|

|

Travel

Literature |

|

Travel

literature is a popular genre of published work today. However, it is

rarely a dispassionate and scientific recording of conditions in other

lands. As a literary genre, it has certain conventions. Readers are generally

seeking the exotic, the other, the different in the places they explore

in literary mode. We want to learn about the headhunters of Borneo, not

the oil rig workers; the wildebeest and gazelles of Africa, not the various

species of rats; the temples of Greece, not the takeaway hamburger restaurants.

We would rather see the inhabitants of a Swiss mountain village dressed

in anachronistic clothes that they wear for an annual culture festival

than in their jeans and T-shirts. We may also be seeking our own origins

and trying to tie our culture and customs to a sense of place. Australians

and Americans lap up literary tours of the historic monuments of England

and Europe. We mostly are not terribly interested in their football teams

or descriptions of the London Stock Exchange. We demand disjunctions of

time, place and continuity, not accuracy. |

|

Medieval

writing about travel and foreign places also had its conventions. Like

so much literature in the middle ages, it drew much from its own inbuilt

literary culture, which included embellishing the plain observations of

travellers with material which had been handed down through chains of

copying from Classical authors or oral tradition. Factual accounts could

be larded with fiction and fantasy drawn from oral tradition or other

literary sources. As with other genres, material from earlier authors

was borrowed, reorganised, reassembled and presented anew. |

|

Strange

creatures, like one legged anthropomorphs who could use their single large

foot as a parasol, escaped from Classical literature of the exotic and

into the writings, visual arts and psyches of medieval people. |

|

|

It

is sometimes asserted that medieval people did not get about much. It

is undoubtedly true that a great many people, possible most ordinary rural

or town dwellers, may have been born, lived and died in the same place.

However, there were groups of people who did travel, and given the conditions

of the time, they travelled most adventurously and sometimes very far.

Soldiers went across the country or to the exotic eastern Mediterranean.

Traders from the Vikings to the merchant adventurers of the later middle

ages voyaged to many exotic ports. Pilgrims undertook journeys to the

nearest popular shrine, or headed off to Compostella or the Holy Land.

Bishops went to Rome and papal emissaries went out to check out the remote

corners of Christendom. Missionaries inserted themselves into potentially

hostile parts of Europe in the early middle ages, and later practitioners

ended up travelling as far as China. The craftsmen who worked on the great

Romanesque and Gothic buildings were an international travelling elite.

The marriages of royalty tended to be diplomatic affairs between competing

aristocrats in different countries, so that courtiers, servants and followers

of the medieval glitterati moved from country to country. The world was

a completely different size, depending on who you were and what your job

was. |

|

|

Royal

travel of the 14th century, after a marginal illustration in the Luttrell

Psalter. |

.|

|

Outside

the known world is the unknown, which has always contained marvels. They

seem to inhabit a marginal area just beyond the edge of the known. Peculiar

creatures and bizarre tales from beyond the fringes of the Classical world

were drawn into the literature of the exotic of the middle ages. A work

entitled Marvels of the East survives in

several Latin manuscripts

and one bilingual Latin/English work, collecting together many of these

oddities. Strange things lived in the east because to the west, once you

got past Ireland, there was only water. Probably a few Irish and Scandinavian

adventurers knew better. |

|

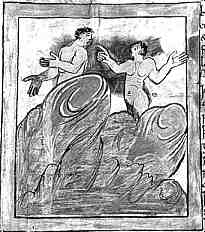

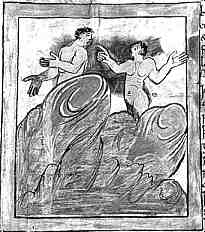

An

illumination from an 11th century copy of Marvels

of the East (British Library, Cotton Tiberius B V). These two naked

figures are not as peculiar as some, except that one of them is supposed

to be dead. By permission of the British Library. |

|

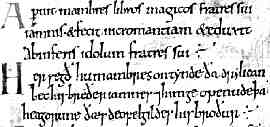

| A

sample of the bilingual text from the above example. By permission of the

British Library. |

|

These

characters from the fringes could be recruited to enhance any travellers'

tales that were beginning to suffer from tedium. It is fascinating to

discover that some of the stock characters, including people with tails

or cannibals who devoured their young, are part of what one might call

ethnic slander across continents and centuries. Earnest Dutch colonial

officers in pith helmets solemnly, if not credulously, recorded these

very stories in 19th century Borneo, told by native peoples against their

enemies who always lived just that bit further up the river. The supernatural

freaks of medieval art and literature may have had their origins in ethnic

lies told by groups at the edge of the then known world. |

|

|

|

While

literacy was strongly tied to the Christian church, particularly in the

earlier part of the middle ages, the literature of travel was not a doctrinally

significant text which must be copied meticulously and without error.

The transmission of some of this material is more akin to what happens

in oral culture, and in many cases was derived from it. Alteration of

a text to produce a good story, or reworking texts to mingle fact and

fiction, was no doubt a legitimate tool of trade of the oral storyteller.

It also appears in the written literature of travel, not as a corruption,

but as part of the art. |

|

It

is worth pondering what is missing from medieval travel literature, because

literate culture was confined to particular social classes. If artisans

had scribbled out their travel diaries with such titles as A Stone

Carver's Tour of Europe then art historians and archaeologists would

not have had so much to do. But they didn't, and so those who speculate

on the organisation of medieval building and craftsmanship and the spread

of influences must rely on close examinations of the works themselves,

the writings of scholars on theoretical matters which might have some

bearing, and such mundane documents as building accounts. |

|

|

Much

academic ink has been expended on analysis of the program of carving at

Chartres Cathedral. |

|

A

certain fascination with the remote and exotic also meant that, to a large

degree, the depiction in writing of the author's own native land was surprisingly

neglected. Chaucer's pilgrims clattered along the road to Canterbury,

but they told yarns rather than noting what they saw along the way. The

writers of chronicles

made occasional observations about the country, but it is not until the

late 15th century when the printer Caxton filleted, compiled and condensed

some of this material into his printed work, The

Description of Britain, that there is some sort of coherent envisagement

of the land. |

|

Caxton |

| After

the Reformation, the drastic effect of the dissolution of the monasteries

and the confiscation of church property led to an interest in the topography

of the country, based on an awareness that the massive remains of a recently

lost past were still standing the landscape. Antiquarians of the 17th, 18th

and 19th centuries created a whole new genre of historical travel literature,

but only after the first heroic attempt to record the rapidly decomposing

splendour of the middle ages was made in the early 16th century by a man

called John Leland, who went mad and died in the attempt. But that is another

story. |

|

The

beautiful monasteries like Rievaulx, tucked into its remote location in

one of the most scenic parts of Yorkshire, only received the attention

of travel writers after they were deserted and ruined. |

|

continued

|

Categories

of Works Categories

of Works |

|

|

|

|

|

|