Civil War Field Fortifications

Tenaille Lines

Tenaille lines were developed from standard redan lines

by eliminating the curtains between the redans and substituting alternating

large and small redans that were joined directly at their flanks. Where

standard redan lines were ill adapted for reciprocal defense, tenaille lines

allowed a very effective reciprocal defense between collateral redans. The

faces of the small redans were positioned perpendicular to the faces of the

large redans to allow their columns of fire to flank the ditches of the large

redans while crossing within the large redans' sectors without fire. The

small redans were in turn protected by by fire from the faces of the large

redans and were partially covered from direct attack by their retired position

between the large redans.

D. H. Mahan described two arrangements for redans

composing tenaille lines in his A Complete Treatise on Field

Fortification. The first arrangement envisioned large redans that had

60 degree salient angles, faces 160 yards long and a capital 138 yards long

measured from the salient to the line of the gorge. The distance between

capitals of the large redans was 228 yards. Intervening small redans were

to have faces no more than 40 yards in length and very obtuse (about 120

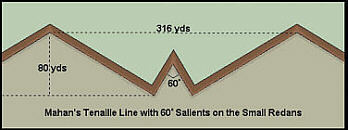

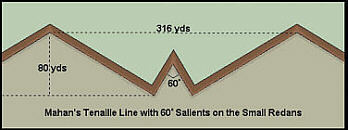

degree) salient angles. Mahan's second arrangement gave the small redans

60 degree salient angles, which produced very obtuse salients on the large

redans in order to bring their faces perpendicular to the faces of the small

redans. Capitals of the large redans were separated by a distance of 316

yards and each capital was 80 yards long. Each face was still 160 yards long.

Astute observers will have noticed that the large redans in both of Mahan's

tenaille forms were based on 30-60-90 right triangles. The first arrangement

joined two 30-60-90 right triangles to form an

D. H. Mahan described two arrangements for redans

composing tenaille lines in his A Complete Treatise on Field

Fortification. The first arrangement envisioned large redans that had

60 degree salient angles, faces 160 yards long and a capital 138 yards long

measured from the salient to the line of the gorge. The distance between

capitals of the large redans was 228 yards. Intervening small redans were

to have faces no more than 40 yards in length and very obtuse (about 120

degree) salient angles. Mahan's second arrangement gave the small redans

60 degree salient angles, which produced very obtuse salients on the large

redans in order to bring their faces perpendicular to the faces of the small

redans. Capitals of the large redans were separated by a distance of 316

yards and each capital was 80 yards long. Each face was still 160 yards long.

Astute observers will have noticed that the large redans in both of Mahan's

tenaille forms were based on 30-60-90 right triangles. The first arrangement

joined two 30-60-90 right triangles to form an

equilateral

triangle while the second arrangement joined the right triangles with the

short legs as the capital and positioned the longest legs to form the gorge.

The shear geometrical uniformity of Mahan's forms made them difficult,

if not specifically impossible, to apply in practice and even Mahan warned

that these forms were not to be restricted to the limits imposed by his

description of them.

equilateral

triangle while the second arrangement joined the right triangles with the

short legs as the capital and positioned the longest legs to form the gorge.

The shear geometrical uniformity of Mahan's forms made them difficult,

if not specifically impossible, to apply in practice and even Mahan warned

that these forms were not to be restricted to the limits imposed by his

description of them.

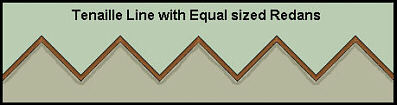

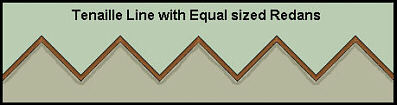

A third form for tenaille lines, which was not discussed

by Mahan, reduced all of a line's redans to the same size and gave them 90

degree re-entering angles at the joints between redans. The redans were based

on isosceles right triangles with 90 degree salient angles. This produced

a refined repeating zig-zag pattern with columns of fire from the faces that

provided

even better protection for the salient angles than Mahan's

arrangements since the entire length of each redan's face crossed its column

of fire in front of collateral redans' salient angles. As with Mahan's

forms this type of tenaille line had a geometric beauty and orderliness that

was almost impossible to translate into concrete structural form on uneven

ground.

even better protection for the salient angles than Mahan's

arrangements since the entire length of each redan's face crossed its column

of fire in front of collateral redans' salient angles. As with Mahan's

forms this type of tenaille line had a geometric beauty and orderliness that

was almost impossible to translate into concrete structural form on uneven

ground.

All three types of tenaille lines suffered from serious

defects that limited their use and compelled rather extreme modifications

in practice that for all intents and purposes negated the few advantages

this form of line had over other types of lines. Mahan's alternating large

and small redans pushed the large redans forward which made their faces very

vulnerable to distant enfilading artillery fire. A battery positioned

perpendicular to and on a prolongation of the line of the interior crest

of one of the large redans' faces could enfilade the entire 160 yard length

of the parapet. The only way to correct this problem would have involved

the construction of a series of traverses along each face. This solution

would have added an unreasonable amount of time and labor just to make the

line adequately defensible.

Although tenaille lines were, theoretically, superior to

standard redan and cremaillere lines because their arrangements for reciprocal

defense were more complete, they gained that superiority at the expense of

sound economy. Tenaille lines

required more linear yards of parapet and ditch to fortify

a given position than any other type of line. This also meant that tenaille

lines required more troops to man the parapet than other forms. The large

redans of Mahan's first arrangement, for example, required 320 yards of parapet

to fortify a position that was only 160 yards wide. Given the idea that a

good defense required at least one man per yard of parapet, 320 men would

have been required to defend each redan. By comparison a standard cremaillere

line on a front 160 yards wide required about 190 linear yards of parapet

and the same number of men to adequately defend it. Assuming that an army

taking up a position behind a continuous line did so in an attempt to match

its opponent's numerical superiority with field fortifications, the

fewer men necessary to defend a given section of front, the better chance

its would have been to counterbalance the enemy's advantage. The extra 130

men necessary for each redan in a tenaille line would have been better used

to create a strong reserve. Tenaille lines required too many men and too

much labor compared to other types of lines to have any practical use in

the field.

required more linear yards of parapet and ditch to fortify

a given position than any other type of line. This also meant that tenaille

lines required more troops to man the parapet than other forms. The large

redans of Mahan's first arrangement, for example, required 320 yards of parapet

to fortify a position that was only 160 yards wide. Given the idea that a

good defense required at least one man per yard of parapet, 320 men would

have been required to defend each redan. By comparison a standard cremaillere

line on a front 160 yards wide required about 190 linear yards of parapet

and the same number of men to adequately defend it. Assuming that an army

taking up a position behind a continuous line did so in an attempt to match

its opponent's numerical superiority with field fortifications, the

fewer men necessary to defend a given section of front, the better chance

its would have been to counterbalance the enemy's advantage. The extra 130

men necessary for each redan in a tenaille line would have been better used

to create a strong reserve. Tenaille lines required too many men and too

much labor compared to other types of lines to have any practical use in

the field.

Although standard tenaille lines were impractical for complete

continuous lines, they were used in modified forms during

the Civil War.

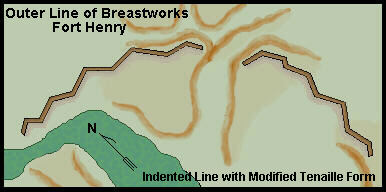

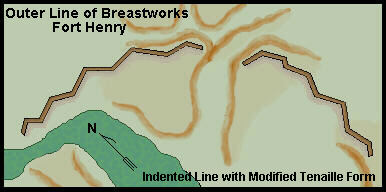

At Fort Henry on the Tennessee River the Confederates constructed a line

of "rifle pits" (which actually had the profile of breastworks) that employed

a series of repeating redans joined at the flanks as outworks to cover the

north and northeast land approaches to the main fort on the river bank. The

general form given the line resembled the third equal sized redan arrangement,

but in this case the redans' salients were mashed in and given very obtuse

angles and the faces did not join to form 90 degree re-entering angles. Though

the faces crossed their columns of fire at a distance, the angles used did

not allow reciprocal defense for collateral redans which negated the one

important advantage that the tenaille form had over other types of lines.

The repeating angular form given the line at Fort Henry seems to have been

intended solely as a means of breaking the continuity of the parapet and

preventing the entire length of the line from being enfiladed by distant

artillery fire.

the Civil War.

At Fort Henry on the Tennessee River the Confederates constructed a line

of "rifle pits" (which actually had the profile of breastworks) that employed

a series of repeating redans joined at the flanks as outworks to cover the

north and northeast land approaches to the main fort on the river bank. The

general form given the line resembled the third equal sized redan arrangement,

but in this case the redans' salients were mashed in and given very obtuse

angles and the faces did not join to form 90 degree re-entering angles. Though

the faces crossed their columns of fire at a distance, the angles used did

not allow reciprocal defense for collateral redans which negated the one

important advantage that the tenaille form had over other types of lines.

The repeating angular form given the line at Fort Henry seems to have been

intended solely as a means of breaking the continuity of the parapet and

preventing the entire length of the line from being enfiladed by distant

artillery fire.

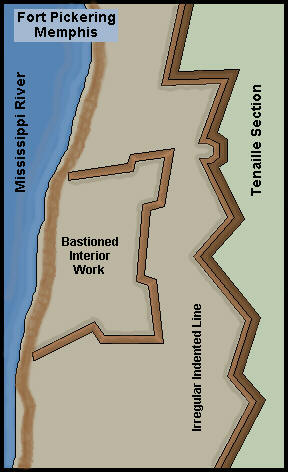

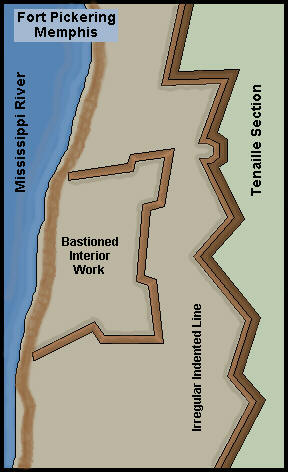

The main line of works composing the exterior defenses

of Fort Pickering, at Memphis, Tennessee, was given the general form of an

irregular indented line. One section of the exterior line was given a tenaille

form that resembled Mahan's second arrangement for small redans with 60 degree

salient angles. A small lunette designed with two flanks, two faces and a

substantial pan-coupe was positioned between two long faces which angled

forward to force the lunette into a retired position in the line. The long

face to the north of the lunette joined another face to form a sharp salient

angle. The collateral face to the south formed an obtuse salient angle which

strongly resembled a redan. The limited and non-standard tenaille trace used

at Fort Pickering was more typical of the use Civil War engineers made of

the tenaille form: it was limited in extent, only composed a section of a

longer irregular line, and was heavily modified to suit the fortification

requirements of the site.

Back to Lines

Redan Lines

Cremaillere Lines

Bastion Lines

Lines with Intervals

Contents Home

Page Minor Works

Siege Works

Permanent Fortifications

Glossary

Copyright (c) PEMcDuffie 1998

D. H. Mahan described two arrangements for redans

composing tenaille lines in his A Complete Treatise on Field

Fortification. The first arrangement envisioned large redans that had

60 degree salient angles, faces 160 yards long and a capital 138 yards long

measured from the salient to the line of the gorge. The distance between

capitals of the large redans was 228 yards. Intervening small redans were

to have faces no more than 40 yards in length and very obtuse (about 120

degree) salient angles. Mahan's second arrangement gave the small redans

60 degree salient angles, which produced very obtuse salients on the large

redans in order to bring their faces perpendicular to the faces of the small

redans. Capitals of the large redans were separated by a distance of 316

yards and each capital was 80 yards long. Each face was still 160 yards long.

Astute observers will have noticed that the large redans in both of Mahan's

tenaille forms were based on 30-60-90 right triangles. The first arrangement

joined two 30-60-90 right triangles to form an

D. H. Mahan described two arrangements for redans

composing tenaille lines in his A Complete Treatise on Field

Fortification. The first arrangement envisioned large redans that had

60 degree salient angles, faces 160 yards long and a capital 138 yards long

measured from the salient to the line of the gorge. The distance between

capitals of the large redans was 228 yards. Intervening small redans were

to have faces no more than 40 yards in length and very obtuse (about 120

degree) salient angles. Mahan's second arrangement gave the small redans

60 degree salient angles, which produced very obtuse salients on the large

redans in order to bring their faces perpendicular to the faces of the small

redans. Capitals of the large redans were separated by a distance of 316

yards and each capital was 80 yards long. Each face was still 160 yards long.

Astute observers will have noticed that the large redans in both of Mahan's

tenaille forms were based on 30-60-90 right triangles. The first arrangement

joined two 30-60-90 right triangles to form an

equilateral

triangle while the second arrangement joined the right triangles with the

short legs as the capital and positioned the longest legs to form the gorge.

The shear geometrical uniformity of Mahan's forms made them difficult,

if not specifically impossible, to apply in practice and even Mahan warned

that these forms were not to be restricted to the limits imposed by his

description of them.

equilateral

triangle while the second arrangement joined the right triangles with the

short legs as the capital and positioned the longest legs to form the gorge.

The shear geometrical uniformity of Mahan's forms made them difficult,

if not specifically impossible, to apply in practice and even Mahan warned

that these forms were not to be restricted to the limits imposed by his

description of them.

even better protection for the salient angles than Mahan's

arrangements since the entire length of each redan's face crossed its column

of fire in front of collateral redans' salient angles. As with Mahan's

forms this type of tenaille line had a geometric beauty and orderliness that

was almost impossible to translate into concrete structural form on uneven

ground.

even better protection for the salient angles than Mahan's

arrangements since the entire length of each redan's face crossed its column

of fire in front of collateral redans' salient angles. As with Mahan's

forms this type of tenaille line had a geometric beauty and orderliness that

was almost impossible to translate into concrete structural form on uneven

ground.

required more linear yards of parapet and ditch to fortify

a given position than any other type of line. This also meant that tenaille

lines required more troops to man the parapet than other forms. The large

redans of Mahan's first arrangement, for example, required 320 yards of parapet

to fortify a position that was only 160 yards wide. Given the idea that a

good defense required at least one man per yard of parapet, 320 men would

have been required to defend each redan. By comparison a standard cremaillere

line on a front 160 yards wide required about 190 linear yards of parapet

and the same number of men to adequately defend it. Assuming that an army

taking up a position behind a continuous line did so in an attempt to match

its opponent's numerical superiority with field fortifications, the

fewer men necessary to defend a given section of front, the better chance

its would have been to counterbalance the enemy's advantage. The extra 130

men necessary for each redan in a tenaille line would have been better used

to create a strong reserve. Tenaille lines required too many men and too

much labor compared to other types of lines to have any practical use in

the field.

required more linear yards of parapet and ditch to fortify

a given position than any other type of line. This also meant that tenaille

lines required more troops to man the parapet than other forms. The large

redans of Mahan's first arrangement, for example, required 320 yards of parapet

to fortify a position that was only 160 yards wide. Given the idea that a

good defense required at least one man per yard of parapet, 320 men would

have been required to defend each redan. By comparison a standard cremaillere

line on a front 160 yards wide required about 190 linear yards of parapet

and the same number of men to adequately defend it. Assuming that an army

taking up a position behind a continuous line did so in an attempt to match

its opponent's numerical superiority with field fortifications, the

fewer men necessary to defend a given section of front, the better chance

its would have been to counterbalance the enemy's advantage. The extra 130

men necessary for each redan in a tenaille line would have been better used

to create a strong reserve. Tenaille lines required too many men and too

much labor compared to other types of lines to have any practical use in

the field.

the Civil War.

At Fort Henry on the Tennessee River the Confederates constructed a line

of "rifle pits" (which actually had the profile of breastworks) that employed

a series of repeating redans joined at the flanks as outworks to cover the

north and northeast land approaches to the main fort on the river bank. The

general form given the line resembled the third equal sized redan arrangement,

but in this case the redans' salients were mashed in and given very obtuse

angles and the faces did not join to form 90 degree re-entering angles. Though

the faces crossed their columns of fire at a distance, the angles used did

not allow reciprocal defense for collateral redans which negated the one

important advantage that the tenaille form had over other types of lines.

The repeating angular form given the line at Fort Henry seems to have been

intended solely as a means of breaking the continuity of the parapet and

preventing the entire length of the line from being enfiladed by distant

artillery fire.

the Civil War.

At Fort Henry on the Tennessee River the Confederates constructed a line

of "rifle pits" (which actually had the profile of breastworks) that employed

a series of repeating redans joined at the flanks as outworks to cover the

north and northeast land approaches to the main fort on the river bank. The

general form given the line resembled the third equal sized redan arrangement,

but in this case the redans' salients were mashed in and given very obtuse

angles and the faces did not join to form 90 degree re-entering angles. Though

the faces crossed their columns of fire at a distance, the angles used did

not allow reciprocal defense for collateral redans which negated the one

important advantage that the tenaille form had over other types of lines.

The repeating angular form given the line at Fort Henry seems to have been

intended solely as a means of breaking the continuity of the parapet and

preventing the entire length of the line from being enfiladed by distant

artillery fire.