunette arranged

with three guns firing from each face and at least two guns on each face

of the retired redans, the space between collateral lunettes, 250 yards wide,

would be covered by ten field guns and howitzers. This concentration of artillery

within a limit area indicates that the lunettes and redans were primarily

intended as artillery positions which could be protected from close assault

by their infantry garrisons. Not only would the artillery provide the

strongest part of the defensive fire delivered from the works, their fire

could also support troops advancing through the intervals to attack the enemy.

Mahan's system arranged the retired redan in a manner that prevented

their artillery armament from gaining a direct fire into the interior spaces

of the advanced lunettes. The redans were placed too close to the line of

the gorges of the advanced lunettes and their faces did not extend far enough

to the rear to overlap the flanks of the lunettes. An enemy force, having

capture a lunette, would be protected from the redans' fire by the 40 yard

length of the lunettes' flanks. Reserve batteries that were not tied to the

defense of the works would have to be moved into position to fire into the

the lunettes in order to make them untenable for the enemy.

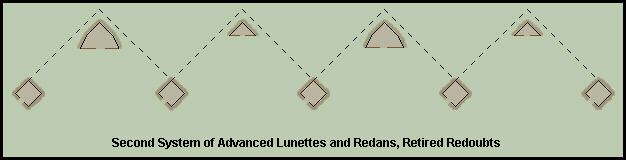

Another system ,described in H. L. Scott's Military

Dictionary, called for an advanced line of works open at the gorge (lunettes

or redans) supported by a second line of irregular shaped redoubts 400 to

500 yards to the rear and positioned to cover the intervals in the first

line. Collateral works were to be within range of each other, between 600

and 700 yards apart, and each was to be capable of an independent defense.

Unlike Mahan's system, there was no prescribed form for the redoubts of the

second line, rather, they were to be adapted to the terrain and capable of

sustaining a strong defensive effort in all directions with their parapets

defiladed by directing the lines of the interior crests toward ground

inaccessible to the enemy.

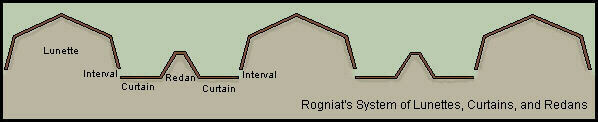

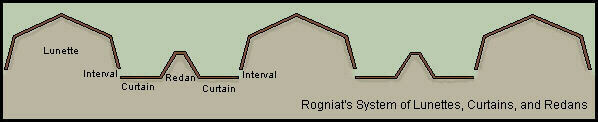

A third system, described and popularized by D. H. Mahan,

had been developed by French General Rogniat which called for a series of

large lunettes of low profile flanked by small redans and straight curtains.

The capitals of the large lunettes were spaced 250 yards apart with faces

60 yards and flanks 40 yards long. A straight curtain overlapped the flanks

of collateral redans and was broken in the center by a small redan with a

pan-coupe which was positioned to provide flanking fire across the ground

in front of the lunettes' faces. An interval about 10 yards wide was left

between the terminus of the lunettes' flanks and the front of the curtains'

flanks. The lunettes were to be given a profile that included parapets about

five feet thick arranged for defense by infantry and ditches no more than

6 feet deep and 12 feet wide. The curtains were formed from an interior trench

with earth thrown in front to form a parapet about four feet high and arranged

with steps to allow infantry to easily mount the parapet from the interior

of the work. Each redan was constructed as a barbette

battery for

field artillery with a low parapet two feet, six inches tall and a ditch

in front only deep enough to provide the earth for the parapet.

for

field artillery with a low parapet two feet, six inches tall and a ditch

in front only deep enough to provide the earth for the parapet.

Rogniat's system offered a sound method for protecting

an army's front with a nearly continuous line of field works while providing

the means for troops to pass over low parapets or through intervals

between the works in order of battle to counter attack the enemy. While

infantry were to advance over the curtains cavalry and light artillery were

to pass through the small intervals between the lunettes and curtains.

Since the advance started from the retired portions of the line the

first troops over the curtains' parapets would benefit from the protection

of troops defending the advanced lunettes. Mahan also believed that the retired

artillery redans would naturally draw the attacking army's artillery fire

away from the more exposed lunettes as the attackers' guns tried to support

the attack by silencing defending batteries. The system , in short, worked

as a regular line with intervals without wide intervals while providing better

cover for the defending army's troops and artillery. Just as important, the

low profile of Rogniat's works meant that they could be constructed relatively

quickly by an army that had all ready assumed its position and order of battle.

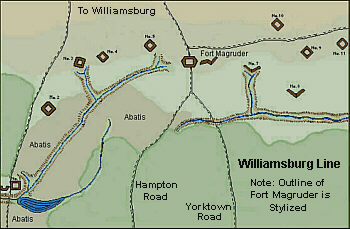

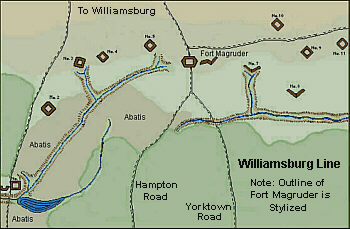

The Williamsburg Line was originally intended as a secondary

position to block the egress of an enemy army from the Yorktown Peninsula.

The redoubts were arranged for reciprocal defense with their faces projecting

columns of fire across the salient angles of collateral works. Two small

advanced redans guarded ravines that might otherwise have been used by an

enemy to approach the line undercover. The interior spaces of the redans

were seen from the main line of redoubts and exposed to their fire. The redoubts

were relatively far apart and seem primarily to have been intended as battery

positions. During the Battle of Williamsburg the redoubts and Fort Magruder

served as battery positions when the Confederate infantry advanced through

the line to attack the advancing Federal army.

The interior line of defense guarding the southern approaches

to Savannah, Georgia contained an interesting combination of linear forms.

Part of the line was composed of 18 detached lunettes and three redans. Most

of the works were prepared for an artillery armament of one gun mounted en

barbette at the salient angles. The lunettes had a relatively strong

profile and the salients were an (estimated) average of about 250 yards apart.

It is not clear why the engineer who designed the interior line chose to

employ a line of detached works, especially since the number of troops available

to defend the line was far too limited to allow the Confederates to risk

a counter attacking defense

The lines of defense for James Island, the primary southern

approach to Charleston Harbor, were established in principle prior to the

time when Major General J. C. Pemberton assumed command of the Department

of South Carolina and Georgia (March 14, 1862) and were positioned with regard

to the Federal Navy's command of the waters exterior the harbor and its presumed

ability to penetrate at will into unprotected coastal waterways.The

Stono River, which formed the southern boundary of James Island, was wide

and deep enough to allow passage of small Federal gunboats and transports.

Unable to amass a sufficient number of heavy guns to both protect the entrance

to Charleston Harbor and block the Stono River, the Confederates chose to

surrender passage of the Stono and establish their line of defense on James

Island at a distance from the river to repel an overland attack. The

line was divided into two sections, the West Line, which connected to the

landside defenses of Charleston, was constructed as a continuous line of

redans which ran from the Wappoo River to the Swamps of James Island Creek.

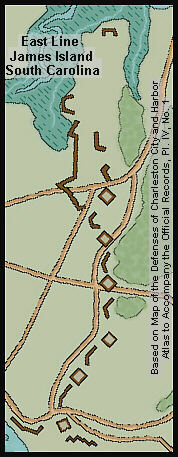

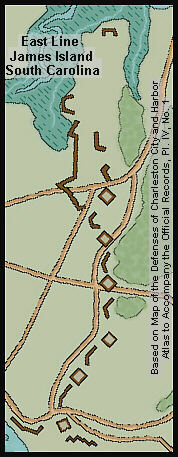

The East Line on James Island conformed to the second system

discussed above. A line of redoubts of strong profile and well armed with

artillery was positioned between the swamps extending from Light House Creek

on the east to James Island Creek to the west. The redoubts were arranged

for reciprocal defense and the artillery armament was positioned at the redoubts'

salient angles. Intervals between the redoubts were covered by a line of

advanced redans the interior spaces of which were seen and exposed to fire

from the redoubts. A line of low rifle pits was placed well in front of the

redans covering the right front of the line. Lines with intervals assumed

that the defenders would have a sufficiently large number of troops to be

able to counter attack an enemy army attempting to force its way through

the line. When the East Line was constructed, the garrison at Charleston

was large enough for a counter attacking land defense, but as troops were

withdrawn and sent to other theaters of action and the size of the garrison

decreased, the East Line began to require an inappropriately large number

of troops to both man the works and provide a strong reserve.

When Major General P. G. T. Beauregard assumed command

of the Department the land defenses of James Island were considered defective

in several important respects. The East and West lines gave up too much ground

on the island and required too many troops to hold adequately defend them.

The East Line was criticized as poorly located and designed since the redans

were thought to block artillery fire from the redoubts. The rifle pits in

front of the right section of the line were thought to be poorly placed since

they would prevent artillery in the retired works from reaching beyond the

line. All of the works were constructed with profiles that were far to strong

to allow infantry to pass over them with ease. Alfred Roman, who served on

Beauregard's staff and mentioned these criticisms in his massive missive

The Military Operations of General Beauregard basically regarded the

East Line as defective because it did not follow Roginat's system. Whether

Roman, an ordnance officer, understood the objective of the system used to

design and construct the East Line is not clear, but certainly the line was

severely weakened by the withdrawal of troops from the Charleston garrison

and the Federal army's decision to limited their operations to Morris Island

and closing the harbor entrance rather than attempting to strike at Charleston

by way of the Stono. The later Federal decision allowed the Confederates

to replace the East and West lines on James Island with a new line farther

forward that had its left anchored on Fort Lamar and the swamps around Light

House Creek.

Back to Major Works

Redan Lines

Tenaille Lines

Cremaillere Lines

Bastion Lines

Contents Home

Page Minor Works

Siege Works

Permanent Fortifications

Glossary

Copyright (c) PEMcDuffie 1998

rear of the

work. The size of Mahan's prescribed garrisons for the works of the first

line suggests that each lunette was to have its own reserve and be able to

defend itself independent of the other works in the line. The second line

was composed of redans with faces about 40 yards long which were positioned

to cover the intervals between works of the first line with the faces directed

to project their columns of fire across the faces of the lunettes of the

first line. Second line redans were to include an armament of artillery

to increase the strength of supporting fire for the first line. In positions

where cavalry could be used to advantage a third line consisting of large

epaulments could be constructed 200 yards in rear of the salients of the

first line to protect the cavalry from enemy fire while they awaited orders

to advance with the reserve to counter the enemy. These works were only intended

for the protection of cavalry and were not prepared for defense with banquettes

or artillery platforms.

rear of the

work. The size of Mahan's prescribed garrisons for the works of the first

line suggests that each lunette was to have its own reserve and be able to

defend itself independent of the other works in the line. The second line

was composed of redans with faces about 40 yards long which were positioned

to cover the intervals between works of the first line with the faces directed

to project their columns of fire across the faces of the lunettes of the

first line. Second line redans were to include an armament of artillery

to increase the strength of supporting fire for the first line. In positions

where cavalry could be used to advantage a third line consisting of large

epaulments could be constructed 200 yards in rear of the salients of the

first line to protect the cavalry from enemy fire while they awaited orders

to advance with the reserve to counter the enemy. These works were only intended

for the protection of cavalry and were not prepared for defense with banquettes

or artillery platforms.

for

field artillery with a low parapet two feet, six inches tall and a ditch

in front only deep enough to provide the earth for the parapet.

for

field artillery with a low parapet two feet, six inches tall and a ditch

in front only deep enough to provide the earth for the parapet.