|

|

|

And then there was Leningrad - the great city of Peter and Lenin, city of the revolution that shook the world, city of beautiful architectural ensembles, palaces, and museums. But it couldn't be recognized now. It was a different Leningrad, cold, harsh, frontline city, gloomy, darkened, covered with frost and filled with snow. We unloaded at a freight station. Guns, caissons, carts, wagons, and anything pulled by horses was sent through the city under its own steam. Trams with frost covered windows arrived for the unmounted personnel and carried us through the dark frozen streets to the northern end of the city. We passed through the city and got off in a suburban village, where we billeted in the peasant houses in terrible overcrowding. But we were glad for any shelter during those strong frosts. The officers were called for instructions. We were ordered to march the next day, cross the Finnish border, and enter the battle zone. To be prepared for any vicissitudes of war. Already in the night, exhausted, I returned to the house where my platoon was camped. I opened the door but couldn't go further than the threshold. Worn out soldiers laid side by side on the benches, on the floor, packed close to one another. I sat down on the threshold, then laid down in the same spot and fell asleep.

The 306th Rifle Regiment participated in the Finnish Campaign as a part of the 62nd Rifle Division. This division was formed in Belaya Tserkov' and Fastov in the Kiev Military District. It was put into the 13th Army on the Karelian Isthmus by the 18.01.1940 order. It received an order to concentrate around the village of Lipola (right on the border) on 30.01.1940. The division arrived to the front on 03.02.1940 and on 17.02.1940 was transferred to the 23rd Rifle Corps from the 13th Army reserve. Relocated from Lipola to Kangaspelto on 17-20.02.1940. Participated in the offensive on Volossula on 19.02.1940, Kelya 20.02.1940, was located in the area of Mutaranta for the period of 21-23.02.1940. Entrained on 21.03.1940 and moved to the Kiev MD from Leningrad. The information is taken from the first volume of "Greet Us, Beautiful Suomi", Volume 1, St.Petersburg 1999, ISBN 5-8172-0022-8, editor - Yevgeniy Balashov, published by OOO Galea Print. Bair Irincheev

Excerpt from a stenography of the April 14-17, 1940 conference of senior army officers at the Central Committee of the Communist Party. Contained a speech of colonel V.V. Kryukov commander of 306 rifle regiment.

We formed a marching column in the morning and approached the Finnish border, which, as it turned out, closely adjoined Leningrad's suburbs. We were struck. A huge city, one of the most important centers of our country, was next to the border with a hostile state. Border posts and "no man's land". From our side of the border, in open spots not protected woods, wire nets with fir and pine branches entwined were set. As it turned out, that was our border guards' camouflage against bandit shots from the Finnish side. And so, after the Polish one, we crossed our second border. Because it was necessary.

The Finnish land. Houses burned during retreat, bridges blown up, black craters from shell and mine explosions. Signs were placed in some spots, saying that all movement should only be conducted on the road, since mines camouflaged with snow had been placed on the sides. Field phone wires, abandoned by Finns, were very noticeable in the snow, thin, light, in colored plastic insulation. Our communication wires were heavy, steel ones, in thick black insulation. Metal reels of such wire were heavy, and couldn't be easily rolled and unrolled.

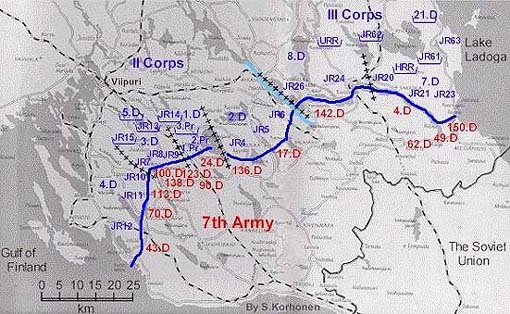

The front line in the Karelian Isthmus February 1st

1940. |

The frost was horrible. Riding was impossible. We walked, leading the horses. Horses' fur was covered with frost. Combat engineers built fires along the roads over which our troops were moving. You could warm yourself a little, even if suffocating in the smoke. Toward the end of this first day we stopped for the night in the quarters of a combat engineer unit, which looked after roads and fixed bridges. It was located in warm sheds and barns of some estate, whose main buildings and houses had been burned by Finns during their retreat. These sheds and barns seemed almost like palaces to us. The combat engineers' hospitality, something that occurred rarely, was very touching.

The next day we started approaching the front itself. First thing that struck us were the frozen corpses of our soldiers and officers lying there, already powdered with snow. They lied here death found them, in various positions. We were used to treat our dead with respect. A coffin, funeral service, the celebration of farewell, everyone around whispering, covering mirrors, stopping their watches. But here, it was as if contempt toward death was underscored. As if they were saying to us, those going forward, that death was an ordinary occurrence in his place. They were killed, so let them lie, nothing extraordinary had happened. There was war her, and everything was different from the way it was in civilian life. You had to get used to it.

Soon we approached the frontline, which had the latest line of Finnish fortifications before it. Units of our forces to the left and right gladly made room for us, giving our division a separate sector. I heard later how infantry officers said with malice that the "neighbors" had opened up the hottest spot for us, withdrawing to quieter sectors.

Yes, we came to the "Mannerheim Line". Lines of concrete pillboxes, bristling with muzzles of artillery pieces and machine guns, stood on sandy wood covered hills. Unfreezing "windows" were cut in the ice of lowland swamps between the pillboxes, in a checkered pattern, filled with oil and powdered by snow on top. Falling into such "window" meant certain death. Besides, the area between the pillboxes was exposed to cross fire from the pillboxes.

We stopped. Our 306th Regiment was put in front, the other two regiments of our division deployed behind us, in reserve. As always, we were the "lucky" ones. Started digging to construct shelters. The soil was frozen, we had to blow it up with TNT. We cut down pines for the roofs seeing that wood was in excess in these parts.

For some reason I needed to see the politruk, so I started looking for him. They said he went to get vodka for the battery. I couldn't believe my ears. A teetotaler who ruined our New Year celebration out of fear that we'd drink a glass of light wine, and this man went to get vodka. But it was so. They started giving us 100 grams of vodka a day. It warmed and cheered us during frosts, and it made us not care in combat. In about two days, after we had reached the frontline, the regiment's chief or artillery called all officers of the battery. Announcement was made that the assault of enemy positions was to be the next day. And today, some senior officer from the division's HQ would take a group of officers to reconnoiter. I returned to the battery to tell my deputy platoon commander to take over during my absence. Two of my signaler soldiers started asking me to take them with me "to look at the Finns". I agreed reluctantly.

And so, a group of infantry and artillery officers, 12-15 men, set out of the camp and went northward into the forest. We walked single file over a narrow trail made between deep snow drifts. The senior officer was in the lead, we followed. My curious signalers were bringing up the rear. There was a chain of hills to the right of us, and a hollow sloping downward to the left. The morning was beautiful: frost, blue sky, sunshine, and silence. The only sound was snow squeaking under our feet. We went deeper and deeper into the forest. I looked and couldn't understand, where were our positions, where was the infantry, where were our forward detachments? There was nothing like that, although we had walked pretty far from our camp. There were only pines, snow drifts, and deceptive silence. A feeling of danger and alarm was growing. My signalers, who were walking behind us, started falling farther behind. Apparently, they understood that we were being led straight to Finns for a visit. Suddenly, the forest ended in a perpendicular ravine, and we exited to a clearing. A small frozen river was running on the bottom of the ravine. A bridge was constructed over it, blocked by a barricade of huge rocks. On the other side of the ravine, right in front of us, in no more than 100 meters, the bulk of a concrete pillbox towered, looking at us with cannon and machine gun muzzles through its embrasures. Some people could be seen behind the pillbox, digging communication trenches in the snow. I couldn't believe my eyes. We had been taken into open ground right under the guns of the Finnish pillbox. All our group could be cut down by one machine gun burst. Some sled stood next to us, with a bright blue enamel pot, which sharply contrasted with the white snow. Apparently, that was the point to aim at.

Meanwhile, the senior officer lectured, waving his arms: "The guns should be put here to fire over open sights, the infantry will advance along the bottom of the hollow," - and other things along those lines. My thought worked feverishly: "Why don't the Finns shoot? If they can see us very well?" Two of our group, heartened by the pillbox's silence, descended and started throwing the rocks off the bridge. The senior officer went droning on with his instructions, but the pillbox remained silent, why?

And then, suddenly breaking the silence, shots rang behind us. I looked back. My signalers, who stood on the trail far from us, were shooting their rifles to the left, into the hollow. There, between the trees, figures of skiers in white coveralls appeared, they were getting into our rear, aiming to cut our line of retreat. "Finns!" - I yelled, and the entire group ran back in panic, getting tangled in deep snow. Now it became clear why we hadn't been shot at from the pillbox. They wanted to take us alive by barring our way back. What could we have done with our handguns, sinking in the deep snow, when a detachment of Finns with SMGs surrounded us? Half of us would've been killed, the other half taken prisoner. The enemy needed information about the attacking forces, and they would've tortured it out of those that remained alive. What luck, that the Finnish skiers ran into my signalers, and they started shooting at them. The Finns, of course, couldn't even surmise that only two soldiers turned out to be behind our group (even that by accident), and not a guard platoon. That's why they didn't dare to complete the encirclement.

Our group walked back quickly. Some openly cursed, others were gloomy and silent, understanding how this escapade might have ended. One of us laughed nervously at what happened, trying to cover the scare he received with laughter. The senior officer tried to start talking about something again, but no one was listening to him anymore, everybody tried to get out of this dangerous forest as soon as possible. We were returning to our camp. But the first thing we saw was not our forward detachments, and not the line of infantry, but a field kitchen and a cook, stuffing snow into his pot. Someone from our group told the cook that it had been a bad idea to come so far out, that the Finns were close. "What Finns? I'll get them with my scoop!" Such attitude was characteristic for the majority, until we were soundly bathed in our own blood. Of course, no one thanked me for taking the soldiers that saved our lives with us. The real operations and danger were still ahead.

The day was spent in preparation for tomorrow's battle: I was checking radio and telephone equipment. We were again called for commanders' briefing in the evening. When I returned to our dug-out at night, raised the cloak at the entrance and lit the inside with my flashlight, I was horrified. The soldiers were almost stacked, sand was falling from above - the dug-out was small. I went to spend the night to our politruk. He had a small round tent of his own, with a stove. The politruk was "preparing" for tomorrow's battle by sawing a white collar to his uniform. I went to bed at his place, without undressing, right on the floor, which was made of snow covered with pine branches.

The morning of the first battle. I, together with my signalers, was ordered to follow the fire platoons with a cart loaded with radio and telephone equipment, and be prepared to establish communications on demand. We entered the forest after infantry. The first killed soldier of our regiment was lying in the clearing. That meant that Finns had advanced to the clearing at night to meet our attacking units. A helmet punctured by a bullet and a gas mask, whose ribbed tube was covered with blood, were lying next to the dead soldier. The first corpse, it had started.

We were moving along the forest road toward yesterday's pillbox. Yells of "Hurrah!" already sounded there, explosions and machine guns could be heard. The first wounded appeared, with fresh bandages, moaning. According to the field manual, the evacuation of the wounded must have been conducted along a road different from that taken by the approaching fresh reinforcements, so as not to wear down their fighting spirit. But who thinks of such things during combat? Mortar shells were flying toward us here and there, and their explosions raised fountains of earth and snow. I was walking to the left of the cart, sinking in the snow. Suddenly, something made me cross to the right side, although the road was worse there. I barely made several steps when a squealing mortar shell hit the spot to the left of the cart, where I had just been walking. It buried itself deep in the snow but didn't explode. Had I not crossed to the other side of the cart, I would've been killed. But even the other side would not have saved me had the shell exploded. Luckily, not all Finnish shells exploded, which was fortunate. Later, I found out that some shells had been given to the Finns by the western allies from their old stockpiles: "God, accept what doesn't suit us."

What made me leave the spot where the shell hit a minute later? Apparently, it was instinct, the one that makes an animal leave places where a hunter's bullet might find it. Let's think of it that way.

The infantry was assaulting the pillbox from the front, taking huge casualties. But it could've been bypassed and taken from the rear, where it didn't have any embrasures with artillery and machine guns. But you couldn't criticize the superiors. They were infallible like Caesar's wife. In the end, we managed to capture the pillbox. A flame-thrower tank arrived and directed its fountains of fire into the embrasures (Most probably it was flamethrowing T-26 - Valera Potapov). The Finns ran away. Their retreat was covered by a small machine gunner, who pulled his machine gun to the top of the pillbox, and perished heroically while returning fire. When our infantry moved on in pursuit of the enemy, I ran to look at the captured pillbox. And almost paid for my curiosity. When the pillbox fell, the neighboring pillboxes, still in Finnish hands, opened artillery fire on it. Several shells exploded, which fortunately did not cause any harm. Thick walls of reinforced concrete were covered by armor plates with powerful shock absorbing springs. That's why armor piercing shells were not penetrating the walls, but were deflected from them. Corpses of our soldiers were lying in front of the pillbox, some of whom were burned by the fire of the tank's flame-thrower and squashed by its tracks. Because the flame-thrower tank arrived later (And why couldn't it have come earlier?) and ran over the corpses. A hard and horrible sight.

The corpse of the small Finnish machine gunner was lying in front of the entrance to the pillbox, and our soldiers entering the pillbox were kicking it with hatred. The machine gun was also lying there. It was an old Maxim model. I looked at its plate: "Imperial Tula Factory. 1915." Such are the twists of fate. Russian arms against Russians.

|

Flamethrowing T-26 in action. |

Some of the internal furnishings of the pillbox had been burned by the flame-thrower. I saw a large copper coin on the table, probably a good luck charm of one of the pillbox's defenders. I grabbed it greedily. It was an old Swedish coin with three crowns. After leaving the pillbox, I ran into our battery commander: "Look," - I practically yelled, - "what a find! This is an old Swedish coin, probably XVII century, possibly King Vaaza's." The battery commander took the coin from me, looked at it, and suddenly swung his arm and threw it far into a snow drift. "You are not allowed to have foreign currency," - he lectured and walked on pompously. I was outraged. More than forty years have passed since then, many events happened, but I'm still mad at the moron battery commander, and I'm endlessly sorry for this coin, which could've made a valuable addition to my numismatic collection and would've been such a memorable souvenir.

During that first day, besides the infantry assaulting the pillbox, many other people who ran forward to "look at Finns" suffered. Our battery's artillery technician, who had absolutely no business in front, perished in this way. When they were carrying him, heavily wounded, past us, he screamed to the battery commander that he was freezing. Indeed, the frost was such that not the wound itself was terrible, but that you would be undressed to bandage the wound out in the cold. The artillery technician died in the medical battalion the next day. Several men of our battery were also hit when they were trying to roll the gun forward to fire over open sights.

They said that before the first battle some commissar talked to the soldiers who were supposed to assault the pillbox and called them to feats of heroism. When the time to advance came, the commissar started saying good-bye, but the soldiers said: "Let's go with us, comrade commissar." I saw the corpse of this commissar. He laid face down together with the soldiers' corpses and differed from them only by the gold buttons on his greatcoat's half-belt.

That day, after the battle, only the infantry advanced after the retreating Finns, but our battery remained there for the moment. For the first time we had to spend the night under open sky in the frost, sitting near fires because our dug-outs were filled with wounded. That meant that the medical battalion was also full. It's bad to sleep while sitting in the frost by a fire. You get burned on the front, but the back freezes. When dozing off you lean forward and your clothes catch fire. Damn war.

We began advancing with combat. When retreating, Finns painfully snapped at us, burned all buildings, set mines everywhere. During a hasty retreat they even burned down barns with cattle inside. They killed dogs that didn't want to leave their burning houses. They set mines to the side of trails they used to retreat. But when the trails turned into roads for trucks and tanks, explosions began. Light ski detachments with mortars, which they transported in small sledges, were opposing us. They also used these sledges to carry away their killed and wounded. They used forest obstructions, any natural obstacles like granite protrusions, which were plentiful there. They opened automatic fire from cover and inflicted heavy casualties on our forward detachments. But when we brought up artillery and fired over open sights, they changed their position, appeared on our flanks, and everything began anew. Then they suddenly disappeared to meet us on the same road at the next obstacle.

The enemy retreated, leaving not only mines, but also colored leaflets for us, which sharply contrasted with snow. They were very naive, intended for morons. Some threatened that the world powers would soon move against us, others persuaded to abandon arms and return home to families, which were missing us very much, etc. Apparently, those were composed by the White emigrants who believed that our soldiers had remained on the level of the pre-revolutionary village.

Combat was conducted primarily during the day. Everything grew still toward the night, and signalers' work began. Under the cover of darkness, we had to roll up old wires, provide communications to the new artillery positions by connecting them to observation posts, connect to the regiment HQ and the artillery chief. Everything had to be ready by morning. The night was sleepless during such work, and combat began in the morning, so how could you sleep when the communications got interrupted here and there? Of course, there happened such nights when you could sleep, sitting by a fire or (really nice) in the ashes of a burned house. There, the earth heated by the fire would keep warmth for about two days, but not longer.

We mainly used telephone communications. Radio was unreliable. Our radio sets (6PK) were cumbersome, with little power, transmitting to short distances, often jammed by various interference. Additionally, all transmissions had to be encrypted, which hindered flexibility of their usage.

Another problem awaited us. Our telephone wire started to wear out quickly, break, and get damaged. Less and less of it remained. The regiment's communications chief needed wire himself and couldn't help us. There was so little wire left, that in some sectors guns, due to its lack, had to be rolled out of cover to fire over open sights, under the fire of Finnish soldiers with SMGs, and our men were getting killed to no purpose. We had to mostly lay one line: battery commander's command post to the firing position. There became less work for signalers. But the battery commander quickly found something to keep me busy. The battery took heavy casualties by that time. Both fire platoons had to be merged into one because only two out of four guns remained operational. The others were mangled. Our strength was also halved. The merged fire platoon was commanded by Lieutenant Kapshuk, a young Ukrainian and a regular officer. One night I was woken up by the duty telephone operator: the battery commander was calling me. I picked up the phone. "Do you know that Kapshuk's been killed?" "Not yet." "Take command of the fire platoons, they're to be ready for combat by morning. Your deputy platoon commander can manage with the communications." In the morning of the next day I was already in the artillery position commanding the fire. The battery commander was correcting the fire from his observation post by phone. While commanding, I stood behind the guns, in the spot where Kapshuk had stood several hours ago and had been killed. And the poor Kapshuk, yesterday still ruddy and merry, laid nearby, wrapped in blood covered ground sheet, and waited to be put into a sled and driven to the medical battalion, where they blew up the frozen Finnish soil with TNT and buried corpses in those holes. Everything was simple to the extreme, and unavoidable like fate...

The 76.2 mm Regimental Cannon Model

1927 in action.

|

Soldiers of the fire platoons were gloomy, mechanically obeyed my orders, and tried not to look in the direction where the corpse of their late commander laid. Getting ahead of myself, it must be mentioned that my "promotion" did not end there. We took such casualties among soldiers and officers, that toward the end of the battles I was appointed deputy battery commander, in case of the commander was incapacitated. Fortunately, that did not happen. It was hard to knock out our oaklike battery commander.

During the war I got a letter from mother at home. She wrote that a summons for me from the military commissariat had been received with an order to come "with personal belongings." Mother went to the commissariat with the summons and explained that her son had been mobilized half a year ago. They took the summons and said that it had been a mistake. But in several days they came at night to search our apartment, and having dragged my old mother from her bed, started asking where her son was. At the same time others were unceremoniously looking under the bed, into the closet, the bathroom. Mother became indignant: "It is I who should ask you where my son is! You mobilized him this autumn. He honestly fights at the front and doesn't walk around at night to look under beds." The visitors saw my photograph in military uniform and letters with postmarks of the acting army field post office on the cupboard. The night guests retreated abashedly and, of course, forgot to apologize. Such was the state of affairs in our Bauman Military Commissariat of the City of Moscow.

One morning I left the battery and went to the forward positions, where the battery commander's observation post was located. The road went through forest and was deserted at that hour. I met some soldier. I didn't know who he was, since we had been ordered to take off our insignia. When closed on each other, I asked him familiarly: "So, how are things there, quiet?" He made a scornful face and asked: "What are you, afraid?" I blew up and also replied with a question: "I don't know who's more afraid: someone who walks to the frontline, or someone who rushes to get away from there." I heard obscene cursing in reply. The stranger introduced himself.

I also had conflicts with our battery commander. Once, when I was at the battery which had been deployed in the woods, he called me on the phone and told be to come to a clearing. Ahead of us, in a clear spot, there was a hill which our infantry was assaulting. "Lay wire to that hill," - the battery commander said. - "Go there yourself and command the firing from there." "But the Finns are still there," - I replied, looking through the field glass. - "When we capture that hill, I'll go there with a telephone operator and lay the wire." "Go now", - the battery commander said harshly, and his hand suddenly fell to the unbuttoned holster of his handgun. This made me indignant. He threatened me when the forest around us was already filled with singing of bullets and the squeal of mortar shells. "Comrade senior lieutenant," - I said - "I repeat that I'll obey your order as soon as the infantry takes that hill. As to you handgun, I have exactly the same one. If you can't wait," - I continued - "let's go there together. Our handguns will come in handy there." Somehow, the battery commander didn't like my proposal, and he fell silent. "Allow me to first tell the battery to advance to this clearing, otherwise we will not be able to secure an arc of fire." "Do it," - the battery commander said, apparently, having cooled off and realized that he had gone too far, and walked away pompously.

The enemy had almost no air force, or it wasn't active in our sector of the front. Only once have I seen how our positions were attacked by several Finnish aircraft like our U-2, which dropped bundles of some grenades. They had black crosses on blue background painted on their wings. But somehow we didn't see our air force either.

"Cuckoos" - snipers in the trees - were bothering us a lot. During retreats, the Finns would put them in the trees with a submachine gun and a large quantity of ammo. Some of them shot and then ran away on skis, which they had left under the tree. Others shot until the end, until they were themselves knocked from the tree, and finished on the ground with hatred. Sometimes four "cuckoos" would deploy as if at the vertices of a forest square, and then anyone who entered that square was unavoidably killed. It was hard to knock them off, since they concentrated the fire of four submachine guns on one target in case of such attempts. They changed their position during the night, moving on to the next "square". Finns took the boots away from some snipers before putting them in the trees, so they wouldn't run away, and replaced their boots with a blanket. There was a case in our regiment when soldiers, having seen a "cuckoo" sitting in a tree, fired at her. She immediately threw down the gun and the blanket off her feet. The "cuckoo" turned out to be a young red-haired girl, white as death. They pitied her, and when they gave her some burned valenki, and she realized that she wouldn't be killed, she wept. Hearts melted and she was sent, untouched, to the rear under guard.

The mention of female cuckoos and a pillbox with armored plates installed on springs so that shells would bounce off it is very interesting. This shows that even educated people in those times believed and continue to believe in those myths. As to the pillbox in the area where this officer fought - there wasn't a single million pillbox there, all pillboxes had 1-2 machine guns, were built in 1930s, and were of high quality. The mention of flame-thrower tanks is indicative because flame-thrower tanks were used intensively during the assault on those two strongpoints - Salmenkaita and Muolaa. There is a pillbox among the fortifications of Muolaa, which I visited, whose entire garrison was completely burned by the flame-thrower tanks. Bair Irincheev

Generally, they fed us well during combat. Field kitchens with soup, kasha arrived to the frontline, and filled anyone who approached. The cooks hastened to give out the food and leave the way they came from under mortar fire. They were not allowed back with any food remaining. They said that one cook had been shot on the spot because he emptied the tank of his kitchen into the snow in order to get away from the front line as soon as possible. Of course, there were days when we melted tasteless snow for tea, warmed the frozen ice-covered bread in the smoke of a fire, and boiled wheat concentrate in mess tins.

Our regiment drove a deep narrow wedge into enemy positions. Uncaptured pillboxes remained to the right and left of us, and we often got into cross fire. Our flanks were weakly guarded, we only had medium machine guns deployed in some places. One night, when I was sleeping with my soldiers on straw placed over snow, a machine gun started firing nearby. I jumped up and ran to the machine gunner. It was dark. I asked why he was shooting. The soldier was silent at first, then he muttered: "If you don't shoot, they'll come here as well."

During a severe frost, we officers were given sheepskin jackets. But soon they had to be taken off. Finnish snipers started to knock off officers. Not only snipers, but Finnish skiers as well, having dressed themselves into Soviet uniform, went into our positions, stabbed our officers, and got away. That's why we were ordered to take off not only the sheepskin jackets, but also the insignia from our tabs, the red "angles" from the sleeves, and wear the belts under the greatcoat.Once I was ordered to take a telephone operator and, having laid a wire to the command post of an infantry element, be there myself, calling the battery's fire as necessary. The command post was located in a low dug-out whose floor was covered with straw. Everyone sat right on the floor. Soon, the battery commander called me on the infantry phone. Although I was dressed as a simple soldier, the infantry telephone operator turned to me: "Comrade lieutenant, it's for you." "Why do you think I'm a lieutenant?" -- "I see that you're a lieutenant, you talk differently." It turned out according to the proverb "You can see a priest even in rags."

There was a case in a neighboring unit when a Finn, dressed in Soviet uniform, came on skis to a field kitchen. Cook said that he didn't know him and could only feed him if the commissar allowed it. "And where's commissar?" - asked the Finn. The cook pointed out the commissar, who was wearing a soldier's greatcoat. The Finn approached the commissar, stabbed him, and ran away.

There were many cases of atrocities, when Finns used knives to kill our wounded, who hadn't been removed from the field yet. I saw myself how several bodies of our soldiers lied in a clearing that couldn't be approached because of shooting "cuckoos". And when one of them made an attempt to get up, shots were fired at him from the trees in the forest. One wounded soldier told of how when he was lying wounded in the snow after a battle, a Finn skied over to him and said in Russian: "Lying there, Ivan? Well, go ahead." It's good that he didn't finish him off, because there were many such cases.

The casualties in our battery were significant. I remember one of my signalers, a young lad, who had just graduated from school. He drew well, was undoubtedly talented, and dreamed of going to the Arts Academy. I often talked to him, looked at his drawings, helped him with advice. I was endlessly sorry when he died in the medical battalion after being wounded. The infantry losses were more significant. There were many tragedies. They told of one young lieutenant who had been wounded in the face, losing both eyes. They didn't have time to take his gun away, and he shot himself right there in the trench, as soon as he realized that he had been made blind.

One night I walked through the forest checking the phone wire laid previously. I crossed a small clearing to enter the forest again. The forward positions were somewhere nearby. The moon shone brightly in my face, blinding my eyes, snow sparkled. Having entered the forest again, I immediately ran into a man in a white coverall, so unexpectedly and close that I threw my arm forward and pushed this man in the chest with my hand. I felt how my heart stopped from fright. The sudden obscene cursing that cut into my ears sounded like divine music: "Ours, Russian." It was our scout, who, seeing me crossing the clearing, decided to wait in the frost. The enemy wouldn't fire mortars at one person, but they could do so at two.

There was another case. After occupying a new command post, the battery commander called me on the phone and told me leave the battery and come to him. He went there during the night, behind the infantry. But during the day the situation had changed. The road was crossed by a frozen river in one place, and that crossing was being shot at by a Finnish sniper. He set himself up on a rocky islet in the middle of the river and fired his submachine gun at anyone who tried to cross on the ice. There was no possibility of covertly sneaking up on the sniper, he had an almost all-round field of fire. Huge boulders protected him from bullets. Many soldiers and officers who needed to cross the river assembled in the forest on both sides. From time to time someone would decide to run to the other side under the hail of bullets, and it worked. But there were cases when the wounded fell on ice. They would crawl to the opposite bank. The only protection for the runners was provided by a burned out Soviet tank in the middle of the river. Of course, if there was a mortar available, we could've quickly shut up that rogue. But there was no mortar, and no one cared about that.

I also had to cross. The sniper fired double shots with pauses. I got behind a tree next to the river and waited. After the shots had been fired, I ran to the tank. As soon as I reached it, bullets started knocking on its armor. Having caught my breath, I started waiting for the next burst, and when it ended, ran further. This part of the way was longer, and I barely managed to hide behind the trunk of the first tree of the opposite side. Whew... Several days later, after the Finns had been pushed out, and we were dragging our guns through that cursed place, I went to take a look at the islet. There was a hole dug between and under the huge boulders, covered with pine branches, with an embrasure in the direction of the road. Empty cigarette packs saying "Sport" on them were lying around, and plenty of spent copper cartridges. The cartridges of the bullets the sniper had shot at me were among them. That's the kind of "sport" it was.

Before the start of fighting they announced to us, officers, that out of three rifle regiments of the division each will fight ten days, taking turns. How we waited for the end of these first ten days. We waited, drowning in our blood, sending our comrades to either the medical battalion or a grave. But, alas, we were not replaced even after ten days. When the division commander found out about large losses in the 306th Regiment, he decided that it wouldn't do to destroy the other two regiments in the same way. After changing his original decision he uttered: "When I wear the 306th out to the end, then we'll think about replacement." Indeed, we were not replaced until the end of the war, and got so worn out that only "hoofs and horns" were left.

This horror, these endless battles, went on for 22 days. We turned into some half-beasts: frostbitten, dirty, lice infested, unshaven, in clothes burned from the fires, unable to say a single phrase without obscene cursing. And constantly in danger of being wounded or killed at that.

And suddenly, if I'm not mistaken, March 11th, in the evening, one of my radio operators ran to me with striking news. He accidentally received a transmission: an armistice had been signed. I ran to our politruk, but he yelled at me, that I believe all kinds of rumors and spread them at that. But such news could not be held secret for long. By the expression on soldiers' faces I understood that it had spread quickly. Some asked me for confirmation, but I replied that I didn't have any official information. The morning of the next day came. It was March 12, 1940. Everyone waited for something. But then the battery commander called from the forward observation post: "Battery, prepare to fire!" I gave the order: "Crews, to your guns, prepare to fire, bring up and wipe the shells!" Soldiers moved reluctantly. Some grumbled: "Here's peace for you." The battery commander gave the target's coordinates, I aimed the guns and: "Fire!", and again "Fire!". Finns started replying with heavy mortars. Shells fell to the left, in front of us, at the crossroads. Some horse cart was hit there, and the poor horse with its belly ripped was getting entangled in its own guts. It was a horrible sight. But the battery commander at his observation post kept demanding: "Fire!" and "Fire!"

|

It was around 10 in the morning when a galloping horseman appeared on the road leading from the rear, he was yelling something and waving an envelope. Closer, closer. We recognized a runner from the regimental HQ, a short merry soldier, who'd been in our battery many times. He was yelling: "Stop the fire!" What happened then! Some yelled "Hurrah!", some kissed each other, someone cried, and some simply fell to the snow. I took the envelope with shaking hands. It wasn't sealed. It was an order to the battery commander to stop the fire. The telephone operator called me to the phone. The battery commander was yelling at me: "Why did you stop the fire?" I also yelled that such was the order from the headquarters, they said it was peace. "What peace? You lost your mind there!" But the artillery fire was falling silent along the entire front. And if some late shot was fired, soldiers grew indignant: "What's wrong with them, don't they know?!" After the initial burst of happiness, some sort of a reaction set in. Strength left, everyone fell silent and froze, not knowing what to do next. Witnesses later told of how the news was greeted in the forward positions of the infantry line. Cold, tired soldiers, both Finns and ours, crawled out of their holes on both sides of the "no man's land", looking with suspicion and surprise at their recent enemies. And they couldn't understand. What happened? They were silent, making fires to warm themselves. Some Finn got on top of a huge boulder and yelled to our soldiers: "Russian, Russian, you were shooting at me, I was sitting here under this rock!" Another Finn yelled through the "no man's land": "Don't go right, we set mines there."

And so, peace. We were pulled back a little and ordered to build dug-outs. We started putting ourselves in order. They brought in a field bathhouse with a delousing chamber. It was needed. Nothing to hide here, lice were devouring us. We washed in three consecutively set up tents. We took off our uniforms and gave them to be roasted before entering the first tent. The snow floor in the tents was covered with evergreen branches. We took off our dirty underwear in the first tent, in the second, a network of pipes poured hot, almost boiling, water on us, then we ran to the third tent where we received clean underwear, which we put on our wet bodies because there was nothing to dry ourselves with. And then we waited, well stewed, in just our underwear, until our uniforms were finished being roasted. And all that in the cold, since it was almost as cold inside the tents as outside. I still don't understand how we managed not to get a cold or pneumonia. But we were happy to have even such a bath.

About two weeks after the end of the fighting, after we had rested a little, got ourselves and our weapons in order, we were ordered to march back. The regiment formed a marching column. And only then we could see for ourselves the casualties that the regiment had suffered. The regiment came here at full wartime strength. Infantry consisted of three battalions of 700 bayonets each. Now, there wasn't enough infantry to form a single battalion. Companies were commanded by sergeants. We, battery men, also took heavy casualties. Out of nine officers of our battery only four remained. Two were killed and three wounded. Even I, a reservist, had to be appointed deputy battery commander in case he was incapacitated. I don't remember any more how many privates and NCOs the battery lost. We marched here in several columns, so huge was the regiment. Now the entire regiment formed a single column, and we artillery men, walking in the end of the column, could see and hear the band playing marching tunes in the lead of the column. We marched past the place where the medical battalion had been deployed and the cemetery was located. The medical battalion had already packed up and left, but the cemetery remained.

If we didn't see corpses, these horrible frozen wax mannequins, then death would not have been so terrible. In civilian life, death of a sick person does not come as a surprise. But it was absurd to see the arrival of death to a young healthy man, who suddenly drooped in your arms like a sack, his face became yellow, corners of his mouth and eyelids fell. And you could see the entire horrible evolution, the ease of transition from one state to the other, to a sad hillock made of frozen lumps of the cursed Finnish soil.

It's hard to express in words what we felt while walking past this cemetery. Not too long ago these men, our comrades, young and healthy, were among us and were the same as us. Even when they were put here, and any one of us could be put next to them any minute, we didn't feel alienated from them. And now we were leaving them forever, and they forever remained to lie here. And an abyss formed between us and them, and we couldn't understand with our minds how and why it all happened.

Of course, we realized that this war was necessary. We had to make Leningrad safe, separate it from the dangerous border by a zone of Soviet land. We also knew that Finns refused the offer of the Soviet government to exchange this territory for any other along the border. We couldn't understand a different thing - the method in which the war was conducted. Couldn't we just bomb the Finnish pillboxes from the air, block them, bypass, and leave them in the rear?! Like the Germans did with the Maginot Line? Couldn't we drop airborne troops into the Finnish rear, use tanks more widely? We saw a lot of this equipment sitting in sidings at Bologoye. No, they chose to throw people chest first into machine gun and artillery fire of pillboxes, in bright sunny days with clear view. And put thousands of young men into graves. Why? Or maybe they thought the same way as that "strategist" who led us to a Finnish pillbox before battle, thinking that it was a training box of sand with tin soldiers before him, and started explaining how to fight. All that was incomprehensible and vexing.

After the peace treaty had been signed, newspapers reported that our losses in killed and wounded were somewhere around fifty thousand. How many tragedies hid behind these numbers! These losses could've been significantly smaller!

The regiments of our division that had been deployed behind us in reserve during battles, were turned back first and were first to parade through Leningrad like heroes. They got the celebratory reception, greetings, and gifts collected by Leningradians. And when our 306th regiment, or, rather, its remains, entered the city, a real fighting unit which bore all the hardships of war on its shoulders, the celebration was already over, and we didn't receive any gifts. That's how it happens in life.

Later we found out that our regiment was awarded the Order of the Red Banner for the breakthrough of the Mannerheim Line. Several officers of our regiment's rifle units also received orders. Awards were scarce in those days. Our artillery and mortar men didn't receive anything, although the award lists for us were supposedly put together. But to have survived with your head intact was also not a small award.

When we were leaving Leningrad and were loading at a train station, we saw another sad picture. Several freight cars, whose windows had been barred with barbed wire, stood separately on a different track. Guards with bayonets attached to their rifles did not let anyone approach those cars. A railroad worker whispered to me that those were from Finland, our servicemen who had been taken prisoner. Until that time we thought that those who went through war were divided into three categories: some, who were lucky, were riding away; others, frostbitten and maimed, were put into hospitals; and the third category was buried in frozen Finnish soil. But it turned out that there was also a fourth category of unfortunate people, those who waited investigation and trial in that mobile cold wooden prison. Who decides the fate of people in war and sorts them into categories with an unpitying hand? And how easy was the transition from one category to another. Which was determined and which accidental?

One of the peculiarities of this war was the fact that we fought because we were ordered. This was different from the following Patriotic War, when we hated the enemy that attacked our native land. Here they simply told us: "Forward march!" - without even an explanation of where we were going. We simply did our soldier's duty during the Finnish war, and understood the sense and the necessity of the fight later. We didn't feel hate toward Finns initially, and only later, seeing separate cases of atrocities from the enemy, our soldiers started to feel anger toward them. For example, they killed "cuckoos", who caused us a lot of harm, with frenzy. But in general, a Russian, Soviet soldier is a good natured man, and you have to put a lot of effort into angering him.

My tale of the Polish-Finnish epic is coming to an end. I was demobilized in the autumn of 1945, after the Patriotic war also ended. Some lively girl was filling out my military ticket in the Bauman District Military Commissariat. She entered all my misadventures in military service there. "Please put down that I also participated in the war with White Finns." "We don't write the Finnish war," - the girl said and, bending over the desk, yelled to her neighbor: "Svetka, are you going to lunch?" That was the epilogue. Really, why would you "write the Finnish war", when the situation had changed, and you had to forget about that war as soon as possible, pretending that it couldn't even happen with such nice neighbors like Finns.

These memoirs were written by the author mostly when he was in the hospital with pneumonia, in October of 1981. They helped him to fill tedious evenings and sleepless nights of gloomy hospital existence. In the following years, the author simply corrected, extended, and edited these notes.

| Translated

by: Oleg Sheremet Photos from the archive of M. Lukinov |

|

|

|

|