|

Steven H. Parrish; Goldleaf Signs

Copyright 1982. Signs of the Times magazine

From Signs of the Times magazine; April, 1982 issue,

pp 58

by Lynn B. Blaine

Steven Parrish holds a sign

sandblasted for him as a surprise by Mike Jackson,

who first told ST of Parrish's work. The sign

awaits the goldleaf master's touch.

Steven Parrish holds a sign

sandblasted for him as a surprise by Mike Jackson,

who first told ST of Parrish's work. The sign

awaits the goldleaf master's touch. |

|

"Do you still work full-time?" I asked Steven Parrish,

a 72-yr. old goldleaf signman whose work covers Wyoming,

Nebraska, Oklahoma, Texas and Iowa. (Oh, how I fall

into those questions you wish you had never asked.)

"Oh, sure, I even work full-overtime. When I hear somebody

say something about looking forward to retirement, I

think, 'Oh, Lord, here goes another one down the drain,

ready for the undertaker.' Maybe I'm crazy, or it might

be that I'm just too foolish to know any better, but

I just go right on working, rowing my boat and being

independent.

|

"I remember back when I was about 14 or 15, I met an old signpainter

who had snapped signs all over the world. He was snapping some

signs in my hometown, Sandusky, MI, and told me he was 78 years

old. The next time I saw him I was probably somewhere in my

30's, and he said he was 'only 68' - and you couldn't tell the

difference one way or the other, because he hadn't changed.

A fellow like that gives you something to look up to."

Parrish started painting signs before most could learn how

to read - at age five - although those first seven years in

the trade he admittedly held amateur status. Translated, he

didn't get paid. It was not until he was 12 (almost a teenager!)

before he actually charged for his work. Then, in 1921 or

1922, his school needed a scoreboard, so for the "princely

sum" of $8, Parrish set to work on a 4 x 8-ft. sign. His reputation

established, two years later he was asked to goldleaf the

door of the county treasurer's office, which had been destroyed

during a robbery. He had never done goldleaf work before,

and for this particular job he had to match a difficult Brewster

green, put in some red and gold stripping, and do some gold

lettering with a shade. Nevertheless, he did the job, and

then another, because by the time he graduated from high school,

he was earning what he reports was twice as much money as

the average married man. Of course, it's doubtful if the "average

working man" had what Parrish could claim in those days, all

those years of experience under his belt in a skilled profession.

| Parrish doesn't

remember how many hours he was working at signpainting

during high school. He did a lot of work for the school

itself. In his words, "they stopped the clock" for him,

giving him as much time as he needed to complete a project.

The teacher gave him the last 45 minutes of every day

to do as he pleased - sketching, getting ideas, designing. |

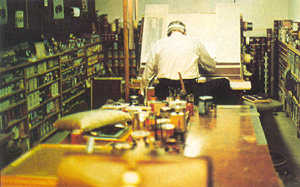

Proof of an organized man: an

organized shop.

|

|

Parish grew up in Michigan, where strikes in the auto industry

took their toll on the business environment and the moisture

in the air took its toll on goldleaf. He recalls complaining

to his wife back in 1949 that if there weren't any better climate

in the U.S. than Michigan's, he would get a two-dollar pistol

and shoot himself. Thirty days later they found themselves alive

and well in Texas, where, he reports, the weather was better

than the market. So he set up shop in Nebraska a year later,

finding it easier to create his own market there. He has been

in Nebraska ever since, the colder but drier air providing a

better atmosphere for the leaf he applies so well.

Since most goldleaf is wet-gilded (put on with a water and

gelatin size), the gold will loosen if water gets to it. Moisture

from the air condensing on windows can work its way throught

the porosity of the glass, giving goldleaf a much shorter

life span. (In those e years, putting varnish on first was

not a common practice.) In Nebraska, and its neighboring states,

Parrish finds that it is not unusual for his work to last

for 30 years.

Examples of back-to-back, vertically

screenprinted patterns, with 23K hand-embossed gold.

|

|

When Parrish moved to Nebraska, he found

people who appreciated goldleaf. He isn't sure why, but

he noticed that there were certain landmarks that would

help him establish his business in much the same way that

hobos' marks serve as a hobo newspaper, indicating likely

places for a handout. Parrish found that "an old boy"

by the name of H.A. Liberty, who did very fine work, had

been a trailblazer: In towns where Parrish found examples

of Liberty's work, he also found it easier to build his

own market. |

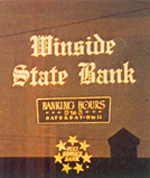

| How did he do it? He recalls

that when he was 13, a client advised him, "When you go

out on the road to make money, make sure to do business

with the people who have it." When Parrish started out,

he found that bankers were the ones who had it, so he

went after bank business and found that the approach worked

very well. He does almost all of his work for banks these

days. |

The outter rim over the farm scene

is pale gold. |

|

He made a miniature sample case with plate glass samples

carried in felt, showing different styles and kinds of goldleaf.

Taking pictures of his work with him as well, he just walked

into banks, and he came back out, on the average, with a contract

from one out of three banks he called on. He has been doing

almost nothing except goldleaf for the last 30 years.

"If you're going to be spreading your efforts in different

directions all the time, you don't get as much accomplished.

You're much better off to specialize on one thing and let

somebody else do the other work," is his advice.

The work of H. A. Liberty, who

opened the way for Parrish 60 years ago. |

|

For Parrish, doing it right

means using japan gold size, made out if tree gun from

China melted down with turpentine. This he puts on with

a fine squirrel-hair brush. For his pictorial work, he

finds the best approach is to use his own process of vertical

screen printing for the pattern. He blows up his design

to a size somewhat larger than he intends to paint it,

smoothes out the edges and makes the details sharp, photographically

reduces it back to proper size, and screens the design

on the glass.

|

Doing it right also means taking the time to do a back-to-back

sign carefully, putting on a panel and applying two coats of

23K gold so that no light comes through and the sign can be

read from both sides. "If all you worry about is hurrying up

to get the sign collectible, you had better forget it," he admonishes.

Competition? Parrish doesn't claim to have much - or any

at all. He reports, with a chuckle, that all the competition

has died off. Sure, there are plenty of "upstarts," but only

one or two who will take the time to "do it right." And he

should know: He ends up repairing the work that wasn't done

properly to begin with. When asked how he gets his business,

he replies, again with a chuckle, that if people haven't heard

of him in his environs, then they just haven't been there

very long, that's all.

| Parrish claims that he doesn't

know how he would have stayed in business if his sixth

sense hadn't told him to stock up on good japan size when

the opportunity struck. He prefers a certain varnish he

had purchased made by Commonwealth, which was sold out

in the 1960's. After it was sold, he found that the two

cases of varnish he had purchased were not the same material.

"It wasn't fuel oil, and it wasn't crude oil, and it wasn't

varnish or anything that resembled it," he claims. |

23K matte gold, hand embossed

on verticallly screenprinted patterns. "Aurora Jewelry"

has back shade; mdiamond shape behind black. "Aurora"

is 16K pale gold. |

|

"It had a sediment at the bottom and smelled horrible, and when

I tried to brush it, it wouldn't dry, so I threw the two cases

out in the garbage. Later he heard through the grapevine that

Dick Blick still had some of the old product they didn't know

they had, so Parrish packed his bags immediately and got in

the car top drive the 700 miles to scrounge up two more cases

"before anybody else could get to it." He has been using the

same two cases ever since, having found that he could thin it

down with more pure gum turpentine when the varnish starts to

thicken as the can is emptied.

He tells a similar story about some red sable brushes he

acquired on the advice of a signpainter who happened to mention

that he had bought some "darned good brushes" form a particular

supplier. Again, Parrish jumped in his car and latched onto

a bunch of red sable brushes. By 1950 the price of those brushes

had gone up to $80 - and he still has some of them.

How long did it take Parrish to master his craft? "Well,"

he says, "I'm still learning. You never stop learning in my

business: It's a matter of speed rather than years. In one

way you're on a par with the fellow who just started yesterday,

except for the fact that you have a little more knowledge

to begin with. It is still a tough job to do. It probably

took me about 20 years to get to the point where I was on

top of it, doing as much as the market would allow."

|

|

Parrish does all

of his own designing. He will incorporate logos, but otherwise

does not deviate from his own designs. His point is that

he tells his what he will do and what the quality will

be. And then it is up to him to deliver. And he is pleased

to tell about his sign that have lasted for 20 or 30 years

without even being revarnished. |

He is entirely self-taught, although he has studied whatever

books he came across (That were any good) down to the last detail.

He has always liked lettering more that other aspects of signpainting,

and his feeling is that, with 6,000 to 7,000 alphabets available

to anybody who wants to dig them out, there will be one that

will be appropriate for each particular job. "The further you

go," he advises, "the more you appreciate the value of these

things, and that's why you have to integrate the idea and make

it mean something. In other words, to just put up a row of letters

doesn't mean anything; that doesn't make a sign. A sign has

characteristics to it that really make it sell, make it carry

out the theme that is intended. It's a means of conveying an

idea so that the next time a fellow who sees it will get the

same idea out of it." And as far as talent goes, he adds, "It's

how much artistry you have in your soul: If you can see it in

your mind's eye, you can carry it out."

Experience teaches things like how to consider the exposure

a sign gets, since the amount of light and the height of the

sign will determine what sort of gold top use. Parrish lets

the deeper gold predominate in the heavy end of the lettering,

doing the ornamentation in pale or lemon gold.

| One technique he doesn't have much call

for now, but which he likes, is using a matte center with

a varnished outline, for which he lays on 23K gold with

a wet size, lets it dry, burnished it, and banks up the

outline 1/16 or ¼ inch. Then on the inside of the letter

he applies japan gold size, gilds and embosses the varnish.

When it is dry, he goes over it with a wet gild and lays

the gold into the size, giving the appearance of having

been chiseled out. "It used to be," he says, "that if

you were going to do an embossing job, you had to use

white damar varnish and in a matter of seconds take an

embossing stick and kind of gouge out the stuff." |

|

|

|

He doesn't have much call for it now because

of the price, although he used to do it frequently. He

recently recommended to one bank that, instead of trying

to change such a sign to incorporate a new name change,

they should take out the |

| plate glass, cut it down, and mount the piece on a pedestal

in the lobby. (Replacing such a sign today costs around

$3,000.) |

What are the differences between "then" and "now" for a

goldleaf specialist? The market conditions, for one thing.

It usually takes a burgeoning economy to support goldleaf,

and goldleaf also takes a bit of selling, Parrish reports,

but he finds it easier to sell goldleaf today. Although inflation

has driven the price of gold up considerably (the pack of

gold that now costs Parrish from $300 top $800 used to cost

him $6.75 - yes, that's right: $6.75 - when he started, back

in the days of the gold standard) price doesn't seem to be

the stumbling block that it used to be and hasn't been since

the price of gasoline started shooting up. He finds that his

customers will spend "almost anything," because they feel

that their money isn't worth the 3 A's: "anything," "anymore,"

"anyway." Customers are willing to go first class if they

see work that is well designed, well executed and gives the

image that they want. His business is as much human nature

as anything else.

Inflation and the rising price of gold have made some changes

in the amount of gold Parrish keeps in stock. At today's going

rate, he doesn't keep much extra around. Whereas he used to

keep about 10 too 12 packs, now his safety deposit box has

five or six in it. He stocks every color of gold, always carrying

a pack of white (12K, half silver and half gold), pale gold

(16K), lemon gold (181/2K), and surface, glass and patent

gold (all 23K).

| He uses the surface gold when

he wants gold to be completely opaque in two applications

for a double-sided sign. Glass gold is the thinnest and

is used for the finest finish. Patent is for guiding in

the wind; it is attached to paper similar to hamburger

wrap and is pressed directly onto the size.

|

|

Parrish finds little calls for silver leaf and basically hasn't

done any of it since the 1950's. The one admonition he has for

silver leafing is not to use varnish, which will hasten the

tarnishing process. He prefers to use white gold (12K) for its

greater warmth.

|

|

The signs Parrish produces give

the same impression that his shop gives: carefully organized,

carefully laid out, everything tidy and right were he

needs it. Although he politely claims to have disarrayed

desktops and need of endless shelves to put his clutter

on, the neatly stacked cans arranged around his workspace,

the rules hanging in graduated lengths by his table, the

recordings that arrive from him, neatly taped shut with

tabs for removing the tape al bespeak an organization

ands attention to detail that is echoed in the care he

takes in his work.

|

Parrish takes pride in performing his craft well, marketing

it straightforwardly and valuing and evaluating the quality

of his own work so well that his customers will also. As he

says himself, his work's quality and his knowledge of his craft

sell his signs. He is in the enjoyable position if knowing that

quality, not price, is his sales tool. He not infrequently has

had his signs encased in weather-proof glass cases, factory

sealed with mitered edges, where his goldleaf will last for

many decades and is likely to be viewed as what it is - a piece

of art, carefully executed down to fine details, which also

happens to be a sign.

Parrish on Pricing

With all the tax money being milked from you-know-who

for the purposes of education, ignorance seems to be holding

its own and making better headway than ever. I often wonder

if in our trade many good artisans, being caught between

a rapidly disappearing apprentice system and as increasingly

expensive educational system, have been compelled to miss

the advantages of both systems and walk a narrow road

to making a living.

My recollections do not call to mind an apologetic

attitudes among signmen of 40 or 50 years ago. They

knew the business, for the most part, and were not ashamed

of it. But this hang-dog whimpering about prices ("you

may get it there, but you can't get it here") seems

to me to be becoming a more vicious evil than the fabled

drunks of yesteryear.

This fawning, slavering, unnecessary explanation of

why they don't charge more for their work has just about

convinced me that they know the price of everything

and the value of nothing. Cost studies concerning goldleaf

work are a field day for the apologists who couldn't

tell you to save their soul why their work is priced

at $.35 or $.45 or $.60 an upright inch. There is room

here for some realistic upgrading of what passes fore

thinking. Who said you should charge such ridiculously

low prices, unless, of course, you don't know what you

are doing? And on that basis you cannot afford to find

out any more than you know now.

I have on many occasions demonstrated to signmen who

said, "I wouldn't dare quote prices like that," that

price has little if anything to do with it. This can

be done easily by asking him to introduce you to the

customer, nothing more. In 15 minutes I will find out

want he wants, and he will find out what it is worth

to do it. I've never lost a customer worth having because

of price. Now, of course, you will tell me, "Well, you

have a special pitch that works>" I do not. I just talk

to a man at his own level, respectfully and in terms

he can understand, and try to answer all his questions

in a simple, straightforward manner.

I had neither the opportunity to apprentice to a sign

shop nor the dubious advantage of an educational (so

I wouldn't have to work for a living, riding the sheepskin

trail to certain success), but I haven't missed the

opportunity to learn all I could about my own business.

When you do this year after year, it will become impossible

to conceal that fact from the customer. He'll be led

to the conclusion that you know what you are doing,

and this in itself, by way of contrast and novelty on

today's market, will make the price issue superficial

and worthless. Value is determined not by what you pay,

but by what you get for what you pay.

It seems to me that too many of us have a tendency

to underrate the value of what we have to offer, with

the exception of a small minority of egotistical novices

who squash an inferiority complex with a bravado which

embraces neither knowledge nor wisdom. As Everett Kay

White always said of this kind, "He talks a good sign.

I wonder how he paints one."

I have observed for many years two reliable gauges

concerning prices. The first is this: If nobody screams

about the price, it is probably too low. If everybody

screams about it, it may be a little high, but if you

know your business, don't flinch an inch. I heard a

seasoned old signman say once, "if you know what you

are doing, the price isn't too high; but if you don't

know what you are doing, you had better take it a little

easy."

My father taught me when I was small to memorize this:

Knowledge is the stuff that wins.

The man without it soon begins

To get his trade in kinks.

No matter where a fellow goes

He's valued for the things he knows

And not the things he thinks.

Respectfully,

(signed) Steven A. Parrish

|

|