|

|

|

|

|

|

| Histories of Scripts in the English Royal Chancery |

|

Before the Norman Conquest, the scripts used for royal charters, as well as other formal diplomas, were not different to the insular minuscule used for formal book hands. In the days before Edward the Confessor they were not only written in monasteries, about the only place where sufficiently literate people were to be found, but their forms were probably devised there using models known to the literate churchmen. Many combine the grand formal Latin of ecclesiastical diplomas with details such as property descriptions in Old English. There probably was no formal body constituting a royal chancery. |

|

|

|

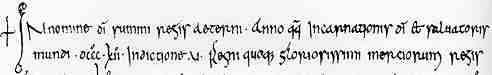

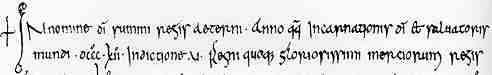

| The first two lines of a charter of King Coenwulf of Mercia from 812 AD. |

|

| |

| Edward the Confessor is credited with the invention of a uniquely English style of charter, referred to as a writ. It was in the Old English vernacular, was brief and to the point, used insular minuscule script and had the double sided great seal appended. There was no tradition in England of the spidery, exaggerated chancery hands derived from New Roman cursive such as were found in the Merovingian and Carolingian chanceries, or in the papal chancery. If Edward had a chancery, it may have consisted only of a few good churchmen recruited for the job. The story is muddied by the knowledge that a good proportion of the writs attributed to Edward the Confessor are known to have been forged. |

|

|

| Seal of Edward the Confessor, as derived from a forged example. |

|

| |

| The Norman Conquest brought invaders who, while they were French speaking, were not steeped in the ancient traditions of the Merovingian and Carolingian chanceries. While William and his Norman knights, descendants of the Vikings, were probably largely illiterate, they brought with them churchmen literate in Latin. William took over the form of the Anglo-Saxon writ for his written proclamations, but it was produced in Latin and written in the Caroline minuscule script used as book hand in that period. The connection between church and chancery was never severed in England during the middle ages, as the chancellor and other senior officials were drawn from senior churchmen. In the later middle ages, the increasing army of chancery clerks were, if not actually clerics, often drawn from minor orders in the church. |

|

|

Charter of William I of around 1070, with detail of the script below (British Library add. ch. 11205). |

|

|

| The differences between the charter hand above and a standard Caroline minuscule book hand are subtle, but suggestive of future directions: angular capitals, tall angled and somewhat spikily wedged ascenders and descenders and occasional letters related to those of insular minuscule, such as open g and capital F. Some other early charters show even more conventional book hand. |

|

| During the course of the first half of the 12th century, the script used for charters became angular and spiky. While we might refer to it as a protogothic document hand, it is rather different in character to the developing Gothic book hand of the period. While it is possible to see changes in the way that charters and official documents were written, paleographical dating of documents is nowhere near so accurate as some would like to believe. Stylistic changes tended to overlap rather than follow each other in rigid waves. In this period it is also not uncommon to find charters written in more or less standard book hand. As these are often grants for the benefit of monasteries, it is likely that these were written in the monasteries themselves rather than the royal chancery, and were either copies of an original, or were brought into the chancery for ratification with the great seal. |

|

|

|

| Top left hand corner of a notification of Henry I of around 1123 (British Library, Cotton Charter vii. 2.). |

|

| The above example shows some important characteristics of the 12th century chancery hand. Letters are angular; ascenders are tall, those of d, f and s being angled while others, such as b, h and l, have split wedged tops. The letter a has a tall curved ascender, while w is enlarged and consists of two spiky vs overlapping. While the ascenders and descenders of tall letters are longer than is usually found in book hands of the period, they are not as exaggerated in either size or fiddly elaboration as their counterparts in the German or papal chanceries. Also unlike those institutions, the English chancery scribes did not employ twirly abbreviation marks, but used simple angular slashes. The basic letter forms remain essentially those of Caroline minuscule, with the differences being in style. |

|

| While formal documents of this period did not contain a dating clause, they can often be dated fairly accurately through historical detective work. The reign of the king, the identity of beneficiaries and witnesses and the location of where the document was issued can all serve to narrow down the possible date range. Document hands therefore have much more internal dating evidence than book hands, and the way that individual styles intersect through time can be seen. In this period the chancery, no doubt a small body of hard workers, did not have a permanent home and travelled around with the king and his court, lodging in castles and monasteries and leaving bundles of records with some friendly abbot or other for safekeeping. |

|

|

| Top left corner of a charter of King Stephen of 1140 (British Library, Cotton Charter vii, 4). |

|

| The above example is very similar to the previous, but introduces the r which extends below the line with an angled descender. This will evolve into one of the tricky letters of English chancery hand and later cursive scripts. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

History of Scripts History of Scripts |

|

What is Paleography? What is Paleography? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|